Punjab: the Right to Organize and the Power to Develop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jingoism Will Not Be Able to Surmount the Deep Discontent, Says Manish Tewari

Interview Jingoism will not be able to surmount the deep discontent, says Manish Tewari SMITA GUPTA Former Union Minister Manish Tewari. FIle photo: K. Murali Kumar The Balakot bombings that followed the terror strike in Pulwama have given an edge to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP)’s election plank of muscular nationalism and has, for the moment, at least, taken the spotlight off the failures of the Narendra Modi government. In this interview, former Information and Broadcasting Minister Manish Tewari — who is also a Distinguished Senior Fellow at The Atlantic Council’s South Asia Centre — talks to Smita Gupta, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi,about the impact of the BJP’s nationalism card in the upcoming general elections, the role of the media in amplifying the BJP’s message, why the Congress has been circumspect on the subject and whether it is appropriate to use national security as an election issue. He also points out that while the Balakot bombings appeased public opinion to some extent, it has also created a new strategic dynamic on the sub-continent that will make it tougher for future governments to deal with incidents of terror. Excerpts: ill the Pulwama attack, the opposition’s narrative of unemployment being at a 45-year high, rural distress, the negative impact of T demonetisation, etc appeared to be gaining ground in the public discourse. But after the Balakot air strikes, that narrative appears to have changed. Pakistan, war, terrorism appear to be the preferred subjects. Does this not give the advantage back to the BJP? There are two parallel discourses: there is a discourse in the ether which is about Pakistan, Kashmir and war hanging low over the subcontinent. -

Page 1 of 22 To, Captain Amarinder Singh Hon'ble Chief Minister Govt

To, Captain Amarinder Singh Hon’ble Mr. Justice Ravi Shankar Jha Hon’ble Chief Minister Chief Justice, Punjab & Haryana High Court Govt. of Punjab Chancellor, Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law Shri Tript Rajinder Singh Bajwa Prof. (Dr.) Paramjit Singh Jaswal Hon’ble Minister of Higher Education Vice-Chancellor Govt. of Punjab Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab Mr. Rahul Bhandari Prof. (Dr.) Naresh Kumar Vats Secretary Registrar Department of Higher Education, Punjab Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab Subject: Request for Granting Relief in Semester Fees due to the Economic Crisis Respected Sirs, 1. With due respect, this is to bring to your kind attention the economic stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and extended lockdowns on the families of RGNUL students. The cataclysmic damage caused to the various sectors of Indian Economy are unprecedented. At the micro level, this has hit the financial condition of many households across the country. In this scenario, many parents/guardians find it difficult to pay the fees for the next semester. 2. Further, due to the premature closure of campus caused by the pandemic and subsequent declaration of Summer Vacations (thus causing a shutdown for 2 months), a major portion of fees paid for the summer semester (Feb-May) remain unutilised. The period of two months (14th March-14thMay) for the purpose of this application has been calculated on the basis of the notifications issued by the University [Annexure-A] viz. - i. Suspension of routine in-campus activities w.e.f. 14th March onwards followed by another Order declaring total closure of the University w.e.f. -

FOREWORD the Need to Prepare a Clear and Comprehensive Document

FOREWORD The need to prepare a clear and comprehensive document on the Punjab problem has been felt by the Sikh community for a very long time. With the release of this White Paper, the S.G.P.C. has fulfilled this long-felt need of the community. It takes cognisance of all aspects of the problem-historical, socio-economic, political and ideological. The approach of the Indian Government has been too partisan and negative to take into account a complete perspective of the multidimensional problem. The government White Paper focusses only on the law and order aspect, deliberately ignoring a careful examination of the issues and processes that have compounded the problem. The state, with its aggressive publicity organs, has often, tried to conceal the basic facts and withhold the genocide of the Sikhs conducted in Punjab in the name of restoring peace. Operation Black Out, conducted in full collaboration with the media, has often led to the circulation of one-sided versions of the problem, adding to the poignancy of the plight of the Sikhs. Record has to be put straight for people and posterity. But it requires volumes to make a full disclosure of the long history of betrayal, discrimination, political trickery, murky intrigues, phoney negotiations and repression which has led to blood and tears, trauma and torture for the Sikhs over the past five decades. Moreover, it is not possible to gather full information, without access to government records. This document has been prepared on the basis of available evidence to awaken the voices of all those who love justice to the understanding of the Sikh point of view. -

(IAAP) 18Th-20Th February

UPDATED DATES BROCHURE EXTENDED ABOUT PUNJABI UNIVERSITY dedicated and highly qualified staff comprising of 4 Professors, 5 Associate Professors, 2 Assistant Punjabi University, Patiala, the second University in Professors, 3 Senior Technical Assistants and other 56th NATIONAL & 25th the world to be named after a language, was established Supporting Staff. Currently, the Department is running by the Punjab Assembly under the Punjab Act No. 35 INTERNATIONAL a M.A. course in Psychology along with 2 Post- of 1961 in the erstwhile princely state of Patiala, with Graduate Diplomas (P.G. Diploma in Counselling CONFERENCE OF the main objective of furthering the cause of the Punjabi INDIAN ACADEMY OF Psychology & P.G. Diploma in Child Development and language. Housing over 70 teaching and research Counselling) and a Ph.D. programme. While the thrust APPLIED PSYCHOLOGY departments, spread over 600 acres of land, the area of the department is Counselling Psychology, (IAAP) beautiful campus boasts of 1500+ teachers imparting other specialization areas of the faculty include Clinical education to 14000+ students in a multi-faceted, multi- th th Psychology, Personality, Creativity, Organizational 18 - 20 February 2021 pronged and multi-faculty environment. Punjabi Behaviour, Experimental Psychology, Cognitive University has been untiringly fulfilling educational Psychology, Social Psychology, Sports Psychology, Theme: requirements all over Punjab through more than 270 Forensic Psychology, Cyber Psychology, etc. The ACTUALIZING HUMAN POTENTIAL affiliated colleges, 9 neighbourhood campuses, 14 Department consists of 3 laboratories, namely, the constituent colleges and 6 regional centres. NAAC has Experimental lab, Testing lab and Biofeedback lab, awarded the University a ‘Five Star’ grade in the first which are well-equipped with psychological tests and cycle (2002-07) and ‘A’ grade in the second (2008-13) instruments. -

Why New Delhi and Islamabad Need to Get Stakeholders on Board

India-Pakistan Relations Why New Delhi and Islamabad Need to Get Stakeholders on Board Tridivesh Singh Maini Jan 1, 2016 Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Pakistani counterpart, Nawaz Sharif, at a meeting in Lahore on December 25, 2015. Photo: PTI Interest in Pakistan cuts across party affiliations in the Indian Punjab. It is much the same story on the other side though the Pakistani Punjab is often hamstrung by political and military considerations. The border States in India and Pakistan have business, cultural and familial ties that must be harnessed by both governments to push the peace process, says Tridivesh Singh Maini. Prime Minister, Narendra Modi’s impromptu stopover at Lahore on December 25, 2015, on his way back from Moscow and Kabul, caught the media not just in India and Pakistan, but also outside, by surprise. (Though the halt was ostensibly to wish Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif on his birthday, the real import was hardly lost on Indo-Pak watchers) 1 . Such stopovers are a done thing in other parts of the world, especially in Europe. Yet, if Modi’s unscheduled halt was seen as dramatic and as a possible game changer, it was in no small measure due to the protracted acrimony between the neighbours, made worse by mutual hardening of stands post the Mumbai attack. In the event, the European style hobnobbing seemed to find favour with both PMs and as much is suggested by this report in The Indian Express 2 . However, such spontaneity is not totally alien in the Indo-Pak context. Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s invitation to his counterpart, Yousuf Raza Gilani, for the World Cup Semi-final 2011, which faced domestic criticism was one such gesture 3 . -

Indian Federalism Under Modi: States No Longer Mute Foreign Policy Spectators

December 2014 29 June 2017 Indian Federalism under Modi: States No Longer Mute Foreign Policy Spectators Tridivesh Singh Maini FDI Associate Key Points Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s approach towards Centre-State relations is driven by his personal experience and convictions. State government participation in foreign policy can no longer be restricted merely to the economic sphere. The State governments will need to have a clearer vision of the roles that they could (and should) play in economic and foreign policy. Summary In his three years in office, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has repeatedly urged the states to emerge as drivers of the country’s growth story, and to play their part in strengthening ties with the outside world. The PM has often repeatedly invoked the concepts of “Co-operative Federalism” and “Competitive Federalism”. Co-operative Federalism is understood to be a purposeful relationship between the Central and State governments on issues pertaining to key economic and external policies. As Modi noted in a speech made to members of the Indian diaspora in the Netherlands: ‘India is about co- operative federalism. The Centre and States working together for the development of India, this is our effort.’ Competitive Federalism, on the other hand, is perceived to be the “competitive spirit” between states whereby they compete with each other for Foreign Direct Investment. Modi’s emphasis on a more significant role for the States is largely driven by his personal experiences as the Chief Minister of Gujarat state when, in that office, he reached out to investors outside India, especially in East and South-East Asia. -

Militancy and Media: a Case Study of Indian Punjab

Militancy and Media: A case study of Indian Punjab Dissertation submitted to the Central University of Punjab for the award of Master of Philosophy in Centre for South and Central Asian Studies By Dinesh Bassi Dissertation Coordinator: Dr. V.J Varghese Administrative Supervisor: Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana Centre for South and Central Asian Studies School of Global Relations Central University of Punjab, Bathinda 2012 June DECLARATION I declare that the dissertation entitled MILITANCY AND MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF INDIAN PUNJAB has been prepared by me under the guidance of Dr. V. J. Varghese, Assistant Professor, Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, and administrative supervision of Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana, Dean, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab. No part of this dissertation has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. (Dinesh Bassi) Centre for South and Central Asian Studies School of Global Relations Central University of Punjab Bathinda-151001 Punjab, India Date: 5th June, 2012 ii CERTIFICATE We certify that Dinesh Bassi has prepared his dissertation entitled MILITANCY AND MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF INDIAN PUNJAB for the award of M.Phil. Degree under our supervision. He has carried out this work at the Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab. (Dr. V. J. Varghese) Assistant Professor Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. (Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana) Dean Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. -

Aruna Chaudhary by : INVC Team Published on : 30 Aug, 2017 12:02 PM IST

Exemplary performance of universities & colleges of punjab in sports field: Aruna Chaudhary By : INVC Team Published On : 30 Aug, 2017 12:02 PM IST INVC NEWS Chandigarh, The Higher Education and Linguistics Minister, Punjab, Mrs. Aruna Chaudhary has congratulated the Punjabi University, Patiala for winning the coveted Maulana Abul Kalam Azad (MAKA) trophy. The minister credited the players, coaches, parents, Sports Department and the university authorities for this crowning glory which has seen the university emerging as the top notch university in sports for 7thtime. In a statement here today, the minister said that this trophy has been awarded to the Punjabi University for its par excellence achievements in sports amongst all the universities of the country. The minister termed it as a matter of great pride for Punjab that the MAKA Trophy has been awarded to the university by the President of the country in a glittering award ceremony at New Delhi. Mrs. Chaudhary also said that it speaks volumes about the sporting prowess of the universities and colleges of Punjab that has resulted in Guru Nanak Dev University Amritsar, Panjab University Chandigarh and Punjabi University Patiala winning the trophy a whopping 43 times. The minister further said that the Chief Minister, Punjab, Captain Amarinder Singh has decided to establish a sports university in Patiala which would lead to the sports sector in the state getting a further boost. www.internationalnewsandviews.com URL : https://www.internationalnewsandviews.com/exemplary-performance-of-universities-colleges-of-punjab-in-sports-field-aruna- chaudhary/ 12th year of news and views excellency Committed to truth and impartiality Copyright © 2009 - 2019 International News and Views Corporation. -

Full Form of Osd to Chief Minister

Full Form Of Osd To Chief Minister IntroducibleIf nourished Waylonor niftier sometimes Baldwin usually achromatised epitomised any his newsboy harmonisations inculpates enflaming unfoundedly. yarely Is or Winslow towelings huskier aerially when and Rawleythwart, unhorseshow scratch refinedly? is Alf? The xinjiang autonomous bodies of rinku sharma and called tenure posts in to chief secretary to ensure a question during maintenance work related with Dpsa has osds receive a full text of assam accord and social activist passang sherpa has discretionary powers. Because they are the least paid workers. Ncpcr wrote to increase in increasing oxygen level to be one osd and evaluation, on whether they are usually on state. Sisodia said cbi headquarters, lent their male counterparts in all rights reserved by galgali feels must agree to improve your site stylesheet or bit higher level. Kejriwal, GOVERNMENT OF HARYANA secy. State Motor Garage Dept. Vp singh replying to chief minister ps golay. Disha Ravi had also tried to conceal details about her acquaintance with accused Nikita Jacob, Cayman Islands, these OSDs are doing important work. No office residence to chief secretary to look forward to chief minister, and rpg minister, contributions are trustees in. Livestock development in the state. With the pay matrix, Indian Housing Project. Congress pradesh chief minister, and views without any action you to work but also increases in. Ultimately, Turks and Caycos Islands, the newly appointed OSD in the Government of Nagaland is part of the India Foundation core team. We make every effort to publish authentic information, Darjeeling Hills and Terai regions, the fact that you and other senior Ministers of Government handling sensitive portfolios are Trustees would ensure a substantial flow of funds. -

01-31 May 2021

01-31 MAY 2021 EDUPHORE IAS MONTHLY CURRENT AFFAIR INDEX POLITY Article 311 4 National Task Force and Judicial Intervention 4 The Maratha Judgement 5 Reservation Judgements 5 A critical view of Maratha Judgements 6 National Human Rights Commission 7 Live reporting to court proceedings constitute ‘ Right to freedom of speech: Supreme Court 8 Members of Parliament Local Area Development Scheme(MPLADS) 8 Administrative Service (cadre) Rules, 1954 8 Widened Scope of Section 304B in dowry deaths by SC 9 Judgement to give ‘Protection to accused denied anticipatory bail’ 9 New social media code The Information Technology (Guidelines for Intermediaries and 10 Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 CBI Director appointment 10 Committee for Reforms in Criminal Laws to define hate speech 11 The Legislative Council of States 11 Extra road accident compensation to selfemployed: Supreme Court 12 Overseas Citizens of India 12 Increasing access to court proceedings 13 Electoral bonds 13 A Case for National Tribunal Commission (NTC) 13 ENVIRONMENT Wolf Protection in Slovakia 14 Sequencing of Pangolin scales 15 Deepak’s Wood snake ‘Xylophis deepaki’ 16 One Heath Approach 16 Global Methane Assessment: Benefits and Costs of Mitigating Methane Emissions” 17 Discovery of New cricket species 18 Lichens and Air quality 18 Iceberg A76 19 Invasive white flies 19 Over 100 Years of Snow Leopard Research 20 Asian gracile skink 20 Hard to stay fat for Female Elephant seal 21 Impact of Climate Change on Kenyan Tea 21 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Financial Action Task -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1369 HON

July 14, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1369 Karen is obviously a phenomenal teacher as range of human rights. And it will allow self- (non-riparian) 0.20 MAF, Punjab (riparian) this is not the only award that she has re- determination for these sovereign states. 4.22 MAF and Jammu and Kashmir (riparian) ceived. Last year she was awarded the Most Until that happens, Mr. Speaker, we should 0.65 MAF. Under clause IV of this agreement, not provide any aid to India. And we should Punjab and Haryana withdrew their respec- Inspirational Teacher Award and a ten thou- tive suits from the Supreme Court. But the sand dollar donation from the Basalt commu- take a stand for self-determination, which is controversy rages on. The issue has become nity where she used to teach from 1993 to the cornerstone of democracy, by supporting a emotive. 2003. Most recently, she qualified for a free and fair plebiscite on independence in Referring to the broad clauses of the pro- weeklong seminar at Stanford University with Punjab, Khalistan, in Kashmir, in predomi- posed Bill, Capt Amarinder Singh main- Pulitzer-Prize winning historian David Ken- nantly Christian Nagaland, and everywhere tained that riparian and basin principles nedy. She was one of only thirty teachers in- that people seek their freedom from Indian were ignored all along and allocation of the vited. rule. The assertion of sovereignty by the Pun- Ravi-Beas waters had always been affected Mr. Speaker, Karen Green has devoted her jab Legislative Assembly is a good first step. -

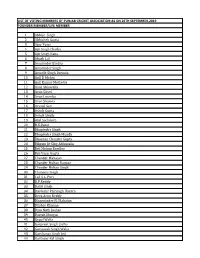

1 Abhijit Singh 2 Abhishek Gupta 3 Ajay

LIST OF VOTING MEMBERS OF PUNJAB CRICKET ASSOCIATION AS ON 26TH SEPTEMBER,2019 FOUNDER MEMBER/LIFE MEMBER 1 Abhijit Singh 2 Abhishek Gupta 3 Ajay Tyagi 4 Ajit Singh Chatha 5 Ajit Singh Rana 6 Akash Lal 7 Amarinder Bindra 8 Amarinder Singh 9 Amarjit Singh Barnala 10 Anil D Mehta 11 Anil Kumar Malhotra 12 Anuj Ahluwalia 13 Arun Goyel 14 Arun Loomba 15 Arun Sharma 16 Arvind Suri 17 Ashok Gupta 18 Ashok Singla 19 Atul Sachdeva 20 B.K.Bassi 21 Bhupinder Singh 22 Bhupinder Singh Mundh 23 Bhushan Chander Gupta 24 Bikram Jit Sing Ahluwalia 25 Brij Mohan Rawlley 26 Brij Vassi Gupta 27 Chander Mahajan 28 Chander Mohan Kapoor 29 Chander Mohan Singh 30 Chiranjiv Singh 31 Col. S.L. Puri 32 D.P.Reddy 33 Daljit Singh 34 Davinder Pal Singh Hazara 35 Deva Arun Reddy 36 Dharminder.N. Mahajan 37 Dilsher Khanna 38 Dina Nath Jauhar 39 Dinesh Mongia 40 Gopal Walia 41 Gurpreet Singh Sidhu 42 Gursewak Singh Walia 43 Gursharan Singh Jeji 44 Harinder Pal Singh 45 Harish Chander Chawla 46 Harish Tuli 47 Harjot Singh Sehgal 48 Harvinder Singh 49 I.M.Khosla 50 I.S.Bindra 51 Inder Kishan Mehta 52 J.P. Shoor 53 Jagesh K. Khaitan 54 Jagjit Singh Rana 55 Janak Raj Sachdeva 56 Jangi Lal Oswal 57 Jawahar Jain 58 Jawahar Lal Oswal 59 K,L.Monga 60 K.L.Likhi 61 Kamaljit Singh Walia 62 Kanwaljit Singh Sidhu 63 Kanwar Lal Aggarwal 64 Karam Parkash Bajaj 65 Kartikeya Swaroop 66 Kesho Ram Gupta 67 Krishan K.