Here Are Four Things to Know About Labor Conditions in the VFX Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Pitch Sessions

Book one-on-one 10 minute pitching sessions and pitch yourself or your project directly to these leading film industry professionals. Sean Cossey - Casting Director - Aikins/Cossey Casting “13 years ago I jumped head first into casting for film & television and haven’t looked back. As did almost every other casting director I know, I started as an assistant, and the rest is history as they say. I’ve had the great fortune of mentoring under one of Canada’s most renowned Casting Directors and feel truly privileged to have him as my partner-in-crime today. Together, we’ve had wonderful experiences… working with incredible Directors the likes of LAWRENCE KASDAN, CHRISTOPHER GUEST, and SCOTT HICKS and also exciting pop-culture phenomena’s such as the TWILIGHT series. Currently I’m working on a number of pilots for the upcoming season, with one to watch out for currently entitled THE WYOMING PROJECT for the CW being developed by Dan & AmySherman Palladino – creators of the GILMOUR GIRLS. And as for the most meaningful reward I get from doing what I do… seeing an actor grow, develop, and achieve their personal best…and all that comes with that.” Tyman Stewart - Talent Agent - The Characters Talent Agency Tyman Stewart has been working in the film industry for Twenty years as a talent agent. He is Senior Vice President and a partner in The Characters Talent Agency (West), and represents many of Canada’s finest actors. His clients can be seen on many Canadian and American television series, and film. Names include Brendan Fletcher, Carly Pope, Daniel Gillies (Spiderman 2 and 3), Amanda Tapping, Michael Shanks, Grace Park, Tyler Labine, Nancy Robertson, Cynthia Stevenson. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Pitchfest Checklist: How to Prepare and What to Bring

Pitchfest Checklist: How to Prepare and What to Bring Jeanne Veillette Bowerman, ScriptMag Editor Pitching anxiety. We all get it. I bet even the pros get a teeny knot in their stomachs. Honestly, I hope to never lose the barb that snags at my insides. It keeps me on my toes. Yes, despite the contacts I have made at studios and production companies, I pitch at a pitchfests. Why? Because it’s a great way to get your foot in the door and make connections with new executives. It’s not about the sale of one idea; it’s about creating a relationship with new producers, submitting polished work that knocks their socks off, and making a great first impression to show them you’re a professional. First step: Be prepared. I don’t care how seasoned you are, there’s prep work involved in presenting your script for a possible sale. Here’s how I prepare for a pitching event as well as what I bring: 1. Travel arrangements: If you haven’t booked a flight yet, plan to stay an extra night. You’ll be exhausted after the event and need time to chill. This way, you can celebrate the success without having to race to the airport. When my schedule allows, I tack on a couple of extra days to take meetings and connect with my existing network who weren’t at the event. If you can get that extra day in L.A., it’ll also give you a chance to take a meeting with one of your old or new contacts, solidifying the connections. -

Pre-Production Guide for GCSE Film Studies

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: WHAT YOU HAVE TO DO 3 WRITING A SCRIPT (500 words.) 4 CREATING A STORYBOARD (20 frames.) 8 PRODUCING A FRONT PAGE AND A CONTENTS PAGE FOR A NEW FILM MAGAZINE 14 PRODUCING A MARKETING CAMPAIGN FOR YOUR FILM (At least 4 items.) 20 HOW WILL YOU DO? 22 GCSE FILM STUDIES GUIDE TO PRE-PRODUCTION PRE-PRODUCTION: (ALMOST) THE FINAL FRONTIER! INTRODUCTION: WHAT YOU HAVE TO DO Ok boys and girls, hereʼs the brief guide to making your pre-production, as promised. As you know, this will need to be finished as a first draft BEFORE you come back to school, along with the pitch. This is all your first shot at this, remember, so while it needs to be complete, you WILL be able to improve upon it before final hand in. Thereʼs lots of advice and pictures to help you along the way with your work in your text book, but hereʼs a few more handy hints and tips for completing the work to help you along the way. First, hereʼs what the exam board wants you to do: ʻSelling an Idea – Pitch and Pre-production (30 marks) These two linked pieces are designed to enable an understanding of the ways in which films are created and sold. Students will have already completed their initial research and analysis focussing on a film that they have chosen, the following two elements of the coursework gives them the chance to explore ideas for their own film. They should work on their own with a specific target audience in mind. -

Baker Scholar Connections 2016

BAKER SCHOLAR CONNECTIONS INTERNATIONAL TRIP I MUMBAI, INDIA 2016 A LETTER FROM OUR PRESIDENT Dear Baker Scholars Alumni, Family, and Friends, For the last time, I write to you as President of the George F. Baker Scholars. My apologies for those of you that have already heard my reflections, but it is something I believe all with association to the Baker Program should hear. Last year at this time, when I found out I had been elected as President, I had three specific goals in mind. First, I wanted the Bakers to become a family – a group of eleven other high-achieving business students that you could come to first for answers to questions, help with personal and professional problems, celebration in success, and support in everyday life. Second, I wanted to plan an international trip that would provide unparal- leled growth opportunities and a lifetime of memories with my Baker family. Finally, our last goal was to recruit top talent for next year’s incoming class and to ensure that the culture we developed in the program this year was not simply a flash in the pan, but a stepping stone to further greatness for the Bakers. I can honestly say that our goal of becoming a Baker family was a complete success. There is no one on campus that I trust more than my fellow Bakers. Regardless of class distinction, everyone banded together with the single focus of making the program the best it could be in every experience we had. I will truly miss working side-by- side with the other Bakers; but, as Katherine Simons/Stritzke (Baker ’08) always reminds us: “Once you’re a Baker, you’re a Baker for life.” That extends to each one of you; you are all a part of the Baker family. -

Coproduction Market Guide

COPRODUCTION MARKET GUIDE MEDIA Antena Catalunya MEDIA Antena Andalucía MEDIA Antena Euskal Herria MEDIA Desk Spain The Coproduction Market Guide has been designed to provide independent European producers and distributors with information related to events and markets around Europe where they can meet potential coproducers, distributors, broadcasters and sales agents. Special thanks to the MEDIA Desk Switzeland MEDIA Antena Catalunya Mestre Nicolau 23, entresól 08021 Barcelona Tel.: 34 93 5524940 / Fax: 34 93 5524953 E-mail: [email protected] www.antenamediacat.eu MEDIA Antena Andalucía C/ Levíes, 17 41004 Sevilla Tel.: 34 95 5037258 / Fax: 34 95 5037265 E-mail: [email protected] www.antenamediaandalucia.com MEDIA Antena Euskal Herria Ramón María Lili 7, 1ºB 20002 San Sebastián Tel.: 34 943 326837 / Fax: 34 943 275415 E-mail: [email protected] www.mediaeusk.eu MEDIA Desk Spain Ciudad de la Imagen Luis Buñuel 2, 2ºA 28223 Pozuelo de Alarcón (Madrid) Tel.: 34 91 5120178 / Fax: 34 91 5120229 E-mail: [email protected] www.mediadeskspain.com European Co-Production Meetings The Co-Production Meetings are designed for bringing together film professionals in order to encourage opportunities for international co-production and to contribute actively to the dynamism of the film industry. These one-to-three-day events, such as Cinemart in Rotterdam, B2B in Belgrade, Producers Network in Cannes, Open Doors in Locarno, CineLink in Sarajevo, Crossroads in Thessaloniki and Baltic Event in Tallinn serve as a meeting platform for a variety of industry professionals from all over the world, people who are looking for high-quality international projects, good business contacts and new initiatives for co-operation with other countries. -

Virtuality Conference Program

Virtuality Conference Turin, November 3-6, 2005 Program THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 3rd morning TORINO INCONTRA CONVENTION CENTRE 8:30 Registration and opening of the XBOX Room, of the Immersive ART Room and of the exhibition stands Cavour Hall 9:00 WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION Gianfranco Balbo Computer Science Department’s Vicerector at the University of Turin and President of the Virtuality Organizing Committee. 10:00 TRIBUTE TO The Moving Picture Company (MPC) With Michael Elson Executive Director of Production at MPC. Moving Picture Company, MPC, is one of the most important studios worldwide concerning animation and digital effects for commercials, television and cinema. MPC created very high profile advertising campaigns for clients like Nike, Levi’s, Stella Artois and Adidas, TV programs for BBC, Channel 4 and Discovery Channel, and it took care of the visual effects for many blockbusters: from Tomb Raider to the Harry Potter series, from Troy to Alien vs Predator, from Batman Begins to the recent Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and the coming Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. During the MPC’s presentation, Michael Elson traces its history, telling it through its most important productions. 11:15 ANIMATION AND VISUAL EFFECTS. SESSION I INVITED TALK The Past, Present and Future of Motion Capture Alberto Menache Digital Effects Supervisor at Sony Pictures Imageworks A motion capture pioneer, Alberto Menache collaborated with most of the test Sony Pictures Imageworks productions, including the recent The Polar Express and the Academy Award nominated Stuart Little2 and Superman Returns. He has worked on many TV commercials and videogames, and he is the author of Understanding Motion Capture for Computer Animation and Video Games, a fundamental text about the use of motion capture in modern animation. -

Official Feature Film Pitch Deck

Official Feature Film Pitch Deck Written & Directed By Alejandro Montoya Marin Love is not like in the movies... right? Synopsis LOW/FI was created with a delicate balance between comedy and drama. It analyzes the life of Lea, a woman in her early 30’s, who has been heavily influenced by pop culture since childhood. After years of mimicking and adhering to advice conveyed through music and film, she is disappointed to find that life isn’t panning out as expected and she is slipping further away from her dreams. Lea then stumbles across the startling realization that she has fallen for the tricks and lies coerced by mainstream society. But everyone knows as adults, being yourself is what is important and it is a lesson that Lea learns throughout the film. Logline: Lea has spent her whole life thinking that love is like movies and tv. After a series of terrible relationships, Lea decides to purge pop culture from her life in an attempt to find real love and the real meaning of her life. Theme: Pop culture gives us unrealistic expectations about the nature of love and life. Tone: The quirkiness of “Scott Pilgrim vs. The World” meets the quarter-life drama of “Garden State.” Director’s Statement LOW/FI is very near and dear to my heart. Although the main character, Lea, is female, I completely identify with her and my intuition tells me that people from all walks of life and from various generations will, as well. Music is a universal art that spikes emotions at any given time. -

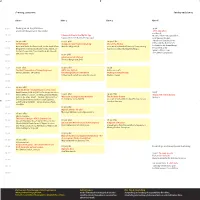

Hauptprogramm2005 21.09.2005 15:07 Uhr Seite 15

Hauptprogramm2005 21.09.2005 15:07 Uhr Seite 15 Sonntag, 9.10.2005 Sunday 10/9/2005 Kino 1 Kino 2 Kino 3 Kino 6 9.00 9.00 9:30 From 9.30 on Registration 9:30 9:30 and Petit Déjeuner in the lobby. eDIT: eDucation im Kino 6. 10:00 Filmproduction in the Digital Age Der Crashkurs für Jugendliche 10:00 Tagesseminar (in German language) und Quereinsteiger: 10:30 10:30 a&t 10:30 p&i 10:30 f&s Arbeit und Karriere in der 10:30 Film- und Medienbranche. AVANTGARDE! Storyboard und Previsualisierung War of the Worlds Eintritt frei bei Anmeldung. Hermann Vaske & Klaus Funk, Studio Funk: Blixa Mareike Hilgenfeldt. presented by Marshall Krasser, Compositing Programm unter 11:00 Bargeld liest Hornbach. Michel Goldschmidt, ar- Supervisor, Industrial Light & Magic. 11:00 www. edit-ves.com. te: Das CD von arte. Tina Kowatsch, Die Manuf- (In German Language) 11:30 aktur: Die adc-Trailer. 11:30 p&i 11:30 Arbeiten mit HD Kamera Thomas Bergmann, DoP. 12:00 12:00 12:30 12:30 c&a 12:30 p&i 12:30 12:30 The Next Generation of Computergames HDTV: der digitale Adobe presents Henry LaBounta, EA Games. kinematographische Workflow Making of Kampfansage 13:00 Volker Kersbaum, Panasonic Broadcast. Steffen Hacker. 13:00 13:30 13:30 14:00 14:00 a&t 14:00 Truth Well Told – Storytelling in Commercials Amir Kassaei, DDB: Golf GTI – Für Jungs, die schon 14:15 14:30 immer Männer waren. Jan Wentz/Fabian Heine, 14:30 p&i 14:30 f&s eDward:Shortfilm Award 14:30 Erste Liebe Film: Smart – Parkuhr. -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

Compositor Objective: to Utilize and Expand My Compositing Expertise

MICHAEL NIKITIN Compositor IMDB: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm2810977/ 1010 President Street #4H Brooklyn NY 11225 Phone: (415) 509-0711 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.udachi.org/compositing.html Objective: To utilize and expand my compositing expertise Software • Expert user of Nuke, Mocha • Proficient in After Effects, Syntheyes, Photoshop Skills • Keying • 2D & 3D tracking • Camera projection • Multipass CG assembly • Particle simulation • DEEP compositing • Stereoscopic techniques March 2016 – present FuseFX (New York, NY) Compositor «American Made» «Luke Cage» «Iron Fist» «Blacklist» «Sneaky Pete» «Notorious» «13 Reasons Why» «The Get Down» «Mr. Robot» • Worked on a wide variety of episodic TV shows and feature films in a fast-turnaround environment utilizing my tracking, keying, match-grading, retiming and, above all, quick thinking skills January 2017 – February 2017 ShadeFX (New York, NY) Compositor «Rough Night» • Worked on several sequences involving 3d tracking, re-projected matte paintings, and a variety of keying techniques December 2015 – March 2016 Mr.X Gotham (New York, NY) Compositor «Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk» • Working on a stereo film project shot at 120FPS. Projections of crowds, flashlights, and particles onto multi-tier geometry, keying, stereo-specific fixes (split-eye color correction, convergence, interactive lighting.) September 2015 – November 2015 Zoic, Inc. (New York, NY) Compositor «Limitless» (TV Show) «Quantico» (TV Show) «Blindspot» (TV Show) • Keying, 2D, palanar, and 3D tracking, camera projections, roto/paint fixes as needed February 2015 – August 2015 Moving Picture Company (Montreal, QC) Compositor «Goosebumps» «Tarzan» «Frankenstein» • Combined and integrated a variety of elements coming from Lighting, Matchmove, Matte Painting and FX departments with live action plates.