An Analysis of Vermont Academy's Internationalization Effort Xiang Wang Mr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

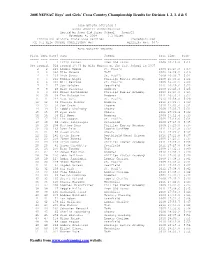

2008 Nepsta Division I

2008 NEPSAC Boys’ and Girls’ Cross Country Championship Results for Division 1, 2, 3, 4 & 5 2008 NEPSTA DIVISION I CROSS-COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS Hosted by Avon Old Farms School Avon,CT November 8, 2008 3.1 Miles Timing By: Granite State Race Services [email protected] .CE 3.1 Mile COURSE CONDITIONS: Wet WEATHER: Wet, 50's =============================================================================== BOYS VARSITY RESULTS =============================================================================== Place TmPl Race# Name School Year Time Pace ===== ==== ===== ======================== ============================== ==== ======= ===== 1 1 1 Tully Hannan Avon Old Farms 2009 16:10.8 5:14 New record. Old record 16:33 by Mike Moreau of The Taft School in 2007 2 2 241 Lowell Reeve St. Paul's 2009 16:27.0 5:19 3 3 263 Mike Moreau Taft 2009 16:28.2 5:19 4 4 233 Nick Gates St. Paul's 2009 16:33.7 5:21 5 5 212 Thomas Leger Phillips Exeter Academy 2009 16:36.2 5:22 6 6 232 Will Ferraro St. Paul's 2009 16:37.2 5:22 7 7 77 Sam Belcher Deerfield 2011 16:39.6 5:23 8 8 29 Mike Discenza Andover 2009 16:45.3 5:25 9 9 219 Miles Richardson Phillips Exeter Academy 2010 16:47.0 5:25 10 10 38 Tim McLaughlin Andover 2011 16:53.4 5:27 11 11 244 Nate Sans St. Paul's 2010 16:58.0 5:29 12 12 32 Charles Ganner Andover 2010 17:01.7 5:30 13 13 54 Sam Craft Choate 2010 17:03.4 5:31 14 14 51 Robbie Cholnoky Choate 2009 17:03.7 5:31 15 15 65 Ryan Rice Choate 2009 17:06.4 5:32 16 16 36 Eli Howe Andover 2009 17:12.4 5:33 17 17 231 Tim Coogan St. -

North Shore Secondary School Fair

NORTH SECONDARY SHORE SCHOOL FAIR The Academy at Penguin Hall Lexington Christian Academy TUESDAY Avon Old Farms School Lincoln Academy TH Belmont Hill School Linden Hall SEPTEMBER 26 Berkshire School Loomis Chaffee School Berwick Academy Marianapolis Preparatory School 6:00-8:30 PM Bishop Fenwick High School Marvelwood School Boston University Academy Middlesex School Brewster Academy Millbrook School FREE & OPEN Brooks School Milton Academy The Cambridge School of Weston Miss Hall’s School TO THE PUBLIC Cate School Miss Porter’s School *Meet representatives CATS Academy New Hampton School Chapel Hill-Chauncy Hall School Noble and Greenough School and gather information Cheshire Academy Northfield Mount Hermon School Choate Rosemary Hall Phillips Academy from day, boarding Christ School Phillips Exeter Academy Clark School Pingree School and parochial schools. Commonwealth School Pomfret School Concord Academy Portsmouth Abbey School Covenant Christian Academy Proctor Academy Cushing Academy The Putney School HOSTED BY: Dana Hall School Saint Mary’s School Deerfield Academy Salisbury School BROOKWOOD SCHOOL Dublin School Shore Country Day School ONE BROOKWOOD ROAD Eaglebrook School Sparhawk School Emma Willard School St. Andrew’s School MANCHESTER, MA 01944 The Ethel Walker School St. George’s School 978-526-4500 Fay School St. John’s Preparatory School brookwood.edu/ssfair The Fessenden School St. Mark’s School Foxcroft Academy St. Mary’s School, Lynn Fryeburg Academy St. Paul’s School Garrison Forest School Stoneleigh-Burnham School -

Vermont Academy of Science and Engineering Directory

Vermont Academy of Science and Engineering Directory Version: 9/25/2009 http://www.uvm.edu/EPSCoR/pdfFiles/Vermont_Academy_of_Science_and_Engineering_Directory.pdf VERMONT ACADEMY OF SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING The Vermont Academy of Science and Engineering (VASE) was founded in 1995 by the Vermont Technology Council, following a recommendation of the Vermont Science and Technology Plan of December, 1994. It was established with three purposes 1. To recognize outstanding achievement and contributions in the broadly defined areas of science and/or engineering 2. To foster a deeper understanding and promote discourse on scientific and technical matters among the citizens of the State of Vermont 3. To provide expert and impartial technical advice to the people and the government of the State of Vermont This “Directory of Members”, first produced in 2006, was revised in subsequent years to add new members, but some information may not be up-to-date. It comprises brief vitae of the members of VASE, outlining their expertise and interests, and providing contact information. Board of Directors of VASE [2009] Christopher Allen President Jeff Finkelstein Past-President Susan Wallace Treasurer, Founding Member Dale Critchlow Founding Member Alan Betts (Past President) Dave Japikse (Past President) General enquiries about VASE should be directed to the President Dr. Christopher Allen: [email protected] http://www.uvm.edu/EPSCoR/pdfFiles/Vermont_Academy_of_Science_and_Engineering_Directory.pdf 1 Table of Contents: Members (Year of election to -

Class AA, Class A, Class B, Class C, Class D, Class E

2020 NEPSAC GIRLS' BASKETBALL TOURNAMENT Class AA, Class A, Class B, Class C, Class D, Class E 2020 NEPSAC Girls' Basketball Tournament Class AA Bracket Wednesday, March 4 Saturday, March 7 Sunday, March 8 Quarterfinals Semifinals Finals 1 # Noble and Greenough Noble and Greenough # 8 # Northfield Mount Hermon # 4 # St. Andrew’s School LIVE St. Andrew’s School 3:00 PM # #5 Bradford Christian Academy # 6:45 PM Rappaport Gymnasium 3 # Worcester Academy Champions Worcester Academy 3:30 PM # 6 # The Rivers School # 2 # Tabor Academy Tabor Academy 4:30 PM # 7 # New Hampton School Contests with a LIVE indicator will be live streamed here: www.bit.ly/NEPSACLIVE 3/8/20 ALL-STAR GAMES IN RICHARDSON GYMNASIUM: CLASS A - 11:00 AM; CLASS B - 12:30 PM; CLASS D/E- 2:00 PM; CLASS C - 3:30 PM 2020 NEPSAC GIRLS' BASKETBALL TOURNAMENT Class AA, Class A, Class B, Class C, Class D, Class E 2020 NEPSAC Girls' Basketball Tournament Class A Bracket Wednesday, March 4 Saturday, March 7 Sunday, March 8 Quarterfinals Semifinals Finals 1 # Marianapolis Preparatory LIVE Marianapolis Preparatory 4:00 PM # 8 # Choate Rosemary Hall # 4 # Deerfield Academy LIVE Deerfield Academy 4:30 PM # 5 # Thayer Academy # 5:00 PM Rappaport Gymnasium 3 # Loomis Chaffee Champions Loomis Chaffee # #6 Buckingham Browne & Nichols # 2 # Tilton School Tilton School # 7 # Phillips Academy Andover Contests with a LIVE indicator will be live streamed here: www.bit.ly/NEPSACLIVE 3/8/20 ALL-STAR GAMES IN RICHARDSON GYMNASIUM: CLASS A - 11:00 AM; CLASS B - 12:30 PM; CLASS D/E- 2:00 PM; CLASS C - 3:30 PM 2020 NEPSAC GIRLS' BASKETBALL TOURNAMENT Class AA, Class A, Class B, Class C, Class D, Class E 2020 NEPSAC Girls' Basketball Tournament Class B Bracket Wednesday, March 4 Saturday, March 7 Sunday, March 8 Quarterfinals Semifinals Finals 1 # Brooks School Brooks School # 8 # Cushing Academy # 4 # Lawrence Academy LIVE Lawrence Academy # 5 # Proctor Academy # 3:15 PM Rappaport Gymnasium 3 # Miss Porter’s School Champions Miss Porter’s School # 6 # Groton School # 2 # St. -

Acceptance List for the Class of 2019 Asheville School, NC Avon Old

Acceptance List for the Class of 2019 Matriculation List for the Class of 2019 Asheville School, NC Avon Old Farms, CT Avon Old Farms School, CT Berkshire School, MA (4) Berkshire School, MA Brewster Academy, NH (2) Blair Academy, NJ Brewster Academy, NH Brooks School, MA Brooks School, MA Canterbury School, CT (3) Canterbury School, CT Choate Rosemary Hall, CT (3) Cate School, CA Cushing Academy, MA Cheshire Academy, CT Dublin School, NH Choate Rosemary Hall, CT Emma Willard, NY Cushing Academy, MA Dublin School, NH Governor’s Academy, MA Emma Willard School, NY Greens Farms Academy, CT Episcopal High School, VA The Gunnery, CT (3) Ethel Walker School, CT Holy Cross High School, CT Foxcroft School, VA Horace Mann School, NY Governor’s Academy, MA Hotchkiss School, CT (3) Groton School, MA The Gunnery, CT Kent School, CT (3) The Hill School, PA Lawrenceville School, NJ Holderness School, NH Loomis Chaffee School, CT (3) Hotchkiss School, CT Millbrook School, NY Hun School of Princeton, NJ Milton Academy, MA Kent School, CT Miss Porter’s School, CT Kimball Union Academy, NH Lawrence Academy, MA New Hampton School, NH Lawrenceville School, NJ Northfield Mt. Hermon School, MA Loomis Chaffee School, CT Peddie School, NJ Mercersburg Academy, PA Phillips Academy, MA Middlesex School, MA Pomfret School, CT Millbrook School, NY Putney School, VT Milton Academy, MA St. Andrew’s School, DE Miss Porter’s School, CT New Hampton School, NH St. George’s School, RI Northfield Mount Hermon, MA St. Mark’s School, MA Peddie School, NJ St. Paul’s School, NH Phillips Academy, Andover, MA Sacred Heart High School, CT Pomfret School, CT Salisbury School, CT (4) Portsmouth Abbey, RI San Domenico School, CA Proctor Academy, NH St. -

District I (51 Chapters)- Rebecca T. Upham, Regent (Rebecca [email protected])

District I (51 Chapters)- Rebecca T. Upham, Regent ([email protected]) Massachusetts Maine Bancroft School Berwick Academy Beaver Country Day School Gould Academy Belmont Hill School Hebron Academy Berkshire School Kents Hill School Brooks School North Yarmouth Academy Buckingham Browne & Nichols Waynflete School Cape Cod Academy Cushing Academy New Hampshire Dana Hall School Holderness School Deerfield Academy Kimball Union Academy Governor’s Academy New Hampton School Lawrence Academy at Groton Phillips Exeter Academy Lincoln-Sudbury Regional HS St. Paul's School MacDuffie School Tilton School Milton Academy Miss Hall's School Rhode Island Newton South High School Moses Brown School Noble and Greenough School Portsmouth Abbey School Northfield Mount Hermon School Providence Classical High School Phillips Academy Providence Country Day School Pingree School St. George's School Rivers School Wheeler School Roxbury Latin School St. Mark’s School Vermont St. Sebastian’s School Vermont Academy Tabor Academy Thayer Academy Walnut Hill School for the Arts Watertown High School Wilbraham and Monson Academy Williston Northampton School Worcester Academy District II (42 Chapters)- Darryl J. Ford, Regent ([email protected]) New Jersey Pennsylvania Blair Academy Agnes Irwin School Cherry Hill High School East Ellis School Doane Academy Episcopal Academy Dwight-Englewood Schools Friends' Central School Gill St. Bernard School Friends Select School Hun School of Princeton Germantown Academy Kent Place School Haverford School Lawrenceville -

All Chapters Member Schools

District I (51 Chapters)- Rebecca T. Upham, Regent ([email protected]) Massachusetts Maine Bancroft School Berwick Academy Beaver Country Day School Gould Academy Belmont Hill School Hebron Academy Berkshire School Kents Hill School Brooks School North Yarmouth Academy Buckingham Browne & Nichols Waynflete School Cape Cod Academy Cushing Academy New Hampshire Dana Hall School Holderness School Dexter Southfield School Kimball Union Academy Deerfield Academy New Hampton School Governor’s Academy Phillips Exeter Academy Lawrence Academy at Groton St. Paul's School Lincoln-Sudbury Regional HS Tilton School MacDuffie School Milton Academy Rhode Island Miss Hall's School Moses Brown School Noble and Greenough School Portsmouth Abbey School Northfield Mount Hermon School Providence Classical High School Phillips Academy Providence Country Day School Pingree School St. George's School Rivers School Wheeler School Roxbury Latin School St. Mark’s School Vermont St. Sebastian’s School Vermont Academy Tabor Academy Thayer Academy Walnut Hill School for the Arts Watertown High School Wilbraham and Monson Academy Williston Northampton School Worcester Academy District II (42 Chapters)- Darryl J. Ford, Regent ([email protected]) New Jersey Pennsylvania Blair Academy Agnes Irwin School Cherry Hill High School East Ellis School Doane Academy Episcopal Academy Dwight-Englewood Schools Friends' Central School Gill St. Bernard School Friends Select School Hun School of Princeton Germantown Academy Kent Place School Haverford School Lawrenceville -

Ssatb Member Schools in the United States Arizona

SSATB MEMBER SCHOOLS IN THE UNITED STATES ALABAMA CALIFORNIA Indian Springs School Adda Clevenger Pelham, AL San Francisco, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 4084 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1110 Saint Bernard Preparatory School, Inc. All Saints' Episcopal Day School Cullman, AL Carmel, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 6350 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1209 ARKANSAS Athenian School Danville, CA Subiaco Academy SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1414 Subiaco, AR SSAT Score Recipient Code: 7555 Bay School of San Francisco San Francisco, CA ARIZONA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1500 Fenster School Bentley School Tucson, AZ Lafayette, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 3141 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1585 Orme School Besant Hill School of Happy Valley Mayer, AZ Ojai, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5578 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 3697 Phoenix Country Day School Brandeis Hillel School Paradise Valley, AZ San Francisco, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5767 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1789 Rancho Solano Preparatory School Branson School Glendale, AZ Ross, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 5997 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 4288 Verde Valley School Buckley School Sedona, AZ Sherman Oaks, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 7930 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 1945 Castilleja School Palo Alto, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2152 Cate School Dunn School Carpinteria, CA Los Olivos, CA SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2170 SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2914 Cathedral School for Boys Fairmont Private Schools ‐ Preparatory San Francisco, CA Academy SSAT Score Recipient Code: 2212 Anaheim, CA SSAT Score Recipient -

Harry R. Carroll Award Recipients

Harry R. Carroll Award Recipients Year Name Institution/School State 2019 Ronn Beck Salve Regina University RI 2018 Debra Johns Yale University CT 2017 Bob Bardwell Monson High School MA 2016 Brenda Poznanski Bishop Guertin High School NH 2015 Jacqueline Murphy Saint Michaels College VT 2014 John Mahoney Boston College MA 2014 Brad Poznanski St. Anselm College NH 2013 Jim Montague Boston Latin School MA 2013 Sherri Geller Gann Academy MA 2012 Laura Frey Vermont Academy VT 2011 Sam Smith Stonehill College MA 2010 Kim Johnston University of Mary Washington VA 2009 Helen Burke Montague Moses Brown School RI 2008 Peter E. Caruso Boston College MA 2007 William R. Fitzsimmons Harvard College MA 2006 Joyce Vining Morgan Putney School VT 2005 Steve McGrath Educational Talent Search NH 2004 Terri Kless Community College of Rhode Island RI 2003 Norma Greenberg Wayland High School MA 2002 Donald Healy St. Anselm College NH 2001 Leslie Miles New Canaan High School CT 2000 Kelly Walter Boston University MA 1999 Tina Segalla Grant St Margaret McTernan School CT 1998 Hugh W. Chandler Weston High School MA 1997 Edward M. Gillis University of Miami FL 1996 Theodore F. Tuttle Wheeler School RI 1995 Gail Roycroft Marshfield High School MA 1994 Richard A. Dufresne Kennebunk High School ME 1993 J. Anthony McLaughlin University of Maine- Farmington ME 1992 William S. Neal Elmira College NY 1991 Dana K. Denault Curry College MA 1990 William J. Munsey University of Maine ME 1989 Russell J. Ryan King School CT 1988 Steven C. Munger Worcester Academy MA 1987 Margaret Addis Newton South High School MA 1986 L. -

For Immediate Release Contact: Susan Carpenter Far Hills Country Day School T

PRESS RELEASE: For Immediate Release Contact: Susan Carpenter Far Hills Country Day School T. 908.766.0622 ext. 427 September 16, 2015 Email: [email protected] Far Hills Country Day School to Host Annual Secondary School Fair Far Hills, NJ – Far Hills Country Day School (Far Hills) will be hosting its annual Secondary School Fair on Thursday, September 24, 2015 at 3:45 p.m. This event is free and open to the public and is the largest secondary school fair on the east coast. Nearly 120 secondary schools will be in attendance, representing the finest day and boarding schools in the country. Local NJ day schools: Delbarton School, Gill St. Bernard’s School, Immaculata High School, Kent Place School, Montclair Kimberley Academy, Morristown-Beard School, Oak Knoll School of the Holy Child, Oratory Preparatory School, Pingry School, Princeton Day School, Rutgers Preparatory School, Saint James School, and The Wardlaw-Hartridge School. Local NJ Boarding Schools: Blair Academy, The Hun School, The Lawrenceville School, Peddie School, Pioneer Academy, and Princeton International School of Mathematics & Science. US Boarding Schools: Andrews Osborne Academy, Avon Old Farms School, Baylor School, Berkshire School, Brewster Academy, Buxton School, The Canterbury School, Cate School, Chapel Hill-Chauncy Hall School, Chatham Hall, Cheshire Academy, Choate Rosemary Hall, Christchurch School, Colorado Rocky Mountain School, Concord Academy, Cushing Academy, Darlington School, Darrow School, Deerfield Academy, Dublin School, EF Academy International, -

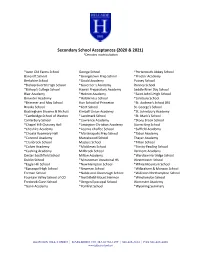

Secondary School Acceptances (2020 & 2021) *Denotes Matricula�On

Secondary School Acceptances (2020 & 2021) *Denotes matriculaon *Avon Old Farms School George School *Portsmouth Abbey School Bancro School *Georgetown Prep School *Proctor Academy Berkshire School *Gould Academy Putney School *Bishop Guern High School *Governor’s Academy Ranney School *Bishop’s College School Hawaii Preparatory Academy Saddle River Day School Blair Academy *Hebron Academy *Saint John’s High School Brewster Academy *Holderness School *Salisbury School *Brimmer and May School Hun School of Princeton *St. Andrew’s School (RI) Brooks School *Kent School St. George’s School Buckingham Browne & Nichols Kimball Union Academy *St. Johnsbury Academy *Cambridge School of Weston *Landmark School *St. Mark’s School Canterbury School *Lawrence Academy *Stony Brook School *Chapel Hill-Chauncy Hall *Lexington Chrisan Academy Storm King School *Cheshire Academy *Loomis Chaffee School *Suffield Academy *Choate Rosemary Hall *Marianapolis Prep School *Tabor Academy *Concord Academy Marvelwood School Thayer Academy *Cranbrook School Masters School *Tilton School *Culver Academy *Middlesex School *Trinity-Pawling School *Cushing Academy Millbrook School Vermont Academy Dexter Southfield School Milton Academy *Wardlaw Hartridge School Dublin School *Minuteman Vocaonal HS Westminster School *Eagle Hill School *New Hampton School *White Mountain School *Episcopal High School *Newman School *Wilbraham & Monson School Forman School *Noble and Greenough School *Williston Northampton School Fountain Valley School of CO *Northfield Mount Hermon *Winchendon School Frederick Gunn School *Oregon Episcopal School Worcester Academy *Gann Academy *Pomfret School *Wyoming Seminary 404 ROBIN HILL STREET | MARLBOROUGH, MA 01752-1099 | 508-485-2824 | FAX 508-485-4420 www.hillsideschool.net . -

2018-2019 Guide to the Secondary School Process

Guide to the Secondary School Process 2018–2019 Table of Contents • Secondary School Counseling Calendar Schedule of events in the secondary school process. • School Visits and Interviews Tips on how to make a favorable impression, common interview questions, examples of questions to ask an admissions officer or tour guide, things to consider following a school visit, and attendance policy for scheduling visits. • Standard Application Online (SAO) & Gateway to Prep Schools Application Resources Information regarding common applications, as well as a list of selected schools that are accepting common applications for the 2018–2019 school year. • Components of Your Son’s Admission File A list of the different parts of the application and who is responsible for each section. • Standardized Testing (SSAT, CSS & TOEFL) Information on each test, how to prepare for the tests, and registration information. • Contact Information Relevant addresses and phone numbers for the Secondary School Counseling Team & for financial aid information. 1 2018 – 2019 Secondary School Counseling Calendar Please follow the instructions that coincide with each date to ensure your son the most productive secondary school process possible. Late April-May Complete and return the Secondary School Counseling Team questionnaire. Your responses to this questionnaire are very valuable as we compile a list of suggested schools for your son. This list will be sent over the summer months and serves as a starting point for the search process. Initial meetings with your son’s secondary school counselor. These meetings will focus on examining your son’s academic performance through the year(s), analysis of the April SSAT score report, discussing interests outside of class, and providing advice on areas for growth in the community and over the summer.