The Mapmaker's Dilemma in Evaluating High-End Inequality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1-3 Front CFP 11-24-10.Indd

Area/State Colby Free Press Wednesday, November 24, 2010 Page 3 Weather Man awaits trial for cocaine Agents give tips Corner From “COCAINE,” Page 1 able any evidence that could help the defendant, cast doubt on prosecution witnesses or might mitigate until a second hearing last Wednesday, where Rodri- punishment. This evidence might include records of for holiday parties guez plead not guilty to one count of possession of threats made by government agents, inconsistent wit- cocaine with intent to distribute. ness statements or prior convictions of witnesses. From “TIPS,” Page 1 several sauces, dips and sea- Rodriguez will stay confi ned until the trial, cur- The prosecution also has to let the defense know soned salts and sugars she had rently set for Tuesday, Jan. 18 with U.S. Senior Dis- of any crimes or acts of the defendant that they in- day meal with a healthy snack made that are more healthy and trict Judge Wesley Brown presiding. A motion hear- tend to use against him at trial. The defendant can or by drinking a big glass of much less expensive than those ing will be held on Friday, Jan. 7, but the defendant object to the use of this evidence up to 14 days be- water. purchased at speciality stores. could change his plea to guilty at any time. fore the trial. Daily discussed healthy tips She demonstrated what size On Tuesday, Brown issued a general order of dis- Once the prosecution has made the evidence avail- on the “good, the bad and the of a pie crust to use depend- covery. -

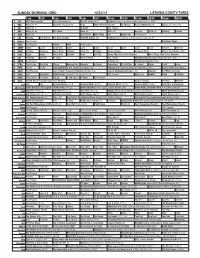

Sunday Morning Grid 12/21/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/21/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Kansas City Chiefs at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Young Men Big Dreams On Money Access Hollywood (N) Skiing U.S. Grand Prix. 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Outback Explore 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Atlanta Falcons at New Orleans Saints. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Christmas Angel 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Alsace-Hubert Heirloom Meals Man in the Kitchen (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Christmas Twister (2012) Casper Van Dien. (PG) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

June COF C1:Customer 5/10/2012 11:01 AM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18JUN 2012 JUN E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG 06 JUNE COF Apparel Shirt Ad:Layout 1 5/10/2012 12:50 PM Page 1 MARVEL HEROES: “SLICES” CHARCOAL T-SHIRT Available only PREORDER NOW! from your local comic shop! GODZILLA: “GOJIRA THE OUTER LIMITS: COMMUNITY: POSTER” BLACK T-SHIRT “THE MAN “INSPECTOR SPACETIME” PREORDER NOW! FROM TOMORROW” LIGHT BLUE T-SHIRT STRIPED T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! PREORDER NOW! COF Gem Page June:gem page v18n1.qxd 5/10/2012 9:39 AM Page 1 THE CREEP #0 MICHAEL AVON OEMING’S DARK HORSE COMICS THE VICTORIES #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BEFORE WATCHMEN: RORSCHACH #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT SUPERMAN: EARTH ONE THE ROCKETEER: VOL. 2 HC CARGO OF DOOM #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT IDW PUBLISHING IT GIRL & THE ATOMICS #1 IMAGE COMICS BLACK KISS II #1 GAMBIT #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 5/10/2012 10:54 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS New Crusaders: Rise of the Heroes #1 G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Wish You Were Here Volume 1 TP/HC G AVATAR PRESS INC Li‘l Homer #1 G BONGO COMICS Steed and Mrs Peel #0 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Pathfinder #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Thun‘da #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Love and Rockets Companion: 30 Years (And Counting) SC G FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Amulet Volume 5: Prince of the Elves GN G GRAPHIX 1 Amelia Rules! Volume 8: Her Permanent Record SC/HC G SIMON & SCHUSTER The Underwater Welder GN G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Archer & Armstrong #1 G VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Tezuka‘s Message to Adolf GN G VERTICAL INC BOOKS & MAGAZINES -

Famous Cartoon Characters and Creators

Famous Cartoon Characters and Creators Sr No. Cartoon Character Creator 1 Archie,Jughead (Archie's Comics) John L. Goldwater, Vic Bloom and Bob Montana 2 Asterix René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo 3 Batman Bob Kane 4 Beavis and Butt-Head Mike Judge 5 Betty Boop Max Flasher 6 Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck and Porky Pig Tex Avery 7 Calvin and Hobbes Bill Watterson 8 Captain Planet and the Planeteers Ted Turner, Robert Larkin III, and Barbara Pyle 9 Casper Seymour Reit and Joe Oriolo 10 Chacha Chaudhary Pran Kumar Sharma 11 Charlie Brown Charles M. Schulz 12 Chip 'n' Dale Bill Justice 13 Chhota Bheem Rajiv Chilaka 14 Chipmunks Ross Bagdasarian 15 Darkwing Duck Tad Stones 16 Dennis the Menace Hank Ketcham 17 Dexter and Dee Dee (Dexter's Laboratory) Genndy Tartakovsky 18 Doraemon Fujiko A. Fujio 19 Ed, Edd 'n' Eddy Danny Antonucci 20 Eric Cartman (South Park) Trey Parker and Matt Stone 21 Family Guy Seth MacFarlane Fantastic Four,Hulk,Iron Man,Spider-Man,Thor,X- 22 Stan Lee Men and Daredevil 23 Fat Albert Bill Cosby,Ken Mundie 24 Garfield James Robert "Jim" Davis 25 Goofy Art Babbitt 26 Hello Kitty Yuko Shimizu 27 Inspector gadget Jean Chalopin, Bruno Bianchi and Andy Heyward 28 Jonny Quest Doug Wildey 29 Johnny Bravo Van Partible 30 Kermit Jim Henson Marvin Martian, Pepé Le Pew, Wile E. Coyote and 31 Chuck Jones Road Runner 32 Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Pluto Walt Disney 33 Mowgli Rudyard Kipling 34 Ninja Hattori-kun Motoo Abiko 35 Phineas and Ferb Dan Povenmire and Jeff “Swampy” Marsh 36 Pinky and The Brain Tom Ruegger 37 Popeye Elsie Segar 38 Pokémon Satoshi Tajiri 39 Ren and Stimpy John Kricfalusi 40 Richie Rich Alfred Harvey and Warren Kremer Page 1 of 2 Sr No. -

Or Live Online Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook and Twitter @Back2past for Updates

5/16 - Golden & Silver Age Comics with Collectible Toys 5/16/2020 This session will be held at 6PM, so join us in the showroom (35045 Plymouth Road, Livonia MI 48150) or live online via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # LOT # 1 Auction Announcements 16 Amazing Spider-Man #175/1977/Early Punisher VF/VF+ condition. 2 Super Natural Thrillers #5/1973/Key Issue 1st appearance of the Living Mummy in VG+/F- 17 Amazing Spider-Man #188/1979/Classic Bronze condition. Sharp VF+ condition. 3 Michelangelo GIANT 50" Big-Fig Figure 18 Star Wars Darth Vader Elite Series 10" Figure Not quite 1:1 scale, but this figure is HUGE! New in Great version of Darth Vader! Exclusive to the Disney original packaging. Some storage wear. Store. New/sealed in box. Minor shelf wear. 4 Amazing Spider-Man #63/1968/Vulture Cover 19 Amazing Spider-Man #190/1979/Key Man-Wolf Classic Silver age in VG+/F- condition. VF/VF+ condition. 5 Amazing Spider-Man #64/1968/Vulture Cover 20 Amazing Spider-Man #193/1979/Key Human Fly Sharp Romita cover in VF condition. 1st appearance in VF condition. 6 Star Wars Darth Vader Legacy Pack 40th Ann 21 Monster High Toy Group (10) New/sealed in box. Very clean with minor shelf wear. All new/sealed in box. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

$ 8 . 9 5 Dr. Strange and Clea TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.71 Apri l 2014 0 3 1 82658 27762 8 Marvel Premiere Marvel • Premiere Marvel Spotlight • Showcase • 1st Issue Special Showcase • & New more! Talent TRYOUTS, ONE-SHOTS, & ONE-HIT WONDERS! Featuring BRUNNER • COLAN • ENGLEHART • PLOOG • TRIMPE COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND COMICS’ BRONZE AGE BEYOND! Volume 1, Number 71 April 2014 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Arthur Adams (art from the collection of David Mandel) COVER COLORIST ONE-HIT WONDERS: The Bat-Squad . .2 Glenn Whitmore Batman’s small band of British helpers were seen in a single Brave and Bold issue COVER DESIGNER ONE-HIT WONDERS: The Crusader . .4 Michael Kronenberg Hopefully you didn’t grow too attached to the guest hero in Aquaman #56 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: Ready for the Marvel Spotlight . .6 Creators galore look back at the series that launched several important concepts SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz David Kirkpatrick FLASHBACK: Marvel Feature . .14 Arthur Adams Todd Klein Mark Arnold David Anthony Kraft Home to the Defenders, Ant-Man, and Thing team-ups Michael Aushenker Paul Kupperberg Frank Balas Paul Levitz FLASHBACK: Marvel Premiere . .19 Chris Brennaman Steve Lightle A round-up of familiar, freaky, and failed features, with numerous creator anecdotes Norm Breyfogle Dave Lillard Eliot R. Brown David Mandel FLASHBACK: Strange Tales . .33 Cary Burkett Kelvin Mao Jarrod Buttery Marvel Comics The disposable heroes and throwaway characters of Marvel’s weirdest tryout book Nick Cardy David Michelinie Dewey Cassell Allen Milgrom BEYOND CAPES: 221B at DC: Sherlock Holmes at DC Comics . -

BATMAN: a HERO UNMASKED Narrative Analysis of a Superhero Tale

BATMAN: A HERO UNMASKED Narrative Analysis of a Superhero Tale BY KELLY A. BERG NELLIS Dr. William Deering, Chairman Dr. Leslie Midkiff-DeBauche Dr. Mark Tolstedt A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN Stevens Point, Wisconsin August 1995 FORMC Report of Thesis Proposal Review Colleen A. Berg Nellis The Advisory Committee has reviewed the thesis proposal of the above named student. It is the committee's recommendation: X A) That the proposal be approved and that the thesis be completed as proposed, subject to the following understandings: B) That the proposal be resubmitted when the following deficiencies have been incorporated into a revision: Advisory Committee: Date: .::!°®E: \ ~jjj_s ~~~~------Advisor ~-.... ~·,i._,__,.\...,,_ .,;,,,,,/-~-v ok. ABSTRACT Comics are an integral aspect of America's development and culture. The comics have chronicled historical milestones, determined fashion and shaped the way society viewed events and issues. They also offered entertainment and escape. The comics were particularly effective in providing heroes for Americans of all ages. One of those heroes -- or more accurately, superheroes -- is the Batman. A crime-fighting, masked avenger, the Batman was one of few comic characters that survived more than a half-century of changes in the country. Unlike his counterpart and rival -- Superman -- the Batman's popularity has been attributed to his embodiment of human qualities. Thus, as a hero, the Batman says something about the culture for which he is an ideal. The character's longevity and the alterations he endured offer a glimpse into the society that invoked the transformations. -

Maternity Leave Policy Removes

* 1932 * The Studeats' Voice for Over 55 YearS * 1988 * ... Vol. 56 No•• Barach.CoIlege, CUNY September 27, 1_ e ort Ro~lysori Baruch Maternity Leave Appointed Institutes Baruch College is being reviewed for accreditation this fall, according Smoking Policy Removes to the Provost's Office.' .. Acting Day Se:ssien StudeRtGovernment Ban President Ainsley Boisson bas been By BOLLY III'ITMAN College Employee electedBarueh representative to the Asso-ciate A smoking policy has been in University Student Senate. stated at Baruch College. The Provost policy, which came into effect as of By DOUG DROHAN The Day' Session Student By-RlI'A LEAHY June 1988, is required by the New Yorlc City Clean Indoor Air Act Government will allot SI02,OOO for Carl Rollyson is the newly ap- andmust be followed by all the City College Office Assistant Jean- there were only two jobs available. I school spending and SI94,OOO for pointed Acting Associate Provost Universities of. New York. This nette Shuck blames ~ 'office pressed the issue as far as the Pro student clubs. for Academic Affairs for the col- detailed and stringent policy has politics" for her removal from the vost's Office in order to maintain lege. many individuals atBarucb talking, Student Activities· Office. Shuck status quo in my department," he stated and added that the final deci Two Lower Council and one Up Chosen in late August, Rollyson smokers and non smokers alike. was transferred to· the Registrar's has previously served as the Assis- Amongst.the many regulations Office because another College sion to place Shuck in the per Council positions are available Registrar's Office was based on on the DSSG. -

Holiday Movies to Stream for FREE!

Holiday Movies to Stream for FREE! CLASSICS ANIMATED Babes in Toyland (1961) (Disney+) An All Dog's Christmas Carol (Amazon Prime) Angela's Christmas (Netflix) A Christmas Carol (1954) (Amazon Prime) Beauty & The Beast Enchanted Christmas (Disney+) A Christmas Carol (2009, Animated) Bob's Broken Sleigh (Netflix) (Disney+) Cat in the Hat Knows A Lot About Christmas (Amazon Prime) Christmas Cartoon Classics (Amazon Christmas Dragon (Amazon Prime) Prime) Christmas Elves (Amazon Prime) Christmas Cartoon Extravaganza (Amazon Prime) Gumby's Christmas Capers (Amazon Crawford the Cat's Christmas (Amazon Prime) Prime) Elf Pets Santa's Reindeer Rescue (Netflix) Home Alone (Disney+) Elliot the Littlest Reindeer (Netflix) Home Alone 2: Lost in New York (Disney+) Emmett Otter's Jug Band Christmas (Amazon Prime) How the Grinch Stole Christmas (Netflix) The Grinch (Netflix) It's a Wonderful Life (Amazon Prime) Happy Holidays from Madagascar (Netflix) Home for the Holidays (Netflix) Mickey's Christmas Carol (Disney+) Klaus (Netflix) Miracle on 34th Street (1947) (Disney+) Magic Gift of the Snowman (Amazon Prime) Muppet Christmas Carol (Disney+) Marvel's Super Hero Adventures: Frost Fight (Netflix) The Santa Clause (Disney+) Mickey's Once Upon a Christmas (Disney+) The Santa Clause 2 (Disney+) Mouse & Mole at Christmas Time (Amazon Prime) My Little Pony Best Gift Ever (Netflix) White Christmas (Netflix) Olaf's Frozen Adventure (Disney+) Pluto's Christmas Tree (Disney+) Santa's Workshop (Disney+) The Small One (Disney+) Have cable? Visit Spirit Riding -

Ron Butler NEW Resume

Ron Butler SAG-AFTRA / AEA TELEVISION (Partial List) GENERAL HOSPITAL Recurring Guest Star ABC SWITCHED AT BIRTH Guest Star ABC SECRETS & LIES Co Star ABC RICHIE RICH Guest Star Awesomeness TV FRIENDS OF THE PEOPLE Guest Star Current TV I DIDN’T DO IT Guest Star Disney – Dir. Joel Zwick IT’S ALWAYS SUNNY IN PHILADELPHIA Guest Star FX – Dir. Richie Keen BUNHEADS Recurring Guest Star ABC - Dir. Elodie Keene GREY’S ANATOMY Co-Star ABC - Dir Ron Underwood PARENTHOOD Co-Star NBC - Dir. Dylan Massin SHAMELESS Co-Star Showtime - Dir. Gary Goldman DOG WITH A BLOG Co-Star Disney - Dir. Neal Israel TORCHWOOD Guest Star BBC - STARZ/Dir. Bharat Nalluri INCREDIBLE CREW Co-Star Cartoon Network - Dir. Danny J. Boyle THREE RIVERS Recurring CBS - Dir. Peter Markle FIRST DAY 2: FIRST DANCE Lead Alloy Entertainment - Dir. Sandy Smolan TRUE JACKSON, VP Series Regular Nickelodeon - Dir. Gary Halverson DIRTY SEXY MONEY Guest Star ABC - Dir. Jeff Mellman JIMMY KIMMEL LIVE Barack Obama (recurring) ABC HOW I MET YOUR MOTHER Co-Star NBC - Dir. Pam Fryer SARAH CONNOR CHRONICLES Co-Star FOX - Dir. Charles Beeson CROSSING JORDAN Recurring NBC - Dir. Donna Deitch INVASION Recurring ABC - Dir. Michael Nankin NURSES (Pilot) Co-Star FOX - Dir. PJ Hogan MEDIUM Co-Star NBC - Dir. Joanna Kerns WITHOUT A TRACE Co-Star CBS - Dir. Jonathan Kaplan FILM TICK TOCK TOO Supporting Dir. Josh Stolberg SMOTHER Supporting Dir. Vince Di Meglio RAIN Supporting with C.C.H. Pounder EVERYDAY PEOPLE Lead HBO Films - Dir. Jim McKay, Sundance SPARTAN Supporting Warner Bros. - Dir. Mamet JEFFREY’S HOLLYWOOD TRICK Supporting Berlin Film Festival ELEANOR Supporting Hamptons Film Festival HOMICIDE Supporting Columbia Tristar / Dir. -

MODERN LETTERS Te P¯U Tahi Tuhi Auaha O Te Ao

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯u tahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 8 December 2006 This is the 99th in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email [email protected] 1. Rugby script wins Embassy Trust Prize............................................................. 1 2. More scripting success......................................................................................... 2 3. Writing workshops (1): Short Fiction................................................................. 2 4. Writing workshops (2): Creative NonFiction.................................................... 2 5. Other lives............................................................................................................ 3 6. The loss of Oz Lit?............................................................................................... 3 7. The next half dozen.............................................................................................. 4 8. ‘Tis the season to be jolly (1) ............................................................................... 4 9. ‘Tis the season to be jolly (2) ............................................................................... 5 10. But wait, there’s more ....................................................................................... 5 11. Last call for Evil Advice!.................................................................................. -

Norman Maurer Papers, 1976-1983 PASC.0086

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c84x5f61 No online items Finding Aid for the Norman Maurer papers, 1976-1983 PASC.0086 Finding aid prepared by Processed by Arts Library Special Collections staff, pre-1999; machine-readable finding aid created by Julie Graham and Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2014 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Norman PASC.0086 1 Maurer papers, 1976-1983 PASC.0086 Title: Norman Maurer papers Identifier/Call Number: PASC.0086 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 18.0 linear feet(43 boxes) Date: 1976-1983 Abstract: Norman Maurer was writer, film director and producer, and also worked for many years in television animation for Hanna Barbera and ABC, writing and editing. The collection consists of scripts, photocopies of storyboards, and outlines for children's animated television programs including, The Adventures of Goldie Gold (1981), Dingbat and the creeps (1980), Fangface (1979), Heathcliff (1979-81), Marmaduke (1981), Mork and Mindy (1980-82), Plastic family (1980-81), Richie Rich (1979-81), Scooby and Scrappy Doo (1980-81), Super friends (1980-81), and Thundarr the barbarian (1979-81). Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. creator: Maurer, Joan Howard creator: Maurer, Norman, 1926-1986 Restrictions on Access STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection.