Ascetic Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2010 By

1 AS INTRODUCED IN LOK SABHA Bill No. 76 of 2010 THE CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2010 By SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ, M.P. A BILL further to amend the Constitution of India. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Sixty-first Year of the Republic of India as follows:— 1. This Act may be called the Constitution (Amendment) Act, 2010. Short title. 2. In the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution,— Amendment of the Eighth (i) entries 5 to 9 shall be renumbered as entries 6 to 10, respectively, and before Schedule. 5 entry 6 as so renumbered, the following entry shall be inserted, namely:— “5. Garhwali.”; (ii) after entry 10 as so renumbered, the following entry shall be inserted, namely:— “11. Kumaoni.”; and 10 (iii) existing entries 10 to 22 shall be renumbered as entries 12 to 24, respectively. STATEMENT OF OBJECTS AND REASONS The Eighth Schedule to the Constitution recognizes twenty-two languages as national languages of India being spoken and written by the citizens. It is believed that education, culture and intellectual pursuits get created and develop around these languages. But it is unfortunate that languages like Garhwali and Kumaoni spoken and written by millions of people having distinct culture have not yet been included in the Eighth Schedule. The Garhwali language is being spoken since ancient times in the Kedarkhand region of Central Himalaya. However, when exactly the people started using this language in writings can be correctly answered by linguistics only. Prior to 13th century, when the Hindi language was not in existence, the official work of the State of Garhwal, spreading from Saharanpur to Himachal, was being done in Garhwali language. -

2 6043/6044 Madras-Patna Express from Weekly to Bi

2 6043/6044 Madras-Patna Express from 9 M/s Tantia Constn . Calcutta. weekly to bi-weekly 10 M/s Kalindee Infrastructure Development (pi 3. 6045/6046 Madras Ahmadabad Navjeevan Ltd., New Delhi Express from 6 days a week to daily, Railway Electrification 4 8301/8302 Hirakud Express from tri weekly 1. M/s Larsen & Toubro Ltd., Madras to 4 days a week. 2. M/s KEC (International) Ltd., Madras. 5 4863/4864 Marudhar Express from tri-weekly to 4 days a week 3 M/s SAE (India) Ltd.. New Delhi. 6. 8403/8404 Purt Ahmedabad Express from 4. M/s SPIC-SMO Ltd.. Madras weekly to tri-weekly Rolling Stock 7 6339/6340 Nagercoil Mumbai CST Express 1 M/s BHEL, Bhopal. from weekly to tri-weekly 2 M/s IDBI. Bombay 8 7003/7004 Howrah Secunderabad Falaknuma Express from tri-weekly to daily. 3. M/s IRCON, New Delhi, (c) and (d) It is proposed to increase the frequency 4. M/s Jagson International, New Delhi of 2421/2422 New Delhi-Bhubaneswar Rajdhani 5. M/s BESCO, Calcutta. Express from weekly to bi-weekijf on availability ot 6. M/s CIMMCo, Calcutta additional Rajdhani rake from Production units 7 M/s Tebma Engg. Ltd., Madras Introduction of BOLT Scheme 8 M/s BEML, Bangalore 9. M/s SRF Finance, New Delhi, 333 DR KRUPASINDHU BHOI : Will the Minister of RAILWAYS be pleased to state Track Machines (a) the date of the introduction of BOLT scheme by 1. M/s Plasser & Theurer, Austria. Railways; 2. M/s. Engineering Prestressed Antri Unit. -

S28 - UTTARANCHAL PC No

General Elections, 1999 Details for Assembly Segments of Parliamentary Constituencies Candidate No & Name Party Votes State-UT Code & Name : S28 - UTTARANCHAL PC No. & Name : 1-Tehri Garhwal AC Number and AC Name 1-Uttarkashi 1 Manabendra Shah BJP 41539 2 Munna Chauhan SP 7463 3 Rajeev Rawat BSP 623 4 Vijay Bahuguna INC 33095 5 Vidya Sagar Nautiyal CPI 3855 6 Darshan Lal Dimiri ABHM 842 7 Bishnu Pal Singh Rawat UKKD 1181 8 Virendra Singh Negi IND 390 Total Valid Votes for the AC : 88988 AC Number and AC Name 2-Tehri 1 Manabendra Shah BJP 34662 2 Munna Chauhan SP 2401 3 Rajeev Rawat BSP 700 4 Vijay Bahuguna INC 31401 5 Vidya Sagar Nautiyal CPI 3697 6 Darshan Lal Dimiri ABHM 715 7 Bishnu Pal Singh Rawat UKKD 314 8 Virendra Singh Negi IND 528 Total Valid Votes for the AC : 74418 AC Number and AC Name 3-Deoprayag 1 Manabendra Shah BJP 35091 2 Munna Chauhan SP 1856 3 Rajeev Rawat BSP 1127 4 Vijay Bahuguna INC 26332 5 Vidya Sagar Nautiyal CPI 3848 6 Darshan Lal Dimiri ABHM 652 7 Bishnu Pal Singh Rawat UKKD 293 8 Virendra Singh Negi IND 597 Total Valid Votes for the AC : 69796 AC Number and AC Name 423-Mussoorie 1 Manabendra Shah BJP 67592 2 Munna Chauhan SP 6103 3 Rajeev Rawat BSP 3281 4 Vijay Bahuguna INC 61752 5 Vidya Sagar Nautiyal CPI 3339 6 Darshan Lal Dimiri ABHM 702 7 Bishnu Pal Singh Rawat UKKD 368 8 Virendra Singh Negi IND 280 Total Valid Votes for the AC : 143417 Election Commission of India - GE-1999 Assembly Segment Details for PCs Page 1 of 11 General Elections, 1999 Details for Assembly Segments of Parliamentary Constituencies -

List of Star Campainer of BJP for 44

0 0 aj[iicpi4), ici'I, tTPT UT, fljITq 'ti's, 'uFlqieiq 'iP*I't, t&ticjW— 248001 qj'pj 0 (0135) - 2713760, 2713551 iø (0135) - 2713724 'H'sqJ: 3'Lj jS' /XXV-40 /2018 Ic&rf: 1'IIcb I' .-tclJ*.(, 2019. Most-Urqent 11e1iftI. , rdl pcjftj'1 &1W5Tt, 44—f?TaflcIflc fliii u'ii 1ici1rii U'T Plcl[t11-2019— i'j) q ulicti tii!T w'cu tci' *Y 41[ q it.ii1ctci ThV1CP 'J- i"jq 'il-Id! qi1, * 'wsql— I.IIC1'? 6 EFR 2019 5:ft f cpfçjL4 'Ei* ti-cuil1ci * * wfrr &-i tRi 1t CP5'1 S Pthi Sntci fb m-tqq aiiii m 44—l'2.iiHk fMN TflT Pkllrl'i aN WI PIc11rl"-I-2019 ul-icil W"fl *eii Mt1I'.cll cf t.!.tl1 t1 cPNIei4 Ru ct "i41 t Rsn1 31lciIci' ti4cii) t Ri iiT T t I am: 3TtT*1b 'acm ct4cn1 cp TT5t cPI (-1*c cfl'(-J 'H511P J Pii1-i artiint, J,A3cxlcfl(IU's I 0 0 NJ -i)ci Ri'ici 1:1kw '311419 k1M4C1 fajiii ulcicll tll& ut. 9697025550 6tftICSJUS R9Th5 — 06.11.2019 tl<SLT Piiimi a1RwI'a, jgz airdt'i jcc1lt1u.s 5'('Vf I — ff*vr (ltiii.tri sgIg —2019) mcfl 'ultil tlT * R Sllkti ft tt * '(1'lkl lkt f4tn (lmii s'1ia —oig) * ii4 1 ii1 * 1T ii'dli *lcll d * w * iii *iev'i R aii* PillQ1 fti " ckr it anti '-&jq Riq, 1;witq c*,iqkiq 39/29/3, qcicili t, @içt (4i11Ivs),31T (0135) 2669578, 2671306, LetH : 26699587 Arun Singh -TPUcTh-I 'l'ic11 iI1 ational General Secretary & Bharatiya Janata Party Incharge, Head Quarter Ref. -

The Chief Minister, Vijay Bahuguna, Attended the 33Rd Indian

Government of Uttarakhand Information and Public Relations Department Media Center secretariat Press Note New Delhi /Dehradun; 25rd Nov,2013 : The Chief Minister, Vijay Bahuguna, attended the 33rd Indian International Trade Fair on the occasion of Uttarakhand Day organised at Pragati Maidan in New Delhi today. A cultural evening was held to mark the occasion. Several artists from Uttarakhand performed at the cultural evening organized at the Lal Chowk Theatre. The audience witnessed the rich and historic culture of Uttarakhand through the performances held today. This event was held by the Industrial Department with the help of the state’s cultural department. During his visit, the CM also went around the Uttarakhand Pavilion at the trade fair and took information about the products on display. At the pavilion, there are 50 stalls of handicraft, 23 of food items and 22 of business stalls in hall number 6. The products of the state have received great appreciation at the international trade fair and thus have done good business. Exhibitors have received several enquiries and orders. This year the attraction of the fair were the mementoes produced by the Uttarakhand Handicraft Department. These have been developed with the help of the Uttarakhand Small & Medium Scale Industries Department along with the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad. NID has made an effort to develop the state’s handicraft industry according to the market demand and turn it into a source of employment. Thus, new designs of candles are being developed in Tamra Shilp at Bageshwar, Ulan and Ringal Shilp at Uttarkashi, Aipan at Almora and Nainital districts. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

1 Wednesday, February 13

As of Feb 12 Wednesday, February 13 0800-1700 Delegate arrival/registration Venue: Ganga Resort 0800-1230 Complimentary Half Day Tour Note: Pick up from Ganga Resort & Drop off: All official Hotels 0800-1230 River Rafting – Shivpuri to Shivanand Jhula (Ram Jhula) – 16 kms Shivpuri is the starting point of the rafting and is located at a stretch of 16 km at Rishikesh – Badrinath highway. Shivpuri sees a lot of tourist activity day-in and day-out courtesy its significance as the most popular starting point. This point serves as the ideal launch-pad for white water rafting. OR 0900-1230 Heritage walk to the Beatles Ashram The walk will start from Shivanand Jhula (Ram Jhula) to Beatles Ashram and back to Shivanand Jhula. Shivanand Jhula (Ram Jhula) is an iron suspension bridge across the river Ganges, this bridge was built in the year 1986 and it is one of the iconic landmarks of Rishikesh. Beatles Ashram also known as Chaurasi Kutia, during 1960s and 1970s as the International Academy of Meditation, it was the training centre for students of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who devised the Transcendental Meditation Technique. The Ashram gained International attention between February and April 1968 when the rock band the Beatles studied Meditation there along with celebrities such as Donovan, Mia Farrow and Mike Love. 1800-1830 Experience Ganga Aarti The Ganga Aarti is one of the most beautiful experiences in India. The spiritually uplifting ceremony is performed daily to honour the River Goddess Ganga. The aarti ritual is of high religious significance. Fire is used as an offering to the river. -

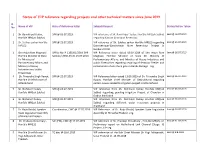

Status of VIP Reference Regarding Projects and Other Technical Matters Since June 2019

Status of VIP reference regarding projects and other technical matters since June 2019 Sl. No Name of VIP Date of Reference letter Subject/Request Status/Action Taken No 1 Sh. Ram Kripal Yadav, SPR @ 03.07.2019 VIP reference of Sh. Ram Kripal Yadav, Hon'ble MP(Lok Sabha) Sent @ 16.07.2019 Hon'ble MP(Lok Sabha) regarding Kadvan (Indrapuri Reservior) 2 Sh. Subhas sarkar Hon'ble SPR @ 23.07.2019 VIP reference of Sh. Subhas sarkar Hon'ble MP(LS) regarding Sent @ 25.07.2019 MP(LS) Dwrakeshwar-Gandheswar River Reserviour Project in Bankura (W.B) 3 Shri Arjun Ram Meghwal SPR Lr.No. P-11019/1/2019-SPR VIP Reference letter dated 09.07.2019 of Shri Arjun Ram Sent @ 26.07.2019 Hon’ble Minister of State Section/ 2900-03 dt. 25.07.2019 Meghwal Hon’ble Minister of State for Ministry of for Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs; and Ministry of Heavy Industries and Parliamentary Affairs; and public Enterprises regarding repairing of ferozpur Feeder and Ministry of Heavy construction of one more gate in Harike Barrage -reg Industries and public Enterprises 4 Sh. Trivendra Singh Rawat, SPR @ 22.07.2019 VIP Reference letter dated 13.06.2019 of Sh. Trivendra Singh Sent @ 26.07.2019 Hon’ble Chief Minister of Rawat, Hon’ble Chief Minister of Uttarakhand regarding Uttarakhand certain issues related to irrigation project in Uttarakhand. 5 Sh. Nishikant Dubey SPR @ 03.07.2019 VIP reference from Sh. Nishikant Dubey Hon'ble MP(Lok Sent @ 26.07.2019 Hon'ble MP(Lok Sabha) Sabha) regarding pending Irrigation Project of Chandan in Godda Jharkhand 6 Sh. -

Induction Material

INDUCTION MATERIAL GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF FINANCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 2013 (Eleventh Edition: 11th September, 2013) Preface to the 11th Edition The Department of Pension and Administrative Reforms had issued instructions in 1978 that each Ministry/Department should prepare an Induction Material setting out the aims and objects of the Department, detailed functions of the various divisions and their inter-relationship which would be useful for the officers of the Ministry/Department particularly the new entrants. In pursuance to this, Department of Economic Affairs has been bringing out ‘Induction Material’ since 1981. The present Edition is Eleventh in the series. 2. Department of Economic Affairs is the nodal agency of the Government of India for formulation of economic policies and programmes. In the present day context of global economic slowdown, the role of the Department of Economic Affairs has assumed a special significance. An attempt has been made to delineate the activities of the Department in a manner that would help the reader accurately appreciate its role. 3. The Induction Material sets out to unfold the working of the Department up to the level of the Primary Functional Units, i.e. Sections. All members of the team should find it useful to identify those concerned with any particular item of work right upto the level of Section Officer. The other Ministries and Departments will also find it useful in identifying the division or the officer to whom the papers are to be addressed. 4. I hope that all users will find this edition of Induction Material a handy and useful guide to the functioning of the Department of Economic Affairs. -

Annual Report 2012-2013

Annual Report 2012-2013 Ministry of External Affairs New Delhi Published by: Policy Planning and Research Division, Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi This Annual Report can also be accessed at website: www.mea.gov.in The front cover depicts South Block, seat of Ministry of External Affairs since 1947. The inside of front cover shows Jawaharlal Nehru Bhawan, Ministry of External Affairs’ new building since June 2011. The inside of back cover shows displays at Jawaharlal Nehru Bhawan Designed and printed by: Graphic Point Pvt. Ltd. 4th Floor, Harwans Bhawan II Nangal Rai, Commercial Complex New Delhi 110 046 Ph. 011-28523517 E-Mail. [email protected] Content Introduction and Synopsis i-xvii 1. India's Neighbours 1 2. South-East Asia and the Pacific 16 3. East Asia 28 4. Eurasia 33 5. The Gulf and West Asia 41 6. Africa 48 7. Europe and European Union 63 8. The Americas 80 9. United Nations and International Organizations 94 10. Disarmament and International Security Affairs 108 11. Multilateral Economic Relations 112 12. South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation 119 13. Development Cooperation 121 14. Investment and Technology Promotion 127 15. Energy Security 128 16. Counter Terrorism and Policy Planning 130 17. Protocol 132 18. Consular, Passport and Visa Services 139 19. Administration and Establishment 146 20. Right to Information and Chief Public Information Office 149 21. e-Governance and Information Technology 150 22. Coordination Division 151 23. External Publicity 152 24. Public Diplomacy 155 25. Foreign Service Institute 159 26. Implementation of Official Language Policy and Propagation of Hindi Abroad 161 27. -

Alphabetical List of Recommendations Received for Padma Awards - 2014

Alphabetical List of recommendations received for Padma Awards - 2014 Sl. No. Name Recommending Authority 1. Shri Manoj Tibrewal Aakash Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal, Minister of Coal, Govt. of India. 2. Dr. (Smt.) Durga Pathak Aarti 1.Dr. Raman Singh, Chief Minister, Govt. of Chhattisgarh. 2.Shri Madhusudan Yadav, MP, Lok Sabha. 3.Shri Motilal Vora, MP, Rajya Sabha. 4.Shri Nand Kumar Saay, MP, Rajya Sabha. 5.Shri Nirmal Kumar Richhariya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh. 6.Shri N.K. Richarya, Chhattisgarh. 3. Dr. Naheed Abidi Dr. Karan Singh, MP, Rajya Sabha & Padma Vibhushan awardee. 4. Dr. Thomas Abraham Shri Inder Singh, Chairman, Global Organization of People Indian Origin, USA. 5. Dr. Yash Pal Abrol Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, Padma Vibhushan awardee. 6. Shri S.K. Acharigi Self 7. Dr. Subrat Kumar Acharya Padma Award Committee. 8. Shri Achintya Kumar Acharya Self 9. Dr. Hariram Acharya Government of Rajasthan. 10. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 11. Shri Somnath Adhikary Self 12. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao Shri Ganta Srinivasa Rao, Minister for Infrastructure & Investments, Ports, Airporst & Natural Gas, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh. 13. Prof. S.H. Advani Dr. S.K. Rana, Consultant Cardiologist & Physician, Kolkata. 14. Shri Vikas Agarwal Self 15. Prof. Amar Agarwal Shri M. Anandan, MP, Lok Sabha. 16. Shri Apoorv Agarwal 1.Shri Praveen Singh Aron, MP, Lok Sabha. 2.Dr. Arun Kumar Saxena, MLA, Uttar Pradesh. 17. Shri Uttam Prakash Agarwal Dr. Deepak K. Tempe, Dean, Maulana Azad Medical College. 18. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 1.Dr. Ashok Kumar Walia, Minister of Health & Family Welfare, Higher Education & TTE, Skill Mission/Labour, Irrigation & Floods Control, Govt. -

Standing Committee on Defence (2009-2010)

4 STANDING COMMITTEE ON DEFENCE (2009-2010) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF DEFENCE [Action Taken by the Government on the Recommendations contained in the Thirty-first Report of the Committee (Fourteenth Lok Sabha) on ‘Stress Management in Armed Forces’] FOURTH REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2010/Phalguna, 1931 (Saka) FOURTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON DEFENCE (2009-2010) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF DEFENCE [Action Taken by the Government on the Recommendations contained in the Thirty-first Report of the Committee (Fourteenth Lok Sabha) on ‘Stress Management in Armed Forces’] Presented to Lok Sabha on 04.03.2010 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 04.03.2010 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2010/Phalguna, 1931 (Saka) C.O.D. No.113 Price: Rs. © 2010 By LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Twelfth Edition) and printed by …………………. (i) CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2009-2010).……………………. (iii) INTRODUCTION.…………………………………………………….… ………. (iv) CHAPTER I Report ……………………………………………….…. 1 CHAPTER II Recommendations/Observations which have been accepted by the Government…….……………….…... 12 CHAPTER III Recommendation/Observations which the Committee do not desire to pursue in view of Government’s replies…………………………………..…..……….….… 27 CHAPTER IV Recommendations/Observations in respect of which replies of Government have not been accepted by the committee………………………..….…………..…… 28 CHAPTER V Recommendations/Observations in respect of which final replies of Government are still awaited. ………… 34 MINUTES OF THE SITTING ………………………………………………… .35 ANNEXURE ………………………………………………………………37 APPENDIX Analysis of Action Taken by the Government on the recommendations contained in the 31st Report of the Standing Committee on Defence (Fourteenth Lok Sabha)………………………………………………….… 43 (ii) COMPOSITION OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON DEFENCE (2009-10) Shri Satpal Maharaj - Chairman MEMBERS LOK SABHA 2.