Reflections of Science and Technology in American Drama from 1913 to 1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

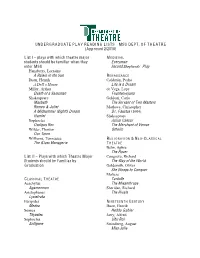

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

O'neill Society News

Boston International Conference June 17-20, 2020 @ Suffolk University Fall 2019 O’Neill Society News The official newsletter of the Eugene O’Neill International Society Contents • EON Society at ALA 2019 .................2 • A Tribute to Kurt Eisen ......................2 • Society Annual Business Mtg .........3 • ALA Conference May 2019 in Boston and 2020 Conference Update....................................................3 • Peter Quinn wins O’Neill Award ....3 • O’Neill Festivals in Danville, CA and New Ross, Ireland ...............................4 • Eisel Reflections on Long Day’s ......5 • Babson Students to Tao House ......5 • Dowling on NPR Radio Show .........5 • Grad Student Paper Competition .5 • New Film on Charles Gilpin ............5 • 2020 Conferences for O’Neillians .6 • Garvey Comes Full Circle .................6 • Photos from Recent Productions of O’Neill plays .........................................7 O’Neill Conferences, Festivals and • Opportunity for ePublishing ..........8 • Review celebrates 5th Decade .......8 Performances Around the Globe The summer and fall were filled with multiple conferences, festivals and regional performances of plays by Eugene O’Neill. The activities took place in the hills of Danville, CA, at Tao House; at the American Literature Association Conference in Boston, MA; in New Ross, Ireland at the Eugene O’Neill Theatre Festival, and many stops in between. We’ll highlight these events in this edition of the newsletter! Word came just as we were going to press that O’Neill Society member, celebrated scholar and poet George Monteiro died suddenly from a heart attack on Tuesday, November 5. His wife Brenda Murphy reported that he had been dealing with debilitating neurological problems for several years, a “Parkinsonism” not unlike Eugene O’Neill’s. -

The Philosophy of Eugene O'neill

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1929 The Philosophy of Eugene O'Neill Judith Reynick Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Reynick, Judith, "The Philosophy of Eugene O'Neill" (1929). Master's Theses. 440. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/440 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1929 Judith Reynick THE FrlILO~OPHY OF EUG~~B O'NEILL JUDITH Ri!."'YN 10K A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements i'or the degree of Master of Arts in Loyola University 1929 Judi th Reyni ck University of Chicago, Ph.B., 1921 • . Teacher of English, Schurz High School. TABLE ·OF GON'r~ . I. INTRODUCTION . 1. ate. temen t of problem 2. Method of dealing with problem·: 3. Brief sketch of au thor GROUPING' Romantic or objective Xaturalistic and autobiographical 3. Symbolic and subjective OONOLUS,IONS IV. LIS T OF PLAYS RE.'V lEi/ED v. BIBLIOGRAPHY F'..;:;",.-o_-----------------:--------, Eugene O'Neill, the American playwrightl That these terms are almost synonymous is the conclusion one is tl forced to, if , to him, a study of contemporary dramatic criticism of the last fourteen years is any criterion. -

Biography of Eugene O'neill

Biography of Eugene O’Neill Trevor M. Wise Eugene Gladstone O’Neill was born on October 16, 1888, at the Barrett hotel in New York city, New York, son of James o’Neill, a well-known matinee idol, and Mary Ellen (Ella) Quinlan. Much of O’Neill’s youth was spent in the wings of the theater as he toured the country with his parents and older brother Jamie, watching his father perform his most famous role—the Count of Monte Cristo. When not touring the country with his family, O’Neill attended Catholic boarding school at St. Aloysius Academy at Mount Saint Vincent in the Bronx borough of New York. he then spent four years at Betts Academy, a non-sectarian prep school in Stamford, Connecticut. O’Neill spent the summers with his family at the Monte Cristo Cottage in New London, Connecticut, the only permanent home O’Neill knew as a child. in 1903, at the age of fifteen, o’Neill became aware of his mother’s morphine addiction and was introduced to alcohol by his brother Jamie, setting him on a path of heavy drinking and alcohol abuse. in the fall of 1906, o’Neill enrolled in princeton University, only to be expelled in the following spring for his poor academic per- formance. in october 1909, o’Neill secretly married Kathleen Jenkins, his first of three wives. Shortly after the wedding, o’Neill set sail for honduras to prospect for gold, but found none. While abroad, O’Neill lived the life of a waterfront derelict, working odd jobs and drinking heavily, until he contracted malaria and was forced to return to the United States. -

ANTA Theater and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission August 6, 1985; Designation List 182 l.P-1309 ANTA THFATER (originally Guild Theater, noN Virginia Theater), 243-259 West 52nd Street, Manhattan. Built 1924-25; architects, Crane & Franzheim. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1024, Lot 7. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the ANTA Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty-three witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The ANTA Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in the 1924-25, the ANTA was constructed for the Theater Guild as a subscription playhouse, named the Guild Theater. The fourrling Guild members, including actors, playwrights, designers, attorneys and bankers, formed the Theater Guild to present high quality plays which they believed would be artistically superior to the current offerings of the commercial Broadway houses. More than just an auditorium, however, the Guild Theater was designed to be a theater resource center, with classrooms, studios, and a library. The theater also included the rrost up-to-date staging technology. -

American Theatre and Drama Eugene O'neill and His Contemporaries

Theatre 365-1: American Theatre and Drama Eugene O’Neill and His Contemporaries Monday/Wednesday 9:30-10:50am, Parkes Hall 215 Instructor: Shannon K. Fitzsimons ([email protected]) Office Hours: By appointment Course Description This course will examine American drama and theatre history from 1915 to 1945 through the stylistically diverse career of Eugene O'Neill, the only American dramatist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Special emphasis will be placed on O'Neill's early career with the Provincetown Players, the expressionistic experiments of the 1920s, social dramas of the Depression years, and finally, the realist family dramas of the 1940s. Playwrights (besides O'Neill) to be studied include Susan Glaspell, Elmer Rice, Sophie Treadwell, Gertrude Stein, Marc Blitzstein, Clifford Odets, Tennessee Williams, and Arthur Miller. Assignments Discussion Questions Beginning with class on Wednesday, January 4, and continuing through class on Wednesday, February 29, students are required to post TWO discussion questions on the assigned reading(s) for each class on Blackboard. Discussion questions are due by 8 am on the day of class. Students are expected to post discussion questions for 15 of the 17 discussion days; in other words, you may opt to not write questions for two classes of your choice. The discussion questions for each class are worth 1% of your final grade, for a total of 15%. They will be marked on a complete/incomplete basis, with complete questions receiving an A and incomplete questions receiving a zero. Contextual Presentation and Summary/Bibliography Each student will be responsible for presenting one ten-minute in-class presentation on a topic related to the course material; topics for each class meeting are listed on the weekly schedule below and a sign-up sheet for these presentations will be circulated on the first day of class. -

CONTRIBUTION TOWARDS AMERICAN PLAYS by CLIFFORD ODETS and OTHER PLAYWRIGHTS DURING 1930S

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347-4564; ISSN (E): 2321-8878 Vol. 6, Issue 4, Apr 2018, 51-56 © Impact Journals CONTRIBUTION TOWARDS AMERICAN PLAYS BY CLIFFORD ODETS AND OTHER PLAYWRIGHTS DURING 1930s G. Visalam Head, Department of English, Sri Muthukumaran Arts and Science College, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Received: 31 Mar 2018 Accepted: 04 Apr 2018 Published: 07 Apr 2018 ABSTRACT American Plays had a tremendous response during 1930s and several genre of plays were staged at all corners of America and the Americans were fond of enacting and viewing the plays. The genre of plays will vary based on the American people mindset and the political situations. Several playwrights followed Hollywood techniques for writing their scripts. The role of playwright was found to be more vital than the role of an actor or the Director or the Production Company. The contribution of the playwrights during 1930s was considered to be a trend setting period in changing the roles of a writer from technician to becoming an artist. KEYWORDS : Playwright, Writer, Script, Actor, Play, Drama, Theatre INTRODUCTION During the 1930s, the playwrights followed Hollywood’s technique for paying writers for their scripts. Theatres such as Group Theatre and the Theatre Guild supported this idea to consider writers as autonomous artists whose function was very important than any other member of the company. The scripts were sold on the basis of their value, but they were written without the specific actor, particular director or any theatres in mind. Thus the Star System of Pre-World War came to an end, by giving importance to the playwright. -

The Glass Menagerie by TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Directed by JOSEPH HAJ PLAY GUIDE Inside

Wurtele Thrust Stage / Sept 14 – Oct 27, 2019 The Glass Menagerie by TENNESSEE WILLIAMS directed by JOSEPH HAJ PLAY GUIDE Inside THE PLAY Synopsis, Setting and Characters • 4 Responses to The Glass Menagerie • 5 THE PLAYWRIGHT About Tennessee Williams • 8 Tom Is Tom • 11 In Williams’ Own Words • 13 Responses to Williams • 15 CULTURAL CONTEXT St. Louis, Missouri • 18 "The Play Is Memory" • 21 People, Places and Things in the Play • 23 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION For Further Reading and Understanding • 26 Guthrie Theater Play Guide Copyright 2019 DRAMATURG Carla Steen GRAPHIC DESIGNER Akemi Graves CONTRIBUTOR Carla Steen EDITOR Johanna Buch Guthrie Theater, 818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415 All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000 teachers and individual personal use, no part of this Play Guide may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.44.STAGE (toll-free) or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, artistic director writing from the publishers. Some materials published herein are written especially for our Guide. Others are reprinted by permission of their publishers. The Guthrie Theater receives support from the National The Guthrie creates transformative theater experiences that ignite the imagination, Endowment for the Arts. This activity is made possible in part by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation stir the heart, open the mind and build community through the illumination of our by the Minnesota State Legislature. The Minnesota State Arts common humanity. -

Scenes from Opera and Musical Theatre

LEON WILSON CLARK OPERA SERIES SHEPHERD SCHOOL OPERA presents an evening of SCENES FROM OPERA AND MUSICAL THEATRE Debra Dickinson, stage director Thomas Jaber, musical director and pianist January 30 and 31, February 1 and 2, 1998 7:30 p.m. Wortham Opera Theatre RICE UNNERSITY PROGRAM DER FREISCHOTZ Music by Carl Maria von Weber; libretto by Johann Friedrich Act II, scene 1: Schelm, halt' fest// Kommt ein schlanker Bursch gegangen. Agatha: Leslie Heal Annie: Laura D 'Angelo CANDIDE Music by Leonard Bernstein; lyrics by John Latouche, Dorothy Parker, Stephen Sondheim, Richard Wilbur OHappyWe Candide: Matthew Pittman Cunegonde: Sibel Demirmen \. THE THREEPENNY OPERA Music by Kurt Weill; lyrics by Bertolt Brecht The Jealousy Duet Lucy Brown: Aidan Soder Polly Peachum: Kristina Driskill MacHeath: Adam Feriend DON GIOVANNI Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart; libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte Act I, scene 3: Laci darem la mano/Ah! fuggi ii traditor! Don Giovanni: Christopher Holloway Zerlina: Elizabeth Holloway Donna Elvira: Michelle Herbert STREET SCENE Music by Kurt Weill; lyrics by Elmer Rice Act/I Duet Rose: Adrienne Starr Sam: Matthew Pittman MY FAIR LADY Music by Frederick Loewe; lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner On the Street Where You Live/Show Me Freddy Eynsford Hill: David Ray Eliza Doolittle: Dawn Bennett LA BOHEME Music by Giacomo Puccini; libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica Act/II Mimi: Kristin Nelson Marcello: Matthew George Rodolfo: Creighton Rumph Musetta: Adrienne Starr Directed by Elizabeth Holloway INTERMISSION LE NOZZE DI FIGARO -

Drake Plays 1927-2021.Xls

Drake Plays 1927-2021.xls TITLE OF PLAY 1927-8 Dulcy SEASON You and I Tragedy of Nan Twelfth Night 1928-9 The Patsy SEASON The Passing of the Third Floor Back The Circle A Midsummer Night's Dream 1929-30 The Swan SEASON John Ferguson Tartuffe Emperor Jones 1930-1 He Who Gets Slapped SEASON Miss Lulu Bett The Magistrate Hedda Gabler 1931-2 The Royal Family SEASON Children of the Moon Berkeley Square Antigone 1932-3 The Perfect Alibi SEASON Death Takes a Holiday No More Frontier Arms and the Man Twelfth Night Dulcy 1933-4 Our Children SEASON The Bohemian Girl The Black Flamingo The Importance of Being Earnest Much Ado About Nothing The Three Cornered Moon 1934-5 You Never Can Tell SEASON The Patriarch Another Language The Criminal Code 1935-6 The Tavern SEASON Cradle Song Journey's End Good Hope Elizabeth the Queen 1936-7 Squaring the Circle SEASON The Joyous Season Drake Plays 1927-2021.xls Moor Born Noah Richard of Bordeaux 1937-8 Dracula SEASON Winterset Daugthers of Atreus Ladies of the Jury As You Like It 1938-9 The Bishop Misbehaves SEASON Enter Madame Spring Dance Mrs. Moonlight Caponsacchi 1939-40 Laburnam Grove SEASON The Ghost of Yankee Doodle Wuthering Heights Shadow and Substance Saint Joan 1940-1 The Return of the Vagabond SEASON Pride and Prejudice Wingless Victory Brief Music A Winter's Tale Alison's House 1941-2 Petrified Forest SEASON Journey to Jerusalem Stage Door My Heart's in the Highlands Thunder Rock 1942-3 The Eve of St. -

The Work of the Little Theatres

TABLE OF CONTENTS PART THREE PAGE Dramatic Contests.144 I. Play Tournaments.144 1. Little Theatre Groups .... 149 Conditions Eavoring the Rise of Tournaments.150 How Expenses Are Met . -153 Qualifications of Competing Groups 156 Arranging the Tournament Pro¬ gram 157 Setting the Tournament Stage 160 Persons Who J udge . 163 Methods of Judging . 164 The Prizes . 167 Social Features . 170 2. College Dramatic Societies 172 3. High School Clubs and Classes 174 Florida University Extension Con¬ tests .... 175 Southern College, Lakeland, Florida 178 Northeast Missouri State Teachers College.179 New York University . .179 Williams School, Ithaca, New York 179 University of North Dakota . .180 Pawtucket High School . .180 4. Miscellaneous Non-Dramatic Asso¬ ciations .181 New York Community Dramatics Contests.181 New Jersey Federation of Women’s Clubs.185 Dramatic Work Suitable for Chil¬ dren .187 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE II. Play-Writing Contests . 188 1. Little Theatre Groups . 189 2. Universities and Colleges . I9I 3. Miscellaneous Groups . • 194 PART FOUR Selected Bibliography for Amateur Workers IN THE Drama.196 General.196 Production.197 Stagecraft: Settings, Lighting, and so forth . 199 Costuming.201 Make-up.203 Acting.204 Playwriting.205 Puppetry and Pantomime.205 School Dramatics. 207 Religious Dramatics.208 Addresses OF Publishers.210 Index OF Authors.214 5 LIST OF TABLES PAGE 1. Distribution of 789 Little Theatre Groups Listed in the Billboard of the Drama Magazine from October, 1925 through May, 1929, by Type of Organization . 22 2. Distribution by States of 1,000 Little Theatre Groups Listed in the Billboard from October, 1925 through June, 1931.25 3.