Podcast, Brought to You by the Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organizing Screens with Mission Control | 61

Organizing Screens with 7 Mission Control If you’re like a lot of Mac users, you like to do a lot of things at once. No matter how big your screen may be, it can still feel crowded as you open and arrange multiple windows on the desktop. The solution to the problem? Mission Control. The idea behind Mission Control is to show what you’re running all at once. It allows you to quickly swap programs. In addition, Mission Control lets you create multiple virtual desktops (called Spaces) that you can display one at a time. By storing one or more program windows in a single space, you can keep open windows organized without cluttering up a single screen. When you want to view another window, just switch to a different virtual desktop. Project goal: Learn to use Mission Control to create and manage virtual desktops (Spaces). My New Mac, Lion Edition © 2011 by Wallace Wang lion_book-4c.indb 59 9/9/2011 12:04:57 PM What You’ll Be Using To learn how to switch through multiple virtual desktops (Spaces) on your Macintosh using Mission Control, you’ll use the following: > Mission Control > The Safari web browser > The Finder program Starting Mission Control Initially, your Macintosh displays a single desktop, which is what you see when you start up your Macintosh. When you want to create additional virtual desktops, or Spaces, you’ll need to start Mission Control. There are three ways to start Mission Control: > Start Mission Control from the Applications folder or Dock. > Press F9. -

Mac Keyboard Shortcuts Cut, Copy, Paste, and Other Common Shortcuts

Mac keyboard shortcuts By pressing a combination of keys, you can do things that normally need a mouse, trackpad, or other input device. To use a keyboard shortcut, hold down one or more modifier keys while pressing the last key of the shortcut. For example, to use the shortcut Command-C (copy), hold down Command, press C, then release both keys. Mac menus and keyboards often use symbols for certain keys, including the modifier keys: Command ⌘ Option ⌥ Caps Lock ⇪ Shift ⇧ Control ⌃ Fn If you're using a keyboard made for Windows PCs, use the Alt key instead of Option, and the Windows logo key instead of Command. Some Mac keyboards and shortcuts use special keys in the top row, which include icons for volume, display brightness, and other functions. Press the icon key to perform that function, or combine it with the Fn key to use it as an F1, F2, F3, or other standard function key. To learn more shortcuts, check the menus of the app you're using. Every app can have its own shortcuts, and shortcuts that work in one app may not work in another. Cut, copy, paste, and other common shortcuts Shortcut Description Command-X Cut: Remove the selected item and copy it to the Clipboard. Command-C Copy the selected item to the Clipboard. This also works for files in the Finder. Command-V Paste the contents of the Clipboard into the current document or app. This also works for files in the Finder. Command-Z Undo the previous command. You can then press Command-Shift-Z to Redo, reversing the undo command. -

OS X Mountain Lion Includes Ebook & Learn Os X Mountain Lion— Video Access the Quick and Easy Way!

Final spine = 1.2656” VISUAL QUICKSTA RT GUIDEIn full color VISUAL QUICKSTART GUIDE VISUAL QUICKSTART GUIDE OS X Mountain Lion X Mountain OS INCLUDES eBOOK & Learn OS X Mountain Lion— VIDEO ACCESS the quick and easy way! • Three ways to learn! Now you can curl up with the book, learn on the mobile device of your choice, or watch an expert guide you through the core features of Mountain Lion. This book includes an eBook version and the OS X Mountain Lion: Video QuickStart for the same price! OS X Mountain Lion • Concise steps and explanations let you get up and running in no time. • Essential reference guide keeps you coming back again and again. • Whether you’re new to OS X or you’ve been using it for years, this book has something for you—from Mountain Lion’s great new productivity tools such as Reminders and Notes and Notification Center to full iCloud integration—and much, much more! VISUAL • Visit the companion website at www.mariasguides.com for additional resources. QUICK Maria Langer is a freelance writer who has been writing about Mac OS since 1990. She is the author of more than 75 books and hundreds of articles about using computers. When Maria is not writing, she’s offering S T tours, day trips, and multiday excursions by helicopter for Flying M Air, A LLC. Her blog, An Eclectic Mind, can be found at www.marialanger.com. RT GUIDE Peachpit Press COVERS: OS X 10.8 US $29.99 CAN $30.99 UK £21.99 www.peachpit.com CATEGORY: Operating Systems / OS X ISBN-13: 978-0-321-85788-0 ISBN-10: 0-321-85788-7 BOOK LEVEL: Beginning / Intermediate LAN MARIA LANGER 52999 AUTHOR PHOTO: Jeff Kida G COVER IMAGE: © Geoffrey Kuchera / shutterstock.com ER 9 780321 857880 THREE WAYS To learn—prINT, eBOOK & VIDEO! VISUAL QUICKSTART GUIDE OS X Mountain Lion MARIA LANGER Peachpit Press Visual QuickStart Guide OS X Mountain Lion Maria Langer Peachpit Press www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected]. -

Apple for Newbies

Apple for Newbies While Macs are technically personal computers (PCs), the term PC is often used to describe computers that run Windows or Linux. Therefore, Macs are often referred to as personal computers, but not PCs. Unlike PCs, which are manufactured by several different companies, Apple designs and manufactures all Macintosh computers. Dock Select an item in the Dock: click its icon. When an application is running, the Dock displays an illuminated dash beneath the application's icon. To make any currently running application the active one, click its icon in the Dock to switch to it (the active application's name appears in the menu bar to the right of the Apple logo). As you open applications, their respective icons appear in the Dock, even if they weren't there originally. That means if you've got a lot of applications open, your Dock will grow substantially. If you minimize a window, the window gets pulled down into the Dock and waits until you click this icon to bring up the window again. The Dock keeps applications on its left side, while Stacks and minimized windows are kept on its right. If you look closely, you'll see a vertical separator line that separates them. If you want to rearrange where the icons appear within their line limits, just drag a docked icon to another location on the Dock and drop it. Tip: Control-click or right-click a Dock item to see a contextual menu of additional choices. Adding and removing Dock items 1. Add an item to the Dock: Click the Launchpad icon in the Dock and drag the application icon to the Dock; the icons in the Dock will move aside to make room for the new one. -

Pro Tools 2020.9 Read Me (Macos)

Read Me Pro Tools and Pro Tools | Ultimate Software 2020.9 on macOS 10.13.6, 10.14.6, and 10.15.6 This Read Me documents important compatibility information and known issues for Pro Tools® and Pro Tools | Utimate Software 2020.9 on macOS 10.13.6 (“High Sierra”), 10.14.6 (“Mojave”), and 10.15.6 (“Catalina”). For detailed compatibility information, including supported operating systems, visit the Pro Tools compatibility pages online. Compatibility Avid can only assure compatibility and provide support for qualified hardware and software configurations. For the latest compatibility information—including qualified computers, operating systems, and third-party products—visit the Avid website (www.avid.com/compatibility). General Compatibility Pro Tools would like to access files on a removable volume. (PT-256794) macOS 10.15 (“Catalina”) introduces a new dialog that controls application access to external volumes. You may encounter this dialog when launching Pro Tools or when mounting a new volume with Pro Tools open. Clicking OK lets Pro Tools see the media on this vol- ume for use with sessions, as well as an available volume in the Workspace. It is recommended that you click OK, but even if you click Don't Allow instead you can still allow this later in the macOS System Preferences > Security & Privacy settings. Pro Tools legacy key commands in the Import Audio dialog conflict with Finder commands in Catalina (PT-257178) The legacy keyboard shortcuts in the Import Audio dialog no longer function as expected on macOS Catalina. The legacy shortcuts continue to work on macOS Mohave and earlier. -

Successful Application of New Technologies to the Rosetta and Mars Express Simulators

white paper Successful Application of New Technologies to the Rosetta and Mars Express Simulators J. Martin, J. Ochs 1 VEGA GmbH, Hilperstrasse 20A, D-64295, Darmstadt, Germany Abstract VEGA is currently in the final stages of implementing the Rosetta and Mars Express simulators for the European Space Operation Centre (ESOC). Both simulators are high fidelity, entirely software-based tools principally used for training the operations team. This paper describes aspects of the development of the simulator, in particular focussing upon the application of new technologies, the re-use of previously developed models and infrastructures, and the potential re-use of the new technologies in future simulators. Introduction VEGA won the contract to supply both the Rosetta and Mars Express simulators to ESOC. The two simulators were to be developed concurrently and with a fixed schedule. Due to hardware re-use on the spacecraft, VEGA was able to establish a common code-base for the two simulators, which has simplified the overall development. Each simulator contains a high fidelity model of the spacecraft platform. In comparison, the scientific payload instruments have been modelled in a generic, lower fidelity manner, but incorporate a higher degree of user configurability. Such an approach allows the payload models to be readily updated should the need arise. In response to customer requirements, and as a result of simulator design, it was found necessary to utilize a host of new technologies, not least the infrastructure within which the simulators run. However, all parts of the simulators are not new. In fact, the design also incorporates models and infrastructures re-used from other VEGA and ESA projects. -

Configurations, Troubleshooting, and Advanced Secure Browser Installation Guide for OS X/Macos and Ios/Ipados

Configurations, Troubleshooting, and Advanced Secure Browser Installation Guide for OS X/macOS and iOS/iPadOS 2020–2021 Updated 4/20/2021 1 Table of Contents Configurations, Troubleshooting, and Secure Browser Installation for OS X/macOS and iOS/iPadOS .............................................................................................................................................3 How to Configure OS X/macOS Workstations for Online Testing .............................................................. 3 Installing the Secure Profile for OS X/macOS ...........................................................................................4 Installing Secure Browser for OS X/macOS ..............................................................................................5 Installing the SecureTestBrowser App for iOS/iPadOS ............................................................................. 5 Additional Instructions for Installing the Secure Browser for OS X/macOS ................................................ 6 Cloning the Secure Browser Installation to Other OS X/macOS Machines ........................................ 6 Uninstalling the Secure Browser on OS X/macOS ............................................................................ 7 Additional Configurations for OS X/macOS ...............................................................................................7 Disabling Updates to Third-Party Apps .............................................................................................7 -

GAO-19-136, DOD SPACE ACQUISITIONS: Including Users

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees March 2019 DOD SPACE ACQUISITIONS Including Users Early and Often in Software Development Could Benefit Programs GAO-19-136 March 2019 DOD SPACE ACQUISITIONS Including Users Early and Often in Software Development Could Benefit Programs Highlights of GAO-19-136, a report to congressional committees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Over the next 5 years, DOD plans to The four major Department of Defense (DOD) software-intensive space spend over $65 billion on its space programs that GAO reviewed struggled to effectively engage system users. system acquisitions portfolio, including These programs are the Air Force’s Joint Space Operations Center Mission many systems that rely on software for System Increment 2 (JMS), Next Generation Operational Control System (OCX), key capabilities. However, software- Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS); and the Navy’s Mobile User Objective intensive space systems have had a System (MUOS). These ongoing programs are estimated to cost billions of history of significant schedule delays dollars, have experienced overruns of up to three times originally estimated cost, and billions of dollars in cost growth. and have been in development for periods ranging from 5 to over 20 years. Senate and House reports Previous GAO reports, as well as DOD and industry studies, have found that accompanying the National Defense user involvement is critical to the success of any software development effort. Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017 For example, GAO previously reported that obtaining frequent feedback is linked contained provisions for GAO to review to reducing risk, improving customer commitment, and improving technical staff challenges in software-intensive DOD motivation. -

Apple and Student Assessment 2020

Apple and Student Assessment iPad and Mac are powerful learning devices that you can use for all forms of assessment, including secure exams that can be automatically configured using assessment mode. Approved for standardized assessments in all states, iPad and Mac offer an array of formative learning apps for evaluating students’ progress long-term as they prepare for statewide testing. iPad for state testing As iPad transforms the classroom and expands the possibilities for teaching and learning, educators have also come to rely on iPad for daily learning and student assessment. Schools can disable certain hardware and software features during online assessments to meet test security requirements and prevent test takers from circumventing the assessment and invalidating test results. Assessment mode on iPad Set up iPad for state testing Setup and management for testing on iPad is streamlined and With assessment mode, you can set up iPad for testing in just one simple. Here are just a few of the benefits of assessment on iPad: step: installing your state testing app on iPad. No further setup or management is required. Your state testing app will automatically lock • Compliant. All state summative and interim assessments support and configure iPad for testing each time the app is launched. After a iPad, including Cambium (SBAC) and ACT Aspire. iPad meets student completes the test and signs out from the testing app, iPad hardware and comparability standards and can be configured to automatically returns to general use settings. provide a secure test environment. Check with your state testing agency for their guidelines. Check with your testing provider to confirm assessment mode support. -

Macbook Tips & Tricks

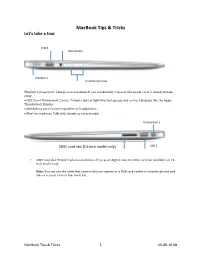

MacBook Tips & Tricks Let’s take a tour USB 3 Headphones MegSafe 2 Dual Microphones MagSafe 2 power port: Charge your notebook. If you accidentally trip over the power cord, it cleanly breaks away. ••USB 3 and Thunderbolt 2 ports: Transfer data at lightning-fast speeds and connect displays like the Apple Thunderbolt Display. ••Headphone port: Connect speakers or headphones. ••Dual microphones: Talk with friends or record audio ThunderBolt 2 USB 3 SDXC card slot (13-inch model only) • SDXC card slot: Transfer photos and videos from your digital camera. SDXC card slot available on 13- inch model only. Note: You can use the cable that came with your camera or a USB card reader to transfer photos and videos to your 11-inch MacBook Air. MacBook Tips & Tricks 1 03-08-16 KB Desktop The desktop is the first thing you see when you turn on your laptop. It has the Apple menu at the top and the Dock at the bottom. Dock MacBook Tips & Tricks 2 03-08-16 KB Launchpad Launchpad makes your desktop look and act like an iPad. All your apps will be available from here. Finder Finder is your file management system. Use it to organize your files or access network drives like your H: drive. System Preferences Two places where you can access system preferences MacBook Tips & Tricks 3 03-08-16 KB Trackpad and Gestures The trackpad replaces the external mouse and utilizes gestures to perform actions on the computer. You can make customize to your style. Keyboard Shortcut link https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT201236 Keyboard shortcuts o Shift + Control + Power -

Intermediate Apple Resources Check out Us

Intermediate Apple Resources 13 April 2018, 7:00pm Common and Useful Keyboard Shortcuts Shortcut Description Command + C Copy selected text, item, or file Command + X Cut selected text or item Command + V Paste copied or cut items or text Command + A Select all text or items. Command + S Save the current file or document Command + P Print the current document or window Open a selected item or the dialog box to select Command + O a file Command + F Find items in a file or document Command + Q Quit the current app Option + Command + Esc Open the Force Quit menu Command + Space Open the Spotlight search field Command + Shift + 3 Take a Screenshot of the entire screen Command + Shift + 4 Select an area of the screen for a Screenshot Command + Tab Switch to the last used app Control + Up arrow/Down arrow Open/close Mission Control Control + Left/Right arrow Switch between Spaces Check out https://support.apple.com/en- us/HT201236 to learn more about keyboard shortcuts. 5215 Oakton Street / Skokie, IL 60077 / 847-673-7774 / www.skokielibrary.info Intermediate Apple Resources 13 April 2018, 7:00pm Web Resources Lifewire Mac How-Tos—https://www.lifewire.com/learn-how-macs-4102760 • Learn about iTunes and the Itunes Store in this comprehensive series of articles— https://www.lifewire.com/itunes-itunes-store-guide-1999711 iMore Apple How-Tos—https://www.imore.com/how-to • Try this comprehensive tutorial on working with windows in mac OS— https://www.imore.com/manage-your-windows-pro-macos Apple Support for Mac—https://support.apple.com/mac • Check out Apple Support’s article about the Photos app— https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT206186 • Or the article about setting up custom keyboard shortcuts— https://support.apple.com/kb/PH25377?locale=en_US Lynda.com Video Tutorials macOS High Sierra Essential Training with Nick Brazzi Access this tutorial by Lynda.com with your Skokie Public Library card. -

Mac Mini Quick Start Guide

Welcome to your new Mac mini. We’d like to show you around. Let’s get started Let’s get moving Get to know your desktop iCloud Launchpad Mission Control HDMI to DVI AC power When you start your Mac mini for the first time, Setup Assistant helps you It’s easy to move files like documents, email, photos, music, and movies The desktop is where you can find everything and do anything on your Mac. iCloud stores your music, photos, documents, calendars, and more. And adapter cord get going. Just follow a few simple steps to quickly connect to your Wi-Fi to your new Mac from another Mac or a PC. The first time you start your The Dock at the bottom is a handy place to keep the apps you use most. It’s it wirelessly pushes them to your Mac, iPhone, iPad, iPod touch, and even Launchpad is the home for all the group them together in folders, Mission Control gives you a screen apps, and Dashboard, the network, transfer your stuff from another Mac or a PC, and create a user new Mac, it walks you through the process step by step. All you have to also where you can open System Preferences, which lets you customize your your PC. All without docking or syncing. So when you buy a song on one apps on your Mac. Just click the or delete them from your Mac. bird’s-eye view of everything home of mini-apps called widgets. account for your Mac. do is follow the onscreen instructions.