Out of the Dark: Short Fiction - Works in Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

The Devotion Booklet for Children!

Live with Flair Summer Devotions 2012 © Heather Holleman, [email protected] 30 Things You Need to Know I invited Jesus to come into my heart when I was twelve years old. Why did I do this? Well, I wanted to be good, but deep within my heart, I knew how even in all my efforts to be a good little girl, I could not ever be perfect. I also knew that something was wrong with me (and with the whole world for that matter). I learned that this wrongness is what the Bible calls “sin.” Sin separated me from the Loving God I wanted to know. Sin made the world an often sad and lonely place. When I heard that God came to earth to remove the sin that separated me from God, I wanted to hear more. I wanted to know this God who could solve the problem of sin. I learned that Jesus Christ removed sin by His death on the cross, but I had to receive His offer to forgive me of my sin. I had to personally invite Jesus to come into my life, wipe away my sin, and bring me into a relationship with that Loving God I longed to know. Inviting Jesus into my heart was the best decision I ever made. Over the next 25 years, I learned so many secrets from God about how to live my life. Now that I am a mother, I wanted to teach you—and other children (and their moms!)—all the things you need to know in order to grow into the young ladies God wants you to become. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

WDAM Radio's History of Elvis Presley

Listeners Guide To WDAM Radio’s History of Elvis Presley This is the most comprehensive collection ever assembled of Elvis Presley’s “charted” hit singles, including the original versions of songs he covered, as well as other artists’ hit covers of songs first recorded by Elvis plus songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis! More than a decade in the making and an ongoing work-in-progress for the coming decades, this collection includes many WDAM Radio exclusives – songs you likely will not find anywhere else on this planet. Some of these, such as the original version of Muss I Denn (later recorded by Elvis as Wooden Heart) and Liebestraum No. 3 later recorded by Elvis as Today, Tomorrow And Forever) were provided by academicians, scholars, and collectors from cylinders or 78s known to be the only copies in the world. Once they heard about this WDAM Radio project, they graciously donated dubs for this archive – with the caveat that they would never be duplicated for commercial use and restricted only to musicologists and scholarly purposes. This collection is divided into four parts: (1) All of Elvis Presley’s charted U S singles hits in chronological order – (2) All of Elvis Presley’s charted U S and U K singles, the original versions of these songs by other artists, and hit versions by other artists of songs that Elvis Presley recorded first or had a cover hit – in chronological order, along with relevant parody/answer tunes – (3) Songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis Presley – mostly, but not all in chronological order – and (4) X-rated or “adult-themed” songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis Presley. -

Augsome Karaoke Song List Page 1

AUGSome Karaoke Song List 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 112 - Come See Me 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only You 112 - Peaches And Cream 112 - U Already Know 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Amber 311 - Beyond The Gray Sky 311 - Creatures (For A While) 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - Down 311 - First Straw 311 - Hey You 311 - I'll Be Here Awhile 311 - Love Song 311 - You Wouldn't Believe 411 - Dumb 411 - On My Knees 411 - Teardrops 702 - Get It Together 702 - I Still Love You 702 - Steelo 702 - Where My Girls At 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More, A 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 1927 - That's When I Think Of You 1975 - Chocolate 1975 - City 1975 - Love Me 1975 - Robbers 1975 - Sex 1975 - Sound 1975 - Ugh 1 Giant Leap And Jazz Maxi - My Culture 10 Years - Beautiful 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs - Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping Page 1 AUGSome Karaoke Song List 101 Dalmations - Cruella de Vil 10Cc - Donna 10Cc - Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc - I'm Mandy 10Cc - I'm Not In Love 10Cc - Rubber Bullets 10Cc - Things We Do For Love, The 10Cc - Wall Street Shuffle 112 And Ludacris - Hot And Wet 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 12 Stones - Crash 12 Stones - We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3700-3999

RCA Discography Part 12 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3700-3999 LPM/LSP 3700 – Norma Jean Sings Porter Wagoner – Norma Jean [1967] Dooley/Eat, Drink And Be Merry/Country Music Has Gone To Town/Misery Loves Company/Company's Comin'/I've Enjoyed As Much Of This As I Can Stand/Howdy Neighbor, Howdy/I Just Came To Smell The Flowers/A Satisfied Mind/If Jesus Came To Your House/Your Old Love Letters/I Thought I Heard You Calling My Name LPM/LSP 3701 – It Ain’t necessarily Square – Homer and Jethro [1967] Call Me/Lil' Darlin'/Broadway/More/Cute/Liza/The Shadow Of Your Smile/The Sweetest Sounds/Shiny Stockings/Satin Doll/Take The "A" Train LPM/LSP 3702 – Spinout (Soundtrack) – Elvis Presley [1966] Stop, Look And Listen/Adam And Evil/All That I Am/Never Say Yes/Am I Ready/Beach Shack/Spinout/Smorgasbord/I'll Be Back/Tomorrow Is A Long Time/Down In The Alley/I'll Remember You LPM/LSP 3703 – In Gospel Country – Statesmen Quartet [1967] Brighten The Corner Where You Are/Give Me Light/When You've Really Met The Lord/Just Over In The Glory-Land/Grace For Every Need/That Silver-Haired Daddy Of Mine/Where The Milk And Honey Flow/In Jesus' Name, I Will/Watching You/No More/Heaven Is Where You Belong/I Told My Lord LPM/LSP 3704 – Woman, Let Me Sing You a Song – Vernon Oxford [1967] Watermelon Time In Georgia/Woman, Let Me Sing You A Song/Field Of Flowers/Stone By Stone/Let's Take A Cold Shower/Hide/Baby Sister/Goin' Home/Behind Every Good Man There's A Woman/Roll -

Complete Song List

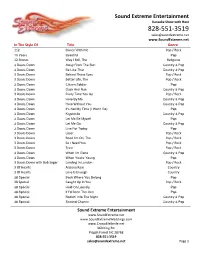

Sound Extreme Entertainment Karaoke Show with Host 828-551-3519 [email protected] www.SoundExtreme.net In The Style Of Title Genre 112 Dance With Me Pop / Rock 10 Years Beautiful Pop 12 Stones Way I Fell, The Religious 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Be Like That Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down Better Life, The Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier Pop 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Every Time You Go Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down Here By Me Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Here Without You Country & Pop 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Pop 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself Pop 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Live For Today Pop 3 Doors Down Loser Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down So I Need You Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down Train Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Country & Pop 3 Doors Down When You're Young Pop 3 Doors Down with Bob Seger Landing In London Pop / Rock 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain Country 3 Of Hearts Love Is Enough Country 38 Special Back Where You Belong Pop 38 Special Caught Up In You Pop / Rock 38 Special Hold On Loosely Pop 38 Special If I'd Been The One Pop 38 Special Rockin' Into The Night Country & Pop 38 Special Second Chance Country & Pop Sound Extreme Entertainment www.SoundExtreme.net www.SoundExtremeWeddings.com www.CrocodileSmile.net 360 King Rd. -

Curb Label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Curb Label Discography

Curb Label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Curb Label Discography Curb Label Distributed by RCA RCA/Curb AHL/PCD 1 5319 — Why Not Me — The Judds [1984] Why Not Me/Mr. Pain/Drops Of Water/Sleeping Heart/My Baby's Gone/Bye Bye Baby Blues/Girls Night Out/Love Is Alive/Endless Sleep/Mama He's Crazy *AHL1-7042 — Rockin’ With The Rhythm — The Judds [1985] Cry Myself To Sleep/Dream Chaser/Grandpa (Tell Me ‘Bout The Good Old Days)/Have Mercy/I Wish She Wouldn’t Treat You That Way/If I Were You/River Roll On/Rockin’ With The Rhythm Of The Rain/Tears For You/Working In The Coal Mine *MHL 1-8515 — The Judds — The Judds [1984] Blue Nun Cafe/Change Of Heart/Had A Dream (For The Heart)/Isn’t He A Strange One/John Deere Tractor/Mama He’s Crazy 2070-1 R — Love Can Build A Bridge — The Judds [1990] Are The Roses Not Blooming/Born To Be Blue/Calling In The Wind/In My Dreams/John Deere Tractor/Love Can Build A Bridge/One Hundred And Two/Rompin’ Stompin’ Blues/Talk About Love • This Country’s Rockin’ RCA/Curb Victor 5916 1R — Heartland — The Judds [1987] Don’t Be Cruel/I’m Falling In Love Tonight/Turn It Loose/Old Pictures/Cow Cow Boogie/Maybe Your Baby’s Got The Blues/I Know Where I’m Going/Why Don’t You Believe Me/The Sweetest Gift *6422-1 R — Christmas Time With The Judds — The Judds [1987] Away In A Manger/Beautiful Star Of Bethlehem/Oh Holy Night/Santa Claus Is Comin’ To Town/Silent Night/Silver Bells/What Child Is This/Who Is This Babe/Winter Wonderland *8318-1 R — Greatest Hits — The Judds [1988] Change Of Heart/Cry Myself To Sleep/Girls Night Out/Give A Little Love/Grandpa (Tell Me ‘Bout The Good Old Days)/Have Mercy/Love Is Alive/Rockin’ With The Rhythm Of The Rain/Why Not Me 9595-1 R — River Of Time — The Judds [1989] Cadillac Red/Guardian Angel/Let Me Tell You About Love/Not My Baby/One Man Woman/River Of Time/Sleepless Nights/Water Of Love/Young Love Curb Label Distributed by Elektra Elektra E 100 Series *Elektra-Curb 6E 194 - Family Tradition - Hank Williams Jr. -

4-7-20 Auction Ad with Pix (All 78'S)

John Tefteller’s World’s Rarest Records Address: P. O. Box 1727, Grants Pass, OR 97528-0200 USA Phone: (541) 476–1326 or (800) 955–1326 • FAX: (541) 476–3523 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.tefteller.com Auction closes Tuesday, April 7, 2020 at 7:00 p.m. PT See #26 See #56 All Original 78 rpm Auction R & B Vocal Groups / Gospel Groups / Blues / Rock & Roll / Rockabilly / Country Here we go again with another all 78’s auction from my vaults! Bargains await for those of you that bid on a wide variety. Many of these records are unplayed Old Store Stock! Grading is very strict and any record graded VG+ or better should play Mint. Enjoy the auction! Some very rare items are mixed in with all-time classics and Good luck to all! obscurities. They all have very reasonable starting bids. 31. Billy Ward And His Dominoes — “No Room/ 58. The Flamingos — “When/That’s My Baby” 85. The Marigolds — “Rollin’ Stone/Why Don’t I’d Be Satisfied” FEDERAL 12105 M- CHECKER 815 M- MB $20 You” EXCELLO 2057 MINT OLD STORE R &B Vocal Groups / MB $20 59. The Flamingos — “A Kiss From Your Lips/Get STOCK, CLASSIC MB $25 32. Billy Ward And His Dominoes — “These With It” CHECKER 837 MINT OLD STORE 86. Arthur Lee Maye And The Crowns — “Please Gospel Groups 78’s Foolish Things Remind Me Of You/Don’t STOCK MB $25 Don’t Leave Me/Do The Bop” R P M 438 M- Leave” FEDERAL 12129 M- MB $20 60. -

45 Inventory

45 Inventory item type artist title condition price quantity 45RPM ? And the Mysterians 96 Tears / Midnight Hour VG+ 8.95 222 45RPM ? And the Mysterians I Need Somebody / "8" Teen vg++ 18.95 111 45RPM ? And the Mysterians Cryin' Time / I've Got A Tiger By The Tail vg+ 19.95 111 45RPM ? And the Mysterians Everyday I have to cry / Ain't Got No Home VG+ 8.95 111 Don't Squeeze Me Like Toothpaste / People In 10 C.C. 45 RPM Love VG+ 12.95 111 45 RPM 10 C.C. How Dare You / I'm Mandy Fly Me VG+ 12.95 111 45 RPM 10 C.C. Ravel's Bolero / Long Version VG+ 28.95 111 45 RPM 100% Whole Wheat Queen Of The Pizza Parlour / She's No Fool VG+ 12 111 EP:45RP Going To The River / Goin Home / Every Night 101 Strings MMM About / Please Don't Leave VG+ 56 111 101 Strings Orchestra Love At First Sight (Je T'Aime..Moi Nom Plus) 45 RPM VG+ 45.95 111 45RPM 95 South Whoot (There It Is) VG+ 26 111 A Flock of Seagulls Committed / Wishing ( If I had a photograph of you 45RPM nm 16 111 45RPM A Flock of Seagulls Mr. Wonderful / Crazy in the Heart nm 32.95 111 A.Noto / Bob Henderson A Thrill / Inst. Sax Solo A Thrill 45RPM VG+ 12.95 555 45RPM Abba Rock Me / Fernando VG+ 12.95 111 45RPM Abba Voulez-Vous / Same VG+ 16 111 PictureSle Abba Take A Chance On Me / I'M A Marionette eve45 VG+ 16 111 45RPM Abbot,Gregory Wait Until Tomorrow / Shake You Down VG+ 12.95 111 45RPM Abc When Smokey Sings / Be Near Me VG+ 12.95 111 45RPM ABC When Smokey Sings / Be Near Me VG+ 8.95 111 45RPM ABC Reconsider Me / Harper Valley p.t.a. -

Download Submission Package

HARSTAD / Max, Mischa & The Tet Offensive “Sometimes I think if David Foster Wallace had finally been able to write the novel he'd dreamed of, it would read something like Max, Mischa & The Tet Offensive. It's a sprawling novel of ideas and information and pop culture, but it is also a love story folded into a tale of political change. What a big gulp of history Harstad takes on, and brilliantly shows what it feels like to live through – the unseparateness of it. The eerie feeling of inevitability giving way to a new reality frame. This is also one of the best family dramas I've read in some time, because it remembers that a story is essential to family life. Who are we and what are we for? Harstad asks this question of his cast so many different ways the novel begins to feel, in its sprawling uncertain outcome, like it has the grainy flicker of life itself.” – JOHN FREEMAN (author/editor/critic) – 2 HARSTAD / Max, Mischa & The Tet Offensive "There are many ways to say this, but this is probably the simplest: Max, Mischa & The Tet Offensive is a great novel." – JO NESBØ (Author) – 3 HARSTAD / Max, Mischa & The Tet Offensive – Table of contents – Praise for MAX, MISCHA & THE TET OFFENSIVE ................................ 5 Foreign sales of novel ...................................................................... 6 Overview of novel.............................................................................. 7 Novel’s table of contents .................................................................. 8 Synopsis & samples pages ............................................................... -

American Square Dance Vol. 36, No. 7

75Z. L--/Adi It JULY 1981 k AMC Zs- P col rIMERICAN 441116 iINFAt= Sprjra Cony 0.00 Annual $9.00 . ggunR.E..D.RNM DIAFF OWE a. 111' a. .r3in nr, ..... „,,. ,...:„. -r-r ( 1,11 41.: • rh""N .•••••••• •••••••••••••••• • • • • • • • • •••• .••••••••••••••e ••. •••••••• •••••••• ••••• ••••••••.•••••••••”• •••••••••"••••••••• •••••••• • • AMM ald"...11 Min Meet THE BOSS by &expo Power enough for 100 squares— twice the power of our previous models, yet small and lightweight for quick, convenient portability. Exceptional Reliability— 474):1 4110 proven In years of square dance use. A $1,000. Value— but priced at just $635.! Why the P-400 Is the Finest Professional Sound System Available This 17-pound system, housed In a 14"x14"x5" sewn vinyl carrying is easy to transport and set up, yet will deliver an effortless 120 R.M.S. watts of clear, clean power. Conservative design which lets the equipment "loarresults in high reliability and long life. Yet this small powerhouse has more useful features than we have ever offered before: VU meter for convenient visual sound level indication Two separate power amplifiers Two separately adjustable microphone channels Optional remote music control 5-gram stylus pressure for extended record life (Others use up to 10!) Internal strobe BUILT-IN music-only monitor power amplifier Tape Input and output Convenient control panel Exclusive Clinton Features Only Clinton has a floating pickup/turntable suspension, so that an accidental bump as you reach for a control knob will not cause needle skip. Only Clinton equipment can be operated on an inverter, on high line voltage, or under conditions of output overload without damage.