Century Planned New Towns and Villages Duncan Macintosh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renfrewshire Case Study Harnessing Renfrewshire’S Watery Wealth Overview Who? Renfrewshire Council

Renfrewshire Case Study Harnessing Renfrewshire’s Watery Wealth Overview Who? Renfrewshire Council. What? Two hydro projects, a hydro and district heating strategy, and an ambitious plan to grow willow coppices as biomass fuel on derelict industrial sites. Where? Paisley, Lochwinnoch, Renfrewshire How much? £76, 780 (development grants in total). Background Water powered the industrial revolution in Renfrewshire – and it’s now making a comeback as part of ambitious plans to beat fuel poverty. The local The council is now conducting a feasibility study to authority is using almost £20,000 of grant money from see if they can harness the water at the weir to drive a the Warm Homes Fund to explore two potential small- turbine which would supply some of the power used at scale hydro sites for electrical power generation – one Renfrewshire House, where the majority of the council’s in the centre of one of Scotland’s largest towns and the staff are based. Money generated from Feed In Tariffs other near a pretty rural village. could then be used to create a community benefits fund to provide affordable warmth to households. Also on the cards is a forward-thinking scheme to grow willow trees on derelict industrial land around the region, then use the wood to fuel biomass boilers at council buildings, as well as selling any excess on the burgeoning “ At the moment we have several schemes renewable energy market. on the go using Warm Homes Fund money, which has been wonderfully easy to access.” Renfrewshire had hundreds of water-powered mills in the 18th century – they ran the textiles industry which Ron Mould, Energy Officer (Housing), Renfrewshire Council saw Paisley pattern cloth exported across the world. -

Wed 12 May 2021

Renfrewshire Golf Union - Wed 12 May 2021 County Seniors Championship - Kilmacolm Time Player 1 Club CDH Player 2 Club CDH Player 3 Club CDH 08:00 Graham McGee Kilmacolm 4000780479 James Hope Erskine 4000783929 Keith Stevenson Paisley 4000988235 08:09 Richard Wilkes Cochrane Castle 4000782540 Brian Kinnear Erskine 4000781599 Iain MacPherson Paisley 4000986701 08:18 Bruce Millar Cochrane Castle 4001363171 Keith Hunter Cochrane Castle 4002416751 John Jack Gourock 4001143810 08:27 Morton Milne Old Course Ranfurly 4001317614 Alistair MacIlvar Old Course Ranfurly 4001318753 Stephen Woodhouse Kilmacolm 4002182296 08:36 Gregor Wood Erskine 4002996989 James fraser Paisley 4000986124 Mark Reuben Kilmacolm 4000973292 08:45 Iain White Elderslie 4000874290 Patrick McCaughey Elderslie 4001567809 Gerry O'Donoghue Kilmacolm 4001584944 08:54 Steven Smith Paisley 4000983616 Garry Muir Paisley 4000987488 David Pearson Greenock Whinhill 4002044829 09:03 Nairn Blair Elderslie 4003056142 Alex Roy Greenock 4001890868 Mitchell Ogilby Greenock Whinhill 4002044801 09:12 Brian Fitzpatrick Greenock 4002046021 William Boyland Kilmacolm 4001584434 Peter McFadyen Greenock Whinhill 4002225289 09:21 James Paterson Ranfurly Castle 4001000546 Ian Walker Elderslie 1000125227 Matthew McCorkell Greenock Whinhill 4002044608 09:30 Chris McGarrity Paisley 4000987044 Michael Mcgrenaghan Cochrane castle 4001795367 Archie Gibb Paisley 4000986153 09:39 Ian Pearston Cochrane Castle 4001795691 Patrick Tinney Greenock 4001890490 Les Pirie Kilmacolm 4002065824 09:48 Billy Anderson -

Notice of Meeting and Agenda Houston, Crosslee, Linwood, Riverside and Erskine Local Area Committee

Notice of Meeting and Agenda Houston, Crosslee, Linwood, Riverside and Erskine Local Area Committee Date Time Venue Wednesday, 14 June 2017 18:00 Gryffe High School, Old Bridge of Weir Rd, Houston PA6 7EB, KENNETH GRAHAM Head of Corporate Governance Membership Councillor Tom Begg: Councillor Audrey Doig: Councillor Alison Jean Dowling: Councillor Jim Harte: Councillor Scott Kerr: Councillor James MacLaren: Councillor Colin McCulloch: Councillor Iain Nicolson: Councillor James Sheridan: Councillor Natalie Don (Convener): Councillor Michelle Campbell (Depute Convener): Further Information This is a meeting which is open to members of the public. A copy of the agenda and reports for this meeting will be available for inspection prior to the meeting at the Customer Service Centre, Renfrewshire House, Cotton Street, Paisley and online at www.renfrewshire.cmis.uk.com/renfrewshire/CouncilandBoards.aspx For further information, please either email [email protected] or telephone 0141 618 7112. Members of the Press and Public Members of the press and public wishing to attend the meeting should report to the main reception at Gryffe High School where they will be met and directed to the meeting. 07/06/2017 Page 1 of 226 Items of business Apologies Apologies from members. Declarations of Interest Members are asked to declare an interest in any item(s) on the agenda and to provide a brief explanation of the nature of the interest. 1 Community Safety and Public Protection Update 3 - 12 Report by Director of Community Resources. 2 Street Stuff Annual Report 13 - 20 Report by Director of Community Resources. 3 Open Session/ Key Local Issues Senior Committee Services Officer (LACs) to report. -

Ayrshire & Galloway

ARCH.,EOLOGICAL H ISTORICAL COLLtrCTIONS RELATING TO AYRSHIRE & GALLOWAY VOL. VII. EDINBURGH PRINTED FOR THE AYRSHIRE AND GALLOWAY ARCH.€OLOGICAL ASSOCIATION MDCCCXCIV !a't'j j..l I Pt'inted 6y Ii. €s" Il. Clarlt !'ott DAVID DOUGLAS, EDINBURGII 300 Copies lriruted, Of zu/aiclo tlais is Uo. 7, f ( AYRSHIRE AND GALLOUIAY ARCH.TOtOGICAL ASSOCIATION {D re 5itr e nt. Tnn EARL or STAIR, K.T., LL.D., LP.S.A. Scot., Iord.-Lieutenant of Ayrshire and Wigtonshire. zrlitv--ptviiU sntE, Tirn DUKE or PORTLAND. Tnn MARQUESS or BUTE, K.'I., LL.D., F;S.A. Scot. Tnn MARQUESS ol AILSA, F.S.A. Scot. Tun EARL ol GALLOWAY, K.T. Tltn EARL or GLASGOW. THs LORD HERRIES, Lord-Lieutenant of the Stewartry. Tnn Rr. HoN. SrnJAS. FERGUSSON, B.Enr.,M.P.,G.C.S.I.,K.C.M.G.,C.I.E., LL.D. Tun Rrcnr Hos. Srn J. DALRYMPLE -HAY, Bart., C.8., D.C.L., F.R.S. Srn M. SHAW-STEWART, BAnt., Lord-Lieutenant of Renfrewshire. Sm IMILLIAM J. MOI{TGOMERY-CUNINGIIAME, Banr., Y.C., bf Corsehill. Sm HERBERT EUSTACE MAXWELL, Banr., of Monreith, M.P., F.S.A. Scot. R. A. OSWALD, Esq., of Auchincui've. ilron- Secretsries tor Tvrsbite, R. \ry. COCHRAN-PATRICK, Esq., of Woodsicle, LL.D., F.S.A., F.S.A. Scot. Tsn Hon. HEW DALRYMPLE, tr'.S,A. Scot. (for Carrick). J. SHEDDEN-DOBIE, Est1., of Morishill, F.S.A. Scot (for Cuningharne). R. MUNRO, Esc1., ILD., M.A., F.S.A. Scot. bgn, Setretarieg for fuN,igtsnsbit.e, Tqn Rnv. -

Information Bulletin March 2019

INFORMATION BULLETIN MARCH 2019 CONTENTS Service Page No. Environment and Infrastructure Road and Footways Capital Investment Programme 1 - 8 Financial Year 2019/20 Communities, Housing & Planning Services Notices and Licences Issued: 14 November 2018 to 9 - 18 18 February 2019 Delegated Items, Appeals and Building Warrants: 19 - 76 10 December 2018 to 15 February 2019 Finance & Resources Delegated Licensing Applications: 16 January to 77 - 89 31 January 2019 1 of 89 To: INFORMATION BULLETIN On: MARCH 2019 Report by: DIRECTOR OF ENVIRONMENT & INFRASTRUCTURE Heading: ROAD & FOOTWAYS CAPITAL INVESTMENT PROGRAMME, FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 1. Summary 1.1 At the Council meeting of 28 February 2019, it was agreed to deliver a £40milion, five-year investment in Renfrewshire roads, cycling routes and pedestrian paths, representing the biggest ever investment of its kind. This will make journeys safer and easier, improve business connectivity, support development and town centre improvements and make it easier for visitors to enjoy Renfrewshire attractions. 1.2 The approach during 2019/20 will continue the progressive improvement of roads assets and fits with the asset management approach of seeking to reduce reactive revenue expenditure through prudent life cycle investment. 1.3 The focus for 2019/20 includes schemes within the strategic road network as well as roads of local significance with a presence in every town and village across Renfrewshire. A sustained effort will continue to ensure the highest quality of product will be used and contractors’ standards will be robustly monitored throughout the year. 1.4 There are a number of strategic roads where works are planned and as such, detailed communication plans will be developed for each of these to ensure stakeholder engagement is maintained going forward. -

901, 904 906, 907

901, 904, 906 907, 908 from 26 March 2012 901, 904 906, 907 908 GLASGOW INVERKIP BRAEHEAD WEMYSS BAY PAISLEY HOWWOOD GREENOCK BEITH PORT GLASGOW KILBIRNIE GOUROCK LARGS DUNOON www.mcgillsbuses.co.uk Dunoon - Largs - Gourock - Greenock - Glasgow 901 906 907 908 1 MONDAY TO SATURDAY Code NS SO NS SO NS NS SO NS SO NS SO NS SO NS SO Service No. 901 901 907 907 906 901 901 906X 906 906 906 907 907 906 901 901 906 908 906 901 906 Sandbank 06.00 06.55 Dunoon Town 06.20 07.15 07.15 Largs, Scheme – 07.00 – – Largs, Main St – 07.00 07.13 07.15 07.30 – – 07.45 07.55 07.55 08.15 08.34 08.50 09.00 09.20 Wemyss Bay – 07.15 07.27 07.28 07.45 – – 08.00 08.10 08.10 08.30 08.49 09.05 09.15 09.35 Inverkip, Main St – 07.20 – 07.33 – – – – 08.15 08.15 – 08.54 – 09.20 – McInroy’s Point 06.10 06.10 06.53 06.53 – 07.24 07.24 – – – 07.53 07.53 – 08.24 08.24 – 09.04 – 09.29 – Gourock, Pierhead 06.15 06.15 07.00 07.00 – 07.30 07.30 – – – 08.00 08.00 – 08.32 08.32 – 09.11 – 09.35 – Greenock, Kilblain St 06.24 06.24 07.10 07.10 07.35 07.40 07.40 07.47 07.48 08.05 08.10 08.10 08.20 08.44 08.44 08.50 09.21 09.25 09.45 09.55 Greenock, Kilblain St 06.24 06.24 07.12 07.12 07.40 07.40 07.40 07.48 07.50 – 08.10 08.12 08.12 08.25 08.45 08.45 08.55 09.23 09.30 09.45 10.00 Port Glasgow 06.33 06.33 07.22 07.22 07.50 07.50 07.50 – 08.00 – 08.20 08.22 08.22 08.37 08.57 08.57 09.07 09.35 09.42 09.57 10.12 Coronation Park – – – – – – – 07.58 – – – – – – – – – – – – – Paisley, Renfrew Rd – 06.48 – – – – 08.08 – 08.18 – 08.38 – – 08.55 – 09.15 09.25 – 10.00 10.15 10.30 Braehead – – – 07.43 – – – – – – – – 08.47 – – – – 09.59 – – – Glasgow, Bothwell St 07.00 07.04 07.55 07.57 08.21 08.21 08.26 08.29 08.36 – 08.56 08.55 09.03 09.13 09.28 09.33 09.43 10.15 10.18 10.33 10.48 Buchanan Bus Stat 07.07 07.11 08.05 08.04 08.31 08.31 08.36 08.39 08.46 – 09.06 09.05 09.13 09.23 09.38 09.43 09.53 10.25 10.28 10.43 10.58 CODE: NS - This journey does not operate on Saturdays. -

Table 1: Mid-2008 Population Estimates - Localities in Alphabetical Order

Table 1: Mid-2008 Population Estimates - Localities in alphabetical order 2008 Population Locality Settlement Council Area Estimate Aberchirder Aberchirder Aberdeenshire 1,230 Aberdeen Aberdeen, Settlement of Aberdeen City 183,030 Aberdour Aberdour Fife 1,700 Aberfeldy Aberfeldy Perth & Kinross 1,930 Aberfoyle Aberfoyle Stirling 830 Aberlady Aberlady East Lothian 1,120 Aberlour Aberlour Moray 890 Abernethy Abernethy Perth & Kinross 1,430 Aboyne Aboyne Aberdeenshire 2,270 Addiebrownhill Stoneyburn, Settlement of West Lothian 1,460 Airdrie Glasgow, Settlement of North Lanarkshire 35,500 Airth Airth Falkirk 1,660 Alexandria Dumbarton, Settlement of West Dunbartonshire 13,210 Alford Alford Aberdeenshire 2,190 Allanton Allanton North Lanarkshire 1,260 Alloa Alloa, Settlement of Clackmannanshire 20,040 Almondbank Almondbank Perth & Kinross 1,270 Alness Alness Highland 5,340 Alva Alva Clackmannanshire 4,890 Alyth Alyth Perth & Kinross 2,390 Annan Annan Dumfries & Galloway 8,450 Annbank Annbank South Ayrshire 870 Anstruther Anstruther, Settlement of Fife 3,630 Arbroath Arbroath Angus 22,110 Ardersier Ardersier Highland 1,020 Ardrishaig Ardrishaig Argyll & Bute 1,310 Ardrossan Ardrossan, Settlement of North Ayrshire 10,620 Armadale Armadale West Lothian 11,410 Ashgill Larkhall, Settlement of South Lanarkshire 1,360 Auchinleck Auchinleck East Ayrshire 3,720 Auchinloch Kirkintilloch, Settlement of North Lanarkshire 770 Auchterarder Auchterarder Perth & Kinross 4,610 Auchtermuchty Auchtermuchty Fife 2,100 Auldearn Auldearn Highland 550 Aviemore Aviemore -

Renfrewshire Council Applications Decided by Head of Planning & Housing Under Delegated Powers During the Period

RENFREWSHIRE COUNCIL APPLICATIONS DECIDED BY HEAD OF PLANNING & HOUSING UNDER DELEGATED POWERS DURING THE PERIOD 03/05/2019 to 17/05/2019 Page 1 Applic no. Applicant Site Address Decision Decision Date 19/0124/PP Mr Asgah 39 Hairst Street, Renfrew, GRANT subject to 09/05/2019 39 Hairst Street PA4 8QU conditions 1 - Renfrew North Renfrew and Braehead PA4 8QU Proposal Change of use from Retail (Class 1) to hot food takeaway 19/0133/PP Trust Inns Limited Davidson's Public House, GRANT subject to 09/05/2019 Blenheim House Blenheim Hairst Street, Renfrew, conditions 1 - Renfrew North House PA4 8QU and Braehead Foxhole Road, Ackhurst Park, Chorley PR7 1NY Proposal Change of use from public footway to outdoor seating area 19/0243/PP Braehead Glasgow Limited Braehead Shopping GRANT 10/05/2019 40 Broadway Centre, King's Inch Road, 1 - Renfrew North London Renfrew, Glasgow, G51 and Braehead SW1H 0BU 4BS Proposal Installation of replacement plant equipment, related steelwork platform and screening at roof level 19/0234/CL Ms McFarlane 12 Atholl Crescent, GRANT 10/05/2019 12 Atholl Crescent Paisley, PA1 3AP 3 - Paisley Paisley Northeast and Ralston PA1 3AP Proposal Erection of single storey extension and decking to the rear of dwellinghouse 19/0260/CL Mr Sigley 51 Penilee Road, Paisley, GRANT 13/05/2019 51 Penilee Road PA1 3HE 3 - Paisley Paisley Northeast and PA1 3HE Ralston Proposal Erection of single storey extension to rear and side of dwellinghouse 19/0056/PP Trust Inns Old Swan Inn, 20 GRANT subject to 06/05/2019 Blenheim House Ackhurst Smithhills Street, Paisley, conditions 5 - Paisley East Park PA1 1EB and Central Fox Hall Road Chorley PR7 1NY Proposal Replacement windows to front elevation of public house. -

Intimations Surnames L

Intimations Extracted from the Watt Library index of family history notices as published in Inverclyde newspapers between 1800 and 1918. Surnames L This index is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted on microfiche, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Records are indexed by type: birth, death and marriage, then by surname, year in chronological order. Marriage records are listed by the surnames (in alphabetical order), of the spouses and the year. The copyright in this index is owned by Inverclyde Libraries, Museums and Archives to whom application should be made if you wish to use the index for any commercial purpose. It is made available for non- commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License). This document is also available in Open Document Format. Surnames L Record Surname When First Name Entry Type Marriage L’AMY / SCOTT 1863 Sylvester L’Amy, London, to Margaret Sinclair, 2nd daughter of John Scott, Finnart, Greenock, at St George’s, London on 6th May 1863.. see Margaret S. (Greenock Advertiser 9.5.1863) Marriage LACHLAN / 1891 Alexander McLeod to Lizzie, youngest daughter of late MCLEOD James Lachlan, at Arcade Hall, Greenock on 5th February 1891 (Greenock Telegraph 09.02.1891) Marriage LACHLAN / SLATER 1882 Peter, eldest son of John Slater, blacksmith to Mary, youngest daughter of William Lachlan formerly of Port Glasgow at 9 Plantation Place, Port Glasgow on 21.04.1882. (Greenock Telegraph 24.04.1882) see Mary L Death LACZUISKY 1869 Maximillian Maximillian Laczuisky died at 5 Clarence Street, Greenock on 26th December 1869. -

Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt

Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt HlUm'uiVi^mryTUFTS ii'S^Slt 024 287 G7 J83 Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt Records of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt COMPILED BY " TANTIVY » Author of " Scottish Hunts," and Contributor of Special Articles to "The Glasgow Herald" 1921 GLASGOW: PRINTED BY AIRD & COGHILL, LTD. PREFACE. ACTING upon the suggestion of the retiring Master and other prominent members of the Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt, I have ventured to produce an historical record which it is hoped will meet with the appreciation of those interested. For the description of the sport of the past twenty seasons I am greatly indebted to the diaries so perfectly kept by the late Mr. J. J. Barclay, which were kindly placed at my disposal by Mr. G. Barclay. Without such a valuable asset no work of this kind could ever have been attempted, and I have made the fullest possible use of these records, so that sportsmen and sportswomen of the last quarter of a century can refresh their memory in regard to the many great runs enjoyed during that period. I hope I have succeeded in an effort to furnish a complete and unvarnished account of the doings of the pack, together with a history of the Hunt since its origin. Possibly, at some future time, another enthusiast will take up the pen and bring the records up to date. Harry Judd (" Tantivy "). CONTENTS. PAGE The Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt, -------- 9 Group of Hounds in Kennel, 39 Presentation Ceremony at Finlaystone House, ------- 40 Meet at Barochan, -.-. -

Table 4 Localities in Descending Order of Size Locality 2004 Population

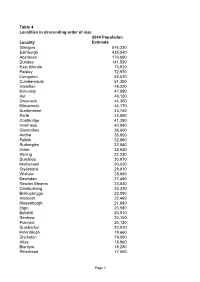

Table 4 Localities in descending order of size 2004 Population Locality Estimate Glasgow 575,330 Edinburgh 435,540 Aberdeen 176,690 Dundee 141,590 East Kilbride 73,820 Paisley 72,970 Livingston 53,670 Cumbernauld 51,300 Hamilton 48,220 Kirkcaldy 47,090 Ayr 46,120 Greenock 44,300 Kilmarnock 44,170 Dunfermline 43,760 Perth 43,590 Coatbridge 41,280 Inverness 40,880 Glenrothes 38,600 Airdrie 35,850 Falkirk 32,890 Rutherglen 32,840 Irvine 32,620 Stirling 32,230 Dumfries 30,970 Motherwell 30,520 Clydebank 29,610 Wishaw 28,840 Bearsden 27,460 Newton Mearns 23,530 Cambuslang 23,320 Bishopbriggs 23,080 Arbroath 22,460 Musselburgh 21,880 Elgin 20,580 Bellshill 20,510 Renfrew 20,150 Polmont 20,130 Dumbarton 20,070 Kirkintilloch 19,660 Clarkston 19,000 Alloa 18,960 Blantyre 18,280 Peterhead 17,560 Page 1 Localities in descending order of size 2004 Population Locality Estimate Stenhousemuir 17,300 Grangemouth 17,280 Barrhead 17,250 Kilwinning 16,320 Giffnock 16,190 Buckhaven 16,140 Viewpark 15,780 Port Glasgow 15,760 Johnstone 15,710 Bathgate 15,650 Larkhall 15,560 Erskine 15,550 St Andrews 15,200 Prestwick 14,800 Troon 14,430 Helensburgh 14,410 Penicuik 14,320 Bonnyrigg 14,250 Bo'ness 14,240 Hawick 14,210 Galashiels 13,960 Broxburn 13,630 Carluke 13,590 Alexandria 13,480 Forfar 13,150 Linlithgow 13,130 Mayfield 12,910 Milngavie 12,820 Rosyth 12,490 Fraserburgh 12,150 Cowdenbeath 11,720 Gourock 11,690 Saltcoats 11,560 Largs 11,360 Dalkeith 11,260 Whitburn 10,830 Montrose 10,790 Inverurie 10,760 Ardrossan 10,720 Stranraer 10,600 Carnoustie 10,260 Stonehaven -

To Let Roadside Retail Development 3 Units Pre-Let to Well Known National Operators

TO LET ROADSIDE RETAIL DEVELOPMENT 3 UNITS PRE-LET TO WELL KNOWN NATIONAL OPERATORS • Highly visible location on busy arterial road • New build development with dedicated parking • Particularly suited to convenience retailing • Only ONE unit remaining LOCATION M8 TO GREENOCK GLASGOW Paisley is Scotland’s largest town AND WEST AIRPORT and is located approximately M8 11 miles west of Glasgow City Centre. The town is estimated to J29 TO GLASGOW enjoy a primary retail catchment CITY CENTRE exceeding 170,000 persons. A737 A726 A741 LINWOOD PHOENIX RETAIL PARK A761 PAISLEY A761 A737 TOWN CENTRE A761 A761 A761 JOHNSTONE A726 A789 ELDERSLIE A761 FERGUSLIE EXIT ENTRANCE 25 CAR PARKING SPACES DELIVERY LET TO: TO LET LET TO: LET TO: LET TO: LANE SITUATION INDIGO UNIT 4 THE GREGGS DOMINO’S SUN 1,200 SQ FT CHIPPY The development is ideally situated on the outbound side BIN of the A761, approximately 2 miles west of Paisley Town STORE Centre, en route to the Phoenix Retail and Leisure Parks at Linwood, and popular residential areas of Johnstone, Elderslie, Kilbarchan and Lochwinnoch. DESCRIPTION ACCOMMODATION The subjects comprise a new 5 unit single storey parade built to Units will be finished to standard developers modern specifications with dedicated parking, enjoying extensive shell specification, details upon application. frontage to the A761 Ferguslie. A mixture of Class 1, 2 and 3 uses is permitted. UNIT SQ FT SQ M AVAILABILITY 1 1,500 139.35 Domino’s 2 1,200 111.48 Greggs 3 1,000 92.90 The Chippy 4 1,200 111.48 Available 5 1,250 116.13 Indigo Sun FRONT ELEVATION TERMS ENTRY The remaining shop is offered on modern FRI terms Target date of entry March 2019 upon conclusion of with provision for 5 yearly rent reviews; rent upon all legal formalities.