Residentsâ•Ž Perceptions of the 2010 FIFA World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 3132 2 No

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA Vol. 665 Pretoria, 13 November 2020 No. 3132 2 No. 3132 GOVERNMENT TENDER BULLETIN, 13 NOVEMBER 2020 GOVERNMENT TENDER BULLETIN, 13 NOVEMBER 2020 NO.3132 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS TENDER INVITED FOR SUPPLIES, SERVICES AND DISPOSALS ............................................................. 16 SUPPLIES: GENERAL ......................................................................................................................................... 16 SUPPLIES: COMPUTER EQUiPMENT................................................................................................................ 24 SUPPLIES: ELECTRICAL EQUIPMENT .............................................................................................................. 26 SUPPLIES: MEDiCAL........................................................................................................................................... 27 SUPPLIES: PERISHABLE PROViSiONS............................................................................................................. 30 SUPPLIES: STATIONERY/PRINTING .................................................................................................................. 30 SERVICES: GENERAL......................................................................................................................................... 31 SERVICES: BUILDING ......................................................................................................................................... 46 SERVICES: CIVIL ................................................................................................................................................ -

2010 Fifa World Cup Fan Guide

FAN GUIDE Publishing Credits Publisher The 2010 FIFA World Cup Organising Committee South Africa SAFA House, 76 Nasrec Road, Nasrec Ext 3, 2190 Gauteng, South Africa Private Bag X 2010, Mondeor 2110 Johannesburg, South Africa Responsible for content: The 2010 FIFA World Cup Organising Committee South Africa FIFA With thanks to: www.southafrica.info SA Tourism The GCIS Layout and design: Carol Cole Advertising & Design www .carolcole.co.za email: [email protected] Images: The 2010 FIFA World Cup Organising Committee South Africa TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Welcome from the 2010 FIFA World Cup Organising Committee South Africa 2 2. Hello from the Official Mascot of the 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa ™ 3 3. Host country information 5 4. The 2010 FIFA World Cup™ host cities and stadiums 9 5. The 2010 FIFA World Cup Fan Fest™ 53 6. Zakumi’s price index 65 7. Learn to speak South African 66 8. Getting around 70 9. Where to stay 78 10. Keeping safe 81 11. Keeping healthy 84 12. Keeping in touch 86 13. Important contact numbers and e-mail addresses IBC Dear friends of football Let us take this opportunity to welcome you to this continent, and more specifically to its southern most tip, the host of the 2010 FIFA World Cup™, South Africa. Over the next few months you will get to know and experience the many things which make South Africa one of the most unique places in the world. You will find our people hospitable, our food delicious, our views spectacular, our weather inviting and our culture intriguing. -

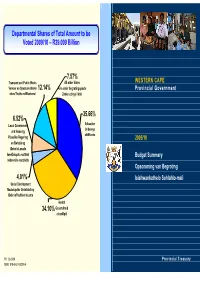

Departmental Shares of Total Amount to Be Voted 2009/10 – R29.009 Billion

Departmental Shares of Total Amount to be Voted 2009/10 – R29.009 Billion 7.57% Transport and Public Works All other Votes WESTERN CAPE Vervoer en Openbare Werke 12.14% Alle ander begrotingsposte Provincial Government elezo Thutho neMisebenzi Zonke ezinye iiVoti 35.66% 6.52% Local Government Education and Housing Onderwys eleMfundo Plaaslike Regering 2009/10 en Behuising iSebe loLawulo lweeDolophu neZithili Budget Summary nobonelelo ngezindlu Opsomming van Begroting 4.01% Isishwankathelo Sohlahlo-mali Social Development Maatskaplike Ontwikkeling iSebe loPhuhliso loLuntu Health Gesondheid 34.10% elezeMpili PR: 03/2009 Provincial Treasury ISBN: 978-0-621-38390-4 Ukukhusela nokuphakamisa umgangatho weenkqubo zokujongana nolutsha, abasetyhini, abakhulileyo 2009/10 Budget Summary nabahlwempuzekileyo Ukuphuculwa kofikeleleko lweenkonzo zentlalo ngabo basemngciphekweni kusoloko kuyeyona nto iphambili kwiSebe loPhuhliso The impetus of this budget is to support labour-intensive services and lwezeNtlalo yoLuntu, lona lifumene isigidigidi esi-R1.163 kunyaka-mali wama-2009/10. Eyona miba iphambili ekujoliswe kuyo yileyo infrastructure programmes that raise the long-term growth potential of the yokubonelela ngamaziko okusebenza ukusetyenziswa gwenxa kwezinxilisi (kugxininiswe kusetyenziso lweziyobisi, ukusetyenziswa economy and facilitate higher exports (including the prioritisation of maintenance gwenza kotywala,,uthintelo, unyango novuselelo) nokubonelela ngeendawo ezikhuselekileyo zokuhlalisa abantwana. Ngaphezu koko, ukugxininisa ekukhuseleni -

Vote 10 : Transport and Public Works

Vote 10 Department of Transport and Public Works 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 To be appropriated MTEF allocations R3 686 548 000 R3 800 202 000 R3 975 298 000 Responsible MEC Provincial Minister of Transport and Public Works Administering Department Department of Transport and Public Works Accounting Officer Head of Department, Transport and Public Works 1. Overview Core functions and responsibilities To lead the provincial strategic objective of increasing access to safe and efficient transport. To support other provincial strategic objectives through interventions related to provincial infrastructure and property management and the co-ordination of the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) within the Western Cape. To conduct the overall management and administrative support of the department, as well as the respective programmes within the department in accordance with the Public Service Act, 1994, the Public Finance Management Act, 1999 (as amended), and other applicable legislation. To utilise the Expanded Public Works Programme as one of the methods to deliver the services described below and to contribute to skills development and the fight against poverty. To plan, regulate and facilitate the provision of accommodation for client departments and related entities; manage the provincial property portfolio for the optimum benefit of all concerned; render professional, technical and implementing agent services in respect of buildings and other related infrastructure and facilitate infrastructure planning in the Province of the Western Cape. To promote accessibility and the safe, affordable movement of people, goods and services through the delivery and maintenance of roads infrastructure that is sustainable, integrated and environmentally sensitive, and which supports and facilitates social and economic growth through socially just, developmental and empowering processes. -

Provincial Gazette Extraordinary

PROVINSIE WES-KAAP PROVINCE OF THE WESTERN CAPE IPHONDO LENTSHONA KOLONI Provincial Gazette Extraordinary 6500 Friday, 15 February 2008 Registered at the Post Offıce as a Newspaper WHITE PAPER THE IKAPA GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY (IKAPA GDS) WHICH SERVES AS A WHITE PAPER FOR THE WESTERN CAPE WITSKRIF DIE IKAPA- GROEI- EN ONTWIKKELINGSTRATEGIE (IKAPA-GOS) WAT DIEN AS ’N WITSKRIF VIR DIE WES-KAAP IPHEPHA LENGCACISO ISICWANGCISO-NKQUBO SOKUHLUMA KUNYE NOPHUHLISO (IKAPA GDS) ESISEBENZA NJENGEPHEPHA LENGCACISO KUSENZELWA INTSHONA KOLONI 2 Province of Western Cape: Provincial Gazette Extraordinary 6500 15 February 2008 iKapa Elihlumayo GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY DRAFT WHITE PAPER White Paper 15 February 2008 15 February 2008 Province of Western Cape: Provincial Gazette Extraordinary 6500 3 Published by: Provincial Government of the Western Cape Department of the Premier Directorate Communications, Conceptualisation and Research 7 Wale Street Cape Town Copyright 2007@Provincial Government Western Cape Copyrights subsist in this work. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written consent of the Provincial Government of the Western Cape. Any unauthorised reproduction of this work will constitute a copyright infringement. 4 Province of Western Cape: Provincial Gazette Extraordinary 6500 15 February 2008 FOREWORD The Western Cape Province is home to unrivalled natural beauty – founded in a rich tapestry of people and events that contributed to its historical heritage – and blessed with human, social and environmental resources that give this region a truly unique sense of place in the world. The Western Cape Province also, however, remains characterised by deep inequalities among its different peoples. -

Breakfast 23Sept09

Cape Town Stadium: a Catalyst for Uniting the City Dr Laurine Platzky 23 Sept 2009 2010 FIFA WORLD CUP™ HOST CITY: CAPE TOWN The Mandate Host City and Province OBJECTIVES Host semi-final and events successfully Maximise public benefit and lasting legacy: Infrastructure development Economic Opportunities Environmental legacy Social cohesion: ‘Home for All’ Desirable destination for investment, trade, tourism Geographic spread beyond City to rest of Western Cape Our 2010 World Cup Strategic Positioning 2010 World Cup Success C O L E L C M E P V O E G N L A I R T A C R A Y N G O C E L E Stakeholder Management 2010 Event in Cape Town Stadium Transport Accommodation Events/Logistics Safety Fan Fest Marketing & & Security Communications Airport 2010 FIFA WC CAPE TOWN Station Infrastructure Environmental & planning Convention Centre Economic Development Cape Tow n/W P Profile High Cape Town - leveraged Cape Town – Un P r o f i l e leveraged Low Low Econom ic/Developm ental Benefits High Building a Legacy Infrastructure Stadia Transport Financial Sufficient funds Social Legacy Partnerships Community revitalisation In Budget Tangible & Education and Culture Intangible Workforce Skills Benefits National Pride and Unity Environmental Beautification Going for the green Sports Legacy Participation Competitive Skills Commercialisation 2010 Project Integration: A transversal approach to governance Tourism, investment & film; economic dev; accommodation Environmental sustainability FIFA projects, events and marketing PM and COMMUNICATION ECONOMIC LEGACY -

2010 Fifa World Cup Host Cities

Host City Background Sheet Johannebsurg Fast Facts: Province: Gauteng Province Population: 3,2 million Altitude: 1753m Geography: Located on the eastern high-lying plateau in South Africa referred to as the Highveld. Climate: Dry with winter temperatures ranging from 24°-16°C. Summer is temperate with temperatures exceeding 30°C and afternoon thundershowers. Key Economic Sectors: Retail, Finance Professional Football Clubs: Bidvest Wits, Kaizer Chiefs, Moroka Swallows Orlando Pirates (Premier) FC AK, Jomo Cosmos (1st Division) GPS Coordinates: 26°12:16;S 28°2:44;E Did you know? • Johannesburg is one of the 40 largest metropolitan areas of the world. • Forty percent of the world's gold is found in the greater Johannesburg region. In effect, Johannesburg is also referred as ‘Egoli’, meaning the ‘Place of Gold’. • Around 1569 hectares of land is covered by nature reserves in the city of Johannesburg. • Johannesburg is laced with over 10 million trees, and therefore is also known as the largest man made forest in the world. The City: In Johannesburg, wining and dining is superb; the championship golf courses are of the highest standard; and there seems to be an ongoing party all day, every day. In addition, the city boasts beautiful natural surroundings, adventure sports and the world’s foremost palaeontological site at Sterkfontein. Jozi, Jo'burg or Egoli to its friends - the city is a vibrant melting pot of humanity that ensures you won’t walk alone when exploring the city’s many cultural and leisure attractions. The City of Gold welcomes you. The area where Johannesburg stands was once grassland, but is now one of the biggest man- made forests in the world. -

Western Cape 2009 Budget Overview

Provincial Government Western Cape Provincial Treasury BUDGET 2009 OVERVIEW PR: 02/2009 ISBN: 978-0-621-38389-8 To obtain additional information and/or copies of this document, please contact: Western Cape Provincial Treasury Directorate Budget Office Private Bag X9165 15 Wale Street Cape Town Tel: (021) 483-5618 Fax: (021) 483-6601 E-mail: [email protected] This publication is also available online at http://www.capegateway.gov.za/eng/pubs/budgets/ Printed in the Republic of South Africa For the Government Printers Cape by Formeset Printers Cape Foreword The 2009 Western Cape Provincial Budget reaffirms this Government’s commitment to finding ways to provide improved access to quality public, social and economic services despite the current challenging economic environment. Our strategic focus over the medium term remains unchanged, however periodic refinements have allowed for adjustments in key service delivery areas. The Provincial Budget represents the end result of a number of discussions, technical scrutiny, political interaction and determination of absolute and relative priorities. The 2009 Budget Overview therefore focuses on the major service delivery highlights of departments and provides valuable insights as to what the allocations over the 2009 MTEF are meant to buy. It focuses on some of the more pertinent achievements and makes the case that departmental allocations over the MTEF should be seen in context of already strong baseline growths. Budget 2009 is derived from our collective efforts to acknowledge community -

PCF Report: Overview of Provincial FWC 2010 Activities Dr Laurine

PCF Report: Overview of Provincial FWC 2010 Activities Dr Laurine Platzky FWC 2010 Western Cape Coordinator 27 July 2010 Cape Town & Western Cape Objectives Host semi-final and events successfully Maximum public benefit and lasting legacy Infrastructure development Economic opportunities Environmental responsibility Social cohesion Desirable destination for investment, trade & tourism Geographic spread beyond Host City to Province Have we succeeded? Social Legacy Football for Hope Centre Preliminary Draw Durban: announcement of 20 centres – Nov 2007 Official Launch – 5 Dec 2009 Africa Day Celebrations - Celebration of our African Teams participating in the World Cup – 29 May 2009 Using the power of football to address issues of tolerance and diversity among our youth Holiday Programme: 11 July 2010 visited by Queen Sophia of Spain Countdown Events – building ‘gees’ among internal (public servants) and external (the public) clients DAYS TO GO e.g. - 1000 days: Grand Parade Five-Aside tournament for disadvantaged youth - 500 days: Flying the Flag - One Year to Go: PGWC Inter-departmental “Best Dressed Fan” day - 100 days: planted 100 trees for 100 days: community gardeners at Philippi Stadium - 50 Days to Go: “Catch the Train” day with MEC Carlisle to promote public transport NATIONAL DAYS e.g. - Women’s Day 2009: 300 girls playing football and learning life skills for 300 days to kick-off - Freedom Day 2010: Topless Bus Tour “Fly the Flag” - Africa Day 2010: “Support all of Africa” youth tournament in Khayelitsha - 16 June 2010: Coaching Day with FIFA at Philippi Stadium - OTHER EVENTS e.g. - Final Draw Soiree (4 Dec 2009) - Launch of Football Friday at Philippi (30 October 2009) - Philippi Test and Opening event: Ajax Legends vs. -

2010 FIFA World Cup ™ Cape Town and the Western Cape

2010 FIFA World Cup ™ Cape Town and the Western Cape: Your host in 2010! Western Cape Premier: Ms Lynne Brown 7 February 2009 Cape Town and the Western Cape Contents 1. Objectives 2. Our readiness 3. Accessing the Cape 4. A place to stay 5. A place to train 6. A place for football 7. A place to celebrate 8. What’s on 9. Your kind assistance Cape Town & Western Cape 2010 Objectives Host semi-final and events successfully Maximum public benefit and lasting legacy Infrastructure development Economic Opportunities Environmental legacy Social cohesion: ‘Home for All’ Desirable destination for investment, trade, tourism Geographic spread beyond the City To Airport Cape Town International Convention Centre CT Station Central public viewing area Somerset Hospital V&A Waterfront Green Point Stadium Granger Bay Boulevard Our readiness for the 2010 FIFA World Cup We have heard your most frequently asked questions: Are we really going to be ready to host? How safe will my fans be? We will now focus on readiness SAPS will present the 2010 Safety Plan Stadium, forecourt and pedestrian underpass Stadium@ Green Point: 23 January 2009 Accessing the Cape Cape Town International Airport Upgrade • Connected by direct scheduled flights to major airports in Europe, South America, North America, Asia and Africa • Regular flight connections to leading cities in South Africa Cape Town Station Concourse Upgrade • Sophisticated road infrastructure • Extensive rail network • Visitors will move around by meter taxi, coach, train or on foot Cape Town International Airport Upgrade CTIA Departure Drop Off Area Cape Town Station Upgrade Hospital Bend Upgrade Road Upgrades: Hospital Bend Pre Selection Scheme •** AIRPORT CITY LINK: BMT LANE Airport City Link: BMT Lane: Inbound 1. -

2011 Western Cape Bi

PROVINCE OF THE WESTERN CAPE WESTERN CAPE APPROPRIATION BILL (As introduced) (MINISTER OF FINANCE AND ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES) [B 4—2021] PROVINSIE WES-KAAP WES-KAAPSE BEGROTINGSWETSONTWERP (Soos ingedien) (MINISTER VAN FINANSIES EN EKONOMIESE GELEENTHEDE) [W 4—2021] IPHONDO LENTSHONA KOLONI UMTHETHO OSAYILWAYO WOLWABIWO-MALI WENTSHONA KOLONI (Njengoko yzisiwe) (NGUMPHATHISWA WEZEMALI NAMATHUBA EZOQOQOSHO) [B 4—2021] ISBN 978-1-928393-73-3 No. of copies printed ....................................... 150 2 BILL To provide for the appropriation of money from the Provincial Revenue Fund for the requirements of the Province of the Western Cape in the 2021/22 financial year; and to provide for matters incidental thereto. E IT ENACTED by the Provincial Parliament of the Western Cape, as B follows:— Definitions 1. In this Act, unless the context indicates otherwise, a word or expression to which a meaning has been assigned in section 1 of the Public Finance Management Act, 1999 5 (Act 1 of 1999), has the meaning assigned to it in that Act, and— ‘‘conditional allocation’’ means an allocation due to a municipality as contem- plated in section 36(2) of the Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act; ‘‘current payments’’ means any payment made by a provincial department and 10 classified as or deemed to be a current payment in accordance with the guidelines and instructions on economic reporting formats issued by the National Treasury in terms of the Public Finance Management Act; ‘‘Division of Revenue Act’’ means the Division of Revenue Act, -

Launch of the Host City Cape Town Green Goal Legacy Report

SPEECH Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. CAPE TOWN PREMIER HELEN ZILLE July 13, 2011 Launch of the Host City Cape www.kas.de/southafrica Town Green Goal Legacy Report The spoken word shall prevail. cesses. Host City Cape Town exceeded the national targets for waste-to-landfill reduc- A year ago today, FIFA awarded South Af- tion and the use of public and non- rica “9 out of 10 - a summa cum laude with motorised transport by a large margin, sig- highest praise” for the country’s efforts in nificantly reducing the environmental im- hosting the 2010 FIFA World Cup™. South pact of the event. Throughout the World Africa became only the third host country Cup one of the important successes was the since 1930 to attract more than 3 million manner in which good waste management paying spectators; the showpiece was re- added to the general tourist appeal and fan sponsible for the word “vuvuzela” being en- experience. The Cape Town Stadium tered into the Oxford English Dictionary and achieved an estimated 15% saving in elec- the FIFA World Cup™ showcased South Af- tricity use and a 27% reduction in water rica and Host City Cape Town to the world use. Dual-flush toilets, low flow shower- in a way that no other event had done pre- heads and taps were installed, while spring viously. water from Oranjezicht on the slopes of Ta- ble Mountain irrigates the Green Point Ur- What the 2010 FIFA World Cup™ demon- ban Park, saving 580 million litres of drink- strated is that when South Africa’s decision ing water per year.