Latin America and the Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IOM Regional Strategy 2020-2024 South America

SOUTH AMERICA REGIONAL STRATEGY 2020–2024 IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Av. Santa Fe 1460, 5th floor C1060ABN Buenos Aires Argentina Tel.: +54 11 4813 3330 Email: [email protected] Website: https://robuenosaires.iom.int/ Cover photo: A Syrian family – beneficiaries of the “Syria Programme” – is welcomed by IOM staff at the Ezeiza International Airport in Buenos Aires. © IOM 2018 _____________________________________________ ISBN 978-92-9068-886-0 (PDF) © 2020 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. PUB2020/054/EL SOUTH AMERICA REGIONAL STRATEGY 2020–2024 FOREWORD In November 2019, the IOM Strategic Vision was presented to Member States. It reflects the Organization’s view of how it will need to develop over a five-year period, in order to effectively address complex challenges and seize the many opportunities migration offers to both migrants and society. It responds to new and emerging responsibilities – including membership in the United Nations and coordination of the United Nations Network on Migration – as we enter the Decade of Action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. -

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Declaration by the Heads of States and Governments of Belize, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama and Dominican R

DECLARATION BY THE HEADS OF STATES AND GOVERNMENTS OF BELIZE, COSTA RICA, GUATEMALA, HONDURAS, NICARAGUA, PANAMA AND DOMINICAN REPUBLIC FACING THE PANDEMIC OF COVID-19 CENTRO AMERICA ALLIED AGAINST CORONA VIRUS 12th, March, 2020 The Heads of States and Governments of Belize, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama and Dominican Republic having a extraordinary virtual session under the pro tempore Presidency of SICA, with Honduras in the charge. Considering That the World Health Organization, with globally alarming levels of spread and severity of cases by COVID-19, has declared this disease to be a pandemic. This implies the necessity of regional agreements on containment against its spread for the safety of our inhabitants. The Resolution COMISCA 01-2020 adopted during the Extraordinary Meeting of the Council of Ministers of Health of Central America and the Dominican Republic (COMISCA), held on 3rd of March, 2020, relative to the situation of threats of COVID-19, and the regional reaction in public health against the pandemic, where joint actions are established. That faced of the threats of COVID-19, the General Secretariat of SICA and the Executive Secretariat of COMISCA have made efforts to establish regional, intersectoral approach in response to the pandemic DECLARE 1. The importance given by the Governments of the member states of SICA for the tutelage and protection of the human security, public health and common good for population in th e region, mainly in view of the expansion of COVID-19, which requires adopting joint meas ures and coordination to face it. 2. To the nations of the region, that our national health systems attend to the pandemic acco rding to the protocols guided by the World Health Organization / Pan American Health Org anization (WHO / PAHO), taking national measures through the Ministries and Secretaries of Health, including binational and cross-border collaboration of health services for compre hensive care of suspected and confirmed cases of COVID-19 and other public health probl ems. -

South America Wine Cruise!

South America Wine Cruise! 17-Day Voyage Aboard Oceania Marina Santiago to Buenos Aires January 28 to February 14, 2022 Prepare to be awestruck by the magnificent wonders of South America! Sail through the stunning fjords of Patagonia and experience the cheerfully painted colonial buildings and cosmopolitan lifestyle of Uruguay and Argentina. Many people know about the fantastic Malbec, Torrontes, Tannat, and Carminiere wines that come from this area, but what they may not know is how many other great styles of wine are made by passionate winemakers throughout Latin America. This cruise will give you the chance to taste really remarkable wines from vineyards cooled by ocean breezes to those perched high in the snow-capped Andes. All made even more fun and educational by your wine host Paul Wagner! Your Exclusive Onboard Wine Experience Welcome Aboard Reception Four Exclusive Wine Paired Dinners Four Regional Wine Seminars Farewell Reception Paul Wagner Plus Enjoy: Renowned Wine Expert and Author Pre-paid Gratuities! (Expedia exclusive benefit!) "After many trips to Latin America, I want to share the wines, food and Complimentary Wine and Beer with lunch and dinner* culture of this wonderful part of the Finest cuisine at sea from Executive Chef Jacques Pépin world with you. The wines of these FREE Unlimited Internet (one per stateroom) countries are among the best in the Country club-casual ambiance world, and I look forward to Complimentary non-alcoholic beverages throughout the ship showing you how great they can be on this cruise.” *Ask how this can be upgraded to the All Inclusive Drink package onboard. -

Central America (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua): Patterns of Human Rights Violations

writenet is a network of researchers and writers on human rights, forced migration, ethnic and political conflict WRITENET writenet is the resource base of practical management (uk) independent analysis e-mail: [email protected] CENTRAL AMERICA (GUATEMALA, EL SALVADOR, HONDURAS, NICARAGUA): PATTERNS OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS A Writenet Report by Beatriz Manz (University of California, Berkeley) commissioned by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Status Determination and Protection Information Section (DIPS) August 2008 Caveat: Writenet papers are prepared mainly on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. The papers are not, and do not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Writenet or UNHCR. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ................................................................................ iii 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 1.1 Regional Historical Background ................................................................1 1.2 Regional Contemporary Background........................................................2 1.3 Contextualized Regional Gang Violence....................................................4 -

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

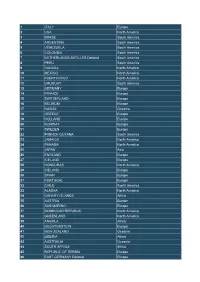

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

State and Economy in Nicaragua

E. V. K. FitzGerald role of the state and planning under the Sandinistas', A Mixed Economy in Transition he argues that other structural changes (such as land reform and public investment) 'may lead to a future One of the main features of Nicaragua since 1979 has situation in which the position of the state in the been theSandinista commitment toa 'mixed Nicaraguanpolitical economy can beradically economy' while retaining both political hegemony and transformed'. the monopoly of armed force. This concept is officially It is clearly too early, in historical terms at least, to seen as having three dimensions: the balance between evaluate the feasibility of the Sandinista model - state and private property in the corporate enterprise particularly in view of US attempts at economic and sector; the maintenance of a large petty commodity military destabilisation [ICJ 1986]but it is possible sector in almost all branches of the economy; and the to identify some key characteristics of the model and establishment of non-aligned international trading analyse its mutation since 1979. In this article, I shall relations [Miplan 1980; SPP 1987]. The apparently try to show how the relation between the state and the long-term character of this social construct makes market shifted in response to both war and economic Nicaragua distinct from many other experiences of the problems; how the basis of the planning system construction of socialism, although it is consistent changed from a 'dual economy' model to one based on with more recent reform initiatives [FitzGerald and the articulation of distinct forms of production; and Wuyts 1988]. -

Nicaragua's Constitution of 1987 with Amendments Through 2005

PDF generated: 19 Feb 2021, 13:07 constituteproject.org Nicaragua's Constitution of 1987 with Amendments through 2005 © Oxford University Press, Inc. Translated by Max Planck Institute Prepared for distribution on constituteproject.org with content generously provided by Oxford University Press. This document has been recompiled and reformatted using texts collected in Oxford’s Constitutions of the World. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 19 Feb 2021, 13:07 Table of contents Preamble . 3 TITLE I: FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES . 4 TITLE II: THE STATE . 5 TITLE III: NICARAGUAN NATIONALITY . 6 TITLE IV: RIGHTS, DUTIES AND GUARANTEES OF THE NICARAGUAN PEOPLE . 8 Chapter I: Individual Rights . 8 Chapter II: Political Rights . 13 Chapter III: Social Rights . 14 Chapter IV: Rights of the Family . 16 Chapter V: Labor Rights . 18 Chapter VI: Rights of the Communities of the Atlantic Coast . 19 TITLE V: NATIONAL DEFENSE . 20 TITLE VI: NATIONAL ECONOMY, LAND REFORM AND PUBLIC FINANCES . 21 Chapter I: National Economy . 21 Chapter II: Land Reform . 23 Chapter III: Of Public Finances . 24 TITLE VII: EDUCATION AND CULTURE . 25 TITLE VIII: THE ORGANIZATION OF THE STATE . 27 Chapter I: General Principles . 27 Chapter II: Legislative Branch . 28 Chapter III: Executive Branch . 36 Chapter IV: Of the Office of the Controller General of the Republic . 43 Chapter V: Judicial Branch . 44 Chapter VI: Electoral Branch . 47 TITLE IX: POLITICAL ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION . 49 Chapter I: Of Municipalities . 49 Chapter II: Communities of the Atlantic Coast . 51 TITLE X: SUPREMACY OF THE CONSTITUTION, ITS REFORM AND CONSTITUTIONAL LAWS . 52 Chapter I: Of the Political Constitution . 52 Chapter II: Constitutional Control . -

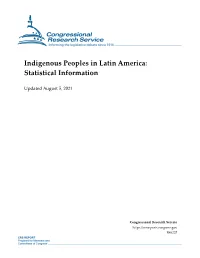

Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical Information

Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical Information Updated August 5, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46225 SUMMARY R46225 Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical August 5, 2021 Information Carla Y. Davis-Castro This report provides statistical information on Indigenous peoples in Latin America. Data and Research Librarian findings vary, sometimes greatly, on all topics covered in this report, including populations and languages, socioeconomic data, land and natural resources, human rights and international legal conventions. For example the figure below shows four estimates for the Indigenous population of Latin America ranging from 41.8 million to 53.4 million. The statistics vary depending on the source methodology, changes in national censuses, the number of countries covered, and the years examined. Indigenous Population and Percentage of General Population of Latin America Sources: Graphic created by CRS using the World Bank’s LAC Equity Lab with webpage last updated in July 2021; ECLAC and FILAC’s 2020 Los pueblos indígenas de América Latina - Abya Yala y la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible: tensiones y desafíos desde una perspectiva territorial; the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and World Bank’s (WB) 2015 Indigenous Latin America in the twenty-first century: the first decade; and ECLAC’s 2014 Guaranteeing Indigenous people’s rights in Latin America: Progress in the past decade and remaining challenges. Notes: The World Bank’s LAC Equity Lab -

SOUTH AMERICA July/August 2007 GGETTINGETTING SSTARTEDTARTED: Guide

SOUTH AMERICA July/August 2007 GGETTINGETTING SSTARTEDTARTED: Guide Is It Time for a ® South American Strategy? Localization Outsourcing ® and Export in Brazil Doing Business ® in Argentina The Tricky Business ® of Spanish Translation Training Translators ® in South America 0011 GGuideuide SSoAmerica.inddoAmerica.indd 1 66/27/07/27/07 44:13:40:13:40 PPMM SOUTH AMERICA Guide: GGETTINGETTING SSTARTEDTARTED Getting Started: Have you seen the maps where the Southern Hemisphere is at South America the top? “South-up” maps quite often are — incorrectly — referred to as “upside-down,” and it’s easy to be captivated by them. They Editor-in-Chief, Publisher Donna Parrish remind us in the Northern Hemisphere how region-centric we are. Managing Editor Laurel Wagers In this Guide to South America, we focus on doing business and work in Translation Department Editor Jim Healey South America. Greg Churilov and Florencia Paolillo address common trans- Copy Editor Cecilia Spence News Kendra Gray lation misconceptions in dealing with Spanish in South America. Jorgelina Illustrator Doug Jones Vacchino, Nicolás Bravo and Eugenia Conti describe how South American Production Sandy Compton translators are trained. Charles Campbell looks at companies that have Editorial Board entered the South American market with different degrees of success. Jeff Allen, Julieta Coirini, Teddy Bengtsson recounts setting up a company in Argentina. And Bill Hall, Aki Ito, Nancy A. Locke, Fabiano Cid explores Brazil, both as an outsourcing option and an Ultan Ó Broin, Angelika -

Continents of the World

Continents of the World A continent is a massive area of land usually separated by water. There are seven continents in the world. Asia Asia is the largest continent in the world. About ⅔ of the people in the world live here. They live in 48 countries, including India, Japan and China. The Himalayas, the tallest mountains in the world, are in Asia. Here you will also find the lowest point on land, the Dead Sea. Asia is home to tigers, monkeys and giant pandas. Page 1 of 5 Continents of the World Africa Africa is the second largest continent in the world. Africa has 54 countries, more than any other continent. These countries include South Africa and Egypt. Africa has the longest river in the world, the Nile. Africa also has the biggest non-polar desert, the Sahara. Africa is home to rhinos, lions, giraffes and elephants. North America North America is the third largest continent. Countries here include the USA, Canada and Mexico. Corn and pumpkins come from North America. Animals found in North America include skunks, bears and moose. South America South America is the fourth largest continent in the world. South America has 12 countries, including Brazil, Peru and Argentina. South America is home to the largest rainforest in the world, the Amazon. The Andes mountain range runs the length of the continent. Potatoes, tomatoes and chocolate come from South America. Animals you will find here include sloths, llamas and jaguars. Page 2 of 5 Continents of the World Antarctica Antarctica is the third smallest continent in the world.