SFA Scholarworks Mother/God

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Artist Release Tracktitle Streaming 2017 1Wayfrank Ayegirl

Report Artist Release Tracktitle Streaming 2017 1wayfrank Ayegirl - Single Ayegirl Streaming 2017 2 Brothers On the 4th Floor Best of 2 Brothers On the 4th Floor Dreams (Radio Version) Streaming 2017 2 Chainz TrapAvelli Tre El Chapo Jr Streaming 2017 2 Unlimited Get Ready for This - Single Get Ready for This (Yar Rap Edit) Streaming 2017 3LAU Fire (Remixes) - Single Fire (Price & Takis Remix) Streaming 2017 4Pro Smiler Til Fjender - Single Smiler Til Fjender Streaming 2017 666 Supa-Dupa-Fly (Remixes) - EP Supa-Dupa-Fly (Radio Version) Lets Lurk (feat. LD, Dimzy, Asap, Monkey & Streaming 2017 67 Liquez) No Hook (feat. LD, Dimzy, Asap, Monkey & Liquez) Streaming 2017 6LACK Loyal - Single Loyal Streaming 2017 8Ball Julekugler - Single Julekugler Streaming 2017 A & MOX2 Behøver ikk Behøver ikk (feat. Milo) Streaming 2017 A & MOX2 DE VED DET DE VED DET Streaming 2017 A Billion Robots This Is Melbourne - Single This Is Melbourne Streaming 2017 A Day to Remember Homesick (Special Edition) If It Means a Lot to You Streaming 2017 A Day to Remember What Separates Me from You All I Want Streaming 2017 A Flock of Seagulls Wishing: The Very Best Of I Ran Streaming 2017 A.CHAL Welcome to GAZI Round Whippin' Streaming 2017 A2M I Got Bitches - Single I Got Bitches Streaming 2017 Abbaz Hvor Meget Din X Ikk Er Mig - Single Hvor Meget Din X Ikk Er Mig Streaming 2017 Abbaz Harakat (feat. Gio) - Single Harakat (feat. Gio) Streaming 2017 ABRA Rose Fruit Streaming 2017 Abstract Im Good (feat. Roze & Drumma Battalion) Im Good (feat. Blac) Streaming 2017 Abstract Something to Write Home About I Do This (feat. -

Eck Gives $20 Million to Disease Center

THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's OLUME 42: ISSUE 116 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 9, 2008 NDSMCOBSERVER.COM Eck gives $20 million to disease center Law- school Gift will benefit CGHID, multi-disciplinary research on global health crisis, biomedical sciences dean to director of the CGHID. Eck's gift will give the "We want to give students By BECKY HOGAN According to its Web site, Center "a number of oppor the opportunity to do News Writer the CGHID brings together tunities we haven't had research and work in dis step do:wn faculty and students from before. While there are a ease-endemic field settings," Notre Dame alumnus several differ.ent colleges and number of faculty who are Collins said. Frank Eck has given the departments at Notre Dame, affiliated with the Center, all Additionally, Collins said O'Hara to leave post University a $20 million gift focusing its research and of their funding is for very the gift will help cover some to support the Center for teaching on human specific research programs," administrative costs, central in 2009 after 10 years Global Health and Infectious pathogens, diseases caused Collins said. "One of the ize all the related research Diseases (CGHID), which will by these organisms and the things we have not had is the currently underway at Notre be renamed the Eck Family impact of these diseases on ability to generate money Dame and enable the Center By PUJA PARIKH Center for Global Health and human society. Members of used for general educational to invite researchers to give News Writer Infectious Diseases. -

Viewers, Some of Whom Were Family from Across the Globe Who Otherwise Would Not Have Been Able to See Their Loved Ones Graduate

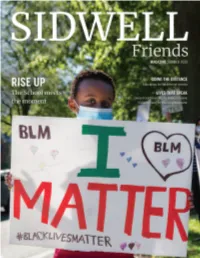

SIDWELL Contents FRIENDS MAGAZINE Summer 2020 Volume 91 Number 3 EDITORIAL DEPARTMENTS Editor-in-Chief Sacha Zimmerman 2 REFLECTIONS FROM THE HEAD OF SCHOOL Art Director 4 ON CAMPUS Meghan Leavitt The School announces the 2020 Newmyer Award Senior Writers honorees; the robotics team tackles 3D-printed masks; Natalie Champ we ask Director of Health Services Jasmin Whitfield five THIS YEAR, Kristen Page questions; local sports maven Chad Ricardo hosts the Alumni Editors School’s Athletic Celebration; and much more. Emma O’Leary 16 THE ARCHIVIST Anna Wyeth 04 EVERYTHING Thomas Sidwell knew how to handle a plague—or three. Contributing Writers Loren Hardenbergh 36 ALUMNI ACTION Caleb Morris New grads ascend to alumni status; Founder’s Day brings CHANGED. Contributing Photographers out alumni for the Let Your Life Speak series. Kelley Lynch Susie Shaffer ’69 40 FRESH INK And when it did, the power of the collective Freed Photography Brett Dakin ’94; Laurence Aurbach ’81; generosity of the Sidwell Friends community Digital Producers Anthony Silard ’85; Ellen Hopman ’70. became even more apparent. Anthony La Fleur 43 CLASS NOTES Sarah Randall Annual Fund donors provided teachers with the ability Spoiler alert: Everyone is sheltering in place. LEADERSHIP to quickly adapt and connect with students over new 18 83 WORDS WITH FRIENDS technologies. You ensured that every student had the Head of School “A Social-Distancing Puzzle” resources to continue learning on new digital platforms. Bryan K. Garman Chief Communications Officer 84 LAST LOOK You enabled the School to quickly respond to families Hellen Hom-Diamond “Lose Yourself” who faced unprecedented financial hardship. -

Proof of Heaven

This book is dedicated to all of my loving family, with boundless gratitude. CONTENTS Prologue 1. The Pain 2. The Hospital 3. Out of Nowhere 4. Eben IV 5. Underworld 6. An Anchor to Life 7. The Spinning Melody and the Gateway 8. Israel 9. The Core 10. What Counts 11. An End to the Downward Spiral 12. The Core 13. Wednesday 14. A Special Kind of NDE 15. The Gift of Forgetting 16. The Well 17. N of 1 18. To Forget, and to Remember 19. Nowhere to Hide 20. The Closing 21. The Rainbow 22. Six Faces 23. Final Night, First Morning 24. The Return 25. Not There Yet 26. Spreading the News 27. Homecoming 28. The Ultra-Real 29. A Common Experience 30. Back from the Dead 31. Three Camps 32. A Visit to Church 33. The Enigma of Consciousness 34. A Final Dilemma 35. The Photograph Eternea Acknowledgments Appendix A: Statement by Scott Wade, M.D. Appendix B: Neuroscientific Hypotheses I Considered to Explain My Experience Reading List Index PROLOGUE A man should look for what is, and not for what he thinks should be. —ALBERT EINSTEIN (1879–1955) When I was a kid, I would often dream of flying. Most of the time I’d be standing out in my yard at night, looking up at the stars, when out of the blue I’d start floating upward. The first few inches happened automatically. But soon I’d notice that the higher I got, the more my progress depended on me—on what I did. -

Discovering the Student Discovering the Self

Discovering the Student Discovering the Self Essays from ENG 100 Students 2016-17 English and Modern Languages Department Missouri Western State University Introduction Dawn Terrick The essays that appear in this publication were selected by the English 100 Committee from submissions from English 100 students from the Spring and Fall 2016 semesters. The criteria used to evaluate and select these essays included content, originality, a sense of discovery and insight on the part of the student writer, control of form, language and sentence construction and representation of the various types of assignments students are engaged in while in this course. ENG 100, Introduction to College Writing, is a developmental composition course designed for students who show signs of needing additional work on their college-level writing before starting the regular general education composition classes. In this course, students learn about and refine their writing process with a strong focus on the act of revision, engage in critical reading, thinking and writing and write both personal and text-based essays. ENG 100 prepares students for the rigors of college-level writing and introduces them to college expectations. It is our hope that these student essays reflect the struggle and the joy, the hard work and the rewards that these students have experienced both in their lives and in the classroom. Furthermore, these essays reflect the diversity of our English 100 students and the uniqueness of this course. Our students are entering college straight out of high school and are returning to the classroom after years of work and family, come from urban and rural areas, and represent different races and cultures. -

For Logan. I've Only Just Met You and Already I Love You

For Logan. I’ve only just met you and already I love you. She was glad that the cosy house, and Pa and Ma and the fire-light and the music, were now. They could not be forgotten, she thought, because now is now. It can never be a long time ago. —LAURA INGALLS WILDER, Little House in the Big Woods Time is the longest distance between two places. —TENNESSEE WILLIAMS, The Glass Menagerie Dear Peter, I miss you. It’s only been five days but I miss you like it’s been five years. Maybe because I don’t know if this is just it, if you and I will ever talk again. I mean I’m sure we’ll say hi in chem class, or in the hallways, but will it ever be like it was? That’s what makes me sad. I felt like I could say anything to you. I think you felt the same way. I hope you did. So I’m just going to say anything to you right now, while I’m still feeling brave. What happened between us in the hot tub scared me. I know it was just a day in the life of Peter for you, but for me it meant a lot more, and that’s what scared me. Not just what people were saying about it, and me, but that it happened at all. How easy it was, how much I liked it. I got scared and I took it out on you and for that I’m truly sorry. -

Always Sometimes Monsters 03

Chris Lewis Carter I’M ABOUT TO close shop when a kid walks in, no older than eight or nine, lugging a cardboard box with Do Not Open Ever scrawled on the side. He pushes it onto the counter and stares at me with expectation. “Do you buy video games?” I gesture to the hundreds of plastic cases lining the shelves. “Let’s see, this is a used game store. What do you think?” “Okay,” he says, clearly not catching the sarcasm. “These are for sale.” I pry open the flaps, unleashing a stench like the inside of a damp basement. “Ugh, fantastic.” I fan the air until it’s semi-breathable. “Where did you find this stuff?” “My mom found it,” he says, rocking back and forth on his heels. “Inside our new house.” I remove a stack of software from the box. “You live in a sewer or something?” “No. Baker Street.” He picks up a strategy guide, flips through a few pages, then puts it back on the rack. “I’m not allowed to play video games. Mom says they’re a bad influence.” games. Mom says they’re a bad influence.” Those words never fail to get me started. “Well, your mom needs to join the twenty-first century. Games are entertainment, not serial- killer training manuals. Besides, they’re no more violent than a typical news broadcast. Statistically speaking--” But the kid isn’t listening anymore. He’s busy watching the demo kiosk replay my last lap of Rocket Racers. So much for educating the next generation. -

Cantos a Literary and Arts Journal Missouri Baptist University 2 017 Cantos a Literary and Arts Journal

Cantos A Literary and Arts Journal Missouri Baptist University 2 017 Cantos A Literary and Arts Journal EDITOR John J. Han ASSISTANT EDITORS Krista Krekeler Krista Tyson EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Mary Ellen Fuquay Douglas T. Morris EDITORIAL INTERN Lucas Bennett (Abilene Christian University, TX) EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS Ben Moeller-Gaa C. Clark Triplett COVER ART COVER DESIGN Carol Sue Horstman Jenny Sinamon Cantos: A Literary and Arts Journal is published every summer by the Department of English at Missouri Baptist University. Its goal is to provide creative writers and artists with a venue for self-expression and to cultivate aesthetic sensibility among scholars and students. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Missouri Baptist University. Compensation for contributions is one copy of Cantos, and copyrights revert to authors and artists upon publication. SUBMISSIONS: Cantos welcomes submissions from the students, faculty, staff, alumni, and friends of Missouri Baptist University. Send previously unpublished poems, short fiction, excerpts from a novel in progress, and nonfiction as e-mail attachments (Microsoft Word format) to the editor, John J. Han, at [email protected] by March 15. Send previously unpublished artwork, including haiga (illustrated haiku), as an e-mail attachment to the editor, John J. Han, at [email protected] by the same date. For more details, read the submission guidelines on the last page of this issue. SUBSCRIPTIONS & BOOKS FOR REVIEW: Cantos subscriptions, renewals, address changes, and books for review should be mailed to John J. Han, Editor of Cantos, Missouri Baptist University, One College Park Drive, St. -

The Borgia Apocalypse

THE BORGIA APOCALYPSE Written by NEIL JORDAN InkWell Publishing Published in eBook format by InkWell Publishing 521 5th Avenue, 26th Floor New York, NY 10175 Original Copyright 2013 by Neil Jordan eBook Copyright 2013 by Neil Jordan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without the prior written consent of the Publisher, excepting brief quotes used in reviews. INTRODUCTION I first wrote about the Borgias as an historical film. It was the second historical subject I had attempted – the first was Michael Collins, the film I made for Warner Brothers about the Irish guerrilla leader and the Irish War of Independence. On Michael Collins, I experienced the dilemma of the historical screenplay – the mass of material that has to be encapsulated within a two-hour time frame. So when Dreamworks suggested that I develop a Borgia project as a cable series for Showtime, I saw it as a unique opportunity to write a 40-hour film, about power, religion and sex in the Renaissance period. It would be as lurid and dramatic as any Jacobean drama, but over four seasons, long enough to do justice to the complexity of the times and the family. Halfway through the shooting of the third season, I received word that the new regime at Showtime might not want to continue with the fourth. The series was expensive to produce, since we always did our utmost to do justice to the architecture, design and costume of the period, however free we allowed ourselves to be with the actual events. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Pirate Child Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/306350wv Author Harris, Danielle Marie Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Pirate Child A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performance Arts by Danielle Marie Harris June 2011 Thesis Committee: David Ulin, Co-Chairperson Stuart Krieger, Co-Chairperson Deanne Stillman Copyright by Danielle Marie Harris 2011 The Thesis of Danielle Marie Harris is approved: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson __________________________________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside 1. “Think this’ll be it?” I asked. From the passenger side window, the world was a blur. Not because my mom and I were speeding down the 405 freeway at 80. No, we were at a dead standstill between the catering van in front of us and an expensive sports car behind, enjoying LA rush hour at seven in the morning. For miles, I could see the shimmering outlines of what I assumed to be cars stacked upon cars. Because of my patch, the scenery—cinderblock walls with trees peeking their heads above—appeared to be whizzing by in grey and green smudges, none of it holding its shape, all blurring like it would to normal eyes when seen from a moving car window. And I was beginning to get frustrated with the not-funny joke of really being stuck in one place. -

Alumni Journal

Bashe et al.: Alumni Journal GEARING UP FOR FALL THIS FALL, SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY WILL WELCOME THE SECOND largest group of first-year students in its history. The Class of 2013 is our best group yet, except for that outstand ing group that I came to campus with in 1962! Traditions » Never has a class been better prepared for be ginning its higher education career. SU alumni Raised on the Radio: clubs all over the country stage send-offs for new students and their parents. The ReadySet WJPZ Draws Power publication, produced by the Office of First from Alumni Involvement Year and Transfer Programs, provides useful guidance to incoming students. Put another FROM DICK CLARK '51 , WHO BEGAN SPINNING RE way, these students are much better prepared cords as an SU student, to Alex Silverman '10, who will than we were. spend his senior year as a professional news broad Would you like to meet some of these stu caster, Syracuse University has earned a reputation in dents? Well, join us on campus from October American radio as a breeding ground for performers, 1-4 at Orange Central, an exciting blend of journalists, executives, and industry operatives of every Homecoming+Reunion. This will be our third type. The rigors of a Newhouse education, according year of combining the two events. The most common reaction from to many alumni, do not fully explain this phenomenal those who have attended the combined event is the excitement of cel success story. For that, it is necessary to include the ebrating reunion when students are on campus. -

10 Years Battle Lust Now Is the Time (Ravenous)

10 Years Ace Frehley Battle Lust Outer Space Now Is The Time (Ravenous) Shoot It Out The Acro-brats Day Late, Dollar Short 3 Doors Down Here Without You Aerosmith It's Not My Time Back in the Saddle Kryptonite Cryin' When I'm Gone Dream On When You're Young Dream On (Live) I Don't Want to Miss a Thing 30 Seconds to Mars Legendary Child Attack Love In An Elevator Closer to the Edge Lover Alot From Yesterday Sweet Emotion Kings and Queens Train Kept A Rollin' The Kill Uncle Salty This Is War Walk This Way Woman of the World 311 Amber AFI Beautiful Disaster Beautiful Thieves Down Dancing Through Sunday End Transmission 38 Special Girl's Not Grey Caught Up In You Love Like Winter Hold On Loosely Medicate Miss Murder 4 Non Blondes The Leaving Song, Pt. II What's Up The Missing Frame a-ha After the Burial Take on Me Aspiration Berzerker ABBA Cursing Akhenaten Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midni... My Frailty Pendulum Abnormality Your Troubles Will Cease and Fortune Wi... Visions Against Me! AC/DC New Wave Back in Black (Live) Stop! Big Gun Thrash Unreal Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) Fire Your Guns (Live) Airbourne For Those About to Rock (We Salute You)... Runnin' Wild Heatseeker (Live) Too Much, Too Young, Too Fast Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) Hells Bells (Live) Alanis Morissette High Voltage (Live) Head Over Feet Highway to Hell (Live) Ironic Jailbreak (Live) You Oughta Know Let Me Put My Love Into You Let There Be Rock (Live) Alice Cooper Moneytalks (Live) Billion Dollar Babies (Live) Shoot to Thrill (Live) Elected T.N.T.