''Can You Handle My Truth?'': Authenticity and the Celebrity Star

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463 June 1, 2021 CERTIFIED MAIL – RETURN RECEIPT REQUESTED Via Email: Pryan@Commo

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463 June 1, 2021 CERTIFIED MAIL – RETURN RECEIPT REQUESTED Via Email: [email protected] Paul S. Ryan Common Cause 805 15th Street, NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20005 RE: MUR 7324 Dear Mr. Ryan: The Federal Election Commission (“Commission”) has considered the allegations contained in your complaint dated February 20, 2018. The Commission found reason to believe that respondents David J. Pecker and American Media, Inc. knowingly and willfully violated 52 U.S.C. § 30118(a). The Factual and Legal Analysis, which formed a basis for the Commission’s finding, is enclosed for your information. On May 17, 2021, a conciliation agreement signed by A360 Media, LLC, as successor in interest to American Media, Inc. was accepted by the Commission and the Commission closed the file as to Pecker and American Media, Inc. A copy of the conciliation agreement is enclosed for your information. There were an insufficient number of votes to find reason to believe that the remaining respondents violated the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended (the “Act”). Accordingly, on May 20, 2021, the Commission closed the file in MUR 7324. A Statement of Reasons providing a basis for the Commission’s decision will follow. Documents related to the case will be placed on the public record within 30 days. See Disclosure of Certain Documents in Enforcement and Other Matters, 81 Fed. Reg. 50,702 (Aug. 2, 2016), effective September 1, 2016. MUR 7324 Letter to Paul S. Ryan Page 2 The Act allows a complainant to seek judicial review of the Commission’s dismissal of this action. -

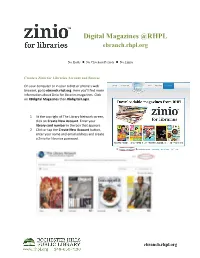

Digital Magazines @RHPL Ebranch.Rhpl.Org

Digital Magazines @RHPL ebranch.rhpl.org No Holds No Checkout Periods No Limits Create a Zinio for Libraries Account and Browse On your computer or in your tablet or phone’s web browser, go to ebranch.rhpl.org. Here you’ll find more information about Zinio for libraries magazines. Click on RBdigital Magazines then Rbdigital Login. 1. At the top right of The Library Network screen, click on Create New Account. Enter your library card number in the box that appears. 2. Click or tap the Create New Account button, enter your name and email address and create a Zinio for libraries password. ebranch.rhpl.org You are now logged into the RHPL Zinio for Libraries digital magazine site and can read all of the magazines you see in the site. Once you find a magazine you’d like to read: 1. Click or tap on the add button and then click or tap Start Reading to read the magazine right away 2. OR click or tap on the cover to read a description of the magazine or view back issues and select an older issue to read. A new tab will open on your internet browser and you can read the magazine in this tab on your PC or Mac. (Please note: to read magazines on your tablet you will need to download a separate Zinio for Libraries app) Read Your Magazines Note: You must first browse for and download magazines using a web browser on your computer or mobile device. Computer users - Zinio for Libraries is available for use entirely in your internet web browser. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Fame Attack : the Inflation of Celebrity and Its Consequences

Rojek, Chris. "The Icarus Complex." Fame Attack: The Inflation of Celebrity and Its Consequences. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 142–160. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849661386.ch-009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 16:03 UTC. Copyright © Chris Rojek 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 9 The Icarus Complex he myth of Icarus is the most powerful Ancient Greek parable of hubris. In a bid to escape exile in Crete, Icarus uses wings made from wax and feathers made by his father, the Athenian master craftsman Daedalus. But the sin of hubris causes him to pay no heed to his father’s warnings. He fl ies too close to the sun, so burning his wings, and falls into the Tsea and drowns. The parable is often used to highlight the perils of pride and the reckless, impulsive behaviour that it fosters. The frontier nature of celebrity culture perpetuates and enlarges narcissistic characteristics in stars and stargazers. Impulsive behaviour and recklessness are commonplace. They fi gure prominently in the entertainment pages and gossip columns of newspapers and magazines, prompting commentators to conjecture about the contagious effects of celebrity culture upon personal health and the social fabric. Do celebrities sometimes get too big for their boots and get involved in social and political issues that are beyond their competence? Can one posit an Icarus complex in some types of celebrity behaviour? This chapter addresses these questions by examining celanthropy and its discontents (notably Madonna’s controversial adoption of two Malawi children); celebrity health advice (Tom Cruise and Scientology); and celebrity pranks (the Sachsgate phone calls involving Russell Brand and Jonathan Ross). -

This Is “Magazines”, Chapter 5 from the Book Culture and Media (Index.Html) (V

This is “Magazines”, chapter 5 from the book Culture and Media (index.html) (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This content was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. i Chapter 5 Magazines Changing Times, Changing Tastes On October 5, 2009, publisher Condé Nast announced that the November 2009 issue of respected food Figure 5.1 magazine Gourmet would be its last. The decision came as a shock to many readers who, since 1941, had believed that “Gourmet was to food what Vogue is to fashion, a magazine with a rich history and a perch high in the publishing firmament.”Stephanie Clifford, “Condé Nast Closes Gourmet and 3 Other Magazines,” New York Times, October 6, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/ 10/06/business/media/06gourmet.html. -

Radio 2 Paradeplaat Last Change Artiest: Titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley

Radio 2 Paradeplaat last change artiest: titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley Moody Blue 10 2 David Dundas Jeans On 15 3 Chicago Wishing You Were Here 13 4 Julie Covington Don't Cry For Me Argentina 1 5 Abba Knowing Me Knowing You 2 6 Gerard Lenorman Voici Les Cles 51 7 Mary MacGregor Torn Between Two Lovers 11 8 Rockaway Boulevard Boogie Man 10 9 Gary Glitter It Takes All Night Long 19 10 Paul Nicholas If You Were The Only Girl In The World 51 11 Racing Cars They Shoot Horses Don't they 21 12 Mr. Big Romeo 24 13 Dream Express A Million In 1,2,3, 51 14 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 19 15 Champagne Oh Me Oh My Goodbye 2 16 10CC Good Morning Judge 12 17 Glen Campbell Southern Nights 15 18 Andrew Gold Lonely Boy 28 43 Carly Simon Nobody Does It Better 51 44 Patsy Gallant From New York to L.A. 15 45 Frankie Miller Be Good To Yourself 51 46 Mistral Jamie 7 47 Steve Miller Band Swingtown 51 48 Sheila & Black Devotion Singin' In the Rain 4 49 Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers Egyptian Reggae 2 1978 11 Chaplin Band Let's Have A Party 19 1979 47 Paul McCartney Wonderful Christmas time 16 1984 24 Fox the Fox Precious little diamond 11 52 Stevie Wonder Don't drive drunk 20 1993 24 Stef Bos & Johannes Kerkorrel Awuwa 51 25 Michael Jackson Will you be there 3 26 The Jungle Book Groove The Jungle Book Groove 51 27 Juan Luis Guerra Frio, frio 51 28 Bis Angeline 51 31 Gloria Estefan Mi tierra 27 32 Mariah Carey Dreamlover 9 33 Willeke Alberti Het wijnfeest 24 34 Gordon t Is zo weer voorbij 15 35 Oleta Adams Window of hope 13 36 BZN Desanya 15 37 Aretha Franklin Like -

Sunday Times Magazine 11.11.2012 the Sunday Times Magazine 11.11.2012 17 VIVA FOREVER!

VIVA FOREVER! WESTSPICE UP YOUR LIFE END Brainchild of the Mamma Mia! producer Judy Craymer and written by Jennifer Saunders, the Spice Girls musical Viva Forever! launches next month. Giles Hattersley goes backstage to discover if it’s what the band want, what they really really want VIVA FOREVER! n a rehearsal room in south London, two me just before the film of Mamma Mia! came young actors are working on a scene with out [in 2008]. I sent Simon an email, saying WHERE ARE THEY NOW? all the earnest dedication required of I had to concentrate on the movie. Obviously, Baby, 36 Emma Bunton had a Ibsen. This is not Ibsen, however. At the you don’t write letters like that to Simon,” she successful solo career before back of the room, massive signs are laughs, “because I didn’t hear from him again. moving into radio presenting propped against the wall, spelling out the But I did hear from Geri in 2009. She wrote a (she has a show on Heart). immortal girl-band mantra: “Who do you sweet email, so I met her and Emma [Bunton].” She’s also been a recurring character on think you are?” It’s an existential puzzler In fact, the girls had wanted to do a musical Absolutely Fabulous and has two sons Ithat performers are encouraged to struggle for years. “It was an idea that was talked about with Jade Jones of the boyband Damage with as they wrestle with other deep emotional all the time,” says Halliwell, but Craymer fare, such as, “I’ll tell you what I want, what I hadn’t been looking to do another jukebox Ginger, 40 After quitting the Y really, really want.” Today, the show’s two leads musical (a term she hates). -

'Perfect Fit': Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity

‘Perfect Fit’: Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity Culture in Fashion Television Helen Warner Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies Submitted July 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. Helen Warner P a g e | 2 ABSTRACT According to the head of the American Costume Designers‟ Guild, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, fashion is emphatically „not costume‟. However, if this is the case, how do we approach costume in a television show like Sex and the City (1998-2004), which we know (via press articles and various other extra-textual materials) to be comprised of designer clothes? Once onscreen, are the clothes in Sex and the City to be interpreted as „costume‟, rather than „fashion‟? To be sure, it is important to tease out precise definitions of key terms, but to position fashion as the antithesis of costume is reductive. Landis‟ claim is based on the assumption that the purpose of costume is to tell a story. She thereby neglects to acknowledge that the audience may read certain costumes as fashion - which exists in a framework of discourses that can be located beyond the text. This is particularly relevant with regard to contemporary US television which, according to press reports, has witnessed an emergence of „fashion programming‟ - fictional programming with a narrative focus on fashion. -

Flipster Magazines

Flipster Magazines Cricket AARP the Magazine Crochet! Advocate (the) Cruising World AllRecipes Current Biography Allure Curve Alternative Medicine Delight Gluten Free Amateur Gardening Diabetic Self-Management Animal Tales Discover Architectural Digest DIVERSEability Art in America Do It Yourself Artist's Magazine (the) Dogster Ask Dr. Oz: The Good Life Ask Teachers Guide Dwell Astronomy Eating Well Atlantic (the) Entertainment Weekly Audiofile Equus Audobon Faces BabyBug Faces Teachers Guide Baseball Digest FIDO Friendly Bazoof Fine Cooking BBC Easy Cook Fine Gardening BBC Good Food Magazine First for Women Beadwork Food Network Magazine Birds and Blooms Food + Wine Bloomberg Businessweek Foreward Reviews Bon Appetit Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide Book Links Girlfriend Booklist Golf Magazine BuddhaDharma Good Housekeeping Catster GQ Chess Life Harvard Health Letter Chess Life for Kids Harvard Women's Health Watch Chickadee Health Chirp High Five Bilingue Christianity Today Highlights Cinema Scope Highlights High Five Clean Eating History Magazine Click Horn Book Magazine COINage In Touch Weekly Commonweal Information Today Computers in Libraries Inked Craft Beer and Brewing InStyle J-14 LadyBug Sailing World LadyBug Teachers Guide School Library Journal Library Journal Simply Gluten Free Lion's Roar Soccer 360 Martha Stewart Living Spider Men's Journal Spider Teachers Guide Mindful Spirituality & Health Modern Cat Sports Illustrated Modern Dog Sports Illustrated Kids Muse Taste of Home Muse Teachers Guide Teen Graffiti Magazine National -

2011 Kevin & Bean Clips Listed by Date

2011 Kevin & Bean clips listed by date January 03 Monday 01 Opening Segment-2011-01-03-No What It Do Nephew segment.mp3 02 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-6 am.mp3 03 Highlights Of Dick Clark and Ryan Seacrest-New Years Eve-2011-01-03.mp3 04 Harvey Levin-TMZ-2011-01-03.mp3 05 The Internet Round-up-2011-01-03.mp3 06 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-7 am.mp3 07 Thanks For That Info Bean-2011-01-03.mp3 08 Broken New Years Resolutions-2011-01-03.mp3 09 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-8 am.mp3 10 Eli Manning-2011-01-03-Turns 30 Today.mp3 11 Patton Oswalt-2011-01-03-New Book Out.mp3 12 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-9 am-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 13 Dick Clark New Years Eve-More Highlights-2011-01-03-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 14 Calling Arkansas About 2000 Dead Birds-2011-01-03-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 15 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-10 am.mp3 January 04 Tuesday 01 Opening Segment-2011-01-04.mp3 02a Bean Did Not Realize It Was King Of Mexicos Birthday-2011-01-04.mp3 02b Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-6 am.mp3 03 Calling Arkansas About 2000 Dead Birds-from Monday 2011-01-03-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 04 and 14 Hotline To Heaven-2011-01-04-Michael Jackson.mp3 05 Oprah Rules In Kevins House-2011-01-04.mp3 06 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-7 am.mp3 07 Strange Addictions-2011-01-04-Listener Call-in.mp3 08 Paula Abdul-2011-01-04-On Her New TV Show.mp3 09 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-8 am.mp3 10 Bean Passed Out On Christmas Eve-2011-01-04-Wife Donna Explains.mp3 11 Psycho Body-2011-01-04.mp3 12 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-9 am.mp3 13 Afro Calls-2011-01-04.mp3 15 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-10 am.mp3 -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

Electronically FILED by Superior Court of California, County of Los Angeles 8/30/2021 3:16 PM Sherri R. Carter, Executive Officer/Clerk, By Arianna Smith, Deputy Clerk 1 GREENBERG TRAURIG, LLP MATHEW S. ROSENGART (SBN 255750) ([email protected]) 2 ERIC V. ROWEN (SBN 106234) ([email protected]) SCOTT D. BERTZYK (SBN 116449) ([email protected]) 3 LISA C. MCCURDY (SBN 228755) ([email protected]) MATTHEW R. GERSHMAN (SBN 253031) ([email protected]) 4 JANE H. DAVIDSON (SBN 326547) ([email protected]) 1840 Century Park East, Suite 1900 5 Los Angeles, CA 90067-2121 Tel: 310-586-3889 6 Fax: 310-586-7800 7 Attorneys for Conservatee Britney Jean Spears 8 9 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 10 COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES, CENTRAL DISTRICT 11 12 In re the Conservatorship of the Person and Case No. BP108870 Estate of 13 Hon. Brenda J. Penny, Dept. 4 BRITNEY JEAN SPEARS, 14 CONSERVATEE BRITNEY SPEARS’S Conservatee. SUPPLEMENTAL PETITION FOR 15 SUSPENSION AND REMOVAL OF JAMES P. SPEARS AS CONSERVATOR OF THE ESTATE 16 PURSUANT TO PROBATE CODE SECTION 2650(j) 17 Date: September 29, 2021 18 Time: 1:30 PM Dept: 4 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 1 SUPPLEMENTAL PETITION FOR SUSPENSION AND REMOVAL 1 SUPPLEMENTAL PETITION 2 I. INTRODUCTION 3 1. Britney Spears established in her July 26, 2021 Verified Petition for Suspension and 4 Removal of James P. Spears (the “Petition”) that Mr. Spears’s suspension and removal were mandated 5 under Probate Code Section 2650(j) because, as a matter of law, this relief is “in the best interests of” Ms. -

Jeffrey Sachs Reith Lectures 2007: Bursting at the Seams

Jeffrey Sachs Reith Lectures 2007: Bursting at the Seams Lecture 1: Bursting at the Seams Recorded at the Royal Society, London SUE LAWLEY: Hello and welcome to the Royal Society in London, a place where, since its foundation in 1660, great minds have gathered to discuss the important scientific issues of the day. It's a fitting place to introduce this year's Reith lecturer, a man who believes we need a new enlightenment to solve many of the world's problems. The American press has hailed him as one of the world's most influential people, a plaudit due in some measure no doubt to the fact that he's not afraid to put his theories to the test. Like one of his great heroes, John Maynard Keynes, he's moved between the academic life and politics, working successfully with governments in South America and Eastern Europe to help restore their broken economies. In this series of Reith Lectures he'll be explaining how he believes that with global co-operation our resources can be harnessed to create a more equal and harmonious world. If we cannot achieve this, he says, we will face catastrophe; we'll simply be overwhelmed by disease, hunger, pollution, and the clash of civilisations. In this, the first of his series of five lectures, he begins by setting the scene, describing an over-populated world on the brink of devastating change, a world that, as the title of the lecture says, is bursting at the seams. Ladies and gentlemen will you please welcome the BBC's Reith Lecturer 2007 - Jeffrey Sachs.