The Yorkshire Journal Issue 1 Spring 2015 Above: Oakwell Hall, West Yorkshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ben Rhydding Cross Country Reception Girls

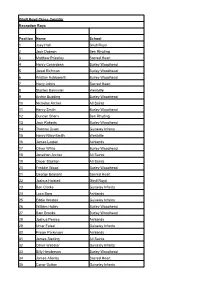

Ben Rhydding Reception Girls Saturday 24th November Cross Country Position Name School 1 Briony Healy Sacred Heart 2 Mia Beck Sacred Heart 3 Lily Robson Ben Rhydding 4 Lilaby Morse Moorfield 5 Ellie Starr Ben Rhydding 6 Ellie Ramsbotttom Burley Woodhead 7 Jessica Wells Addingham 8 Ellie Hopwood Burley Woodhead 9 Sophie White Ashlands 10 Anna Barker Ashlands 11 Charlie Murray Addingham 12 Ellie Mawson All Saints 13 Pippa Hunter Rae Addingham 14 Ella Hyde Burley Woodhead 15 Sophie Leonard Sacred Heart 16 Annabel Cole Addingham 17 Natalie Redding Burley Woodhead 18 Caitlin Oddie Ashlands 19 Ciara Kleppel Sacred Heart 20 Maere Barrett Burley Woodhead Ben Rhydding Reception Girls Saturday 24th November Cross Country Position School Points 1 Sacred Heart 37 2 Burley Woodhead 45 3 Addingham 47 Ben Rhydding Reception Boys Saturday 24th November Cross Country Position Name School 1 James Patchett 2 Edward Riley Ashlands 3 Jack Fendyke Burley Woodhead 4 Miles Rochford Sacred Heart 5 Jamie Woolston Burley Woodhead 6 Tommy Hagan Burley Woodhead 7 Alfie Weston Ghyll Royd 8 Jospeph Williams Sacred Heart 9 Jamie Sykes All Saints 10 Tom Jackson Burley Woodhead 11 Joseph Linneker Burley Woodhead 12 Theo Labbett Sacred Heart 13 Joseph Rutter Addingham 14 Oliver Scott-Caro Addingham 15 Harvey Stapleton Addingham 16 Harrison Beel Burley Woodhead 17 Oliver Gray 18 James Newman Burley Woodhead 19 Zak Rogers Ashlands 20 Joe Reynier Sacred Heart 21 Luke Pearse Ashlands 22 Thomas Broadbent Addingham Ben Rhydding Reception Boys Saturday 24th November Cross Country -

Meadow Croft Farm Birch Close Lane High Eldwick Bingley Bd16 3Bg

MEADOW CROFT FARM BIRCH CLOSE LANE HIGH ELDWICK BINGLEY BD16 3BG A DELIGHTFUL FOUR BEDROOMED BARN CONVERSION FULL OF CHARM AND CHARACTER, WITH GENEROUS GARDENS AND SUPERB FAR REACHING VIEWS OVER THE VALLEY A rare opportunity to acquire a delightful rural property located in an idyllic setting with far reaching views over the valley. Meadow Croft Farm has been sympathetically converted creating a characterful and charming family home retaining many original features. The beautifully presented accommodation comprises a sitting room, dining kitchen and cloakroom, whilst to the first floor there is a master bedroom with mezzanine storage and dressing areas, three further bedrooms and bathroom. Outside the property is set in well maintained and generous gardens with a double garage and ample off road parking. PRICE: £475,000 15 The Grove, Ilkley, West Yorkshire, LS29 9LW Telephone: 01943 817642 Facsimile: 01943 816892 www.daleeddison.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] Birch Close Lane ( continued ) This charming property enjoys a lovely rural setting only a short distance from Eldwick village, which is a popular and thriving community situated within easy reach of neighbouring Bingley, Baildon and Guiseley. There is a range of local shops and schools available in the area together with a variety of sporting and recreational facilities whilst open countryside and pleasant walks including nearby Baildon Moor and Shipley Glen are close at hand. In addition, a commuter rail service to Leeds/Bradford city centres is available from Bingley station with further stations in nearby Guiseley and Baildon. The charming accommodation with LPG CENTRAL HEATING, SEALED UNIT DOUBLE GLAZING, PINE PANELLED INTERIOR DOORS, STONE WINDOW SILLS, EXPOSED BEAMS and with approximate room sizes comprises: GROUND FLOOR SITTING ROOM 22' x 17' 8" (6.71m x 5.38m) BATHROOM A stunning reception room with an impressive brick fireplace An impressive bathroom with a high ceiling and velux window. -

Service Changes

Service changes The latest info Including on all that’s • Route changes happening with • Timetable changes your buses in & around • New services Bradford from Sunday 25 October 2015 Need more info? online firstgroup.com/bradford 0700-1900 Mon-Fri call us 0113 381 5000 0900-1700 Sat tweet @FirstWestYorks Service Changes from 25 October 2015 What’s changing? We continually review the use of our commercial network and are making some changes to ensure we use our resources to best meet customer demand. We’ve also taken the opportunity to make some changes to some of our longest routes, so that customers on one side of the city aren’t affected as much by delays, disruption and traffic on the opposite side of the city. Broadway Shopping Centre This great new facility in the centre of Bradford opens on Thursday 5 November - and with all of our services stopping close by, using the bus is an ideal way to get there! Bradford Area Tickets - extended to Pudsey! We’ve received a number of requests from customers, following the improvements to service 611 in August, so we’re revising the boundary of our Bradford day, week, month and year tickets to include the full 611 route between Bradford and Pudsey. On Hyperlink 72, these Bradford area tickets will be valid as far as Thornbury Barracks. Service changes Service 576 minor route change Halifax – Queensbury – Bradford In Bradford the route of this service will change, with buses running via Great Horton Road, serving the University of Bradford and Bradford College, replacing services 613/614. -

Bradford & District Rabbits Golf Association Www

BRADFORD & DISTRICT RABBITS GOLF ASSOCIATION WWW.BDRGA.NET B.D.R.G.A. HANDBOOK 2019 BRADFORD & DISTRICT RABBITS GOLF ASSOCIATION The following is an extract from the MINUTES of the inaugural Meeting of the new ASSOCIATION, which was referred to as THE BRADFORD & DISTRICT RABBITS GOLF ASSOCIATION dated 9th April 1948. “Invitations to attend this Meeting had been sent out by a small Committee of the Bradford Moor Golf Club, and the response was very encouraging. There was an attendance of 28 and eleven Clubs were represented as follows:- South Bradford, Bradford Moor, Otley, Cleckheaton, West Bowling, Woodhall Hills, Queensbury, Thornton, East Bierley, West Bradford and Phoenix Park. The Chair was taken by Sam Chippendale Esq. of Bradford Moor Golf Club and he extended a hearty welcome to all the visitors”. There followed a discussion: “Mr Chippendale was asked whether the Association would have the support of the West Riding Rabbits Golf Association as it was felt that such support and approval would be necessary if both Associations were to prosper. The Chairman said that he had the goodwill of the West Riding Rabbits but assured those present that our Association would be a separate entity from that body and would only be affiliated to it. Thereupon a proposal was made by the Cleckheaton Representative, and seconded by the South Bradford Representative that “The Bradford & District Rabbits Golf Association” be, and is hereby formed, and this was carried without opposition. It was agreed by Members of the Association that an ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING of the Association would be held at a suitable venue on April 30th 1948.” THE BRADFORD & DISTRICT RABBITS GOLF ASSOCIATION CONSTITUTION AND RULES The name of the Association shall be “The Bradford & District Rabbits Golf Association“, affiliated to the Yorkshire Rabbit Golf Association. -

Christian Science Church, Wells Road, Ilkley

The Hermit Inn Burley Woodhead DESIGN AND ACCESS STATEMENT HERITAGE STATEMENT The Hermit has a long history with the earliest parts of the building dating from the mid 18th Century. The public house was formerly known as the Woolpack but the name changed to The Hermit in honour of Job Senior, a local eccentric who lived in a hut on the moor. Local folklore recalls that Senior serenaded crowds of locals who congregated at his “primitive domicile” by Coldstone Beck, above Robin Hole. According to Burley Local History South elevation Group, Senior was born in 1780 and w ith West / North elevations (below) worked as a labourer before retiring to his shack on Ilkley Moor. After which, he received donations from those who came to hear his chants. Senior’s funeral drew a huge number of mourners and he is buried in the churchyard in Burley-in-Wharfedale. The black and white photograph (left) of a hunt meeting probably dates from the 1930’s (or slightly earlier) following the John Smith’s purchase of the pub in 1920. The building is recorded in their archives as the ‘Hermit Inn and Brewhouse’. North elevation circa 1930 1847 OS 1889 OS Peter Harrison Architects January 2021 The accompanying Planning Statement discusses the reasons why a change of use to residential occupation provides the most appropraite means of ensuring the survival of this building in a form that respects it’s long history as a public house. During the second half of the twentieth century a series of licencees undertook a number of alterations to the original building in attempts to diversify the business in the face of falling income from the core business. -

The Edinburgh Gazette, October 1, 1912

1006 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, OCTOBER 1, 1912. BANKRUPTS. William Newens Ward, 13 Conway Road, Luton, in the county of Bedford, lately carrying on business at FROM THE LONDON GAZETTE. 41 Adelaide Street, Luton aforesaid, straw hat manufacturer. John Joseph Henderson, residing at 5 Windsor Road, RECEIVING OBDEBS. Linthorpe, Middlesbrough, in the county of York, Edwin John Barratt, 11 George Street, Hanover Square, and carrying on business at 3 Commercial Buildings, in the county of London, lately residing at The Wilson Street, Middlesbrough aforesaid, coal merchant. Cottage, Southview Drive, Westcliff-on-Sea, and now William Sayer, Bradfield, Norfolk, wheelwright and residing at 12 Woodfield Road, Leigh-on-Sea, both in coachbuilder. Essex, tailor (trading in copartnership with the firm Ada Sheppard, residing and trading at 22 Arkwright of Broom, Barratt, & Howell). Street, Nottingham, dressmaker (spinster). Mrs. Caton, 9 Lancaster Gate Terrace, Hyde Park, in George Humphries, Ryhall, in the county of Rutland, the county of London, widow. carpenter and storekeeper. Robert Baily, late Clophill House, Clophill, Bedford- Herbert Ernest Avery, Whitchurch Inn, Tavistook, in shire, but whose present address the Petitioning the county of Devon, licensed victualler. Creditor is unable to ascertain. Harry Hedley Bush, the Queen's Head Hotel, Tavistock Edith Jane Spooner, formerly 12 Kimbolton Avenue, in the county of Devon, gentleman, of no occupation. Kimbolton Road, Bedford, Bedfordshire, but now Thomas Jones, 44 Dyfodwg Street, Treorky, Glamorgan, residing at 21 Fellbrigge Road, Seven Kings, Essex, miner. spinster. Thomas Watkins, 111 Tallis Street, Cwmpark, near Thomas Edward Beardsmore, Roslyn, Chessetts Wood, Treorky, Glamorgan, coal miner. Hockley Heath, in the county of Warwick, silversmith. -

Northern Rail Limited 19Th SA- Draft Agreement

NINETEENTH SUPPLEMENTAL AGREEMENT between NETWORK RAIL INFRASTRUCTURE LIMITED and NORTHERN RAIL LIMITED _____________________________________ relating to the Expiry Date of the Track Access Contract and to Schedule 3 and 5 of the Track Access Contract (Passenger Services) dated 6 January 2010 _____________________________________ 343955 THIS NINETEENTH SUPPLEMENTAL AGREEMENT is dated 2013 and made between: (1) NETWORK RAIL INFRASTRUCTURE LIMITED, a company registered in England under company number 02904587, having its registered office at Kings Place, 90 York Way, London N1 9AG ("Network Rail"); and (2) NORTHERN RAIL LIMITED, a company registered in England and Wales under company number 04619954, having its registered office at Serco House, 16 Bartley Wood Business Park, Bartley Way, Hook, Hampshire, RG27 9UY (the "Train Operator"). Background: (A) The parties entered into a Track Access Contract (Passenger Services) dated 6 January 2010 as amended by various supplemental agreements (which track access contract as subsequently amended is hereafter referred to as the "Contract"). (B) The parties propose to enter into this Supplemental Agreement in order to amend the Expiry date of the Contract and to amend the wording in Schedule 3 : Collateral Agreements to take account of the new franchise agreement and to amend Schedule 5 of the Contract to the latest Model Clause format. IT IS HEREBY AGREED as follows: 1. INTERPRETATION In this Supplemental Agreement: 1.1 Words and expressions defined in and rules of interpretation set out in the Contract shall have the same meaning and effect when used in this Supplemental Agreement except where the context requires otherwise. 1.2 “Effective Date” shall mean 1.2.1 the date upon which the Office of Rail Regulation issues its approval pursuant to section 22 of the Act of the terms of this Supplemental Agreement. -

Reception Boys Position Name School 1 Joey Hall 2 3 Matthew

Ghyll Royd Cross Country Reception Boys Position Name School 1 Joey Hall Ghyll Royd 2 Jack Dobson Ben Rhyding 3 Matthew Priestley Sacred Heart 4 Henry Cesardesa Burley Woodhead 5 Jared Richman Burley Woodhead 6 Kristian Holdsworth Burley Woodhead 7 Harry Johns Sacred Heart 8 Stanley Bannister Westville 9 Archie Budding Burley Woodhead 10 Nicholas Archer All Saints 11 Henry Smith Burley Woodhead 12 Duncan Shern Ben Rhyding 13 Jack Roberts Burley Woodhead 14 Thomas Dixon Guiseley Infants 15 Henry Riley-Smith Westville 16 James Loxton Ashlands 17 Oliver White Burley Woodhead 18 Jonathon Archer All Saints 19 Oscar Stainton All Saints 20 Freddie Wood Burley Woodhead 21 George Beasant Sacred Heart 22 Joshua Halsted Ghyll Royd 23 Ben Clarke Guiseley Infants 24 Luca Borg Ashlands 25 Eddie Weston Guiseley Infants 26 William Holley Burley Woodhead 27 Sam Brooks Burley Woodhead 28 Joshua Pearce Ashlands 29 Umar Faisal Guiseley Infants 30 Fraser Parkinson Ashlands 31 James Sterling All Saints 32 Oliver Webster Guiseley Infants 33 Billy Henderson Burley Woodhead 34 James Allenby Sacred Heart 35 Conor Dutton Guiseley Infants 36 37 Dylan Shin Burley Woodhead Team 1st Burley Woodhead 24 points 2nd Sacred Heart 65 points 3rd All Saints 78 points 4th Guiseley Infants 90 points 5th Ashlands 98 points Ghyll Royd Cross Country Year 1 Boys Position Name School 1 Edward Westlake Ghyll Royd 2 Jake Rochford Sacred Heart 3 Oscar Gilroy Bewell All Saints 4 Tom Threlfall All Saints 5 Elliot Peart Guiseley Infants 6 Thomas Campbell Burley Woodhead 7 Oliver Tuggey -

Collections Guide 2 Nonconformist Registers

COLLECTIONS GUIDE 2 NONCONFORMIST REGISTERS Contacting Us What does ‘nonconformist’ mean? We recommend that you contact us to A nonconformist is a member of a religious organisation that does not ‘conform’ to the Church of England. People who disagreed with the book a place before visiting our beliefs and practices of the Church of England were also sometimes searchrooms. called ‘dissenters’. The terms incorporates both Protestants (Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Independents, Congregationalists, Quakers WYAS Bradford etc.) and Roman Catholics. By 1851, a quarter of the English Margaret McMillan Tower population were nonconformists. Prince’s Way Bradford How will I know if my ancestors were nonconformists? BD1 1NN Telephone +44 (0)113 393 9785 It is not always easy to know whether a family was Nonconformist. The e. [email protected] 1754 Marriage Act ordered that only marriages which took place in the Church of England were legal. The two exceptions were the marriages WYAS Calderdale of Jews and Quakers. Most people, including nonconformists, were Central Library therefore married in their parish church. However, nonconformists often Northgate House kept their own records of births or baptisms, and burials. Northgate Halifax Some people were only members of a nonconformist congregation for HX1 1UN a short time, in which case only a few entries would be ‘missing’ from Telephone +44 (0)1422 392636 the Anglican parish registers. Others switched allegiance between e. [email protected] different nonconformist denominations. In both cases this can make it more difficult to recognise them as nonconformists. WYAS Kirklees Central Library Where can I find nonconformist registers? Princess Alexandra Walk Huddersfield West Yorkshire Archive Service holds registers from more than a HD1 2SU thousand nonconformist chapels. -

The Old Filter Station, Green Lane, Burley Woodhead Asking Price for £1,650,000 the Old Filter Station Green Lane Burley Woodhead LS29 7BA

The Old Filter Station, Green Lane, Burley Woodhead Asking Price For £1,650,000 The Old Filter Station Green Lane Burley Woodhead LS29 7BA A METICULOUSLY DESIGNED AND CONTEMPORARY CONVERSION OF A FORMER WATER FILTER STATION, PROVIDING STYLISHLY APPOINTED ACCOMMODATION OF IMPECCABLE QUALITY, OCCUPYING A FANTASTIC SECLUDED SETTING ALONG A PRIVATE ROAD WITH UNRIVALLED AND UNINTERRUPTED PANORAMIC VIEWS OVER THE WHARFE VALLEY. Occasionally, a property of exceptional quality comes to the market and the sale of The Old Filter Station is a perfect example. This conversion has been a labour of love for the current owners and has been designed and fitted with exacting standards and will particularly appeal to those seeking high quality modern living with luxury very much in mind. No stone has been left unturned with the conversion of this former water filter station which includes underfloor heating throughout, the latest in high speed internet technology, integrated Sonos sound systems, audio visuals and communications, as well as high top of the range finishes in bathroom and en suite facilities, with Duravit fittings and Hangrohe tropical rain showers throughout. BURLEY WOODHEAD Burley Woodhead is a hamlet located just a short drive from Ilkley town centre which offers an excellent range of high class shops, restaurants, cafes and everyday amenities including two supermarkets, health centre, playhouse and library. The town benefits from high achieving schools for all ages including Ilkley Grammar School and three sought after private schools all within a short drive. There are good sporting and recreational facilities. Situated within the heart of the Wharfe Valley, surrounded by the famous Moors to the south and the River Wharfe to the north, Ilkley is regarded as an ideal base for the Leeds/Bradford commuter. -

COLLECTIONS GUIDE 10 the First World War

COLLECTIONS GUIDE 10 The First World War Contacting Us We recommend that you contact us to book a place before visiting our searchrooms. WYAS Bradford Margaret McMillan Tower Prince’s Way Bradford BD1 1NN Telephone +44 (0)113 393 9785 e. [email protected] WYAS Calderdale Central Library Northgate House Northgate This guide provides an introductory outline to some of the Halifax HX1 1UN fascinating collections we hold relating to the First World Telephone +44 (0)1422 392636 War. e. [email protected] Although we have thoroughly searched our holdings, please WYAS Kirklees note that this list is not exhaustive and that there may be Central Library Princess Alexandra Walk more information to be found on the First World War in local Huddersfield authority, school, charity and church collections. HD1 2SU Telephone +44 (0)1484 221966 If you would like to know more about West Yorkshire Archive e. [email protected] Service, please check our website at WYAS Leeds Nepshaw Lane South www.archives.wyjs.org.uk or visit our offices in Bradford, Leeds LS27 7JQ Calderdale (Halifax), Kirklees (Huddersfield), Leeds and Telephone +44 (0)113 3939788 e. [email protected] Wakefield. (see the last page of this guide for further information) WYAS Wakefield West Yorkshire History Centre 127 Kirkgate Wakefield To find out more about these documents check our online WF1 1JG e. [email protected] collections catalogue at http://catalogue.wyjs.org.uk/ (The number in brackets at the start of each entry is the catalogue finding number) 09/02/2017 1 Documents held at WYAS, Bradford War Memorials and Rolls of Honour (15D92) 1922 Programme for the unveiling of the Bradford War Memorial The War Memorial was unveiled on Saturday 1 July 1922. -

16 October 2019 Year 5

Keighley & Craven Schools Cross Country League 2019 - 2020 Year 5 - 6 Girls Cliffe Castle 16 October 2019 Race Pupil Number Number Pupil Name School Year Group 1 BR04 Isabella Wright Bradley Both 6 2 SIL05 Isobel Patefield Silsden 5 3 BR10 Jessica Anderson Bradley Both 5 4 NE01 Macey Plunket Nessfield 5 5 BW06 Courtney O'Connor Burley Woodhead 5 6 BUR03 Amy Gordon Burley Oaks 5 7 OX19 Sophia Casson Oxenhope 6 8 SIL02 Holly Fitch Silsden 5 9 BUR04 Dolly Gordon Burley Oaks 5 10 BUR11 Isla Arundel Burley Oaks 5 11 LL22 Tara Miller Long Lee 6 12 STAN03 Maizie Booth Stanbury 5 13 STAN01 Isla Eastham Stanbury 5 14 OA61 Lily Arnold Oakworth 5 15 BUR05 Millie Porteous Burley Oaks 5 16 STAN02 Neve Garbutt Stanbury 5 17 PW06 Afeefa Shah Parkwood 6 18 EB24 Claire Edwards Eastburn 5 19 HA10 Floss Andrews Haworth 5 20 HOL11 Megan Taylor-Chester Holycroft 5 21 STAN07 Tilly Thornton Stanbury 5 22 SIL122 Brooke Binns Silsden 5 23 LEE06 Erin Carter Lees 5 24 CW04 Liberty Wood Cullingworth 6 25 OX11 Lillie Alborne Oxenhope 6 26 CW06 Maisy Padgett Cullingworth 5 27 STAN14 Ava Sollitt Stanbury 5 28 LL10 Kaya Medica Long Lee 6 29 HA47 Ellie-May Varley Haworth 5 30 OA46 Tanya Rashid Oakworth 5 31 SIL40 Robyn Horton Silsden 5 32 SIL47 Mary Wilson Silsden 5 33 PW05 Grace Prescott Rose Parkwood 6 34 OA92 Isabella Charmbury Oakworth 6 35 EA05 Eliza Abdullah Eastwood 5 36 BR06 Holly Hampshire Bradley Both 6 37 SIL04 Umayma Saddique Silsden 5 38 EM24 L Holt East Morton 6 39 SIL36 Thea Newby Silsden 5 40 CW07 Lyla Illingworth Cullingworth 5 41 EM30 E Rogers East