Reflections 16.2.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

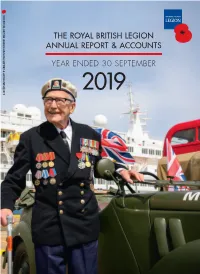

2019 Annual Report

THE ROYAL BRITISH LEGION ANNUAL REPORTTHE ROYAL 2019 & ACCOUNTS THE ROYAL BRITISH LEGION ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS YEAR ENDED 30 SEPTEMBER 2 019 Cover.indd 1 04/06/2020 14:36 ROYAL BRITISH LEGION ANNUAL REPORT • 2019 COVER 210X297 84 3MM Contents.indd 2 04/06/2020 16:19 ROYAL BRITISH LEGION ANNUAL REPORT • 2019 CONTENTS 210X297 84 3MM CONTENTS FOREWORD P4 TRUSTEES’ REPORT P6 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT P50 STATEMENTS OF FINANCIAL ACTIVITIES P52 BALANCE SHEETS P54 CASH FLOW STATEMENTS P55 NOTES TO THE ACCOUNTS P56 Contents.indd 3 04/06/2020 16:19 ROYAL BRITISH LEGION ANNUAL REPORT • 2019 CONTENTS 210X297 84 3MM FOREWORD the fallen. Voice recordings of veterans from the Imperial War Museum’s archive played as the audience stood in silence holding photos of Service personnel from the First World War who never came home. We were delighted when the Festival won its first-ever BAFTA, for Best Live Event. Driven by huge public interest stimulated by commemorations of the end of the First World War, the Poppy Appeal that began in 2018 and closed in 2019 raised almost £55 million, more than any appeal in our history. Once again, we are genuinely humbled by the support we receive and the dedication of our members and volunteers, both during the Poppy Appeal and throughout the year. UNA CLEMINSON, National Chairman and CHARLES BYRNE, Director General While it has been uplifting to see so many people from different backgrounds and nationalities brought together at our events, we do not forget A year that saw the 75th anniversary people from different backgrounds unite those who feel isolated. -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

Humberside Police Concert Band

Souveni Edition Programme £3.50 ARE YOU CURRENTLY SERVING IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE OR HAVE YOU SERVED Then come along to the Grimsby & Cleethorpes Branch and Club of the Royal Air Forces Association Membership available...Enjoy a warm welcome 5 Alexandra Road, Cleethorpes, North East Lincolnshire Telephone: 07904 228477 The Cross Keys Grasby Fine Ales, Good Food, Great Pub Welcome... The aim of all at The Cross Keys is to make our guests feel welcome & comfortable. Offering a range of well kept ales, excellent food using locally sourced produce (wherever and whenever possible), a relaxed yet efficient approach to service & a warm & friendly atmosphere. A complete experience not to be rivalled in this beautiful rural setting with stunning views across the Lincolnshire Wolds. The Cross Keys are proud to support Armed Forces Weekend in North East Lincolnshire – and have donated meals for the Band of the Brigade Of Gurkhas Contents REVIEWING OFFICER 4 THE QUEEN’S DIAMOND JUBILEE 13 GUEST VIP 5 RAF FALCONS PARACHUTE DISPLAY TEAM 16 PRESENTER AND COMMENTATOR 6 ROYAL AIR FORCE WADDINGTON PIPES AND DRUMS 17 MUSIC PROGRAMME 2012 7 MILITARY WIVES CHOIRS 18 PRODUCER AND EVENT MANAGER 8 BAND OF THE BRIGADE OF GURKHAS 19 JOINT PRODUCER 8 HUMBERSIDE POLICE DOG DISPLAY TEAM 20 SHOW DIRECTOR 9 HUMBERSIDE POLICE CONCERT BAND 21 ASSISTANT SHOW DIRECTOR 9 BAND OF THE ROYAL AIR FORCE COLLEGE 22 EVENT SECURITY/EVENT CONTROL 10 THE ROYAL SIGNALS WHITE HELMETS 23 SITE MANAGER 10 THE LONE PIPER 24 HEALTH AND SAFETY EVENT CONTROLLER 11 FRONTIER FIREWORKS 24 MINUTE -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

i “NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT” – EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA Stephen Leslie Wilks, September 2017 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University © Copyright by Stephen Leslie Wilks, 2017 All Rights Reserved ii DECLARATION This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any tertiary institution, and, to the best of my knowledge, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. …………………………………………. Stephen Wilks September 2017 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This is a study of the ideas held by an intelligent, dedicated, somewhat eccentric visionary, and of his attempts to shape the young Australian nation. It challenges, I hope convincingly, misconceptions about Earle Page. It sets him in wider context, both in terms of what was happening around him and of trying to interpret the implications his career has for Australia’s history. It contributes to filling a gap in perceptions of the Australian past and may also have relevance for to-day’s political environment surrounding national development policy. Thanks foremostly and immensely to Professor Nicholas Brown of the Australian National University School of History, my thesis supervisor and main guide who patiently read and re-read drafts in order to help make this a far better thesis than it could ever have been otherwise. Thanks also to supervisory panel members Frank Bongiorno, Peter Stanley and Linda Botterill; staff and students of the ANU School of History including those in the National Centre of Biography; and Kent Fedorowich of the University of the West of England. -

The Royal British Legion Annual Report & Accounts

THE ROYAL BRITISH LEGION ANNUAL REPORTTHE ROYAL 2017 & ACCOUNTS THE ROYAL BRITISH LEGION ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS YEAR ENDED 30 SEPTEMBER 2 017 Cover.indd 1 01/05/2018 10:10 ROYAL BRITISH LEGION ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 001_COVER_V2 210X297 84 Contents_and_Forward.indd 2 26/04/2018 12:27 ROYAL BRITISH LEGION ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 002_CONTENTS + WELCOME_V1 210X297 84 CONTENTS Foreword 4 Financial overview 6 Trustees’ report 10 Independent auditor’s report 48 Statements of financial activities 52 Balance sheets 54 Cash flow statements 55 Notes to the accounts 56 3 Contents_and_Forward.indd 3 26/04/2018 12:27 ROYAL BRITISH LEGION ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 003_CONTENTS + WELCOME_V1 210X297 84 FOREWORD annual meeting: we want to become a ‘team of teams’. Support takes many forms. The inspirational strength and determination of today’s Armed Forces community were on full display at the Invictus Games in Toronto, where we hosted 260 family members of those competing. The Legion’s campaigning work, ensuring that Government policy and services consider the needs of our Armed Forces personnel and their families, is another way we offer support. Our Count Them In campaign has also CHARLES BYRNE, Director General and TERRY WHITTLES, National Chairman ensured that the Office for National Statistics (ONS) will recommend a This review gives us an opportunity challenge. The Royal British Legion new question about the Armed Forces to step back and remind ourselves of led a consortium of service charities community be included in the next why we’re here. The Royal British to bid for and win the contract to census in England and Wales. -

History of the California Cadet Corps As Viewed Through Primary Source Documents 1911-2014

History of the California Cadet Corps As Viewed Through Primary Source Documents 1911-2014 California Military Department Headquarters, California Cadet Corps 1 July 2014 History of the California Cadet Corps As Viewed Through Primary Source Documents 1911-2014 Contents HISTORY OF THE CALIFORNIA CADET CORPS: Circa 1951 ......................................................... 1 REPORT OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL OF CALIFORNIA: July 1, 1910, to November 16, 1914 .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 REPORT OF THE ADJUDANT GENERAL OF CALIFORNIA: November 17, 1914, to June 30, 1920 .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 REPORT OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL OF CALIFORNIA: July 1, 1920, to .June 30, 1926 .. 11 REPORT OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL OF CALIFORNIA: July 1, 1926, 10 June 30, 1928 .. 12 REPORT OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL OF CALIFORNIA: July 1, 1928, 10 June 30, 1930 .. 14 REPORT OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL OF CALIFORNIA: July 1 1930, to June 30, 1932 .... 16 REPORT ON ACTIVITIES FOR 1946 AND OF THE ANNUAL ENCAMPMENT AT FORT ORD, CALIFORNIA: July 1 to July 12, 1946 .................................................................................................. 18 The Adjutant General’s Message ...................................................................................................... 18 The Cadet Corps -

Government Records About the Australian Capital Territory Government Records About the Australian Capital Territory

Government Records about the Australian Capital Territory Australian Capital the Records about Government Government Records about the Australian Capital Territory Ted Ling Ted Ling Ted Research guide Government Records about the Australian Capital Territory Ted Ling National Archives of Australia © Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia) 2013 This product, excluding the National Archives of Australia logo, Commonwealth Coat of Arms and any material owned by a third party or protected by a trademark, has been released under a Creative Commons BY 3.0 (CC–BY 3.0) licence. Excluded material owned by third parties may include, for example, design and layout, images obtained under licence from third parties and signatures. The National Archives of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify and label material owned by third parties. You may distribute, remix and build on this work. However, you must attribute the National Archives of Australia as the copyright holder of the work in compliance with its attribution policy available at naa.gov.au/copyright. The full terms and conditions of this licence are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au. Inquiries relating to copyright should be emailed to [email protected]. Images that appear in this book are reproduced with permission of the copyright holder. Every reasonable endeavour has been made to locate and contact copyright holders. Where this has not proved possible, copyright holders are invited to contact the publisher. This guide is number 25 in the series of research guides published by the National Archives. Guides include the material known to be relevant to their subject area but they are not necessarily a complete or definitive guide to all relevant material in the collection.