Motivations for Compliance in Peruvian Manta Ray Fisheries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brochure Atlantic Forest Great Reserve

Atlantic Forest Barra do Ararapira Paraná peak Rafting Mãe Catira River Mountain bike THE ATLANTIC FOREST: PROTECTED AREAS AND FULL NATURE MOUNTAINS AND FOREST A NATURAL AND CULTURAL SPECTACLE The Full Nature framework considers every year. In this view, new businesses The Atlantic Forest express its exuber- the existence of fruits to feed the fauna. The Atlantic Forest is one of the most diversity of wildlife, mountains, caves, the ecological integrity and the peace- have been established. However, not all ance in different landscapes: the pre- The rain is abundant, and thousands exuberant tropical forests in the world. waterfalls, bays, mangroves and beaches, ful coexistence between society and the activities take into consideration nature historic Araucaria Forest, mountains of rivers generated in the cradle of this Within its territory, this biome holds as well as local communities. It is up to natural environments as the basis for a conservation. Full Nature framework and rivers, the coastal plain and the sea. great forest carve the mountains and natural and cultural treasures, some of us to protect this treasure from the risk green and restorative economy, espe- was designed as a unifying cause to en- There are over15,000 species of plants give us beautiful waterfalls. A collection Brazil’s largest cities, and over 120 mil- of disappearance. cially in isolated and disadvantaged ru- sure that development is equitable and and more than 2,000 species of verte- of peaks and hills challenges the climb- lion inhabitants. Brazilian history was The economic development in this ral areas. Nature conservation should long lasting. -

“Queen Without Land” (Polar Bears) Recommended for Grades 5-7

Queen without Land “Queen without Land” (Polar Bears) Recommended for grades 5-7 Your class is going to watch the documentary “Queen without Land” on September 29, 2018. This folder contains some exercises that will help you prepare for it. Have fun! page 1 page 2 Queen without Land Wildlife films are sooooo boring...?! Here are why you should watch this film! The filmmaker Asgeir Helgestad follows a polar bear mother and her cubs. Who wouldn’t like to see cute animal babies playing in the snow? There are some scenes in which the filmmaker is filming himself while he uses his high-tech cameras and other cool equipment. It’s really fun to see how the film was made. The film is set on Svalbard, an island group between Norway and the North Pole. You’ll see how Asgeir Helgestad lives there, in the freezing cold. The filmmaker shows exactly how global warming changes the ice around the North Pole, the animals who live in the Arctic, and the plants that grow there. You’ll also learn what consequences global warming has for you personally. It’s an award-winning film. The film won the award for Best Environmental Film at the International Wildlife Film Festival. page 3 Documentary - a special genre Why should I learn something about documentaries? Soon, your class is going to watch “Queen without Land” (Polar Bears). Just like in any other type of film, such as action films or Youtube vlogs, the filmmakers use camera settings, music, and other things to tell a story. -

Scientific Committee Sixteenth Regular Session

SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE SIXTEENTH REGULAR SESSION ELECTRONIC MEETING 11{20 August 2020 Data review and potential assessment approaches for mobulids in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean WCPFC-SC16-2020/SA-IP-12 Laura Tremblay-Boyer1, Katrin Berkenbusch1 1Dragonfly Data Science, Wellington, New Zealand Data review and potential assessment approaches for mobulids in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean Report prepared for The Pacific Community Authors: Laura Tremblay-Boyer Katrin Berkenbusch PO Box 27535, Wellington 6141 New Zealand dragonfly.co.nz Cover Notes To be cited as: Tremblay-Boyer, Laura; Berkenbusch, Katrin (2020). Data review and potential assess- ment approaches for mobulids in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, 55 pages. Report prepared for The Pacific Community. Cover image: hps://www.flickr.com/photos/charleschandler/6126361915/ CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 1 INTRODUCTION ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 2 METHODS ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 2.1 Summary of fishery data ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 2.2 Literature review of mobulid biology ----------------------------------------------------------- 12 2.3 Appraisal of potential assessment approaches ------------------------------------------ 12 3 RESULTS -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Elasmobranch Captures in the Fijian Pelagic Longline Fishery

AQUATIC CONSERVATION: MARINE AND FRESHWATER ECOSYSTEMS Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. (2016) Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/aqc.2666 Elasmobranch captures in the Fijian pelagic longline fishery SUSANNA PIOVANOa,* and ERIC GILMANb aThe University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji bHawaii Pacific University, Honolulu, USA ABSTRACT 1. Pelagic longline fisheries for relatively fecund tuna and tuna-like species can have large adverse effects on incidentally caught species with low-fecundity, including elasmobranchs. 2. Analyses of observer programme data from the Fiji longline fishery from 2011 to 2014 were conducted to characterize the shark and ray catch composition and identify factors that significantly explained standardized catch rates. Catch data were fitted to generalized linear models to identify potentially significant explanatory variables. 3. With a nominal catch rate of 0.610 elasmobranchs per 1000 hooks, a total of 27 species of elasmobranchs were captured, 48% of which are categorized as Threatened under the IUCN Red List. Sharks and rays made up 2.4% and 1.4%, respectively, of total fish catch. Blue sharks and pelagic stingrays accounted for 51% and 99% of caught sharks and rays, respectively. 4. There was near elimination of ‘shark lines’, branchlines set at or near the sea surface via attachment directly to floats, after 2011. 5. Of caught elasmobranchs, 35% were finned, 11% had the entire carcass retained, and the remainder was released alive or discarded dead. Finning of elasmobranchs listed in CITES Appendix II was not observed in 2014. 6. There were significantly higher standardized shark and ray catch rates on narrower J-shaped hooks than on wider circle hooks. -

Mobulid Rays) Are Slow-Growing, Large-Bodied Animals with Some Species Occurring in Small, Highly Fragmented Populations

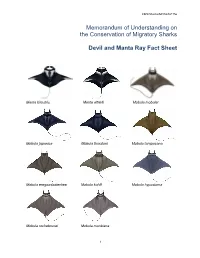

CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks Devil and Manta Ray Fact Sheet Manta birostris Manta alfredi Mobula mobular Mobula japanica Mobula thurstoni Mobula tarapacana Mobula eregoodootenkee Mobula kuhlii Mobula hypostoma Mobula rochebrunei Mobula munkiana 1 CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e . Class: Chondrichthyes Order: Rajiformes Family: Rajiformes Manta alfredi – Reef Manta Ray Mobula mobular – Giant Devil Ray Mobula japanica – Spinetail Devil Ray Devil and Manta Rays Mobula thurstoni – Bentfin Devil Ray Raie manta & Raies Mobula Mobula tarapacana – Sicklefin Devil Ray Mantas & Rayas Mobula Mobula eregoodootenkee – Longhorned Pygmy Devil Ray Species: Mobula hypostoma – Atlantic Pygmy Devil Illustration: © Marc Dando Ray Mobula rochebrunei – Guinean Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula munkiana – Munk’s Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula kuhlii – Shortfin Devil Ray 1. BIOLOGY Devil and manta rays (family Mobulidae, the mobulid rays) are slow-growing, large-bodied animals with some species occurring in small, highly fragmented populations. Mobulid rays are pelagic, filter-feeders, with populations sparsely distributed across tropical and warm temperate oceans. Currently, nine species of devil ray (genus Mobula) and two species of manta ray (genus Manta) are recognized by CMS1. Mobulid rays have among the lowest fecundity of all elasmobranchs (1 young every 2-3 years), and a late age of maturity (up to 8 years), resulting in population growth rates among the lowest for elasmobranchs (Dulvy et al. 2014; Pardo et al 2016). 2. DISTRIBUTION The three largest-bodied species of Mobula (M. japanica, M. tarapacana, and M. thurstoni), and the oceanic manta (M. birostris) have circumglobal tropical and subtropical geographic ranges. The overlapping range distributions of mobulids, difficulty in differentiating between species, and lack of standardized reporting of fisheries data make it difficult to determine each species’ geographical extent. -

State of Hawaii DEPARTMENT of LAND and NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation Honolulu, Hawaii 96819

State of Hawaii DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation Honolulu, Hawaii 96819 May 28, 2021 Chairperson and Members Board of Land and Natural Resources State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaiʻi Land Board Members: SUBJECT: Request approval to install a total of twenty-three new day-use mooring buoys at the Makako Bay and Kaukalaelae Point manta ray viewing sites in West Hawaiʻi; approval of an Anticipated Finding of No Significant Impact for the Draft Environmental Assessment applicable to the installation of the twenty-three mooring buoys; and delegation of authority to the Chairperson to make a final determination on the Draft Environmental Assessment. REMARKS: In the 2014 Legislative Session, the Hawaiʻi House of Representatives passed House Concurrent Resolution 170 urging the Department to manage the Kona manta ray viewing sites and address overcrowding, safety, and liability under existing statutes. DOBOR consulted with stakeholders, such as ocean tour providers and recreational ocean users, and devised a list of proposed rules and management measures for the sites, including the installation of additional moorings to increase safety. The arrangement of DMBs at the two sites will offset negative impacts of anchoring on coral reef habitat, minimize unsafe boating practices near participants in-water, and control crowding at the site by requiring use of a mooring to conduct tours. Thus, the Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation (DOBOR) is requesting that the Board of Land and Natural Resources (Board) approve the installation of twenty-three (23) new day-use mooring buoys (DMBs) in Makako Bay and Kaukalaelae Point of North Kona in West Hawaiʻi. -

CRFM RESEARCH PAPER COLLECTION. Volume 6

CRFM Research Paper Collection Volume 6 CRFM Secretariat Belize i CRFM RESEARCH PAPER COLLECTION. Volume 6 © CRFM 2012 All right reserved. Reproduction, dissemination and use of material in this publication for educational or noncommercial purposes are authorized without prior written permission of the CRFM, provided the source is fully acknowledged. No part of this publication may be reproduced, disseminated or used for any commercial purposes or resold without the prior written permission of the CRFM. ISSN # 1995-4840 ISBN # 978-976-8165-67-1 Published by the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism Secretariat, Belize ii CONTENTS Ferrier, E. and Singh- Stakeholder Preferences for Regional Management Objectives: A 1 Renton, S. Case of the Flyingfish Fishery of Barbados and Tobago Campbell, B. and Singh- Towards an Ecosystem Approach for Flyingfish Fisheries in the Renton, S. Eastern Caribbean: An Evaluation of Multi-Criteria Analysis as a 39 Tool for Improving Information in Multi-Objective Decision-Making Proudfoot, M. and Exploring the Use of an Ecological Risk Assessment Tool for Singh-Renton, S. Management of the Large Pelagic Fishery in the Eastern Caribbean 75 iii CRFM Research Paper Collection Vol. 6 STAKEHOLDER PREFERENCES FOR REGIONAL MANAGEMENT OBJECTIVES: A CASE OF THE FLYINGFISH FISHERY OF BARBADOS AND TOBAGO Elaine Ferrier1, and Susan Singh-Renton2 1CIDA Intern, Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia, Canada, Email: [email protected] 2Deputy Executive Director, CRFM Secretariat, Halifax Street, Kingstown, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Email: [email protected] Abstract This study is an application of a pairwise comparison technique to determine weighted rankings of objectives for regional management of the Flyingfish fishery. -

Shark Fishing in the Indian Seas: a Quantitative Risk Assessment of the Impacts of Longline Fishing on the Sustainability of Regional Shark Populations

Shark Fishing in the Indian Seas: A Quantitative Risk Assessment of the Impacts of Longline Fishing on the Sustainability of Regional Shark Populations The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagle, Christopher H. 2019. Shark Fishing in the Indian Seas: A Quantitative Risk Assessment of the Impacts of Longline Fishing on the Sustainability of Regional Shark Populations. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004165 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Shark Fishing in the Indian Seas: A Quantitative Risk Assessment of the Impacts of Longline Fishing on the Sustainability of Regional Shark Populations Christopher H. Nagle A Thesis in the Field of Sustainability and Environmental Management for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2018 Copyright 2018 Christopher H. Nagle Abstract This project endeavored to provide a formative, contemporaneously applicable, and fully quantitative baseline of a significant component of the shark harvest produced by the nation of India, namely, the longline bycatch mortality for sharks generated from the commercial-scale fishing activity in the extensive oceanic region of India’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), the nature and scope of which is little understood. Worldwide, shark populations have experienced marked declines due to the advent of modern industrial fishing. -

Manta Birostris in the Indian Ocean

Biological Aspects, Stock and Conservation Status of Giant Title Oceanic Manta Ray, Manta birostris in the Indian Ocean Author(s) DHARMADI; FAHMI PROCEEDINGS of the Design Symposium on Conservation of Citation Ecosystem (The 13th SEASTAR2000 workshop) (2014), 2: 1-8 Issue Date 2014-03 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/185137 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Biological Aspects, Stock and Conservation Status of Giant Oceanic Manta Ray, Manta birostris in the Indian Ocean(*) DHARMADI1) & FAHMI2) 1) Research Center for Fisheries Management and Conservation, Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries. Jl. Pasir Putih I, Ancol Timur Jakarta 14430 Indonesia 2) Research Center for Oceanography-Indonesian Institute of Sciences Email: [email protected];[email protected] ABSTRACT The giant oceanic manta ray (Manta birostris) is a ray species of the Family Mobulidae, the largest type of rays in the world. A study on Manta rays from the Indian Ocean was conducted from April 2001 to August 2005 at Cilacap-Central Java and Tanjungluar-East Lombok fish landings. Catch data of Cilacap fishing port from 2006 to 2011 are also presented in this paper. The methodology utilized was direct observations and data collection by enumerators. The results show that Manta rays were caught as by-catch of tuna gillnet and tuna longline fishing in the Indian Ocean. There were three age groups (cohorts) of the Manta birostris caught in the Indian Ocean, i.e. size class between 200-300 cm disc width (DW) as a young group, 301-400 cm DW (subadult group), and 401-500 cm DW (adult group), respectivelly. -

The State of Nearshore Marine Habitats in the Wider Caribbean

2020 The State of Nearshore Marine Habitats in the Wider Caribbean United Nations Environment Programme - Caribbean Environment Programme (UNEP-CEP) Caribbean Natural Resources Institute (CANARI), Technical Report No. 00 Title of the Report Authors of the Report Partner’s Name, Technical Report No.00 Catalyzing implementation of the Strategic Action Programme for the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf LME’s (2015-2020) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Development of this Information Product and its contents, and/or the activities leading thereto, have benefited from the financial support of the UNDP/GEF Project: “Catalysing Implementation of the Strategic Action Programme (SAP) for the Sustainable Management of shared Living Marine Resources in the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf Large Marine Ecosystems” (CLME+ Project, 2015-2020) The CLME+ Project is executed by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) in close collaboration with a large number of global, regional and national-level partners. All are jointly referred to as the “CLME+ Project co- executing partners”. www.clmeproject.org [email protected] As a GEF Agency, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) implements a global portfolio of GEF co-funded Large Marine Ecosystem projects, among which the CLME+ Project. www.undp.org Through the International Waters (IW) focal area, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) helps countries jointly manage their transboundary surface water basins, groundwater basins, and coastal and marine ecosystems. www.thegef.org UNOPS mission is to serve people in need by expanding the ability of the United Nations, governments and other partners to manage projects, infrastructure and procurement in a sustainable and efficient manner. www.unops.org _______________________ CLME+ Project Information Products are available on the CLME+ Hub (www.clmeplus.org) and can be downloaded free of cost. -

Urban Manta Rays: Potential Manta Ray Nursery Habitat Along a Highly Developed Florida Coastline

Vol. 43: 51–64, 2020 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published September 3 https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01054 Endang Species Res OPEN ACCESS Urban manta rays: potential manta ray nursery habitat along a highly developed Florida coastline Jessica H. Pate*, Andrea D. Marshall Marine Megafauna Foundation, Truckee, CA, 96161, USA ABSTRACT: The giant oceanic manta ray Mobula birostris was listed in the US Endangered Spe- cies Act as a threatened species in 2018, yet insufficient data exist on manta populations through- out US waters to designate critical habitat. Taxonomic and genetic evidence suggests that manta rays in the Western Atlantic are a separate species (M. cf. birostris) and little is understood about the ecology and life history of this putative species. The juvenile life stage of both M. birostris and M. cf. birostris is particularly understudied. Here, we are the first to describe the characteristics of a manta ray population along a highly developed coastline in southeastern Florida using boat- based surveys and photo identification of individuals. Fifty-nine manta individuals were identified between 2016 and 2019. All males were sexually immature based on clasper development, and 96% of females were classified as immature based on size and absence of mating scars or visible pregnancies. Twenty-five (42%) individuals were observed more than once during the study period and 8 individuals were sighted over multiple years. The occurrence of juveniles, high site fidelity and extended use of the study area by juvenile manta rays suggest that southeastern Florida may serve as a nursery habitat. High occurrence of fishing line entanglement (27% of individuals) and vessel strike injury were documented, and rapid wound healing was observed. -

2020 SAFE Report

2020 Stock Assessment and Fishery Evaluation Report ATLANTIC HIGHLY MIGRATORY SPECIES MARCH 2021 U.S. Department of Commerce | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | National Marine Fisheries Service Atlantic Highly Migratory Species | SAFE REPORT For HMS Permitting Information and Regulations • HMS recreational fishermen, commercial fishermen, and dealer compliance guides: www.fisheries.noaa.gov/ • atlantic-highly-migratory-species/atlantic-hms-fishery-compliance-guides Regulatory updates for tunas: hmspermits.noaa.gov For HMS Permit Purchase or Rewards Issuer Permits Contact Information OpenHMS Permit Access Shop Vessel Permits HMS Charter/Headboat, Atlantic Tunas (888) 872-8862 (General, Harpoon, Trap), Swordfish hmspermits.noaa.gov General Commercial, HMS Angling (recreational) Southeast Regional Office Commercial Caribbean Small Boat, (727) 824-5326 Smoothhound Shark www.fisheries.noaa.gov/southeast/ resources-fishing/southeast-fisheries- permits Greater Atlantic Regional Fisheries Office Incidental HMS Squid Trawl (978) 281-9370 www.fisheries.noaa.gov/new-england- mid-atlantic/resources-fishing/vessel-and- dealer-permitting-greater-atlantic-region LimitedIssuer Access Vessel Permits Permits Contact Information HMS Permit Shop Atlantic Tunas Purse Seine category (888) 872-8862 hmspermits.noaa.gov Southeast Regional Office Directed Shark, Incidental Shark, Directed (727) 824-5326 Swordfish, Incidental Swordfish, Atlantic www.fisheries.noaa.gov/southeast/ Tunas Longline category resources-fishing/southeast-fisheries- permits DealerIssuer Permits Permits Contact Information Greater Atlantic Regional Fisheries Office Atlantic Tunas Dealer (978) 281-9370 www.fisheries.noaa.gov/new-england- mid-atlantic/resources-fishing/vessel-and- dealer-permitting-greater-atlantic-region Southeast Regional Office Atlantic Shark Dealer and Atlantic (727) 824-5326 Swordfish Dealer www.fisheries.noaa.gov/southeast/ resources-fishing/southeast-fisheries- permits ii U.S.