Teachers and Teacher Educators Learning Through Inquiry: International Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Students Take to the Catwalk for Teenage Cancer Trust

PONTELAND • MILBOURNE • MEDBURN • PRESTWICK • KIRKLEY ISSUE 127 | APR 16 FREE monthly community magazine for Ponteland and district Headteacher’s fury at school closure plan Students take to Village to celebrate the Queen’s 90th birthday the catwalk for Beer festival returns for third year Teenage Cancer Trust www.pontelandtowncouncil.co.uk pontnews&views 1 2495 390 Thinking of retiring? Unsure of your options? Your promise of excellence, Domestic & Commercial Sales, Spares, Service & Speak to Repairs On All Types of a pensions Vacuum Cleaner expert Specialising in • ALL REPAIRS GUARANTEED • SERVICE CONTRACTS AVAILABLE Specialist for Kirby Sales & Service For your free initial consultation give us a call on (01661) 821110 or email us at [email protected] CFS Independent Financial Advisers NatWest Bank Chambers, 2 Darras Road, Ponteland, NE20 9HA Tel 0191 284 6688 CFS Independent Financial Advisers is a trading style of Connacht Financial Services www.vacattack.com Generation House, Station Road, South Gosforth, Newcastle Pont News & Views is published by Ponteland Town Council in conjunction with Ponteland Community Partnership. Inclusion of articles and advertising in Pont News & Views does not imply Ponteland Town Council’s or Ponteland Community Partnership’s endorsement, agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided. If you would like to submit an article, feature or advertise contact: T. (0191) 3408422 E. [email protected] W. Westray, 16 Sunniside Lane, Cleadon Village, SR6 7XB. 2Produced bypont Ciannews creative&views pr 07013 - Vac Attack quarter copy.indd 1 email:email: [email protected] [email protected]/6/15 09:07:47 Annabel Atkinson Cameron Bates Stylish students strut their stuff at fashion show Stylist students and staff strutted their stuff on the catwalk at a glitzy charity fashion show at Newcastle’s Biscuit Factory. -

PNV Feb 20 Issue

PONTELAND • MILBOURNE • MEDBURN • PRESTWICK • KIRKLEY ISSUE 173 | FEB 20 FREE monthly community magazine for Ponteland and district Explosive report alleges collusion over housing scheme Race aces prove a New 20mph zones launched around Ponteland schools pushover in annual “Consternation” over car park closure barrow challenge www.pontelandtowncouncil.co.uk pontnews&views 1 Belsay Woodland Burials Now Available 2650 from 2899 390 Thinking of retiring? Unsure of your options? Speak to a pensions expert For your free initial consultation give us a call on (01661) 821110 or email us at [email protected] CFS Independent Financial Advisers Limited, Lower Blyth Suite, Kirkley Hall, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE20 OAQ Pont News & Views is published by Ponteland Town Council in conjunction with Ponteland Community Partnership. Inclusion of articles and advertising in Pont News & Views does not imply Ponteland Town Council’s or Ponteland Community Partnership’s endorsement, agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided. If you would like to submit an article, feature or advertise contact: T. (0191) 5191306 E. [email protected] Westray, 16 Sunniside Lane, Cleadon Village, SR6 7XB. Produced by Cian creative pr Full speed ahead as competitors hit the track Dave Taylor and Claire Richardson close in on finish line Wheeling in the New Year for record-breaking feats They are not quite silver Conlon had to settle for the runners-up Matthew Crooks and George Hunter dream machines, but spot, despite their time of 8 mins 2 secs were second in 6 mins 44 secs and Alun being second fastest time ever recorded, Woodward and Harry Walker third in Ponteland’s annual New and three-time race winner Joanne 6 mins 46 secs. -

Consultation on Admission Arrangements to Pele Trust Schools for the 2021-22 Academic Year

Consultation on Admission Arrangements to Pele Trust schools for the 2021-22 academic year Consultation period (6 weeks) Start: 1 October 2019 End: 26 November 2019 (4.00pm) Pele Trust welcome comments on the Admissions policy proposal. Responding to the consultation Email responses to: [email protected] Written responses to: Carol Wilson, Ponteland High School, Callerton Lane, Ponteland, NE20 9EY Registered address: Callerton Lane, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne NE20 9EY. A charitable company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales (company number: 11395017. 1 Consultation on Admission Arrangements for Pele Trust schools for the 2021-22 academic year Background Pele Trust was formed on 1 February 2019 and consists of five primary schools and one secondary school: Belsay Primary; Darras Hall Primary; Heddon St. Andrews Primary; Ponteland Primary; Richard Coates CE School and Ponteland High School. Pele Trust is the Admissions Authority for each of the schools within the Trust. Due to the conversion date this is the first opportunity for the Directors to formally consult on their proposed admission arrangements and reflects their desire to ensure a reasonable, clear, objective and procedurally fair Admissions Policy that supports the aims of the Trust and serves our local community and complies with all relevant legislation. Consultation Process Admission Authorities have a duty to consult on their admission arrangements in advance of the year of intake. The School Standards and Framework Act 1998 provides the DfE with the right to issue a statutory School Admissions Code, setting out statutory guidance and imposing mandatory requirements and guidelines in relation to school admissions (known as the "Code"). -

Virtual School Teams: ESLAC, Education Welfare, EOTAS Health Needs, Schools’ Safeguarding

Back to School: September 2020 A briefing for Designated Teachers, Designated Safeguarding Leads & attendance leads What to expect from the Virtual School teams: ESLAC, Education Welfare, EOTAS Health Needs, Schools’ Safeguarding As far as possible, we are aiming for business as usual, working safely with you and our children in ways that are covid-secure • offer advice and support for re-engaging students Virtual School Virtual Training Programme 2020- in school 21 • work with other agencies to support pupils with A full virtual training programme for DTs and DSLs is concerns regarding the return to school available now for booking using the google form at • monitor and support the attendance of this link: permanently excluded pupils in alternative provision. Virtual School Training Programme 2020-21 Although we don’t yet know how parents across the EDUCATION WELFARE county will respond to mandatory school attendance, As you know, attendance at school from 1st we do know that it is more important than ever to September 2020 will once again be compulsory, with identify and monitor children at risk of missing arrangements clearly set out in the government’s education. The first monthly CME Return is due on th statutory guidance School Attendance (August 30 September, and I am encouraging all education 2020), updated to respond to the current global providers to make sure that it is completed and pandemic. submitted to [email protected] The Education Welfare team will be returning to according to Northumberland’s guidance Children ‘business as usual’ from September, in line with the missing and missing out on education (CME). -

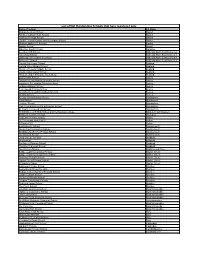

School Name Arrangement Abbeyfields First School Huggg: LA Led Voucher System Managed Through School

School Name Arrangement Abbeyfields First School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Acomb First School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Adderlane Academy Local arrangement by school Allendale Primary School Local arrangement by school Amble First School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Amble Links First School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Ashington Academy Local arrangement by school Astley Community High School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Atkinson House School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Barndale House School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Beaconhill Primary School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Beaufront First School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Bede Academy Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Bedlington Academy Local arrangement by school Bedlington Station Primary School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Bedlington Stead Lane Primary School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Bedlington West End Primary School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Bedlington Whitley Memorial C of E Primary School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Belford Primary School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Bellingham Middle School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Bellingham Primary School Local arrangement by school Belsay Primary School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Berwick Academy Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Berwick Middle School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. Bothal Primary School Local arrangement by school Branton Primary School Huggg: LA led voucher system managed through school. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Pele Trust Admissions Policy (For 2021-22)

Pele Trust Admissions Policy (for 2021-22) Admissions Procedure - How and when to apply The standard admission points for Pele Trust schools are entry to the primary phase in the Reception year and entry to the secondary phase in Year 7. These places are allocated for the start of the academic year in September. Northumberland residents should apply through Northumberland County Council’s admissions online portal; Newcastle residents should apply for places through Newcastle City Council’s admissions system. The deadline for secondary place applications is 31 October in the year prior to admission. For reception places the deadline for applications is 15 January in the year of admission. Applications received after these dates will be classed as late applications and will be processed after all of the applications received on time. Applications for places in other year groups, or after the start of the academic year, can be made at any time. These are referred to as in-year transfers. Primary schools also offer nursery places. Parents and carers should note that the allocation of Reception places does not take into account attendance at any specific nursery class or school. Children in the nursery class of the school will not be given priority nor are they guaranteed a Reception place in the main school. Admission of children outside their normal year group Parents may request that their child is admitted outside their normal age group if they feel their child is not ready to start school with their peers. Requests must be submitted in writing to the Headteacher of the school and include any supporting evidence from relevant professionals. -

Prospectus Secondary Physical Education Welcome to the NORTH EAST PARTNERSHIP SCITT

SECONDARY Best provider of postgraduate teacher training in the country (GTTG, 2015) Prospectus Secondary Physical Education Welcome to the NORTH EAST PARTNERSHIP SCITT The North East Partnership SCITT is a specialist physical education initial teacher training provider. We are the largest physical education provider in If you are thinking about becoming a teacher of the north east of England and one of the largest physical education you have definitely come to in the country. Our last three Ofsted judgements the right place. Last year 100% of our trainees have been outstanding and in 2013 we were passed the course, 100% were graded as good or graded outstanding in every category. We are outstanding and 100% have secured employment consistently ranked in the top ten in the Good in schools. Teacher Training Guide and in 2013 were identified as the top secondary SCITT in the country and in 2015 as the best provider in the country. Last year 100% of our trainees secured employment in schools. 2 | Secondary Prospectus Secondary Prospectus | 3 OUR VISION FOR EXCELLENCE The North East Partnership SCITT will create the next generation of outstanding physical education teachers who can inspire and motivate young people to foster a love for physical education and sport and thus achieve their full potential – in sport and in life. Highly effective partnerships and innovative teaching and learning are at the heart of all we do. 4 | Secondary Prospectus WHY TRAIN WITH US 1. We have consistently been graded as outstanding by Ofsted. 2. We are consistently identified as one of the top ten providers in the country in the Good Teacher Training Guide and in 2015 were identified as the best in the country. -

List of Not Outstanding Schools That Have Registered Only

List of Not Outstanding Schools that have registered only Name of School LA Name Bishop Douglass School Barnet Finchley Catholic High School Barnet Hasmonean High School Barnet JCoSS - Jewish Community Secondary School Barnet Monken Hadley CE Primary Barnet Osidge School Barnet Athersley South Primary Barnsley Beechen Cliff School Bath and North East Somerset Culverhay School Bath and North East Somerset Oakwood Park Grammar School Bath and North East Somerset Somervale School Bath and North East Somerset Church End Lower School Bedford Harrold Priory Middle School Bedford Margaret Beaufort Middle School Bedford Ursula Taylor Lower School Bedford Wootton Upper School & Arts College Bedford Bexleyheath School Bexley Chislehurst and Sidcup Grammar School Bexley Hurstmere Foundation School for Boys Bexley Lordswood Boys' School Bexley Peareswood Primary School Bexley St Catherine's Catholic School for Girls Bexley Welling School Bexley Acocks Green Primary School Birmingham Aston Manor Birmingham Jervoise School Birmingham Park View Business and Enterprise School Birmingham St. Paul's (Independent) School Birmingham St Wilfrid's C of E High School and Technology College. Blackburn with Darwen St Mary's Catholic College Blackpool Red Lane Primary School Bolton SS Simon and Jude CEPS Bolton St Paul's CEP Bolton Bournemouth School Bournemouth Chesterton Community College Bournemouth St Michael's CE (VC) Primary School Bournemouth The Bicknell School Bournemouth Coral College for Girls Bradford M A Institute Bradford Southmere Primary School -

PNV Jan 20 Issue

PONTELAND • MILBOURNE • MEDBURN • PRESTWICK • KIRKLEY ISSUE 172 | JAN 20 FREE monthly community magazine for Ponteland and district True blue as Conservatives hold Hexham constituency Special anniversary Planning go-ahead for new college partnership of school’s founding Snow patrols to counter winter weather woes is celebrated www.pontelandtowncouncil.co.uk pontnews&views 1 Thinking of retiring? Unsure of your options? Speak to a pensions expert For your free initial consultation give us a call on (01661) 821110 or email us at [email protected] CFS Independent Financial Advisers Limited, Lower Blyth Suite, Kirkley Hall, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE20 OAQ Belsay Woodland Burials Now Available JANUARY 2020 Lunch Special 2 courses for £8 3 courses for £10 2650 Happy hour pizza and pasta from £6 Monday - Friday 12pm - 7pm | Saturday 12pm - 6pm from 2899 Kids Eat for £1 All kid’s main courses £1 390 Add an ice cream cornet for 50p One child per paying adult. Monday - Friday 12pm - 6pm. Under 10s only. Available from 6th - 31st January 2020 Management reserve the right to withdraw or decline any offer at any time Enjoy 20% off your bill with this voucher! 20% Valid 06/01/2020 - 31/01/2020. Excludes Saturdays and Sundays and not valid in OFF conjunction with any other offers. Pont News & Views is published by Ponteland Town Council in conjunction with Ponteland Community Partnership. Inclusion of articles and advertising in Pont News & Views does not imply Ponteland Town Council’s or Ponteland Community Partnership’s endorsement, agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided. -

PNV Nov 19 Issue

PONTELAND • MILBOURNE • MEDBURN • PRESTWICK • KIRKLEY ISSUE 170 | NOV 19 FREE monthly community magazine for Ponteland and district Footballers score victory for playing fair Children strike Householders’ fury as development goes ahead gold as project Crackdown on motorists as retailer fits cameras reaches half way www.pontelandtowncouncil.co.uk pontnews&views 1 Belsay Woodland Burials Now Available 2650 from 2899 390 Thinking of retiring? Unsure of your options? Speak to a pensions expert BOOK NOW FOR CHRISTMAS OPEN EVERY DAY VIEW OUR WEBSITE FOR MORE INFORMATION For your free initial consultation www.fratelliponteland.co.uk give us a call on (01661) 821110 or email us at [email protected] CFS Independent Financial Advisers Limited, Lower Blyth Suite, Kirkley Hall, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE20 OAQ Pont News & Views is published by Ponteland Town Council in conjunction with Ponteland Community Partnership. Inclusion of articles and advertising in Pont News & Views does not imply Ponteland Town Council’s or Ponteland Community Partnership’s endorsement, agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided. If you would like to submit an article, feature or advertise contact: T. (0191) 5191306 E. [email protected] Westray, 16 Sunniside Lane, Cleadon Village, SR6 7XB. Produced by Cian creative pr Final bow as the team take on Brazil The Ponteland players who represented England Bella Russell flies the flag Fair play victory makes team the biggest winners Schoolgirl footballers from And in their final match, a seventh-eighth He added: “Even taking part in place play-off against a highly rated this tournament was an incredible Ponteland have proved Brazil, they lost 2-0. -

Middle, High & Secondary School Admissions 2018/2019

Middle, High & Secondary School Admissions 2018/2019 admissions.northumberland.gov.uk TIMETABLE OF DATES 11 September 2017: E-admissions portal opens. Information, Handbooks and application forms available on the Council’s website at: admissions.northumberland.gov.uk Paper forms available on request from: School Admissions Team, Wellbeing and Community Health Services Group, Northumberland County Council, County Hall, Morpeth, Northumberland NE61 2EF. 31 October 2017: Closing Date for Applications: E-admission portal closes at 12 midnight. Applications received after this date are considered late. 1 March 2018: Parents notified of the outcome of their applications for school places 15 March 2018: Last date for offers to be accepted by parents. DEADLINE FOR APPLICATIONS 31 October 2017 OFFERS DAY 1 March 2018 admissions.northumberland.gov.uk 2 Dear Parent / Carer Northumberland is an outstanding place to live. We also want to ensure that education in the County offers the best possible life chances for our young people. Your first application for a school place for your child is exciting but can also be confusing and worrying. The same can be said if your child is changing between schools at the end of a phase. Do we know everything there is to know? Have we made the right choice? The Council has written this Handbook as a guide and aid for these important decisions. The Handbook contains an explanation of the way schools in Northumberland are organised, the Schools’ Admission policies and how to apply for your preferred school(s). We include other information which will also be of use. The different school partnerships are explained as well as more general information.