Lew Puller's Fortunate Son and the Myth of Resolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Fortunate Marriage, OR, the Golden Glove. Tom Starboard. the Bold

X A i Ji Farmer’s^ <, m fortunate Marriage, O R, THE Golden Glove. Tom Starboard. : The Bold Hairy Capy / The Begg;‘P^ar Girl. ' ' Falkirk) Frinieo by j , Jobnstori' 1814. THE, GUI DEE CX OVi:. f A wealthy ypupip’S^u'yc uf Tanworth w'e hearj He counted a Nobiewan’s tisu^hcar moft fair, A d (or to marry her, n was his intern. All fuemls and rdaiipnshadg ven tbcirconfer::.. The time \va$ 'pnointed fer the wedding-day ; A young f.r jner vras choUn the father to be, Ai f on a^ the L.sdy the f rmer did (py, It i flmed her heart-—O mt heart flic did ay ! She turn’d from the’Squ re Sc nothing fhe faiJ, InUeafl-of being riiarned, fhr went to her bed. The thoughts of the farmer thf tun in her mind, -jPhe Vfay ter to have himilie (bon then did find. ■ , ■ ■ ' ’ Yt Coat, waiftcoa. 8s breeches, fhe then’did pu' on, And a-HunUngfli- v.’ent with her do; A irgiin She huntedail round where-flltefaru'ifei d d dwell, Be'caufe in her heart (he lov’d him fo.wtll. She oftec-times fi ecfl but nothing flie hiVi’d; At lerfgtiuhe yc urg farmer came in the field 'Then tor to djfcourie with him was her inter t; With herdogt: her g.yu for to meet him fhe went I thought you h d hren’aVi'.e wediii' g ftieayM 'fo ’wiirt on the f q iue. to give iann-nis nride. Ng, Su , fays the farmer, if the truth I may i’li.cu; give hsr «w»y, tor I love Iter orylel'. -

America's Changing Mirror: How Popular Music Reflects Public

AMERICA’S CHANGING MIRROR: HOW POPULAR MUSIC REFLECTS PUBLIC OPINION DURING WARTIME by Christina Tomlinson Campbell University Faculty Mentor Jaclyn Stanke Campbell University Entertainment is always a national asset. Invaluable in times of peace, it is indispensable in wartime. All those who are working in the entertainment industry are building and maintaining national morale both on the battlefront and on the home front. 1 Franklin D. Roosevelt, June 12, 1943 Whether or not we admit it, societies change in wartime. It is safe to say that after every war in America’s history, society undergoes large changes or embraces new mores, depending on the extent to which war has affected the nation. Some of the “smaller wars” in our history, like the Mexican-American War or the Spanish-American War, have left little traces of change that scarcely venture beyond some territorial adjustments and honorable mentions in our textbooks. Other wars have had profound effects in their aftermath or began as a result of a 1 Telegram to the National Conference of the Entertainment Industry for War Activities, quoted in John Bush Jones, The Songs that Fought the War: Popular Music and the Home Front, 1939-1945 (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2006), 31. catastrophic event: World War I, World War II, Vietnam, and the current wars in the Middle East. These major conflicts create changes in society that are experienced in the long term, whether expressed in new legislation, changed social customs, or new ways of thinking about government. While some of these large social shifts may be easy to spot, such as the GI Bill or the baby boom phenomenon in the 1940s and 1950s, it is also interesting to consider the changed ways of thinking in modern societies as a result of war and the degree to which information is filtered. -

![Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0418/download-music-for-free-in-work-even-though-it-gains-access-to-it-680418.webp)

Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It

Vol. 54 No. 3 NIEMAN REPORTS Fall 2000 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 4 Narrative Journalism 5 Narrative Journalism Comes of Age BY MARK KRAMER 9 Exploring Relationships Across Racial Lines BY GERALD BOYD 11 The False Dichotomy and Narrative Journalism BY ROY PETER CLARK 13 The Verdict Is in the 112th Paragraph BY THOMAS FRENCH 16 ‘Just Write What Happened.’ BY WILLIAM F. WOO 18 The State of Narrative Nonfiction Writing ROBERT VARE 20 Talking About Narrative Journalism A PANEL OF JOURNALISTS 23 ‘Narrative Writing Looked Easy.’ BY RICHARD READ 25 Narrative Journalism Goes Multimedia BY MARK BOWDEN 29 Weaving Storytelling Into Breaking News BY RICK BRAGG 31 The Perils of Lunch With Sharon Stone BY ANTHONY DECURTIS 33 Lulling Viewers Into a State of Complicity BY TED KOPPEL 34 Sticky Storytelling BY ROBERT KRULWICH 35 Has the Camera’s Eye Replaced the Writer’s Descriptive Hand? MICHAEL KELLY 37 Narrative Storytelling in a Drive-By Medium BY CAROLYN MUNGO 39 Combining Narrative With Analysis BY LAURA SESSIONS STEPP 42 Literary Nonfiction Constructs a Narrative Foundation BY MADELEINE BLAIS 43 Me and the System: The Personal Essay and Health Policy BY FITZHUGH MULLAN 45 Photojournalism 46 Photographs BY JAMES NACHTWEY 48 The Unbearable Weight of Witness BY MICHELE MCDONALD 49 Photographers Can’t Hide Behind Their Cameras BY STEVE NORTHUP 51 Do Images of War Need Justification? BY PHILIP CAPUTO Cover photo: A Muslim man begs for his life as he is taken prisoner by Arkan’s Tigers during the first battle for Bosnia in March 1992. -

The Oxford Democrat

Γ -Λ* '····■' — The Oxford Democrat. NUMBER II VOLUME 81. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, MARCH 17, 1914. The Part* Town cerned. If the boy chooses to throw- ■ι ι n 111 h m ι m m π m ι verse and Ma Foedick the lady rep- KllT D. PARK, ι Never Spray Tree» In Bloom. Mectlag. il AMONG THE FAKMEKS. away a fortune and at the same time resented to him that she had no in- Professor Surface, state zoologist c f usual on town meeting day, the Auctioneer, take a serpent to his bosom, be is wel- that she had studied Licensed COLDS, Pennsylvania, recently sent tbe follow Democrat leaned two edition· last week come; bookkeep- PARIS. MAINE. in t > the come to do so." and served as a bookkeeper before oUTU "I71I1D TBI FLOW." ing to tbe Practical Farmer, reply —the β rat giving the «tory of pro- :!A DEVOTEDi ing HEADACHES, BILIOUSNESS nee at thi * was well born and well bred, m Term· M<xler»W- a question as to what to oeedioga of the Pari· town meeting op A Agatha ber marriage. She asked If she g time: at while tie Spell bat she was at the wrong end of a her husband's The to should be remedied at once. de the adjournment noon, I not be given place. JUNKS, They 6 E. P. on practical agricultural topic· "I note witb interest that yon mak aecond the fall For of in her — Correspondence In gave proceeding». period prosperity family. WIFE fact that she bai been left bilitate the fo Addre·» all j^. -

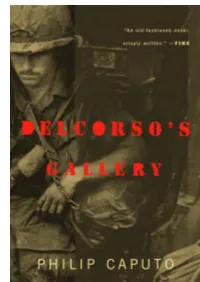

Download Delcorso's Gallery, Philip Caputo, Random House LLC, 2012

DelCorso's Gallery, Philip Caputo, Random House LLC, 2012, 0307822052, 9780307822055, 368 pages. A classic novel of Vietnam and its aftermath from Philip Caputo, whose Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir A Rumor of War is widely considered among the best ever written about the experience of war.At thirty-three, Nick DelCorso is an award-winning war photographer who has seen action and dodged bullets all over the world–most notably in Vietnam, where he served as an Army photographer and recorded combat scenes whose horrors have not yet faded in his memory. When he is called back to Vietnam on assignment during a North Vietnamese attempt to take Saigon, he is faced with a defining choice: should he honor the commitment he has made to his wife not to place himself in any more danger for the sake of his career, or follow his ambition back to the war-torn land that still haunts his dreams? What follows is a riveting story of war on two fronts, Saigon and Beirut, that will test DelCorso’s faith not only in himself, but in the nobler instincts of men.. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1j0zXiV Acts of Faith , Philip Caputo, May 3, 2005, Fiction, 669 pages. Philip Caputo’s tragic and epically ambitious new novel is set in Sudan, where war is a permanent condition. Into this desolate theater come aid workers, missionaries, and .... Dispatches , Michael Herr, 2009, History, 247 pages. Written on the front lines in Vietnam, "Dispatches" became an immediate classic of war reportage when it was published in 1977. -

AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 Songs, 2.8 Days, 5.36 GB

Page 1 of 28 **AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 songs, 2.8 days, 5.36 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I Am Loved 3:27 The Golden Rule Above the Golden State 2 Highway to Hell TUNED 3:32 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 3 Dirty Deeds Tuned 4:16 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 4 TNT Tuned 3:39 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 5 Back in Black 4:20 Back in Black AC/DC 6 Back in Black Too Slow 6:40 Back in Black AC/DC 7 Hells Bells 5:16 Back in Black AC/DC 8 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:16 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC 9 It's A Long Way To The Top ( If You… 5:15 High Voltage AC/DC 10 Who Made Who 3:27 Who Made Who AC/DC 11 You Shook Me All Night Long 3:32 AC/DC 12 Thunderstruck 4:52 AC/DC 13 TNT 3:38 AC/DC 14 Highway To Hell 3:30 AC/DC 15 For Those About To Rock (We Sal… 5:46 AC/DC 16 Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution 4:13 AC/DC 17 Blow Me Away in D 3:27 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 18 F.S.O.S. in D 2:41 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 19 Here Comes The Sun Tuned and… 4:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 20 Liar in E 3:12 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 21 LifeInTheFastLaneTuned 4:45 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 22 Love Like Winter E 2:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 23 Make Damn Sure in E 3:34 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 24 No More Sorrow in D 3:44 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 25 No Reason in E 3:07 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 26 The River in E 3:18 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 27 Dream On 4:27 Aerosmith's Greatest Hits Aerosmith 28 Sweet Emotion -

War on Film: Military History Education Video Tapes, Motion Pictures, and Related Audiovisual Aids

War on Film: Military History Education Video Tapes, Motion Pictures, and Related Audiovisual Aids Compiled by Major Frederick A. Eiserman U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 66027-6900 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Eiserman, Frederick A., 1949- War on film. (Historical bibliography ; no. 6) Includes index. 1. United States-History, Military-Study and teaching-Audio-visual aids-Catalogs. 2. Military history, Modern-Study and teaching-Audio- visual aids-Catalogs. I. Title. II. Series. E18I.E57 1987 904’.7 86-33376 CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................. vii Chapter One. Introduction ............................... 1 1. Purpose and Scope .................................. 1 2. Warnings and Restrictions .......................... 1 3. Organization of This Bibliography .................. 1 4. Tips for the Instructor ............................... 2 5. How to Order ........................................ 3 6. Army Film Codes ................................... 3 7. Distributor Codes .................................... 3 8. Submission of Comments ............................ 5 Chapter Two. General Military History ................. 7 1. General .............................................. 7 2. Series ................................................ 16 a. The Air Force Story ............................. 16 b. Air Power ....................................... 20 c. Army in Action ................................. 21 d. Between the Wars .............................. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

Jessica Rees [email protected] 760-834-8599

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Jessica Rees [email protected] 760-834-8599 FREE FAMILY ENTERTAINMENT EVERY FRIDAY AT TORTOISE ROCK CASINO’S LIVE AT THE ROCK CONCERT SERIES August Lineup Announced! TWENTYNINE PALMS, CA – (July 27, 2016) – Tortoise Rock Casino is proud present the ultimate in free family entertainment at Live at the Rock, featuring an exciting concert every Friday night in August for all ages 6+! The FREE Friday Concert Series features electrifying tribute bands and artists, performing on the outdoor stage at Tortoise Rock Casino. The concerts take place at 8 p.m. on Friday nights now through October. Before enjoying the concert at Live at the Rock, start off the night with a delicious bite to eat at Oasis Grille or enjoy a cocktail at Shelly’s Lounge. Free soda and soft drinks are also available! Live at the Rock is presented by Z107.7 FM. Listen to Z107.7 FM for updates and announcements about the Live at the Rock series. August kicks off with Heart Attack and a tribute to Heart on August 5. Their spot-on recreation of Heart’s music takes guests on a journey from their classic songs of the ‘70s to their chart-topping hits of the ‘80s, from “Barracuda” and “Crazy On You” to “These Dreams” and “Alone.” Experience the music of The Ramones on August 12 with The Rockaways. The band pays tribute to the legendary punk rockers and recreates such hits as “I Wanna Be Sedated,” “Glad To See You Go,” “Rockaway Beach” and many more. Grunge rock will be in the house when Nirvanish brings the music of Nirvana to Live at the Rock on August 19. -

The Influence of the Folk Music Revival on the Antiwar Movement During the Vietnam Era

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 12-19-2019 A Different Master of War: The Influence of the olkF Music Revival on the Antiwar Movement during the Vietnam Era Isabelle Gillibrand Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons A Different Master of War: The Influence of the Folk Music Revival on the Antiwar Movement during the Vietnam Era Isabelle Gillibrand Salve Regina University Department of History Senior Thesis Dr. Neary December 6, 2019 The author would like to express gratitude to Salve Regina University’s Department of History for financial support made possible through the John E. McGinty Fund in History. McGinty Funds provided resources to travel to Memphis and Nashville, Tennessee in the spring of 2019 to conduct primary research for the project. “What did you hear, my blue-eyed son? What did you hear, my darling young one?” -Bob Dylan, “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall,” 1963 In the midst of victorious rhetoric from the government, disturbing insight from the news media, and chaos from the protests, people heard the music of the Vietnam War era. The 1960s was known as a time of change, ranging from revised social norms to changing political stances to new popular music. Everyone seemed to have something to say about the war, musicians being no exception. The folk revival in the 1960s introduced young listeners to a different sound, one of rebellion and critical thought about their country. -

Megan A. Costello Announces the Sale of Her Chocolate Factory to Explore Flavorful New Pursuits

June 17, 2021 Contact: Kerry Grant Geyser [email protected] Phone: 702.723.9274 CHIEF CHOCOLATE OFFICER, STEWARD OF WILLIAMS SONOMA’S PEPPERMINT BARK FOR 19 YEARS, PIVOTS TO NEW ADVENTURES IN CANDY LAND AND BEYOND Megan A. Costello announces the sale of her chocolate factory to explore flavorful new pursuits San Francisco, CA – Megan A. Costello, founder, and former co-owner and Chief Chocolate Officer (CCO) at Easton Malloy, Inc., makers of the world famous Williams Sonoma Original Peppermint Bark, announces her new endeavor. After designing and building their newest chocolate and confection manufacturing facility in 2019, Megan is now setting a new trajectory for her life with food, chocolate and her namesake Megan A. Costello brand. “I am an entrepreneur at heart so, for me, the thrill is in envisioning a company, designing equipment, building factories and creating products and flavor profiles. To be a creator one has to be free to create and leave behind the day-to-day duties.” The new Megan A. Costello brand offers her expertise in product and flavor design, and includes collaborations alongside established industry colleagues. “It was more than a sugar rush to build my first factory in San Francisco! The city had just taken a major hit from the first tech bubble bursting and there was plenty of space to grow. It was perfect timing for burgeoning food entrepreneurs bootstrapping businesses and, for those of us in food (especially chocolate), we helped each other. We didn’t have role models for some of what we were doing and making. We were not descendants from generations of chocolatiers, but we were passionate and determined.