Crisis in the Kindergarten Why Children Need to Play in School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Carolina Colleges and Universities Approved Birth-Through-Kindergarten Teacher Education and Licensure Programs

North Carolina Colleges and Universities Approved Birth-through-Kindergarten Teacher Education and Licensure Programs The Early Educator Support, Licensure and Professional Development (EESLPD) Unit under the Early Education Branch, Division of Child Development and Early Education, makes every effort to ensure that all contact information is current. Please send revisions to [email protected] , Manager of EESLPD Unit. Appalachian State University *#+ Barton College *# Campbell University *# Dr. Dionne Busio, Director Dr. Jackie Ennis, Dean Dr. Connie Chester, Coordinator Birth-Through-Kindergarten Program School of Education Teacher Education Program Department of Family Y Child Studies PO Box 5000 PO Box 546 151 College Street Wilson, NC 27893 Buies Creek, NC 27506 Boone, NC 28608 (252) 399-6434 (910) 893-1655 (828) 262-2019 (413) 265-5385 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Dr. Denise Brewer, Interim Chair Department of Family & Child Studies 151 College Street Boone, NC 28608 (P) (828) 262-3120 (F) (828) 265-8620 [email protected] Catawba College *# East Carolina University *# Elizabeth City State University *#+ Dr. Donna James, Coordinator Barbara Brehm, Coordinator Dr. Nicole Austin, Coordinator Birth-Kindergarten Education BS Birth through Kindergarten Teacher Education Birth-Kindergarten Education 2300 West Innes Street (252) 328-1322 1704 Weeksville Road Salisbury, NC 28144 [email protected] (preferred) Elizabeth City, NC 27909 (P) (704) 637-4772 (BK degree, Licensure Only, Lateral Entry, BK add-on) (252) 335-8761 (F) (704) 637-4744 [email protected] [email protected] Dr. Archana Hegde, Birth-Kindergarten Graduate Program (MAEd) 131 Rivers West Greenville, NC 27858-4353 Phone: (252) 328-5712 [email protected] (preferred) Elon University* Fayetteville State University *# Greensboro College *# Dr. -

2016 List of Colleges to Which Our High School Seniors Have Been Accepted

2016 List of Colleges to which our High School Seniors Have Been Accepted Bulkeley High School American International College Capital Community College Central CT State University College of New Rochelle Connecticut College Dean College Delaware State University Eastern CT State University Hofstra University Iona College Johnson & Wales University Keene State College Lincoln College of New England Long Island University Manchester Community College Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts Mercy College Pace University Pine Manor College Porter & Chester Trade School Quinnipiac University Rhode Island College Rivier College Sacred Heart University Southern CT State University Southern New Hampshire University SUNY Binghamton College SUNY Plattsburgh SUNY Potsdam SUNY Stony Brook Syracuse University Trinity College Tunxis Community College University of Bridgeport University of Connecticut University of New Haven University of Saint Joseph University of Valley Forge Wentworth Institute of Technology West Virginia State University West Virginia University Western New England University Capital Prep American International College Assumption Bay Path CCSU Clark Atlanta Curry Curry Collge Dean ECSU Fisher Fisher College Hofstra Hussin Johnson & Wales Lincoln College of NE Maryland Eastern Shore Mitchell Morehouse New England College Penn St Penn State Penn Tech Purdue Quinnipiac Rivier Univ SCSU Springfield Suffolk Syracuse UCONN UHART Umass-Amherst Univ of Bridgeport Univ of FL Univ of Maine Univ of New Hampshire Univ of New Haven Univ of Rhode Island Univ of St Joesph Univ of St Joseph Univ of Texas WCSU West VA State Univ Western New England Classical Magnet School American University Amherst College Anna Maria College Assumption College Becker College Bryant University Cedar Crest College Central CT. -

BS in Education

B.S. in Education Early Childhood/Special Education (ECSE) Elementary/Special Education (EESE) Additional Program Requirements 1. Students must first be admitted to Towson University. Please note that a GPA of 3.0 or higher is required for program admittance. The Early Childhood/Special Education and Elementary Education/Special Education programs at TUNE only accepts applicants during the fall semester. 2. After completing the TU application, please submit via email a one-page, double-spaced essay explaining your reasons for entering the Early Childhood/Special Education program or the Elementary/Special Education pro- gram. The writing sample must be submitted to Toni Guidi at [email protected]. Please remember that seats in the cohorts are limited. It is never too early to apply to the program! About the Programs Class sizes are small and cohort membership fosters collaboration and partnership since progression through the program is uniform. ECSE students are eligible for dual certification in Early Childhood e(Pr K - Grade 3) and Special Education (Birth - Grade 3). EESE students are eligible for dual certification Elin ementary (Grades 1-6) and Special Education (Grades -1 8). Internships are completed locally in Harford and Cecil County schools. Students are guaranteed a screening interview by Harford County Public Schools. Toni Guidi, Program Coordinator Toni Guidi is a Clinical Instructor in the Department of Education. As a faculty member she has taught various graduate and undergraduate courses in the areas of curriculum and methods, formal tests and measurements, and behavior management. As well, she supervises interns as they complete their capstone experience in Harford County Professional Development Schools. -

LILLY Resume 2019

a n n e l i l l y o n e - p e r s o n e x h i b i t i o n s 2019 Abstractus, Gallery Kayafas, Boston, MA. 2017 Seattle Art Fair, Sponder Gallery, Boca Raton, FL. To See, curated by John Guthrie, VERY, Boston, MA. Mortui Vivos Docent, Roxbury Latin School, Boston, MA. 2016 Situating Movement: Anne Lilly, New Work, Suffolk University Art Gallery, Boston, MA. To Wreathe, Lunder Art Center, Lesley University, Cambridge, MA. 2014 New Work, William Baczek Fine Art, Northampton, MA. 2013 Bleaching Field, Rice/Polak Gallery, Provincetown, MA. Time Tendril, Hunter Gallery, Saint George’s School, Middletown, RI. Temporal Tincture, Galerie Swanström, New York, NY. 2011 Nimbus, Nesto Gallery, Milton Academy, Milton, MA. Anne Lilly: Kinetic Sculpture, Simon Gallery, Morristown, NJ. 2010 Sleights, Rice/Polak Gallery, Provincetown, MA. 2008 Kinetic Sculpture by A. M. Lilly, Hammond Gallery, Fitchburg State College, Fitchburg, MA. Anne Lilly: Kinetic Sculpture, Tunnel Gallery, Pittsburgh, PA. 2007 Aristotle Series, Rice/Polak Gallery, Provincetown, MA. Silent Sonnets, Arden Gallery, Boston, MA. 2005 Laden-Light, Artists’ Foundation, Boston, MA. 2004 Viscosity, Artspace, New Haven, CT. 2003 Order & Change, Mariani Gallery, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, CO. s e l e c t e d g r o u p e x h i b i t i o n s 2020 After Spiritualism: Loss and Transcendence in Contemporary Art, curated by Lisa Crossma, Fitchburg Art Museum, Fitchburg, MA. 2019 Espace et Tension, curated by Domitille D’Orgeval, Galerie Denise René (Marais), Paris, France. The Moon: Eternal Pearl, Concord Center for the Visual Arts, Concord, MA. -

Parenting Teens

Parenting Teens Positive stories about teens rarely make it into the headlines. But, believe it or not, nine in 10 teens do not get into trouble. Do we hear about those in the news?! ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ hether children are toddlers or teens, on more a role of counselor. The warmth, Wpreparing for parenting challenges is affection, and positive communication of a tough! The difficulty with teens is that they counselor, however, must be balanced with are becoming much larger, much more the teen’s need to be independent and in verbal, and are able to fight battles more on charge. One researcher found that teens an adult level. They may experiment with seek information from friends on social risk taking, and the stakes are higher than at events, dating, joining clubs, and other any other developmental stage to this point. social life aspects while they turn to their Teens do not turn into teens overnight. parents for information on education, career There are three phases of adolescence that plans, and money matters. include the teen years: preadolescence (age During late adolescence, there are many 9 to 13), middle adolescence (age 14 to 16) decisions to be made. Teens are beginning and late adolescence (age 17 to 20). to disengage, and they often prepare to During preadolescence, children feel leave home about the same time their disorganized, and their growth is rapid and parents are reflecting on their own lives and uneven. They are not quite adolescents yet needs. At this time, authority with children because their sexual maturity has not fully is redefined and there is a gradual shift completed, and they are often referred to as toward economic and emotional indepen- tweens, meaning between the stages of dence. -

Kindergarten Teacher's Pedagogical Knowledge and Its Relationship with Teaching Experience

International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development Vol. 9 , No. 2, 2020, E-ISSN: 2226-6348 © 2020 HRMARS Kindergarten Teacher’s Pedagogical Knowledge and Its Relationship with Teaching Experience Norzalikah Buyong, Suziyani Mohamed, Noratiqah Mohd Satari, Kamariah Abu Bakar, Faridah Yunus To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARPED/v9-i2/7832 DOI:10.6007/IJARPED/v9-i2/7832 Received: 13 April 2020, Revised: 16 May 2020, Accepted: 19 June 2020 Published Online: 29 July 2020 In-Text Citation: (Buyong, et al., 2020) To Cite this Article: Buyong, N., Mohamed, S., Satari, N. M., Abu Bakar, K., & Yunus, F. (2020). Kindergarten Teacher’s Pedagogical Knowledge and Its Relationship with Teaching Experience. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education & Development. 9(2), 805-814. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 9(2) 2020, Pg. 805 - 814 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARPED JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics -

Member Colleges

SAGE Scholars, Inc. 21 South 12th St., 9th Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107 voice 215-564-9930 fax 215-564-9934 [email protected] Member Colleges Alabama Illinois Kentucky (continued) Missouri (continued) Birmingham Southern College Benedictine University Georgetown College Lindenwood University Faulkner Univeristy Bradley University Lindsey Wilson College Missouri Baptist University Huntingdon College Concordia University Chicago University of the Cumberlands Missouri Valley College Spring Hill College DePaul University Louisiana William Jewell College Arizona Dominican University Loyola University New Orleans Montana Benedictine University at Mesa Elmhurst College Maine Carroll College Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Univ. Greenville College College of the Atlantic Rocky Mountain College Prescott College Illinois Institute of Technology Thomas College Nebraska Arkansas Judson University Unity College Creighton University Harding University Lake Forest College Maryland Hastings College John Brown University Lewis University Hood College Midland Lutheran College Lyon College Lincoln College Lancaster Bible College (Lanham) Nebraska Wesleyan University Ouachita Baptist University McKendree University Maryland Institute College of Art York College University of the Ozarks Millikin University Mount St. Mary’s University Nevada North Central College California Massachusetts Sierra Nevada College Olivet Nazarene University Alliant International University Anna Maria College New Hampshire Quincy University California College of the Arts Clark University -

Basics of University Pedagogy Learning Diary

Basics of University Pedagogy learning diary Lam Huynh March 2019 1 Becoming a teacher From the first seminar, I learned about the purpose of this course are 1) pro- viding a guideline to become a better teacher and 2) our University of Oulu expected lecturers to have at least 25 credits on teaching curriculum. To myself, I want to become a teacher who has the ability to pass the knowl- edge to students as well as encourage critical thinking among my students. I also want to help students prepare the necessary skills for their working life. I would like to learn how to create an active learning environment, in which students can learn by discovering the knowledge by themselves. One of the main job for teachers is student assessment. The grading of students should reflect their learning outcome as a way to ensure the actual learning process. However, I surprised that the university refers to the high passing rate, due to the fact that the sooner students get their degree, the better the university gains. During the class, there is a discussion about certain people with \teacher genes" and that extrovert are better suit to become teachers than introvert. I disagreed with this fixed-mindset argument because I think a good teacher is the one who provides and encourages students to learn [3]. As a first-year doctoral student, in this Spring semester, I had a lecture by myself. The lecture content is good, but I feel extremely nervous, then I end up rushing through the lecture. After that, I think I can do better. -

Northwestern Oklahoma State University Early Childhood Education Program General Education 63 Hours Includes Program Specific Gen

Northwestern Oklahoma State University Early Childhood Education Program General Education 63 Hours Includes Program Specific Gen. Educ. And the Oklahoma 4X12 Gen. Educ. Requirements for certification. Major Coursework 60 Hours Hrs. Hrs. Orientation 1 Early Childhood Education 31 ____ UNIV 1011 Ranger Connection ____ EDUC 3013 EC Family & Community Relations ____ EDUC 3043 Found. of Math Methods (PK-3) Communication and Symbols 24 ____ EDUC 3313 Children’s Literature ____ EDUC 3413 Emergent Literacy (K-3) ____ ENGL1113 Composition I (Prerequisite for EDUC 4413) ____ ENGL 1213 Composition II ____ EDUC 3523 EC Development & Learning ____ SCOM 1113 Intro to Speech Comm. * ____ EDUC 4203 Elementary Creative Activities ____ ENGL 4173 English Usage * ____ EDUC 4413 Diag/Corr Reading Problems ____ MATH 1403 Contemporary Math or * ____ EDUC 4503 EC Curriculum Implementation MATH 1513 College Algebra * ____ EDUC 4532 EC Assessment ____ MATH 2233 Struct. Con. I Arithmetic * ____ EDUC 4543 EC Science and S.S. Methods ____ MATH 2433 Struct. Con. II Math * ____ EDUC 4582 EC Apprenticeship ____ MATH 2633 Geometry for Elem. Teachers Professional Education 15 Social and Political Economic Systems 12 (minimum grade of “C” in 3000-4000 level courses.) ____ FIN 1113 Personal Finance ____ EDUC 2010 Educational Seminar ____ HIST 1483 U.S. History to 1877 or ____ EDUC 2013 Child/Adolescent Psychology HIST 1493 U.S. History since 1877 (Prerequisite for EDUC 3322) ____ GEOG 1113 Fundamentals of Geography ____ EDUC 2103 Foundations of Education ____ POLS 1113 -

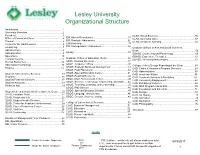

Lesley University Organizational Structure

Lesley University Organizational Structure Introduction ...1 University Overview .2 President 3 CLAS, Social Sciences .. ..56 EM, Alumni Recruitment .31 Office of Communications ...4 CLAS, Internship Office . .. 57 EM, Graduate Admissions . 32 Provost . ..5 CLAS, Academic Advising ... ...58 Center for the Adult Learner ...6 EM,Marketing . .. .. 33 EM, Undergraduate Admissions ..............34 e-Learning .....7 Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences, Advancement ....8 Dean. ..59 Library .. .....35 Administration ...9 GSASS, Counseling and Psychology . ...60 Operations ...10 GSASS, Expressive Therapies ...61 Graduate School of Education, Dean ... ...36 Campus Service .11 GSASS, Interdisciplinary Inquiry . .. .62 Human Resources ... ..12 GSOE, Division Directors ..........37 GSOE, Academic Affairs ... .38 Information Technology .. ... ...13 College of Art & Design Reporting to the Dean . ..63 GSOE, Strategic Business Development . ...39 Finance 14 CAD, Chairs & Academic Program Directors. ....64 GSOE, Field Placement .. ...40 CAD, Administration ..... ..65 GSOE, Special Education Center.. ... ...41 Student Administrative Services .. 15 CAD, Academic Affairs 66 GSOE, Reading Recovery .. ...42 Registrar ... 16 CAD, Academic Advising & Mentoring . 67 GSOE, Math Achievement Center . ...43 Student Financial Services 17 CAD, Community Engagement.... ................68 GSOE, Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math..... 44 Student Accounts.. .18 CAD, Exhibitions/Galleries.. .................69 GSOE, Teaching, Learning, and Leadership . .....45 -

Students' Perceptions of University Education

Research in Higher Education Journal Students’ perceptions of university education – USA vs. China Hongjiang Xu Butler University ABSTRACT As we continue in the global, competitive business environment, issues of globalization of education should not be overlooked. With study abroad programs for students and the internationalization of faculty, perceptions of students toward higher educational, particularly aspects of teaching and learning, from various cultural backgrounds will strongly influence educational systems. This research presents a comparative study, US versus China , of students’ perceptions toward higher education. Keywords: University education, student’s perceptions, higher education, educational orientation Student perceptions, Page 1 Research in Higher Education Journal INTRODUCTION Students from different education and culture background may have different perceptions towards higher education—particularly expectations related to teaching and learning. Students’ approach and orientation to education may further affect their academic decisions, expectations, and performance. Studies based on psychometric analysis and interviews have shown that there are two generalized types of educational orientation among students: a learning-oriented type and a grade-oriented type (Alexitch & Page, 1996; Katchadurian & Boli, 1985). The former focus primarily on values such as harmony, personal growth, the process of learning and intellectual competence, and this type of student espouses intrinsic values. The grade-oriented student primarily -

ALE Process Guide (Final)

Alternative Education Process Guide Division of Elementary and Secondary Education, Alternative Education Unit March 2021 Alternative Education Unit Contact Information Jared Hogue, Director of Alternative Education Arkansas Department of Education Division of Learning Services 1401 West Capitol Avenue, Suite 425 Little Rock, AR 72201 Phone: 501-324-9660 Fax: 501-375-6488 [email protected] C.W. Gardenhire, Ed.D., Program Advisor Arkansas Department of Education Division of Learning Services ASU-Beebe England Center, Room 106 P.O. Box 1000 Beebe, AR 72012 Phone: 501-580-5660 Fax: 501-375-6488 [email protected] Deborah Bales Baysinger, Program Advisor Arkansas Department of Education Division of Learning Services P.O. Box 250 104 School Street Melbourne, AR 72556 Phone: 501-580-2775 Fax: 501-375-6488 [email protected] 2 Introduction The purpose of this document is to supplement the Arkansas Department of Education - Division of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) Rules Governing Distribution of Student Special Needs Funding and the Determination of Allowable Expenditures of Those Funds, specifically Section 4.00 Special Needs - Alternative Learning Environment (ALE). Individuals using this document will be guided through particular contexts in the alternative education process. Each context provides a list of sample forms that can be used to satisfy regulatory compliance, a walk-through of those forms, and an overview of the process. Resources are provided where appropriate. For more information, please contact the Division of Elementary and Secondary Education, Alternative Education Unit. Throughout the document, green text boxes containing guidance will offer information and requirements for ALE programming.