Frank Bowling at Tate Britain: 'The Effect Is, Frankly, Emotional'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First-Ever Exhibition of British Pop Art in London

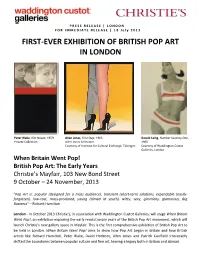

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 1 8 J u l y 2 0 1 3 FIRST- EVER EXHIBITION OF BRITISH POP ART IN LONDON Peter Blake, Kim Novak, 1959 Allen Jones, First Step, 1966 Gerald Laing, Number Seventy-One, Private Collection Allen Jones Collection 1965 Courtesy of Institute for Cultural Exchange, Tübingen Courtesy of Waddington Custot Galleries, London When Britain Went Pop! British Pop Art: The Early Years Christie’s Mayfair, 103 New Bond Street 9 October – 24 November, 2013 "Pop Art is: popular (designed for a mass audience), transient (short-term solution), expendable (easily- forgotten), low-cost, mass-produced, young (aimed at youth), witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, Big Business" – Richard Hamilton London - In October 2013 Christie’s, in association with Waddington Custot Galleries, will stage When Britain Went Pop!, an exhibition exploring the early revolutionary years of the British Pop Art movement, which will launch Christie's new gallery space in Mayfair. This is the first comprehensive exhibition of British Pop Art to be held in London. When Britain Went Pop! aims to show how Pop Art began in Britain and how British artists like Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake, David Hockney, Allen Jones and Patrick Caulfield irrevocably shifted the boundaries between popular culture and fine art, leaving a legacy both in Britain and abroad. British Pop Art was last explored in depth in the UK in 1991 as part of the Royal Academy’s survey exhibition of International Pop Art. This exhibition seeks to bring a fresh engagement with an influential movement long celebrated by collectors and museums alike, but many of whose artists have been overlooked in recent years. -

Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 12th, 1:30 PM - 2:45 PM Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Shelby Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Miller, Shelby, "Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art" (2017). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 1. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2016/004/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Shelby Miller Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Bibliographic Style: MLA 1 How does one define the concepts of space and place and further translate those theories to the Caribbean region? Through abstract modes of representation, artists from these islands can shed light on these concepts in their work. Involute theories can be discussed in order to illuminate the larger Caribbean space and all of its components in abstract art. The trialectics of space theory deals with three important factors that include the physical, cognitive, and experienced space. All three of these aspects can be displayed in abstract artwork from this region. By analyzing this theory, one can understand why Caribbean artists reverted to the abstract style—as a means of resisting the cultural establishments of the West. To begin, it is important to differentiate the concepts of space and place from the other. -

R.B. Kitaj: Obsessions

PRESS RELEASE 2012 R.B. Kitaj: Obsessions The Art of Identity (21 Feb - 16 June 2013) Jewish Museum London Analyst for Our Time (23 Feb - 16 June 2013) Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, West Sussex A major retrospective exhibition of the work of R. B. R.B. Kitaj, Juan de la Cruz, 1967, Oil on canvas, Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo; If Not, Not, 1975, Oil and black chalk on canvas, Scottish Kitaj (1932-2007) - one of the most significant National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh © R.B. Kitaj Estate. painters of the post-war period – displayed concurrently in two major venues for its only UK showing. Later he enrolled at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford, and then, in 1959, he went to the Royal College of Art in This international touring show is the first major London, where he was a contemporary of artists such as retrospective exhibition in the UK since the artist’s Patrick Caulfield and David Hockney, the latter of whom controversial Tate show in the mid-1990s and the first remained his closest painter friend throughout his life. comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s oeuvre since his death in 2007. Comprised of more than 70 works, R.B. During the 1960s Kitaj, together with his friends Francis Kitaj: Obsessions comes to the UK from the Jewish Museum Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Lucian Freud were Berlin and will be shown concurrently at Pallant House instrumental in pioneering a new, figurative art which defied Gallery, Chichester and the Jewish Museum London. the trend in abstraction and conceptualism. -

New Self-Portrait by Howard Hodgkin Takes Centre Stage in National Portrait Gallery Exhibition

News Release Wednesday 22 March 2017 NEW SELF-PORTRAIT BY HOWARD HODGKIN TAKES CENTRE STAGE IN NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY EXHIBITION Howard Hodgkin: Absent Friends, 23 March – 18 June 2017 National Portrait Gallery, London Portrait of the Artist Listening to Music by Howard Hodgkin, 2011-2016, Courtesy Gagosian © Howard Hodgkin; Portrait of the artist by Miriam Perez. Courtesy Gagosian. A recently completed self-portrait by the late Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017) will go on public display for the first time in a major new exhibition, Howard Hodgkin: Absent Friends, at the National Portrait Gallery, London. Portrait of the Artist Listening to Music was completed by Hodgkin in late 2016 with the National Portrait Gallery exhibition in mind. The large oil on wood painting, (1860mm x 2630mm) is Hodgkin’s last major painting, and evokes a deeply personal situation in which the act of remembering is memorialised in paint. While Hodgkin worked on it, recordings of two pieces of music were played continuously: ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’ composed by Jerome Kern and published in 1940, and the zither music from the 1949 film The Third Man, composed and performed by Anton Karas. Both pieces were favourites of the artist and closely linked with earlier times in his life that the experience of listening recalled. Kern’s song is itself a meditation on looking back and reliving the past. Also exhibited for the first time are early drawings from Hodgkin’s private collection, made while he was studying at Bath Academy of Art, Corsham in the 1950s. While very few works survive from this formative period in Hodgkin’s career, the drawings of a fellow student, Blondie, his landlady Miss Spackman and Two Women at a Table, exemplify key characteristics of Hodgkin’s approach which continued throughout his career. -

Frank Bowling Cv

FRANK BOWLING CV Born 1934, Bartica, Essequibo, British Guiana Lives and works in London, UK EDUCATION 1959-1962 Royal College of Art, London, UK 1960 (Autumn term) Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK 1958-1959 (1 term) City and Guilds, London, UK 1957 (1-2 terms) Regent Street Polytechnic, Chelsea School of Art, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1962 Image in Revolt, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1963 Frank Bowling, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1966 Frank Bowling, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1971 Frank Bowling, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, USA 1973 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1973-1974 Frank Bowling, Center for Inter-American Relations, New York, New York, USA 1974 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1975 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1976 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Watson/de Nagy and Co, Houston, Texas, USA 1977 Frank Bowling: Selected Paintings 1967-77, Acme Gallery, London, UK Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1979 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1980 Frank Bowling, New Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1981 Frank Bowling Shilderijn, Vecu, Antwerp, Belgium 1982 Frank Bowling: Current Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, -

Julian.Opie.Bio 2016 New.Pdf

2012 Sakshi Gallery, Mumbai, India Lisson Gallery, London, UK 2011 Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy National Portrait Gallery, London, UK Krobath, Berlin, Germany Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK (exh cat) Bob van Orsouw, Zurich, Switzerland 2010 Barbara Krakow Gallery, Boston, USA Mario Sequeira, Braga, Portugal IVAM, Valencia, Spain Galerist, Istanbul, Turkey 2009 Valentina Bonomo, Rome, Italy "Dancing in Kivik", Kivik Art Centre, Osterlen, Sweden Kukje Gallery, Seoul, South Korea (exh cat) Sakshi Gallery, Mumbai, India SCAI the Bathhouse, Tokyo, Japan Patrick de Brock, Knokke, Belgium 2008 MAK, Vienna, Austria (exh cat) Lisson Gallery, London, UK (exh cat) Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK (exh cat) Krobath Wimmer, Vienna, Austria Art Tower Mito, Japan (exh cat) 2007 Barbara Thumm, Berlin, Germany Museum Kampa, Prague, Czech Republic (exh cat) Barbara Krakow Gallery, Boston, USA King's Lynn art centre, Norfolk, UK 2006 CAC, Malaga, Spain (exh cat) Bob van Orsouw, Zurich, Switzerland Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK 2005 Mario Sequeira, Braga, Portugal La Chocolateria, Santiago de Compostela, Spain SCAI the Bathhouse, Tokyo, Japan MGM, Oslo, Norway Valentina Bonomo, Rome, Italy 2004 - 2005 Public Art Fund, City Hall Park, New York City, USA 2004 Lisson Gallery, London, UK (exh cat) Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden (exh cat) Kunsthandlung H. Krobath & B. Wimmer, Vienna, Austria Patrick de Brock Gallery, Knokke, Belgium Barbara Thumm Galerie, Berlin Krobath Wimmer, Wien, Austria 2003 Neues Museum, Staatliches Museum fur Kunst und Design -

Aspects of Modern British Art

Austin/Desmond Fine Art GILLIAN AYRES JOHN BANTING WILHELMINA BARNS-GRAHAM DAVID BLACKBURN SANDRA BLOW Aspects of DAVID BOMBERG REG BUTLER Modern ANTHONY CARO PATRICK CAULFIELD British Art PRUNELLA CLOUGH ALAN DAVIE FRANCIS DAVISON TERRY FROST NAUM GABO SAM HAILE RICHARD HAMILTON BARBARA HEPWORTH PATRICK HERON ANTHONY HILL ROGER HILTON IVON HITCHENS DAVID HOCKNEY ANISH KAPOOR PETER LANYON RICHARD LIN MARY MARTIN MARGARET MELLIS ALLAN MILNER HENRY MOORE MARLOW MOSS BEN NICHOLSON WINIFRED NICHOLSON JOHN PIPER MARY POTTER ALAN REYNOLDS BRIDGET RILEY WILLIAM SCOTT JACK SMITH HUMPHREY SPENDER BRYAN WYNTER DAVID BOMBERG (1890-1957) 1 Monastery of Mar Saba, Wadi Kelt, near Jericho, 1926 Coloured chalks Signed and dated lower right, Inscribed verso Monastery of Mar Saba, Wadi Kelt, near Jericho, 1926 by David Bomberg – Authenticated by Lillian Bomberg. 54.6 x 38.1cm Prov: The Artist’s estate Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London ‘David Bomberg once remarked when asked for a definition of painting that it is ‘A tone of day or night and the monument to a memorable hour. It is structure in textures of colour.’ His ‘monuments’, whether oil paintings, pen and wash drawings, or oil sketches on paper, have varied essentially between two kinds of structure. There is the structure built up of clearly defined, tightly bounded forms of the early geometrical-constructivist work; and there is, in contrast, the flowing, richly textured forms of his later period, so characteristic of Bomberg’s landscape painting. These distinctions seem to exist even in the palette: primary colours and heavily saturated hues in the early works, while the later paintings are more subtle, tonally conceived surfaces. -

Frank Bowling, Press Release 2017

FRANK BOWLING September 23, 2017 Marc Selwyn Fine Art is pleased to announce an exhibition of paintings by Frank Bowling, O.B.E., RA, opening September 23, 2017. Works in the exhibition range from the artist’s mid- 1970’s poured paintings to his recent canvases, which respond to American Abstract Expressionism with a wider diversity of technique and composition. Early pieces in the exhibition include prime examples of Bowling’s poured paintings in which the artist developed a unique mechanism to tilt the canvas, sending his acrylic medium flowing downward in spontaneous fusions of color. As Mel Gooding writes, “In their thrilling unpredictability, and their vertiginous disposition of the pure materials of their art, these poured paintings have about them something very close to the free-form excitement of contemporaneous advanced New York jazz, itself a brilliant manifestation of the modernist spirit.” Within a year, Bowling began to experiment again, producing more atmospheric works, recalling masters of the English landscape tradition such as Gainsborough and Turner. In Plunge, 1979 for example, clouds of sienna, aqua, muted yellow and pink are diffused in an ethereal composition made with pearl essence and chemical interventions. In more recent paintings, Bowling has added found objects, layers of canvas collage and experimental materials to his repertoire often using a highly personal sun drenched palette. In East Gate with Iona, 2013, horizontal bands of color recall Rothko’s compositions and become the background for a painterly flow of yellows and pinks. In Innerspace, 2012, thin veils of translucent color bring to mind the curtain-like washes of Morris Loius’s paintings of the 1960’s. -

Julian Opie CV

Julian Opie Lives and works in London, UK 1983 Goldsmiths College, London, UK 1958 Born in London, UK Selected Solo Exhibitions 2020 Berardo Museum, Lisbon, Portugal Galeria Duarte Sequeira, Braga, Portugal Lisson Gallery, Shanghai 2019 Eden Project, Cornwall, UK Lisson Gallery, New York, NY, USA Gerhardsen Gerner, Oslo, Norway Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg, Germany Galerie Krobath, Vienna, Austria 2018 National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia Krakow Witkin Gallery, Boston, USA Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK F1963, Busan, South Korea 2017 National Portrait Gallery, London, UK Suwon Ipark Museum of Art, Suwon, Korea Fosun Foundation, Shanghai, China Centro Cultural Bancaja, Valencia, Spain 2016 Galerie Krobath, Vienna, Austria Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin Germany Maho Kubota Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Art Geneve, Geneva, Switzerland 2015 Gerhardsen Gerner, Oslo, Norway ‘Recent Works’, Taidehalli Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Galeria Mário Sequeira, Braga, Portugal Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK Gerhardsen Gerner, Oslo, Norway “Winter”, British Council, New Delhi Galerie Bob van Orsouw, Zürich, Switzerland 2014 ‘Ikon Icon 2000s’, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK ‘Channing School for Girls’, ARK Gallery, London, UK SCAI The Bathhouse, Tokyo, Japan ‘Sculptures, Paintings and Film’, Mocak, Krakow, Poland ‘Julian Opie: Collected Works’, Bowes Museum, County Durham, UK; The Holburne Museum, Bath, UK Kukje Gallery, Seoul, South Korea Galerie Krobath, Berlin, Germany Gerhardsen Gerner Gallery, Berlin, Germany 2013 Valentina Bonomo Roma, Rome, Italy -

Sharjah Art Foundation Announces Autumn 2018 Exhibitions Featuring

For Immediate Release 12 September 2018 Frank Bowling, Australia to Africa, 1971. Acrylic on canvas, 280 x 712 cm. Hales Gallery London. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017 Sharjah Art Foundation Announces Autumn 2018 Exhibitions Featuring Solo Presentations by Frank Bowling, Amal Kenawy and Ala Younis, an Exhibition on Book Design in Japan, a Group Survey Featuring March Project 2018 Resident Artists, and a Tribute to 10 Years of the Foundation’s Production Programme Sharjah Art Foundation today announced its autumn 2018 exhibition programme, which features major solo exhibitions and group surveys highlighting influential artists from the region and around the world. In addition to solo exhibitions of the works of Frank Bowling, Amal Kenawy and Ala Younis, SAF will mount an exhibition of site-specific works created by the March Project 2018 resident artists and a tribute to the 10th anniversary of the Production Programme, which offers grants and professional support for the realisation of projects selected from an open call. This exhibition season will also inaugurate new institutional collaborations, including a three-year exchange with guest curator Yuko Hasegawa, Artistic Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, and a partnership with Haus der Kunst, Munich and the Museum of Modern Art Ireland (IMMA) for Frank Bowling: Mappa Mundi. SAF’s autumn 2018 roster continues the foundation’s commitment to building a bridge between local, regional, and international arts communities. ‘The autumn 2018 exhibition season offers a wide range of perspectives on contemporary art through the work of emerging and established artists from the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, and around the world, as well as that of artists who have created new projects with the support of our decade-long Production Programme,’ said Hoor Al Qasimi, Director of Sharjah Art Foundation. -

Mark Godfrey on Melvin Edwards and Frank Bowling in Dallas

May 1, 2015 Reciprocal Gestures: Mark Godfrey on Melvin Edwards and Frank Bowling in Dallas https://artforum.com/inprint/issue=201505&id=51557 Mark Godfrey, May 2015 View of “Frank Bowling: Map Paintings,” 2015, Dallas Museum of Art. From left: Texas Louise, 1971; Marcia H Travels, 1970. “THIS EXHIBITION is devoted to commitment,” wrote curator Robert Doty in the catalogue for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1971 survey “Contemporary Black Artists in America.” He continued, “It is devoted to concepts of self: self-awareness, self-understanding and self-pride— emerging attitudes which, defined by the idea ‘Black is beautiful,’ have profound implications in the struggle for the redress of social grievances.” In fact, the Whitney’s own commitment to presenting the work of African American artists might not have been as readily secured without the prompting of an activist organization, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition. The BECC had been founded in 1969 to protest the exclusion of painters and sculptors from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s documentary exhibition “Harlem on My Mind,” and that same year, several of its members had requested a meeting with the Whitney’s top brass, commencing a dialogue that was to go on for months. The back-and-forth was at times frustrating for the BECC’s representatives—artist Cliff Joseph, for example, was to recall that the Whitney leadership resisted the coalition’s request that a black curator organize the group exhibition. But unlike many art institutions at that time, the museum did recognize the strength of work by contemporary African American artists—and did bring that work to the public, not only in Doty’s survey but also, beginning in 1969, in a series of groundbreaking and prescient monographic shows. -

Patrick Caulfield (1936-2005)

Cristea Roberts Gallery Artist Biography 43 Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5JG +44 (0)20 7439 1866 [email protected] www.cristearoberts.com Patrick Caulfield (1936-2005) Patrick Caulfield studied at Chelsea School of Art and the Royal SELECTED PUBLIC COLLECTIONS College of Art between 1956-1963. He later taught at the Chelsea School of Art for eight years. Caulfield was awarded the Jerwood AUS Art Gallery of Western Australia Painting Price in 1995, and obtained an Order of the British National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Empire in 1996. He was also shortlisted for The Turner Prize in DE Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1987. His work is characterized by a reductive, streamlined use UK Government Art Collection London of line, and banal, everyday objects saturated in colour. Caulfield National Museum of Wales, Cardiff died in 2005, having made an indelible contribution to British Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, UK painting and printmaking. Tate Gallery, London Victoria and Albert Museum, London SELECTED EXHIBITIONS Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool USA Dallas Museum, Texas 2019 Patrick Caulfield: Morning, Night and Noon, Waddington Harry N Abrams Collection, New York Custot, London, UK Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 2014 Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Cumbria, UK 2013 Tate Britain, London, UK Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK 2010 No New Thing Under the Sun, Tennant Gallery, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK Group Exhibition, Waddington Galleries, London, UK 2009 Prints 1964 – 1999, Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK 2006 Special Summer