Understanding Visual Rhetoric in Digital Writing Environments Author(S): Mary E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Rhetoric: Toward an Integrated Theory

TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION QUARTERLY, 14(3), 319–325 Copyright © 2005, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Digital Rhetoric: Toward an Integrated Theory James P. Zappen Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute This article surveys the literature on digital rhetoric, which encompasses a wide range of issues, including novel strategies of self-expression and collaboration, the characteristics, affordances, and constraints of the new digital media, and the forma- tion of identities and communities in digital spaces. It notes the current disparate na- ture of the field and calls for an integrated theory of digital rhetoric that charts new di- rections for rhetorical studies in general and the rhetoric of science and technology in particular. Theconceptofadigitalrhetoricisatonceexcitingandtroublesome.Itisexcitingbe- causeitholdspromiseofopeningnewvistasofopportunityforrhetoricalstudiesand troublesome because it reveals the difficulties and the challenges of adapting a rhe- torical tradition more than 2,000 years old to the conditions and constraints of the new digital media. Explorations of this concept show how traditional rhetorical strategies function in digital spaces and suggest how these strategies are being reconceived and reconfiguredDo within Not these Copy spaces (Fogg; Gurak, Persuasion; Warnick; Welch). Studies of the new digital media explore their basic characteris- tics, affordances, and constraints (Fagerjord; Gurak, Cyberliteracy; Manovich), their opportunities for creating individual identities (Johnson-Eilola; Miller; Turkle), and their potential for building social communities (Arnold, Gibbs, and Wright; Blanchard; Matei and Ball-Rokeach; Quan-Haase and Wellman). Collec- tively, these studies suggest how traditional rhetoric might be extended and trans- formed into a comprehensive theory of digital rhetoric and how such a theory might contribute to the larger body of rhetorical theory and criticism and the rhetoric of sci- ence and technology in particular. -

Writing Systems Reading and Spelling

Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems LING 200: Introduction to the Study of Language Hadas Kotek February 2016 Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Outline 1 Writing systems 2 Reading and spelling Spelling How we read Slides credit: David Pesetsky, Richard Sproat, Janice Fon Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems What is writing? Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. –Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and speech Until the 1800s, writing, not spoken language, was what linguists studied. Speech was often ignored. However, writing is secondary to spoken language in at least 3 ways: Children naturally acquire language without being taught, independently of intelligence or education levels. µ Many people struggle to learn to read. All human groups ever encountered possess spoken language. All are equal; no language is more “sophisticated” or “expressive” than others. µ Many languages have no written form. Humans have probably been speaking for as long as there have been anatomically modern Homo Sapiens in the world. µ Writing is a much younger phenomenon. Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems (Possibly) Independent Inventions of Writing Sumeria: ca. 3,200 BC Egypt: ca. 3,200 BC Indus Valley: ca. 2,500 BC China: ca. 1,500 BC Central America: ca. 250 BC (Olmecs, Mayans, Zapotecs) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and pictures Let’s define the distinction between pictures and true writing. -

Writing Systems: Their Properties and Implications for Reading

Writing Systems: Their Properties and Implications for Reading Brett Kessler and Rebecca Treiman doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199324576.013.1 Draft of a chapter to appear in: The Oxford Handbook of Reading, ed. by Alexander Pollatsek and Rebecca Treiman. ISBN 9780199324576. Abstract An understanding of the nature of writing is an important foundation for studies of how people read and how they learn to read. This chapter discusses the characteristics of modern writing systems with a view toward providing that foundation. We consider both the appearance of writing systems and how they function. All writing represents the words of a language according to a set of rules. However, important properties of a language often go unrepresented in writing. Change and variation in the spoken language result in complex links to speech. Redundancies in language and writing mean that readers can often get by without taking in all of the visual information. These redundancies also mean that readers must often supplement the visual information that they do take in with knowledge about the language and about the world. Keywords: writing systems, script, alphabet, syllabary, logography, semasiography, glottography, underrepresentation, conservatism, graphotactics The goal of this chapter is to examine the characteristics of writing systems that are in use today and to consider the implications of these characteristics for how people read. As we will see, a broad understanding of writing systems and how they work can place some important constraints on our conceptualization of the nature of the reading process. It can also constrain our theories about how children learn to read and about how they should be taught to do so. -

Defining Visual Rhetorics §

DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § Edited by Charles A. Hill Marguerite Helmers University of Wisconsin Oshkosh LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS 2004 Mahwah, New Jersey London This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Copyright © 2004 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers 10 Industrial Avenue Mahwah, New Jersey 07430 Cover photograph by Richard LeFande; design by Anna Hill Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Definingvisual rhetorics / edited by Charles A. Hill, Marguerite Helmers. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8058-4402-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-8058-4403-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Visual communication. 2. Rhetoric. I. Hill, Charles A. II. Helmers, Marguerite H., 1961– . P93.5.D44 2003 302.23—dc21 2003049448 CIP ISBN 1-4106-0997-9 Master e-book ISBN To Anna, who inspires me every day. —C. A. H. To Emily and Caitlin, whose artistic perspective inspires and instructs. —M. H. H. Contents Preface ix Introduction 1 Marguerite Helmers and Charles A. Hill 1 The Psychology of Rhetorical Images 25 Charles A. Hill 2 The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments 41 J. Anthony Blair 3 Framing the Fine Arts Through Rhetoric 63 Marguerite Helmers 4 Visual Rhetoric in Pens of Steel and Inks of Silk: 87 Challenging the Great Visual/Verbal Divide Maureen Daly Goggin 5 Defining Film Rhetoric: The Case of Hitchcock’s Vertigo 111 David Blakesley 6 Political Candidates’ Convention Films:Finding the Perfect 135 Image—An Overview of Political Image Making J. -

Communication Models and the CMAPP Analysis

CHAPTER 2 Communication Models and the CMAPP Analysis f you want to find out the effect on Vancouver of a two-foot rise in sea level, you wouldn’t try to melt the polar ice cap and then visit ICanada. You’d try to find a computer model that would predict the likely consequences. Similarly, when we study technical communication, we use a model. Transactional Communication Models Various communication models have been developed over the years. Figure 2.1 on the next page shows a simple transactional model, so called to reflect the two-way nature of communication. The model, which in principle works for all types of oral and written communication, has the following characteristics: 1. The originator of the communication (the sender) conveys (trans- mits) it to someone else (the receiver). 2. The transmission vehicle might be face-to-face speech, correspon- dence, telephone, fax, or e-mail. 3. The receiver’s reaction (e.g., body language, verbal or written response)—the feedback—can have an effect on the sender, who may then modify any further communication accordingly. 16 Chapter 2 FIGURE 2.1 A Simple Transactional Model As an example, think of a face-to-face conversation with a friend. As sender, you mention what you think is a funny comment made by another student named Maria. (Note that the basic transmission vehicle here is the sound waves that carry your voice.) As you refer to her, you see your friend’s (the receiver’s) face begin to cloud over, and you remember that your friend and Maria strongly dislike each other. -

Learning to Write and Writing to Learn

Chapter 6 in: Hougen, M.C. (2013). Fundamentals of Literacy Instruction & Assessment: 6-12. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. In publication. Learning to Write and Writing to Learn By Joan Sedita Classroom Scenario In a middle school history class, the students are writing about several pieces of text that include a primary source, a textbook section, and a history magazine article. The writing assignment is to answer an extended response question by synthesizing information and using text evidence from the three sources. The teacher has given the students a set of guidelines that describes the purpose and type of the writing, the suggested length of the piece, and specific requirements such as how many main ideas should be included. The teacher has differentiated the assignment to meet the needs of students with a variety of writing skills. Scaffolds such as a pre-writing template have been provided for students who struggle with planning strategies. The teacher has provided models of good writing samples and has also provided opportunities for students to collaborate at various stages of the writing process. This is a classroom where the teacher is teaching students to write and also using writing to help them learn content. Unfortunately, classrooms like this are rare. Along with reading comprehension, writing skill is a predictor of academic achievement and essential for success in post-secondary education. Students need and use writing for many purposes (e.g., to communicate and share knowledge, to support comprehension and learning, to explore feelings and beliefs). Writing skill is also becoming a more necessary skill for success in a number of occupations. -

DOCUMENT RESUME Ruetz, Nancy Effective Communication. Improving

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 424 385 CE 077 295 AUTHOR Ruetz, Nancy TITLE Effective Communication. Improving Reading, Writing, Speaking, and Listening Skills in the Workplace. Instructor's Guide. Workplace Education. Project ALERT. INSTITUTION Wayne State Univ., Detroit, MI. Coll. of Education. SPONS AGENCY Office of Vocational and Adult Education (ED), Washington, DC. National Workplace Literacy Program. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 115p.; For other "Project ALERT" reports, see CE 077 287-302. CONTRACT V198A40082-95 AVAILABLE FROM Workplace Education: Project ALERT, Wayne State University, 373 College of Education, Detroit, MI 48202 ($40 plus $5 shipping). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; Basic Skills; Communication Skills; Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; *Listening Skills; *Reading Skills; *Speech Skills; Staff Development; Teaching Guides; Transfer of Training; *Workplace Literacy; *Writing Skills ABSTRACT This instructor's guide contains materials for a 30-hour course that focuses on reading, writing, speaking, and listening and targets ways to improve these skills on the job. The course description lists target audience, general objective, and typical results observed. The next section gives instructors basic information related to providing successful educational programs in a workplace setting, an instructor's lexicon of strategies and principles that can be used in teaching, instructor's role and responsibilities, and course objectives. An explanation of lesson format lists six parts of the template used to design the lessons--understanding/outcome, materials, demonstration, exercise/engagement, workplace application, and evaluation/comments. A sample template and explanation of each part follows. A section on planning and scheduling deals with time requirements, class size, expected outcomes, prerequisites, and suggested timing for each lesson. -

Writing Language

Writing language Linguists generally agree with the following statement by one of the founders of the modern science of language. Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Some version of this is clearly true, as we can see by looking at the history of the human species and of each human individual. In both regards, spoken language precedes written language. Speech Writing Present in every society Present only in some societies, and only rather recently Learned before writing Learned after speech is acquired Learned by all children in normal Learned only by instruction, and often not circumstances, without instruction learned at all Human evolution has made speaking Evolution has not specifically favored easier writing Another way to express Bloomfield's point is to say that writing is "parasitic" on speech, expressing some but not all of the things that speech expresses. Specifically, writing systems convey the sequence of known words or other elements of a language in a real or hypothetical utterance, and indicate (usually somewhat less well) the pronunciation of words not already known to the reader. Aspects of speech that writing leaves out can include emphasis, intonation, tone of voice, accent or dialect, and individual characteristics. Some caveats are in order. In the first place, writing is usually not used for "recording language" in the sense of transcribing speech. Writing may substitute for speech, as in a letter, or may deploy the expressive resources of spoken language in visual structures (such as tables) that can't easily be replicated in spoken form at all. -

Writing Linguistics Abstracts Maggie Tallerman

Writing linguistics abstracts Maggie Tallerman An abstract is a one- (or occasionally two-) page summary of a paper intended for presentation at an academic conference. The abstract is sent to the programme committee responsible for choosing papers to be presented at the conference. The committee evaluates your abstract alongside other submissions, and decides entirely on the basis of the abstract whether or not your paper should be accepted. Sometimes the committee will evaluate papers from all (or any) subfields covered by the conference; alternatively, your abstract may be sent out to a specialist in that particular subfield. The likelihood is that a number of abstracts submitted to any given conference will be rejected: for instance, the rejection rate for the two most general linguistics conferences in the UK and the USA (respectively the Linguistics Association of Great Britain and the Linguistic Society of America) is around 50%. Obviously, the rejection rate at a postgraduate conference may be lower, but this does not mean that all abstracts will be accepted. Abstracts are typically submitted anonymously, that is with a title but not the author’s name or institution, although a version including the author’s name may subsequently be printed in the book of abstracts for the meeting in question. The abstract is your first chance to promote your work to the linguistic public. It should be a short summary of a paper you are (or will soon be) prepared to give in public. The abstract is intended to cover both the main point(s) and conclusion(s) of the paper, and the arguments used to reach these conclusions. -

The Benefits of Writing M Cecil Smith, Ph.D

The Benefits of Writing M Cecil Smith, Ph.D. 1 1CISLL Co-Founder and Faculty Affiliate, Associate Dean for Research, College of Education & Human Services, West Virginia University It is likely that most adults do not give much thought to the writing that they do – in terms of the amount of text produced, quality of the written work, or the variety of writing tasks in which they engage. Typically, writing in everyday life tends to be performed for either the mundane tasks of personal and household management – shopping lists, phone messages, reminder notes to the kids – or for work-related tasks, such as inter-office memos, sales reports, and personnel evaluations (Brandt, 2001). Writing using a computer or smart phone is increasingly common with the spread of technology into all aspects of modern life, although there are generational and demographic differences in the practice of using a computer for writing. Cohen, White, and Cohen (2008), for example, found that younger, better educated, and employed US adults spent more time writing with computers, while older, less educated, and non-working persons spent more time writing using paper. While the variety of writing tasks adults engage in might be thought of as essential to work and home life, many everyday writing tasks probably contribute little to the overall quality of individuals’ intellectual and emotional lives. Of course, a significant number of adults engage in extensive and meaningful writing tasks. The most obvious examples are professional writers – journalists, book and short story authors, poets, and essayists, opinion columnists, college professors. The products of their work can be said to contribute to society in important ways: Inspiring and entertaining readers, reporting and analyzing significant political, cultural, and world events, critiquing government officials’ actions, educating children, youth, and adults. -

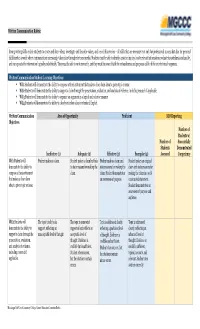

Written Communication Rubric Strong Writing Skills Enable Students To

Written Communication Rubric Strong writing skills enable students to create and share ideas, investigate and describe values, and record discoveries – all skills that are necessary not only for professional success but also for personal fulfillment in a world where communication increasingly takes place through electronic media. Students must be able to identify areas for inquiry, locate relevant information, evaluate its usefulness and quality, and incorporate the information logically and ethically. They must be able to write correctly, and they must be aware that different audiences and purposes call for different rhetorical responses. Written Communication Student Learning Objectives: WC1 Students will demonstrate the ability to compose a thesis statement that makes a clear claim about a given topic or issue. WC2 Students will demonstrate the ability to support a claim through the presentation, evaluation, and analysis of evidence, including research if applicable. WC3 Students will demonstrate the ability to organize an argument in a logical and cohesive manner. WC4 Students will demonstrate the ability to clearly articulate ideas in standard English. Written Communication Area of Opportunity Proficient SLO Reporting Objectives Number of Students w/ Number of Successfully Students Demonstrated Ineffective (1) Adequate (2) Effective (3) Exemplar (4) Assessed Competency WC1 Students will Student makes no claim. Student makes a claim but fails Student makes a claim and Student makes an original demonstrate the ability to to state reasons for making the states reasons for making the claim and states reasons for compose a thesis statement claim. claim. Student demonstrates making the claim in a well- that makes a clear claim an awareness of purpose. -

Naturalizing Peirce's Semiotics: Ecological Psychology's Solution To

Naturalizing Peirce’s Semiotics: Ecological Psychology’s Solution to the Problem of Creative Abduction Alex Kirlik and Peter Storkerson It is difficult not to notice a curious unrest in the philosophic atmo- sphere of the time, a loosening of old landmarks, a softening of oppo- sitions, a mutual borrowing from one another on the part of systems anciently closed, and an interest in new suggestions, however vague, as if the one thing sure were the inadequacy of extant school-solutions. The dissatisfactions with these seems due for the most part to a feeling that they are too abstract and academic. Life is confused and super- abundant, and what the younger generation appears to crave is more of the temperament of life in its philosophy, even though it were at some cost of logical rigor and formal purity. William James (1904) Abstract. The study of model-based reasoning (MBR) is one of the most interesting recent developments at the intersection of psychology and the phi- losophy of science. Although a broad and eclectic area of inquiry, one central axis by which MBR connects these disciplines is anchored at one end in the- ories of internal reasoning (in cognitive science), and at the other, in C.S. Peirce’s semiotics (in philosophy). In this paper, we attempt to show that Peirce’s semiotics actually has more natural affinity on the psychological side with ecological psychology, as originated by James J. Gibson and especially Egon Brunswik, than it does with non-interactionist approaches to cognitive science. In particular, we highlight the strong ties we believe to exist between the triarchic structure of semiotics as conceived by Peirce, and the similar triarchic stucture of Brunswik’s lens model of organismic achievement in irre- ducibly uncertain ecologies.