2 2014 Australia-New Zealand Study Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

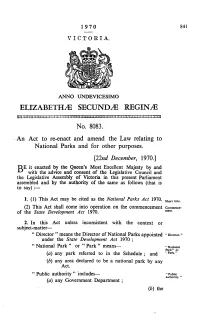

ELIZABETHS Secundy^ REGINS No. 8083. an Act to Re-Enact And

19 7 0 841 VICTORIA. ANNO UNDEVICESIMO ELIZABETHS SECUNDy^ REGINS No. 8083. An Act to re-enact and amend the Law relating to National Parks and for other purposes. [22nd December, 1970.] D E it enacted by the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty by and •*-' with the advice and consent of the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly of Victoria in this present Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows (that is to say) :— 1. (1) This Act may be cited as the National Parks Act 1970. short utie. (2) This Act shall come into operation on the commencement commence- of the State Development Act 1970. ""' 2. In this Act unless inconsistent with the context or subject-matter— " Director " means the Director of National Parks appointed "Director." under the State Development Act 1970 ; " National Park " or " Park " means— -National Park" or (a) any park referred to in the Schedule ; and "P"''" (b) any area declared to be a national park by any Act. "Public authority" includes— -Pubiic authority.'' (a) any Government Department ; (b) the 842 1970. National Parks. No. 8083 (Jb) the Victorian Railways Commissioners, State Rivers and Water Supply Commission, the Country Roads Board, the Forests Commission, the State Electricity Commission of Victoria, the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works, the Geelong Waterworks and Sewerage Trust, any waterworks trust or any local governing body within the meaning of the Water Act 1958, the council of any municipality and any other body of persons corporate or unincorporate declared by the Governor in Council to be a public authority for the purposes of this Act. -

Protecting Our Environment Inside This Issue

reFire Recoverygrow... a natural progression h A newsletter by Parks Victoria and the Department of Sustainability and Environment on public land fire recovery April 2010 Over 287,000 hectares of Victoria’s public land was burnt in the Inside this issue: February 2009 bushfires, including almost 100,000 hectares of national and state parks and reserves managed by Parks • Protecting our Environment Victoria and nearly 170,000 hectares of state forests and reserves • Connecting with Community managed by the Department of Sustainability and Environment • Honouring our History (DSE). The most severely affected parks were Kinglake National • Our Vital Volunteers Park, Wilsons Promontory National Park, Bunyip State Park, • A Dream of Discoveries Cathedral Range State Park and Yarra Ranges National Park. The fires devastated the Ash Forests through the Central Highlands. ... plus an update on fire-affected parks and reserves The fires impacted many visitor sites and forced the closure of many more parks and state forests. They also put at risk Protecting our Environment threatened plant and animal species, and affected indigenous The scale and intensity of the fires were a significant disruption to and post settlement heritage sites. But since that catastrophic ecosystems. Many animals – not all of them officially recognised day, Parks Victoria and the Department of Sustainability and as endangered – were put at risk and needed special attention. Environment (DSE) have been working closely with the Victorian Concern for species such as Helmeted Honeyeater, Brush-tailed Bushfire Reconstruction and Recovery Authority (VBRRA) Phascogale, Long-nosed Potoroos, Greater and Yellow-bellied to rebuild and reopen areas, and protect our natural and Gliders, Southern Brown Bandicoot and Broad Toothed Rat cultural values. -

Relazione Finale Del Progetto ANSFR : Proposte Per Il Miglioramento Della Valutazione E Della Gestione Del Rischio D'incendio in Europa

Relazione finale del Progetto ANSFR : proposte per il miglioramento della valutazione e della gestione del rischio d'incendio in Europa Report emesso da Northumberland Fire and Rescue Service (Regno Unito) Frederikssund-Halsnæs Fire and Rescue Department (Danimarca) Corpo Nazionale dei Vigili del Fuoco – Nucleo Investigativo Antincendi (Italia) Emergency Services College (Finlandia) Kanta-Häme Emergency Services (Finlandia) South West Finland Emergency Services (Finlandia) Il presente documento presenta le proposte del Progetto ANSFR t. Il Progetto ANSFR è stato cofinanziato dalla Direzione Generale per l'Ambiente della Commissione Europea e dal Civil Protection Financial Instrument 2008 Call for Proposals (numero convenzione finanziamento: 070401/2008/507848/SUB/A3). La Commissione Europea non è responsabile delle informazioni contenute nel presente documento e dell'uso che ne viene fatto. © La presente pubblicazione, a esclusione dei logo, può essere riprodotta gratuitamente in qualsiasi formato o mezzo destinato alla ricerca, analisi privata o per informazione interna tra le organizzazioni, a condizione che le informazioni contenute vengano riprodotte con precisione e non vengano utilizzate in contesti equivoci. Il titolo della pubblicazione deve essere menzionato e il Northumberland Fire and Rescue Service, il Frederikssund-Halsnæs Fire and Rescue Department, il Corpo Nazionale dei Vigili del Fuoco – Nucleo Investigativo Antincendi e l'Emergency Services College Finland devono essere riconosciuti quali proprietari del materiale contenuto -

National Parks Authority

1970 VICTORIA REPORT OF THE NATIONAL PARKS AUTHORITY FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30rH JUNE, 1968 Ordered by the Legislative Assembly to be printed, 15th September, 1970. By At~thority: C. H. RIXON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 22.-7938/70.-PRICB 40 cents. NATIONAL PARKS AUTHORITY TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30th JUNE, 1968 To the Honorable Sir Henry Bolte, K.C.M.G., M.L.A., Premier of Victoria, Melbourne, 3002. SIR, In accordance with the requirements of Section 15 of the National Parks Act 1958 (No. 6326), the Authority has the honour to submit to you for presentation to Parliament, its Twelfth Annual Report covering its activities for the year ended 30th June, 1968. THE AUTHORITY. The membership of the National Parks Authority during the year under review was as follows:- Chairman : The Honorable J. W. Manson, M.L.A., Minister of State Development. Deputy C~airman : J. H. Aldred, F.R.I.P.A. Members: A. J. Holt, Secretary for Lands ; A. 0. P. Lawrence, B.Sc. (Adel.), Dip. For. (Oxon.), Dip. For. (Canberra), Chairman, Forests Commission of Victoria; R. G. Downes, M.Agr.Sc., F.A.I.A.S., Chairman, Soil Conservation Authority; A. Dunbavin Butcher, M.Sc. (Melb.), Director of Fisheries and Wildlife; Dewar W. Goode, representing organizations concerned with the protection of native fauna and flora ; G. M. Pizzey, representing persons having a special interest in national parks ; E. H. R. Burt, representing the Victorian Ski Association ; G. E. Hindle, representing the Victorian Government Tourist Bureau ; L. H. Smith, M.Sc., D.Phil. -

Application of Fire Behaviour to Fire Danger and Wildfire Threat Modelling in New Zealand

Application of Fire Behaviour to Fire Danger and Wildfire Threat Modelling in New Zealand H.G. Pearce1, K. Majorhazi2 1 New Zealand Forest Research Institute, Christchurch, New Zealand 2 New Zealand Fire Service, Wellington, New Zealand Abstract Information on fire behaviour in different vegetation types is an essential input in wildland fire management system applications. This paper describes how fire behaviour models derived from experimental burning and wildfire documentation have been used as the basis for developing a number of fire management decision support tools in New Zealand. Three separate spatial applications have been produced for modelling current, historical and forecasted fire dangers using the Fire Weather Index and Fire Behaviour Prediction components of the New Zealand Fire Danger Rating System. Historical peak summer fire climate components were defined for use in the New Zealand Wildfire Threat Analysis model within both the Hazard component (Head Fire Intensity) and the Risk component to model the probability of sustained ignition. This information is useful for long-term strategic fire management planning. Current fire weather, fire behaviour and fire danger are updated daily by the National Rural Fire Authority for dissemination via the Internet to fire authorities and the public. The maps are used for short- to medium-term fire management planning applications. The New Zealand Meteorological Service have incorporated the Fire Weather Index System into their forecasting models to produce hourly forecast maps useful for short- term planning and incident management. This is presented to rural fire authorities through their MetConnect web site. These examples are used here to illustrate the essential links between fundamental research on fire behaviour and development of expedient operational fire management solutions. -

ANSFR-Projektets Endelige Rapport: Retningslinjer Til Forbedring Af Brandrisikovurdering Og -Håndtering I Europa

ANSFR-projektets endelige rapport: Retningslinjer til forbedring af brandrisikovurdering og -håndtering i Europa Rapporten er udarbejdet af: Northumberland Fire and Rescue Service (Storbritannien) Frederikssund-Halsnæs Brand- og Redningsberedskab (Danmark) Corpo Nazionale dei Vigili del Fuoco – Nucleo Investigativo Antincendi (Italien) Emergency Services College (Finland) Kanta-Häme Emergency Services (Finland) South West Finland Emergency Services (Finland) Denne rapport dokumenterer ANSFR-projektets anbefalinger. ANSFR- projektet blev medfinansieret af Den Europæiske Union under civilbeskyttelsesinstrumentets indkaldelse af forslag i 2008 (bevillingsnummer : 070401/2008/507848/SUB/A3). Den Europæiske Kommission er ikke ansvarlig for nogen information indeholdt i dette dokument eller noget formål, denne information anvendes til. © Denne publikation, logoer ekskluderet, kan gratis reproduceres i alle formater eller medier til forskning, private studier eller til internt omløb i organisationer. Dette er under forudsætning af, at informationen i denne håndbog reproduceres nøjagtigt og ikke anvendes i en misvisende kontekst. Northumberland Fire and Rescue Service, Frederikssund-Halsnæs Brand- og Redningsberedskab, Corpo Nazionale dei Vigili del Fuoco - Nucleo Investigativo Antincendi og Emergency Services College Finland skal anerkendes som ejerne af materialet indeholdt i denne håndbog, og publikationens titel skal angives. Kontaktoplysning 1 Kontaktoplysninger for yderligere information Hvis du ønsker yderligere information omkring ANSFR-projektet, -

Kinglake National Park Has a Cover of the Area Now Known As Kinglake National Park Is Kinglake National Park Or Visit Eucalypt Forest

For further information Plants and animals Aboriginal People Call Parks Victoria on 13 1963 Most of Kinglake National Park has a cover of The area now known as Kinglake National Park is Kinglake National Park or visit www.parks.vic.gov.au eucalypt forest. You will notice many of the trees located within the traditional land of the showing a green flush of new growth along their Wurundjeri people to the south and the Whittlesea Courthouse Visitor trunks following the fire. This is a survival feature Taungurung people to the north. Information Centre that assists in recovery after loss of foliage, Cnr Beech and Church Streets damage or intense heat. Whittlesea Vic 3757 For many thousands of years Wurundjeri and Tel: (03) 9716 1866 Taungurung people inhabited this area and made Visitor Guide Each species has its own survival features - grass use of the abundance of seasonally available Caring for the environment trees send up their tall flowering spikes full of plants and animals, and to carry-out important Kinglake National Park is the largest national park close to Melbourne. It has 22,360 hectares of tall Help us look after your park seed and tree ferns are protected by thick bark. cultural duties. Plants and animals served many forests, fern gullies and rolling hills, an extensive network of walking tracks and other facilities, as well by following these guidelines: Acacias may survive due to regrowth from root purposes including temporary shelter, transport, suckers and soil stored seed. Gradually other food, medicine, clothing, hunting implements as vantage points offering scenic views. -

Great Forest National Park

The Great Forest National Park An analysis of the economic and social benefits of the proposed Great Forest National Park Hamish Scully Monash University, June 2015 Hamish Scully – June 2015 Great Forest National Park The Great Forest National Park The Proposed Economic and Social Benefits of the proposed Great Forest National Park A Parliamentary Internship Report Prepared for Ms Samantha Dunn MLC, Member for Eastern Metropolitan By Hamish Scully Disclaimer: This report is not an official report of the Parliament of Victoria. Parliamentary Intern Reports are prepared by political science students as part of the requirements for the Victorian Parliamentary Internship Program. The Program is jointly coordinated by the Department of Parliamentary Services through the Parliamentary Library & Information Service and the Organisation Development unit, the University of Melbourne, Monash University, and Victoria University. The views expressed in this report are those of the author. Image on front cover reproduced from: http://www.greatforestnationalpark.com.au/giant-trees.html Page | 2 Hamish Scully – June 2015 Great Forest National Park Acknowledgements I would like to thank Ms Samantha Dunn MLC for her support and guidance during the course of this research. Additionally I would like to thank the co-ordinators of the Victorian Parliamentary Internship. The time and effort of Dr Paul Strangio, Dr Lea Campbell, Dr Julie Stephens, Jon Breukel, Voula Andritsos and Liesel Dumenden has made the production of this report, and the program itself, a very rewarding experience. Page | 3 Hamish Scully – June 2015 Great Forest National Park Executive Summary This report seeks to analyse the economic and social benefits that can be reasonably expected to be derived through the establishment of the proposed Great Forest National Park (GFNP) in the Central Highlands in Melbourne’s northeast. -

Kilmore East Murrindindi Complex South Fire

KILMORE EAST MURRINDINDI COMPLEX SOUTH FIRE BURNED AREA EMERGENCY STABILIZATION PLAN BIODIVERSITY - FAUNA ASSESSMENT I. OBJECTIVES • Assess the effects of fire and suppression actions to the Threatened and Endangered Species of Victoria, Australia under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG Act), and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 • Prescribe emergency stabilization and rehabilitation measures and/or monitoring and assess the effects of these actions to listed species and their designated habitat. II. ISSUES Impacts to Rare or Threatened Species- Seven listed species under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG Act), (Leadbeater’s Possum [Gymnobelideus leadbeateri], Spotted tree-frog [Litora spenceri], Barred Galaxias [Galaxias olidus var. fuscus], Macquarie Perch (Macquaria australasica), Brush-tailed Phascogale [Phascogale tapoatafa], Powerful Owl [Ninox strenua]), Sooty Owl [Tyto tenebricosa], occur within the fire areas. Leadbeater’s Possum, Barred Galaxias, and Macquarie Perch, are also listed nationally under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) within the fire area. Impacts to these species and their habitats from the fire, suppression actions, and proposed emergency stabilization actions are addressed. III. OBSERVATIONS The purpose of this Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) Wildlife Assessment is to document the effects of the fire, suppression activities, proposed stabilization treatments, and potential post fire flooding and sediment delivery to listed threatened and endangered fauna species and their preferred habitats within the fire area. This assessment includes effects to species that occur on lands under the tenure of the Department of Sustainability and Environment, Parks Victoria, Goulburn Broken Water Catchment Management Authority, Goulburn Valley Water, Melbourne Water Corporation, and private ownership. -

Tasman Peninsula

7 A OJ? TASMAN PENINSULA M.R. Banks, E.A. Calholln, RJ. Ford and E. Williams University of Tasmania (MRB and the laie R.J. Ford). b!ewcastle fo rmerly University of Tasmama (EAC) and (ie,a/Ogle,Cl; Survey of Tasmania (E'W) (wjth two text-figures lUld one plate) On Tasman Peninsula, southeastern Tasmania, almost hOrizontal Permian marine and Triassic non-marine lOcks were inllUded by Jurassic dolerite, faulted and overiain by basalt Marine processes operating on the Jurassic and older rocks have prcl(iU!ced with many erosional features widely noted for their grandeur a self-renewing economic asset. Key Words: Tasman Peninsula, Tasmania, Permian, dolerite, erosional coastline, submarine topography. From SMITH, S.J. (Ed.), 1989: IS lllSTORY ENOUGH ? PA ST, PRESENT AND FUTURE USE OF THE RESOURCES OF TA SMAN PENINSULA Royal Society of Tasmania, Hobart: 7-23. INTRODUCTION Coal was discovered ncar Plunkett Point by surveyors Woodward and Hughes in 1833 (GO 33/ Tasman Peninsula is known for its spectacular coastal 16/264·5; TSA) and the seam visited by Captain scenery - cliffs and the great dolerite columns O'Hara Booth on May 23, 1833 (Heard 1981, p.158). which form cliffs in places, These columns were Dr John Lhotsky reported to Sir John Franklin on the first geological features noted on the peninsula. this coal and the coal mining methods in 1837 (CSO Matthew Flinders, who saw the columns in 1798, 5/72/1584; TSA). His thorough report was supported reported (1801, pp.2--3) that the columns at Cape by a coloured map (CSO 5/11/147; TSA) showing Pillar, Tasman Island and Cape "Basaltcs" (Raoul) some outcrops of different rock This map, were "not strictlybasaltes", that they were although not the Australian not the same in form as those Causeway Dictionary of (Vol. -

THE TASMANIAN HERITAGE FESTIVAL COMMUNITY MILESTONES 1 MAY - 31 MAY 2013 National Trust Heritage Festival 2013 Community Milestones

the NatioNal trust presents THE TASMANIAN HERITAGE FESTIVAL COMMUNITY MILESTONES 1 MAY - 31 MAY 2013 national trust heritage Festival 2013 COMMUNITY MILESTONES message From the miNister message From tourism tasmaNia the month-long tasmanian heritage Festival is here again. a full program provides tasmanians and visitors with an opportunity to the tasmanian heritage Festival, throughout may 2013, is sure to be another successful event for thet asmanian Branch of the National participate and to learn more about our fantastic heritage. trust, showcasing a rich tapestry of heritage experiences all around the island. The Tasmanian Heritage Festival has been running for Thanks must go to the National Trust for sustaining the momentum, rising It is important to ‘shine the spotlight’ on heritage and cultural experiences, For visitors, the many different aspects of Tasmania’s heritage provide the over 25 years. Our festival was the first heritage festival to the challenge, and providing us with another full program. Organising a not only for our local communities but also for visitors to Tasmania. stories, settings and memories they will take back, building an appreciation in Australia, with other states and territories following festival of this size is no small task. of Tasmania’s special qualities and place in history. Tasmania’s lead. The month of May is an opportunity to experience and celebrate many Thanks must also go to the wonderful volunteers and all those in the aspects of Tasmania’s heritage. Contemporary life and visitor experiences As a newcomer to the State I’ve quickly gained an appreciation of Tasmania’s The Heritage Festival is coordinated by the National heritage sector who share their piece of Tasmania’s historic heritage with of Tasmania are very much shaped by the island’s many-layered history. -

Lyons Lyons Lyons 8451

BANKS STRAIT C Portland Swan I BASS STRAIT Waterhouse I GREAT MUSSELROE RINGAROOMA BAY BAY Musselroe Bay Rocky Cape C Naturaliste Tomahawk SistersBoat Harbour Beach Beach Table Cape ANDERSON Boat Harbour BAY Gladstone Sisters CreekFlowerdale Stony Head Myalla Wynyard NOLAND Bridport Moorleah Seabrook Lulworth BAY Five Mile Bluff Weymouth Dorset Lapoinya Beechford Bellingham South Somerset Mt Cameron Ansons Bay BURNIE Low Head West Head CPR2484 Calder Low Head Pipers Mt Hicks Brook Oldina Heybridge Greens Pioneer Preolenna Howth Badger Head Beach Lefroy Elliott Mooreville George Town Pipers River Sulphur Creek Devonport Kelso North Winnaleah Herrick Scottsdale FIRES Stowport Penguin Yolla Bell Jetsonville Clarence Point Cuprona ULVERSTONE CPR3658 Bay George Town West Ridgley Leith 2 Beauty Ridgley Upper West Pine Hawley Beach Golconda Blumont Derby DEVONPORT Shearwater Point OF Henrietta Stowport Natone Scottsdale Turners Northdown CPR2472 Takone Camena Port Sorell Nabowla Beach Lebrina Tulendeena Branxholm The Gardens Gawler Don Kayena West Scottsdale Wesley Vale Tonganah Highclere Forth Beaconsfield Weldborough North Tugrah Quoiba Tunnel Riana Thirlstane Sidmouth Springfield Sloop Motton Cuckoo BAY Abbotsham Moriarty Lower Legerwood Lagoon Tewkesbury South Spreyton Latrobe Turners Burnie Riana Eugenana Tarleton Harford West Deviot Marsh Upper Spalford Kindred Melrose Mt Direction Karoola South Ringarooma Binalong Bay Natone Lilydale Springfield Goulds Country CPR2049 Paloona Turners Hampshire CenGunnstral Coast Marsh Plains Sprent Latrobe