Agonistic Behavior in the American Goldfinch1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red Rock Lakes Total Species: National Wildlife Refuge for Birds Seen Not on This List Please Contact the Refuge with Species, Location, Time, and Date

Observer: Address: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Weather: Date: Time: Red Rock Lakes Total Species: National Wildlife Refuge For birds seen not on this list please contact the refuge with species, location, time, and date. Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge Birding Guide 27650B South Valley Road Lima, MT 59739 Red Rock Lakes National [email protected] email Wildlife Refuge and the http://www.fws.gov/redrocks/ 406-276-3536 Centennial Valley, Montana 406-276-3538 fax For Hearing impaired TTY/Voice: 711 State transfer relay service (TRS) U.S Fish & Wildlife Service http://www.fws.gov/ For Refuge Information 1-800-344-WILD(9453) July 2013 The following birds have been observed in the Centennial Valley and are Red Rock Lakes considered rare or accidental. These birds are either observed very infre- quently in highly restrictive habitat types or are out of their normal range. National Wildlife Refuge Artic Loon Black-bellied Plover Winter Wren Clark’s Grebe Snowy Plover Northern Mockingbird Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge is located in the scenic and iso- lated Centennial Valley of southwestern Montana, approximately 40 miles Great Egret Red-necked Phalarope Red-eyed Vireo west of Yellowstone National Park. The refuge has a vast array of habitat, Mute Swan American Woodcock Yellow-breasted Chat ranging from high elevation wetland and prairie at 6,600 feet, to the harsh alpine habitat of the Centennial Mountains at 9,400 feet above sea level. It Black Swan Pectoral Sandpiper Common Grackle is this diverse, marsh-prairie-sagebrush-montane environment that gives Ross’ Goose Dunlin Northern Oriole Red Rock Lakes its unique character. -

Potential Threats to Afro-Palearctic Migrato

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Unravelling the drastic range retraction of an emblematic songbird of North Africa: potential Received: 31 October 2016 Accepted: 16 March 2017 threats to Afro-Palearctic migratory Published: xx xx xxxx birds Rassim Khelifa1, Rabah Zebsa2, Hichem Amari3, Mohammed Khalil Mellal4, Soufyane Bensouilah3, Abdeldjalil Laouar5 & Hayat Mahdjoub1 Understanding how culture may influence biodiversity is fundamental to ensure effective conservation, especially when the practice is local but the implications are global. Despite that, little effort has been devoted to documenting cases of culturally-related biodiversity loss. Here, we investigate the cultural domestication of the European goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) in western Maghreb (Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia) and the effects of long-term poaching of wild populations (1990–2016) on range distribution, socio-economic value, international trading and potential collateral damage on Afro- Palearctic migratory birds. On average, we found that the European goldfinch lost 56.7% of its distribution range in the region which led to the increase of its economic value and establishment of international trading network in western Maghreb. One goldfinch is currently worth nearly a third of the average monthly income in the region. There has been a major change in poaching method around 2010, where poachers started to use mist nets to capture the species. Nearly a third of the 16 bird species captured as by-catch of the European goldfinch poaching are migratory, of which one became regularly sold as cage-bird. These results suggest that Afro-Palearctic migratory birds could be under serious by-catch threat. Species overexploitation for wildlife trade is a major global threat to biodiversity, particularly birds1, 2. -

Mt. Tabor Park Breeding Bird Survey Results 2009

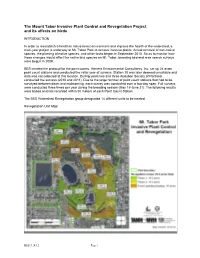

The Mount Tabor Invasive Plant Control and Revegetation Project and its affects on birds INTRODUCTION In order to reestablish a healthier native forest environment and improve the health of the watershed, a multi-year project is underway at Mt. Tabor Park to remove invasive plants. Actual removal of non-native species, the planting of native species, and other tasks began in September 2010. So as to monitor how these changes would affect the native bird species on Mt. Tabor, breeding bird and area search surveys were begun in 2009. BES created the protocol for the point counts. Herrera Environmental Consultants, Inc. set up 24 avian point count stations and conducted the initial year of surveys. Station 10 was later deemed unsuitable and data was not collected at this location. During years two and three Audubon Society of Portland conducted the surveys (2010 and 2011). Due to the large number of point count stations that had to be surveyed between dawn and midmorning, each survey was conducted over a two-day span. Full surveys were conducted three times per year during the breeding season (May 15-June 31). The following results were based on birds recorded within 50 meters of each Point Count Station. The BES Watershed Revegetation group designated 14 different units to be treated. Revegetation Unit Map: BES 3.14.12 Page 1 Point Count Station Location Map: The above map was created by Herrera and shows where the point count stations are located. Point Count Stations are fairly evenly dispersed around Mt. Tabor in a variety of habitats. -

1 Sexual Selection in the American Goldfinch

Sexual Selection in the American Goldfinch (Spinus tristis): Context-Dependent Variation in Female Preference Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Donella S. Bolen, M.S. Graduate Program in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee: Ian M. Hamilton, Advisor J. Andrew Roberts, Advisor Jacqueline Augustine 1 Copyrighted by Donella S. Bolen 2019 2 Abstract Females can vary in their mate choice decisions and this variability can play a key role in evolution by sexual selection. Variability in female preferences can affect the intensity and direction of selection on male sexual traits, as well as explain variation in male reproductive success. I looked at how consistency of female preference can vary for a male sexual trait, song length, and then examined context-dependent situations that may contribute to variation in female preferences. In Chapter 2, I assessed repeatability – a measure of among-individual variation – in preference for male song length in female American goldfinches (Spinus tristis). I found no repeatability in preference for song length but did find an overall preference for shorter songs. I suggest that context, including the social environment, may be important in altering the expression of female preferences. In Chapter 3, I assessed how the choices of other females influence female preference. Mate choice copying, in which female preference for a male increases if he has been observed with other females, has been observed in several non-monogamous birds. However, it is unclear whether mate choice copying occurs in socially monogamous species where there are direct benefits from choosing an unmated male. -

American Goldfinch American Goldfinch Appearance Fairly Small, Slim, Somewhat Small-Headed Bird with a Fairly Long Notched Tail, and Short Conical Bill

American Goldfinch American Goldfinch Appearance Fairly small, slim, somewhat small-headed bird with a fairly long notched tail, and short conical bill. Sexually dimorphic. Male Female Pale pinkish-orange bill. Pale pinkish-orange bill. Black cap, bright yellow body with white undertail coverts; Greenish-yellow crown; bright yellow underparts with white undertail covers; dusky two white wing-bars on black wings. olive/yellow upper parts; two white wing-bars on black wings. Photos: Jackie Tilles (left), Omaksimenko (right) DuPage Birding Club, 2020 2 American Goldfinch Appearance Fairly small, slim, somewhat small-headed bird with a fairly long notched tail and short conical bill. Sexually dimorphic. Female (left) and male (right) Photo: Mike Hamilton DuPage Birding Club, 2020 3 American Goldfinch Appearance Immatures are olive/brown above, pale yellow below, shading to buff on sides and flanks; throat of males progressively brighter yellow with age. Flight feathers dark blackish-brown, males darker than females; wing-bars and feather tips buffy. Immature American Goldfinch Immature American Goldfinch Photos: Mike Hamilton DuPage Birding Club, 2020 4 American Goldfinch Sounds From The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/ SONGS Males sing a long and variable series of twitters and warbles that can be several seconds long. The notes and phrases are variable and repeated in a seemingly random order. Birds continue to learn song patterns throughout life. CALLS The American Goldfinch’s most common call is its contact call, often given in flight. It sounds like the bird is quietly saying po-ta-to-chip or per- chik’-o-ree with a very even cadence. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

Goldfinches and Finch Food!

A Purple Finch (left) en- Frequently Asked Questions joys Sunflower Hearts and About Finch FOOD: an American goldfinch (right, in winter plumage) B i r d s - I - V i e w munches on a 50/50 blend Q. What do Finches eat? of Sunflower heart chips A. Finches utilize many small grass seeds and and Nyjer Seed . flower seed in nature and are built to shell tiny Frequently Asked Questions seeds easily. At Backyard Bird feeders they will Q. Do Goldfinches migrate in winter? FAQ consume Nyjer Seed (traditionally referred to as A. In much of the US, including the Mid- “thistle” in the bird feeding industry, but now west, Goldfinch are year-round residents. about more correctly referred to as “Nyjer”). They also There are areas of the US that only experi- consume Black Oil sunflower Seed and LOVE ence Goldfinch in the Winter and parts of Goldfinches and Sunflower HEARTS whether whole or in fine northern US and Canada only have them chips. In recent years, more and more backyard during breeding season. Check out the nota- Finch Food! birders are feeding Sunflower hearts (which ble difference between the Goldfinch’s does not have a shell) either alone or combined plumage in the winter and during breeding with the traditional Nyjer seed (which DOES season on the cover of this brochure! Q. What other finches can I see at feeders used by Goldfinch? A. Year-round House Finch as well as non- finch family birds like chickadees, tufted Titmouse, and Downy Woodpecker will en- joy your finch feeder. -

British Birds VOLUME 75 NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 1982

British Birds VOLUME 75 NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 1982 Identifying Serins D.J. Holman andS. C. Madge rom descriptions submitted to the Rarities Committee and some Fpersonal experience, it has become apparent that some records of Serins Serinus serinus have referred to escaped cagebirds of other Serinus species, and even to Siskins Carduelis spinus. The purpose of this short paper is to draw attention to the problem and to amplify the specific characters of Serin against those of some of the potentially confusable species. It is beyond the scope of this paper to draw attention to all of the possible pitfall species: there are some 35 species in the genus Serinus, admittedly not all of which could be confused with Serin, and several species of the Neotropical genus Sicalis, two of which resemble Serin in plumage pattern. Specific identification as Serin A bird may be safely identified as Serin by a combination of features: /. Appearance of small, dumpy finch with short bill and 'squat face' Z Short and markedly cleft tail, lacking yellow bases to outer feathers 3. Brownish wings with dark feather centres and pale huffish tips to median and greater coverts, forming one or two wing-bars, and narrow pale edges to tertials in fresh plumage 4. Conspicuous clear bright yellow rump in all plumages (except juvenile, which has streaked rump lacking yellow; one of us (SCM) has seen such a juvenile as late as mid November in European Turkey) 5. Underparts streaked, at least alongflanks, often heavily. Yellow not always present on underparts: if present, restricted to face and breast, with remainder whitish 6. -

An Analysis of Salt Eating in Birds

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1980 An Analysis of Salt Eating in Birds Kathryn Julia Herson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Herson, Kathryn Julia, "An Analysis of Salt Eating in Birds" (1980). Master's Theses. 1909. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1909 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF SALT EATING IN BIRDS by KATHRYN JULIA HERSON A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Biology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1880 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am very graceful for Che advice and help of my thesis committee which conslsced of Dr8, Richard Brewer, Janes Erickson and Michael McCarville, I am parclcularly thankful for my major professor, Dr, Richard Brewer for his extreme diligence and patience In aiding me with Che project. I am also very thankful for all the amateur ornithologists of the Kalamazoo, Michigan, area who allowed me to work on their properties. In this respect I am particularly grateful to Mrs. William McCall of Augusta, Michigan. Last of all I would like to thank all my friends who aided me by lending modes of transportation so that I could pursue the field work. -

First Records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla Coelebs and European Greenfinch Carduelis Chloris from Lord Howe Island

83 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2004, 2I , 83- 85 First Records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris from Lord Howe Island GLENN FRASER 34 George Street, Horsham, Victoria 3400 Summary Details are given of the first records of two species of finch from Lord Howe Island: the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris. These records, from the early 1980s, have been quoted in several papers without the details hav ing been published. My Common Chaffinch records are the first for the species in Australian territory. Details of my records and of other published records of other European finch es on Lord Howe Island are listed, and speculation is made on the origin of these finches. Introduction This paper gives details of the first records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris for Lord Howe Island. The Common Chaffinch records are the first for any Australian territory and although often quoted (e.g. Boles 1988, Hutton 1991, Christidis & Boles 1994), the details have not yet been published. Other finches, the European Goldfinch C. carduelis and Common Redpoll C. fiammea, both rarely reported from Lord Howe Island, were also recorded at about the same time. Lord Howe Island (31 °32'S, 159°06'E) lies c. 800 km north-east of Sydney, N.S.W. It is 600 km from the nearest landfall in New South Wales, and 1200 km from New Zealand. Lord Howe Island is small (only 11 km long x 2.8 km wide) and dominated by two mountains, Mount Lidgbird and Mount Gower, the latter rising to 866 m above sea level. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

FORAGING ECOLOGY AND CALL RELEVANCE DRIVE RELIANCE ON SOCIAL INFORMATION IN AN AVIAN EAVESDROPPING NETWORK By HARRISON HENRY JONES A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Harrison Jones To all those who have given me the inspiration, confidence, and belief to pursue my passion in life ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my parents, who have not only provided unconditional support and encouragement during my degree, but also imbued in me an appreciation for nature and a curiosity about the world. My thanks also go to Elena West, Jill Jankowski, and Rachel Hoang who gave me confidence and the enthusiasm, not to mention sage advice, to apply to a graduate program and follow my passion for ornithology. I would also be remiss to not mention the tremendous support received from the Sieving lab, in particular my amazing officemates Kristen Malone, Willa Chaves, and Andrea Larissa Boesing who were always available to provide help and perspective when needed. I would also like to thank my committee for their helpful input. Katie Sieving was a tremendous help in designing and executing the study, in particular through her knowledge of parid vocalizations. Scott Robinson provided in-depth background knowledge about the study species and insight into the results obtained. And Ben Baiser was invaluable in assisting with the multivariate statistics and generally any other quantitative question I could throw at him. Finally, a big thanks to my many field technicians, Henry Brown, Jason Lackson, Megan Ely, and Florencia Arab, without whom this degree would not be possible.