Rate of Perioperative Neurological Complications After Surgery for Cervical Spinal Cord Stimulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19-0603 ) Issued: January 28, 2020 DEPARTMENT of the TREASURY, ) INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE, ) Holtsville, NY, Employer ) ______)

United States Department of Labor Employees’ Compensation Appeals Board __________________________________________ ) S.L., Appellant ) ) and ) Docket No. 19-0603 ) Issued: January 28, 2020 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY, ) INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE, ) Holtsville, NY, Employer ) __________________________________________ ) Appearances: Case Submitted on the Record Thomas S. Harkins, Esq., for the appellant1 Office of Solicitor, for the Director DECISION AND ORDER Before: CHRISTOPHER J. GODFREY, Chief Judge ALEC J. KOROMILAS, Alternate Judge VALERIE D. EVANS-HARRELL, Alternate Judge JURISDICTION On January 18, 2019 appellant, through counsel, filed a timely appeal from a July 26, 2018 merit decision of the Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs (OWCP). Pursuant to the Federal Employees’ Compensation Act2 (FECA) and 20 C.F.R. §§ 501.2(c) and 501.3, the Board has jurisdiction over the merits of this case.3 1 In all cases in which a representative has been authorized in a matter before the Board, no claim for a fee for legal or other service performed on appeal before the Board is valid unless approved by the Board. 20 C.F.R. § 501.9(e). No contract for a stipulated fee or on a contingent fee basis will be approved by the Board. Id. An attorney or representative’s collection of a fee without the Board’s approval may constitute a misdemeanor, subject to fine or imprisonment for up to one year or both. Id.; see also 18 U.S.C. § 292. Demands for payment of fees to a representative, prior to approval by the Board, may be reported to appropriate authorities for investigation. 2 5 U.S.C. -

Neck and Headache Pain

Neck and Headache Pain ICD-9-CM code: 723.2 cervicocranial syndrome ICF codes: Activities and Participation Domain code: d4158 Maintaining a body position, other specified - specified as: maintaining the head in a flexed position, such as when reading a book; or, maintaining the head in an extended position, such as when looking up at a computer screen or video monitor Body Structure codes: s7103 Joints of head and neck region Body Functions code: b28010 Pain in head and neck Common Historical Findings: Unilateral neck pain with referral to occipital, temporal, parietal, frontal or orbital areas Headache precipitated or aggravated by neck movements or sustained positions Noncontinuous headaches (usually < 1 episode/day; < 2 episodes/week) Common Impairment Findings - Related to the Reported Activity Limitation or Participation Restrictions: Observable postural asymmetry of the head on neck (sidebent or extended) Headache reproduced with provocation of the involved segmental myofascia and/or joints O/C1, C1/C2, or C2/C3 restricted accessory motions with associated myofascial trigger points Physical Examination Procedures: Palpation/Provocation of Suboccipital Myofascia Joe Godges DPT, MA, OCS 1 KP So Cal Ortho PT Residency O/C1, C1/C2, or C2/C3 accessory motion testing using posterior-to-anterior pressures 0/C1 accessory motion testing using C1 lateral translatoty pressures C1 – C2 Rotation ROM testing with the C2 – C7 segments in flexion Joe Godges DPT, MA, OCS 2 KP So Cal Ortho PT Residency Neck and Headache Pain: Description, Etiology, Stages, and Intervention Strategies The below description is consistent with descriptions of clinical patterns associated with the term “Cervicogenic Headache.” Description: Cervicogenic headache is a headache where the source of the ache is from a structure in the cervical spine, such as a cervical facet, muscle, ligament, or dura. -

A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

MYOFASCIAL TRIGGER POINTS AND INNERVATION ZONE LOCATIONS IN UPPER TRAPEZIUS MUSCLES MARCO BARBERO A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy QUEEN MARGARET UNIVERSITY 2016 1 ABSTRACT Myofascial pain syndrome is characterized by sensory, motor and autonomic symptoms, and a myofascial trigger point (MTrP) is considered the principal clinical feature. Clinicians recognise myofascial pain syndrome as an important clinical entity but many basic and clinical issues need further research. Electrophysiological studies indicate that abnormal electrical activity is detectable near MTrPs. This phenomenon has been described as endplate noise and it has been purported to be associated MTrP pathophysiology. Authors also suggest that MTrPs are located in the innervation zone (IZ) of muscles. The aim of this thesis was to describe both the location of MTrP and the IZ’ locations in the upper trapezius muscle. The hypothesis was that distance between the IZ and the MTrP in upper trapezius muscle is equal to zero. This thesis includes two preliminary studies. The first one address the reliability of surface electromyography (EMG) in locating the IZ in upper trapezius muscle, and the second one address the reliability of a manual palpation protocol in locating the MTrP in upper trapezius muscle. The intra- rater reliability of surface EMG in locating the IZ was almost perfect; with Kappa = 0.90 for operator A and Kappa = 0.92 for operator B. Also the inter- rater reliability showed an almost perfect agreement, with Kappa = 0.82. Both the operators conducted 900 estimations of IZ’ location through visual analysis of the EMG signals. -

Appendix 4: Code Groups from ICPC-2 and ICPC-2 PLUS Reasons for Encounter and Problems Managed

Appendix 4: Code groups from ICPC-2 and ICPC-2 PLUS Reasons for encounter and problems managed ............................................................................................. 2 Table A4.1: Code groups from ICPC-2 and ICPC-2 PLUS – reasons for encounter and problems managed ................................................................................................................. 2 Table A4.2: Code groups from ICPC-2 and ICPC-2 PLUS – chronic problems .................................. 7 Table A4.3: Code groups from ICPC-2 and ICPC-2 PLUS – problems managed by practice nurses ..................................................................................................................................... 11 Other treatments ................................................................................................................................................. 12 Table A4.4: Code groups from ICPC-2 and ICPC-2 PLUS – clinical treatments ............................... 12 Table A4.5: Code groups from ICPC-2 and ICPC-2 PLUS – procedures ........................................... 17 Table A4.6: Code groups from ICPC-2 and ICPC-2 PLUS – clinical measurements ........................ 19 Referrals ............................................................................................................................................................... 20 Table A4.7: Code groups from ICPC-2 and ICPC-2 PLUS – referrals ................................................ 20 Pathology test orders ........................................................................................................................................ -

Concussion and Migraine Update

Dr. Mark Saracino 1150 First Avenue, Suite 120 Board Certified King of Prussia PA 19406 1341 Chiropractic Neurologist 610 337 3335 voice 610 337 4858 fax [email protected] www.DrSaracino.com In advance of a lecture I was asked to give September 2019 to 500 Pennsylvania attorneys whom work with patients with concussions, I created this list of updated concussion and migraine codes all doctors can use. The updates have empowered us to justify our suspicions that far-reaching complaints are often caused by concussions and migraines. A few years ago, the codes doctors use to label diseases was upgraded. To we chiropractic and medical neurologist's satisfaction, many of the symptoms that accompany concussions, migraines and severe headaches, such as abdominal complaints like nausea (G43.DO), visual changes causing double-vision and eye pain (G43.B) and mental-state changes of mental fatigue while concentrating and personality changes not experienced prior (R41.9), were included in the new codes. These revised codes were more inclusive and they, in some respects, justified our long-time recognition of the complications of concussion (SO6. ...), migraines (G43. ...) and headaches. The list below shows just a few of the updated conditions that were not well understood not long ago and ones seen in my patient population. Our understanding of concussions and other head-origin complaints is growing. ICD-10 Cranial (head) Diagnostic Codes R51 Headache & Facial px: chronic or daily M53.0 Cervicocranial syndrome G43.C0 Periodic headache syndromes -

Healthworks! Icd 9 Cm

ICD 9 CM HEALTHWORKS! ICD 9 CM CERVICAL LUMBAR (Cont’d) GENERAL (Cont’d) 353.0 Cerv. Rib Synd 724.4 Lumbosacral Radiculitis 728.4 Laxity of Ligaments Scalenus Anticus Synd 724.5 Vertebrogenic Pain Syndrome 728.85 Spasm of Muscle Costoclavicular Synd 724.6 Lumbosacral Instability 729.9 Fibromyalgia 721.0 Cervical Spondylosis w/o Myelopathy Sacroiliac Instability 729.2 Neuritis / Neuralgia (Unspecified) 721.1 Vertebral Artery Compression Synd 724.9 Lumbar Facet Syndrome 731.0 Paget’s Disease 722.0 Cervical Disc Syndrome 729.1 Myalgia / Myositis 736.81 Short Leg - Acquired 722.4 Degenerative Disc Disease 737.20 Lumbar Lordosis 737.3 Scoliosis (Idiopathic) 722.71 Cervical Disc Synd w/ Myelopathy 756.10 Anomaly (Unspecified) 755.3 Short Leg - Congenital 722.81 Postlaminectomy Syndrome 756.11 Lumbosacral Spondylolysis 756.16 Klippel-Feil Syndrome 723.1 Cervicalgia 756.12 Spondylolisthesis (Grade 1,2,3,4) Knife Clasp Syndrome 723.2 Cervicocranial Syndrome 756.17 Spina Bifida Occulta 756.17 Spina Bifida Occulta 723.3 Cervicobrachial Syndrome 756.19 Supernumerary Vertebra 756.19 Supernumerary Vertebra 723.4 Cervical Radiculitis 805.4 Lumbar Fracture 780.4 Dizziness/Vertigo/Lightheadedness 723.5 Torticollis 839.20 Lumbar Subluxation 780.5 Sleep Disturbance 729.1 Myalgia / Myositis 839.42 Sacroiliac Subluxation 780.7 Fatigue / Malaise 737.41 Cervical Kyphosis 846.0 Lumbosacral Sprain/Strain Synd. 781.0 Involuntary Tremors / Spasm 756.15 Vertebral Fusion (Congenital) 847.20 Lumbar Sprain/Strain Syndrome 781.2 Paralytic/Spastic/Staggering Gait 756.2 -

1 Table 1. List of Read Codes Used in the Studies of Anxiety

Table 1. List of Read codes used in the studies of anxiety. Number of Read code Description studies Eu41.00 [X]Other anxiety disorders 5 Eu41100 [X]Generalized anxiety disorder 5 Eu41z11 [X]Anxiety NOS 5 Eu41000 [X]Panic disorder [episodic paroxysmal anxiety] 4 Eu05400 [X]Organic anxiety disorder 4 Eu41112 [X]Anxiety reaction 4 Eu41111 [X]Anxiety neurosis 4 Eu41z00 [X]Anxiety disorder, unspecified 4 E202.12 Phobic anxiety 4 E200200 Generalised anxiety disorder 4 E200.00 Anxiety states 4 E200000 Anxiety state unspecified 4 E200z00 Anxiety state NOS 4 Eu40.00 [X]Phobic anxiety disorders 3 Eu40z00 [X]Phobic anxiety disorder, unspecified 3 Eu41012 [X]Panic state 3 Eu41011 [X]Panic attack 3 Eu41y00 [X]Other specified anxiety disorders 3 Eu41300 [X]Other mixed anxiety disorders 3 Eu41211 [X]Mild anxiety depression 3 Eu41113 [X]Anxiety state 3 E200500 Recurrent anxiety 3 E200100 Panic disorder 3 E200111 Panic attack 3 E200400 Chronic anxiety 3 1B1V.00 C/O - panic attack 3 1B13.11 Anxiousness - symptom 3 1B13.00 Anxiousness 3 E200300 Anxiety with depression 3 Eu93200 [X]Social anxiety disorder of childhood 2 Eu34114 [X]Persistant anxiety depression 2 Eu40012 [X]Panic disorder with agoraphobia 2 Eu40y00 [X]Other phobic anxiety disorders 2 Eu41200 [X]Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder 2 Eu93y12 [X]Childhood overanxious disorder 2 Eu41y11 [X]Anxiety hysteria 2 E2D0.00 Disturbance of anxiety and fearfulness childhood/adolescent 2 E2D0z00 Disturbance anxiety and fearfulness childhood/adolescent NOS 2 E202100 Agoraphobia with panic attacks 2 E292400 -

Classification and Treatment of Chronic Daily Headache

Managing Challenging Headaches: Classification and Treatment of Chronic Daily Headache Zahid H. Bajwa, M.D. Director, Boston Headache Institute Director, Clinical Research, Boston PainCare [email protected] BOARD CERTIFICATION American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN-Neurology) Board Certified in Pain Medicine (ABA-ABPN) American Board of Pain Medicine UCNS Certified in Headache Medicine Zahid Bajwa, MD Disclosures: Research Support: Amgen Contributor, UptoDate, Headache and Pain Sections Textbook “Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine” 2nd and 3rd Ed with Mc-Graw Hill Consultant: AstraZeneca, DepoMed, TEVA, DMSB: Boston Scientific for SCS Consultant: GLG, MEDACorp, McKinsey, Guidepoint This session will discuss off-label use of drugs Learning Objectives Review HA classification Identifying episodic vs chronic migraine Treatments for episodic migraine Treatments for chronic migraine With Meds, NBs, BTX The role of CBT in migraine treatment Self Assessment Question 1. Which of the following treatments were approved by the FDA for chronic migraine? A. Depakote B. Topamax C. OnabotulinumtoxinA D. Nerve Blocks E. Beta Blockers Self Assessment Question 2. Oxygen therapy is more helpful for…? A. Chronic daily headaches B. Acute Migraine attack C. Cluster headaches D. Cervicogenic headaches E. Temporal arthritis ICDH Classification of CDH Chronic migraine headache Chronic tension-type headache Medication overuse headache Hemicrania continua New daily persistent headache Medically intractable chronic headaches CDH – chronic -

Diagnosis List

Diagnosis Code List Description Code GASTRITIS NERVOUS 306.4 TENSION HEADACHE 307.81 NEUROVASCULAR COMPRESSION SYNDROME 336.9 SYMPATHETIC COMPRESSION 337.9 MIGRAINE HEADACHE 346.0 ATYPICAL MIGRAINE 346.1 CLUSTER HEADACHE 346.2 TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA 350.1 BELLS PALSY 351.0 IRRITATION OF BRACHIAL PLEXUS 353.0 CERVICAL NERVE ROOT IRRITATION 353.2 THORACIC NERVE ROOT IRRITATION 353.3 COMPRESSION OF LUMBOSACRAL PLEXUS 353.4 INTERCOSTAL NEURALGIA THORACIC SPINE 353.8 CARPAL TUNNEL SYNDROME 354.0 INTERCOSTAL NEURALGIA 354.8 VISUAL DISTURBANCE UNSPECIFIED 368.9 VERTIGO 386.0 TINNITUS UNSPECIFIED 388.30 HYPERTENSION 401.9 ACUTE SINUSITIS UNSPECIFIED 461.9 BRONCHITIS 466.0 ASTHMA BRONCHIAL 493.9 TMJ JOINT DYSFUNCTION 524.6 GASTRITIS 535.1 COLITIS CHRONIC 558.9 CONSTIPATION 564.0 DYSMENORRHEA 625.3 COMPRESSION FRX CERVICAL VERTEBRAE 705.0 DEGENERATIVE JOINT DISEASE 715.9 TRAUMATIC ARTHROPATHY SPINE 716.18 MEDIAL MENISCUS TEAR OF KNEE 717.3 CALCIUM DEPOSITS IN JOINTS 718.10 WHIPLASH INJURY TO NECK 718.88 EFFUSION OF KNEE 719.06 Page: 1 Diagnosis Code List Description Code JOINT STIFFNESS 719.20 ELBOW SYNOVITIS 719.22 SHOULDER JOINT ARTHRALGIA 719.41 STIFFNESS IN SPINAL JOINT 719.50 SHOULDER STIFFNESS 719.51 ELBOW STIFFNESS 719.53 HAND STIFFNESS 719.54 HIP STIFFNESS 719.55 KNEE STIFFNESS 719.56 ANKLE OR FOOT STIFFNESS 719.57 WALKING DIFFICULTY 719.7 SPINAL ENTHESOPATHIES 720.1 SACROILIITIS 720.2 SPONDYLITIS 720.9 CERVICAL OSTEOARTHRITIS 721.0 CERVICAL SPONDYLOSIS W MYELOPATHY 721.1 THROACIC OSTEOARTHRITIS 721.2 LUMBAR OSTEOARTHRITIS 721.3 THORACIC -

VSC Position Statment Edit

Alliance of UK CHIROPRACTORS THE VERTEBRAL SUBLUXATION COMPLEX The History, Science, Evolution and Current Quantum Thinking on a Chiropractic Tenet 17th August 2010 Commissioned on behalf of the Alliance of UK Chiropractors (AUKC) UNITED CHIROPRACTIC ASSOCIATION Working Group Ross McDonald, DC Christopher Kent, DC Bruce Lipton, PhD Matthew McCoy, DC Peter Rome, DC !&!$! &$!+$%%%*% +!+ $!"$'%&-%& !+$&$ **-'! 1 ,"!" & &$% !+ !$ **-'! + !%!$%&!+&"$%%! &&77 &+$&$ **-'! %&&!%!7$ 7$!*",& &$!"$'"$!%%! ! &.&! !*%&!$.!%**-'! %"!*%.$.$!"$&!$%1 !$&* &.&% %$ &.!&% &,$! !&$!"$'%%!'! % &$!"$' !%+ &-%& !& +$%%&& &%%. &&&$% ! + !$& +!+ &!& 3& %%35 !& !&&&$'! .*%$!"$' &$0%4%61$$!&%"!%'! %&$&!*&,& &"$!%%! 0$ &+ &% +&&&&% !&-%& !& &$%$%*%& '' &%-%& % 2$3"$&*$$!! &"!$$.$!"$' *$$ &!&& 1 &""$%&&&%%! . $!* %*%#* &$%!%&& &%%!$"!'. %& % '.%1 $+, &$&*$"$% &.!&$!$ %'! %0& $ $!"$'!* $+ &*'! $+,$%+!% &! ,,&&$%$% $&$& %%%%&&&$% + !$&-%& !&$&$ **-'! !"-1 + &!&! &$$.0&&%0%*""!$' &&&&$% !%*& %& 0% !&.& !$&! 1 &%%! '! $#* &. %*%%! %! &%%*&&&&+ !&%! .$$ +$'% & %%&.!$+ &&+! % !$$&!% +$'% 1 % $%%&,!"!$& &"! &%,,$!+$!!, &%%! + !&,%"$!*1 $%&.0! !&+$'%,&! !%0&%! %'&*&%&'! ! %!"!"$' !)$ ,&.%&&1 ! .0 "$"%!$"!$& &.+ &*$$ &&0&!".+ 5 6%&&%&&&!* %$$! %+ !$%.$!"$&!$%0&. $ !&-*%+.$! 5"" -861 $% !%*%#* &+ !&$%. &!!*$ !,,%&&%!&$,%1&%'&%+ !&,%$%.1 *(#;)0"03+%$<)"%$)*%(4$*"$(*)"*(*0(9%($*%"#$*2) 0)**+#%&&%(*)2"*(")*$")$+%$)-(0**%$""%"#$CGII9 %"#$)0"03+%$);)"%+%$%(&0.$%0*% %4$*9<*!$)$((-((*%CHFG $+%$%**(#9#-()0(*(%#&"*4*1()((4%"*($+1*(#)0)*% )()0"03+%$9%# -

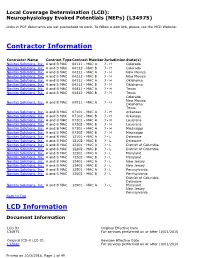

Local Coverage Determination for Neurophysiology Evoked Potentials

Local Coverage Determination (LCD): Neurophysiology Evoked Potentials (NEPs) (L34975) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information Contractor Name Contract Type Contract Number Jurisdiction State(s) Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 04111 - MAC A J - H Colorado Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 04112 - MAC B J - H Colorado Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 04211 - MAC A J - H New Mexico Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 04212 - MAC B J - H New Mexico Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 04311 - MAC A J - H Oklahoma Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 04312 - MAC B J - H Oklahoma Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 04411 - MAC A J - H Texas Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 04412 - MAC B J - H Texas Colorado New Mexico Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 04911 - MAC A J - H Oklahoma Texas Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 07101 - MAC A J - H Arkansas Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 07102 - MAC B J - H Arkansas Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 07201 - MAC A J - H Louisiana Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 07202 - MAC B J - H Louisiana Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 07301 - MAC A J - H Mississippi Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 07302 - MAC B J - H Mississippi Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 12101 - MAC A J - L Delaware Novitas Solutions, Inc. A and B MAC 12102 - MAC B J - L Delaware Novitas Solutions, Inc. -

IAC Ch 78, P.1 441—78.8(249A) Chiropractors. Payment Will Be

IAC Ch 78, p.1 441—78.8(249A) Chiropractors. Payment will be made for the same chiropractic procedures payable under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act (Medicare). 78.8(1) Covered services. Chiropractic manipulative therapy (CMT) eligible for reimbursement is specifically limited by Medicaid to the manual manipulation (i.e., by use of the hands) of the spine for the purpose of correcting a subluxation demonstrated by X-ray. Subluxation means an incomplete dislocation, off-centering, misalignment, fixation, or abnormal spacing of the vertebrae. 78.8(2) Indications and limitations of coverage. a. The subluxation must have resulted in a neuromusculoskeletal condition set forth in the table below for which CMT is appropriate treatment. The symptoms must be directly related to the subluxation that has been diagnosed. The mere statement or diagnosis of “pain” is not sufficient to support the medical necessity of CMT. CMT must have a direct therapeutic relationship to the patient’s condition. No other diagnostic or therapeutic service furnished by a chiropractor is covered under the Medicaid program. ICD-9 CATEGORY I ICD-9 CATEGORY II ICD-9 CATEGORY III 307.81 Tension headache 353.0 Brachial plexus lesions 721.7 Traumatic spondylopathy 721.0 Cervical spondylosis 353.1 Lumbosacral plexus 722.0 Displacement of cervical without myelopathy lesions intervertebral disc without myelopathy 721.2 Thoracic spondylosis 353.2 Cervical root lesions, NEC 722.10 Displacement of lumbar without myelopathy intervertebral disc without myelopathy 721.3 Lumbosacral