Conceiving Migration and Communication in a Global Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RE-THINKING METHODOLOGY IPCC2018 Interdisciplinary Phd

YÖNTEMİ YENİDEN DÜŞÜNMEK IPCC2018 Disiplinlerarası Doktora Öğrencileri İletişim Konferansı İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi, İletişim Bilimleri Doktora Programı 28-29 Mayıs santralistanbul Kampüsü RE-THINKING METHODOLOGY IPCC2018 Interdisciplinary PhD Communication Conference İstanbul Bilgi University, PhD in Communication Program May 28-29 santralistanbul Campus Scientific Committee Aslı Tunç Asu Aksoy Barış Ursavaş Emine Eser Gegez Erkan Saka Esra Ercan Bilgiç Feride Çiçekoğlu Feyda Sayan Cengiz Gonca Günay Gökçe Dervişoğlu Halil Nalçaoğlu Itır Erhart Nazan Haydari Pakkan Serhan Ada Yonca Aslanbay Organization Committee Adil Serhan Şahin Can Koçak Dilek Gürsoy Melike Özmen Onur Sesigür Book and Cover Design: Melike Özmen Web Design: Dilek Gürsoy Proofreading: Can Koçak http://ipcc.bilgi.edu.tr [email protected] ipcc2018 ipcc2018 with their contribution: Reflections on IPCC2018 Re-Thinking Methodology Nazan Haydari “This is a call from a group of doctoral students for the doctoral students sharing similar concerns about the lack of feedback and interaction in large conferences and in quest for opportunities of building strong and continuous academic connections. We would like to invite you collaboratively discuss and redefine our researches, and methodologies. We believe in the value of constructive feedback in the various stages of our researches”. (CFP of IPCC 2018) Conferences are significant spaces of knowledge production bringing variety of concerns and approaches together. This intellectual attempt carries the greatest value, as Margaret Mead* pointed out only when the shift from one-to-many/single channel communication to many-to-many/multimodal communication is taken for granted. Nowadays, in parallel to increasing number of national and international conferences, a perception about the size of the conference being in close relationship with the quality of the conferences has developed. -

SEZİN ÖNER Address

SEZİN ÖNER Address: Kadir Has University Department of Psychology Kadir Has Cad., Cibali Fatih, 34083 İstanbul – Turkey Email: [email protected] Tel: +90-212- 533 65 32 (1667 ext.) EDUCATION PhD - Cognitive Psychology (2012-2016) Koç University, Istanbul M.A. - Clinical Psychology (2009-2011) Doğuş University, Istanbul B.A. - Psychology, 2006-2009 Boğaziçi University, Istanbul, PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Assistant Professor (2017 - ) Kadir Has University, Department of Psychology Post-Doctoral Research Fellow (2016 – 2017) Koç University, Department of Psychology Research & Teaching Assistant (2012 – 2016) Koç University, Department of Psychology Visiting Researcher (2014 – 2015) Duke University, Department of Psychology Research Assistant (2009 –2012) Doğuş University, Department of Psychology Researcher (2010 – 2012) The role of adult attachment in communication patterns in dating adults Trainer (2010 – 2011) Effective parenting training for female inmates Trainer & Researcher (2010) Psychological assessment for substance-dependent inmates Researcher (2008 – 2009) Boğaziçi University, Adaptation of Attachment Q-Sort Researcher (2006 - 2007) Boğaziçi University, Cognitive assessment in preschool children PUBLICATIONS Öner, S. & Gülgöz, S. (in press). Otobiyografik hatırlamanın duygu düzenleme işlevi, Türk Psikoloji Dergisi. Ece, B., Öner, S., Demiray, B. & Gülgöz, S. (in press). Comparison of Earliest and Later Autobiographical Memories in Young and Middle-Aged Adults. Studies in Psychology Öner, S. (2017). Neural substrates of cognitive emotion regulation: A brief review. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 28 (1), 91-96 Öner, S. & Gülgöz, S. (2017). Remembering successes and failures: rehearsal characteristics influence recollection and distancing. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, doi: 10.1080/20445911.2017.1406489. Öner, S. & Gülgöz, S. (2017). Autobiographical remembering regulates emotions: A functional perspective. Memory, doi: 10.1080/09658211.2017.1316510. -

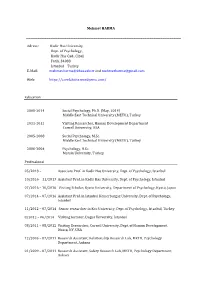

Mehmet HARMA Adress: Kadir Has University

Mehmet HARMA Adress: Kadir Has University Dept. of Psychology, Kadir Has Cad., Cibali Fatih, 34083 Istanbul – Turkey E-Mail: [email protected] and [email protected] Web: https://corelab.khas.edu.tr Education 2008-2014 Social Psychology, Ph.D. (May, 2014) Middle East Technical University (METU), Turkey 2011-2012 Visiting Researcher, Human Development Department Cornell University, USA 2005-2008 Social Psychology, M.Sc. Middle East Technical University (METU), Turkey 2000-2004 Psychology, B.Sc. Mersin University, Turkey Professional 05/2018 – Associate Prof. in Kadir Has University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 10/2016 – 11/2017 Assistant Prof. in Kadir Has University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 07/2016 – 10/2016 Visiting Scholar, Kyoto University, Department of Psychology, Kyoto, Japan 07/2014 – 07/2016 Assistant Prof. in Istanbul Kemerburgaz University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 11/2012 – 07/2014 Senior researcher in Koc University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul, Turkey 8/2012 – 06/2014 Visiting lecturer, Dogus University, Istanbul 08/2011 – 08/2012 Visiting Researcher, Cornell University, Dept. of Human Development, Ithaca, NY, USA 12/2005 – 07/2011 Research Assistant, Relationship Research Lab, METU, Psychology Department, Ankara 01/2009 – 07/2011 Research Assistant, Safety Research Lab, METU, Psychology Department, Ankara 02/2010 – 07/2010 Teaching Assistant, METU Psychology Department, Advance d Design and Statistical Procedures in the Assessment of Psychological Change; Graduate Course 09/2009 – 01/2010 Teaching -

Unige-Republic of Turkey: a Review of Turkish Higher Education and Opportunities for Partnerships

UNIGE-REPUBLIC OF TURKEY: A REVIEW OF TURKISH HIGHER EDUCATION AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR PARTNERSHIPS Written by Etienne Michaud University of Geneva International Relations Office October 2015 UNIGE - Turkey: A Review of Turkish Higher Education and Opportunities for Partnerships Table of content 1. CONTEXTUALIZATION ................................................................................................... 3 2. EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM ................................................................................................ 5 2.1. STRUCTURE ................................................................................................................. 5 2.2. GOVERNANCE AND ACADEMIC FREEDOM ....................................................................... 6 3. INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS ....................................................................................... 7 3.1. ACADEMIC COOPERATION ............................................................................................. 7 3.2. RESEARCH COOPERATION ............................................................................................ 9 3.3. DEGREE-SEEKING MOBILITY ........................................................................................ 10 3.4. MOBILITY SCHOLARSHIPS ........................................................................................... 11 3.5. INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCES AND FAIRS .................................................................. 12 3.6. RANKINGS ................................................................................................................. -

Sakarya University 2019-2020 Academic Year International Students

SAKARYA UNIVERSITY 2019-2020 ACADEMIC YEAR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS ADMISSION PRINCIPLES THE TIME SCHEDULE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS ADMISSION Online Application 20 May -23 June 2019 Announcement of Accepted Students 16 July 2019 Registration Dates 17 July-09 August 2019 ADDITIONAL PLACEMENT Online Application 26 August-08 September 2019 Announcement of Accepted Students 23 September 2019 Registration Dates 24 September-11 October 2019 1. TERMS OF APPLICATION (Presidency of Higher Education Council General Principles For International Students Admission) Who can apply? a) On the condition that they are final year students at High school or already graduate. 1) 1) Foreign Nationals 2) Turkish citizen by birth but permitted to be denationalized by the ministry of internal affairs (blue card holders) 3) Those foreigners by birth but becoming Turkish citizens afterwards/ dual citizens under this circumstance. 4) Those who completing their secondary education in a foreign country (apart from TRNC) including students finishing their educations abroad (apart from TRNC) at Turkish schools operating under the Ministry of Education (MEB), WHO CANNOT APPLY? 1) Those who hold Turkish citizenship but completing whole high school education in Turkey or TRNC, 2) Those who hold the citizenship of the TRNC (Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus) 3) Who hold a dual citizenship one of which is Citizenship of Republic of Turkey by birth as defined in the article a item 2 (except for those fulfilling the requirements article a item 4) 4)Those who hold the citizenship of TR or a dual citizenship, one of which is the citizenship of the TR by birth, as stated in article 2 item a ,and who have completed their secondary education at institutions with an embassy or in other foreign institution in Turkey. -

The 6Th Intraders International Conference on International Trade

The 6th InTraders International Conference on International Trade Proceeding Book EDITORIAL BOARD Assoc. Prof. Dr. Leena Jenefa Mamoona Rasheed Kürşat Çapraz InTraders Academic Platform www.intraders.org Publisher Kürşat ÇAPRAZ e-ISBN: 978-605-69427-6-1 Editorial Board Assoc. Prof. Dr. Leena Jenefa, India Mamoona Rasheed, Pakistan Kürşat ÇAPRAZ, Turkey e-ISBN: 978-605-69427-6-1 Edition: First Edition 21 December 2020 Sakarya, Turkey Language: English © All rights reserved. The copyright of this book belongs to Kürşat ÇAPRAZ, who published the book according to the provisions of Turkish Law No. 5846. Not sold with money. It cannot be reproduced or copied by any electronic or mechanical recording system or photocopy without the permission of the publisher. However, short citation can be made by showing the source. University Libraries and similar public institutions may add books to databases provided that they are open and free access without permission. Publisher Kürşat ÇAPRAZ InTraders Academic Platform Sakarya University Faculty of Political Sciences. Serdivan Sakarya, Turkey www.intraders.org [email protected] The 6th InTraders International Conference on International Trade Proceeding Book 5-9 October 2020 (e-conference) https://www.intraders.org/october e-ISBN: 978-605-69427-6-1 1 Regultory Board Kürşat ÇAPRAZ Sakarya University Turkey Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ekrem ERDOĞAN Sakarya University Turkey Prof.Dr. ADRIANA SCHIOPOIU University of Craiova Romania BURLEA Ph.D. Faculty Member Mustafa YILMAZ Sakarya University of Applied Turkey Sciences Prof. Dr. Georgeta Soava University of Craiova Romania Dr. Laurentiu Stelian MIHAI University of Craiova Romania Ph.D. Faculty Member Catalin Aurelian University of Craiova Romania Rosculete Lect. -

Comparison Member and Candidate Countries to the European Union by Means of Main Health Indicators∗

China-USA Business Review, ISSN 1537-1514 April 2012, Vol. 11, No. 4, 556-563 D D AV I D PUBLISHING Comparison Member and Candidate Countries to the European ∗ Union by Means of Main Health Indicators Fatma Lorcu Trakya University, Edirne, Turkey Bilge Acar Bolat Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey Throughout history, health policies and the institutionalization of health care have taken shape according to political and economic conditions, social structures and value systems of societies, as well as to their needs and changes in health conditions. Today, economic development is addressed from a different approach in which the issue of health plays an important part. With a focus on the health sector’s role in development, this new approach has increased the importance of this sector of government and of life, allowing data on health to be included in many countries’ development indicators. The aim of this study is to identify the differences between EU former member states, member states, and candidate countries (including Turkey) in terms of health indicators that have become the key indicators of social and economic development. In this study, discriminant analysis will be used in order to analyse the differences between the European Union (EU) countries, and candidate countries in terms of main health indicators. Under-five mortality rate (‰), health expenditure per capita (PPP US$), total expenditure on health as percent of gross domestic product expenditure (percentage of GDP), immunization coverage among one-year-olds with one dose of measles (%), prevalence of current tobacco use among adults (≥ 15 years) (%), per capita recorded alcohol consumption (litres of pure alcohol) among adults, total fertility rate (%), hospital beds (per 1,000 population), physicians (per 1,000 population) and life expectancy are all included in the analysis as main health indicators of a country’s fitness for acceptance into the EU. -

CV Name: Sibel Sakarya (Kalaca) Place and Date of Birth: Istanbul

CV Name: Sibel Sakarya (Kalaca) Place and date of birth: Istanbul, 1966 Educational background: Undergraduate education: Ege University School of Medicine, İzmir-Turkey, 1983-1989 Postgraduate education: • Public Health Speciality: Public Health, Hacettepe University, School of Medicine, Ankara-Turkey; 1992-1996 • Master of Public Health: Hebrew University, Braun School of Public Health, Jerusalem, Israil, 1997-1998 • Master of Health Professionals Education: Maastricht University, The Netherlands, 2001- 2006 Working Experience: Position Place Year Full Professor Marmara University School of Medicine, Department 2011- of Public Health-Istanbul-Turkey Associate Professor Marmara University School of Medicine, Department 2005-2011 of Public Health- Istanbul-Turkey Assistant Professor Marmara University School of Medicine, Department 2000-2004 of Public Health- Istanbul-Turkey Lecturer Marmara University School of Medicine, Department 1996-1999 of Public Health- Istanbul-Turkey Resident Hacettepe University School of Medicine, Department 1992-1996 of Public Health- Ankara-Turkey General Practititoner State- Pediatric Hospital -Ankara- Turkey 1990-1992 General Practititoner Health Center- Kastamonu-Turkey 1989-1990 Areas of interest: • Noncommunicable Diseases (Epidemiology) • Health Promotion • Qualitative Research Methods • Gender and Health (Women’s Health) Professional activities Editor in Chief: Turkish Journal of Public Health, 2009-… Associate Editor: International Journal of Public Health, 2014- Biostatistics Editor: Clinical and -

Ties to Technoparks and University Characteristics in Turkey

Volume 8, Number 1, 2021, 97{117 journal homepage: region.ersa.org DOI: 10.18335/region.v8i1.300 ISSN: 2409-5370 Linking the Performance of Entrepreneurial Universities to Technoparks and University Characteristics in Turkey Tuzin Baycan1, Gokcen Arkali Olcay2 1 Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey 2 Gebze Technical University, Gebze, Turkey Received: 10 January 2020/Accepted: 2 December 2020 Abstract. Universities' third mission of knowledge commercialization imposes them a core role towards becoming entrepreneurial universities in the triple helix interacting with the government and industry. Entrepreneurial universities have crucial functions of providing entrepreneurial support infrastructure for innovation and engaging in the regional economy. Technoparks, in that sense, form an essential channel for universities to disseminate and commercialize the knowledge considering their geographical proximity and facilitating mechanisms. Measuring the performances of entrepreneurial universities and technoparks in quantitative metrics have been initiated by different government agencies in Turkey, which resulted in two different indices. The Most Entrepreneurial and Innovative University Index and the Performance Index for Technoparks track performances annually. Using the data provided by the two indices, this study explores how the technoparks' performance can be linked to the universities' scores in entrepreneurship and innovation, along with some university-specific characteristics and their interactions. The geographical proximity provided by the technoparks contributes to the performance of entrepreneurial universities. While the increasing university size has a negative effect on university entrepreneurial scores, the socio-economic development factor of the region positively contributes to the scores. Young universities are also found to benefit more from the large share of the graduate students of their student composition on university entrepreneurship and innovation scores. -

Mehmet HARMA Adress: Kadir Has University Dept

Mehmet HARMA Adress: Kadir Has University Dept. of Psychology, Kadir Has Cad., Cibali Fatih, 34083 Istanbul – Turkey E-Mail: [email protected] and [email protected] Web: https://corelabsite.wordpress.com/ Education 2008-2014 Social Psychology, Ph.D. (May, 2014) Middle East Technical University (METU), Turkey 2011-2012 Visiting Researcher, Human Development Department Cornell University, USA 2005-2008 Social Psychology, M.Sc. Middle East Technical University (METU), Turkey 2000-2004 Psychology, B.Sc. Mersin University, Turkey Professional 05/2018 – Associate Prof. in Kadir Has University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 10/2016 – 11/2017 Assistant Prof. in Kadir Has University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 07/2016 – 10/2016 Visiting Scholar, Kyoto University, Department of Psychology, Kyoto, Japan 07/2014 – 07/2016 Assistant Prof. in Istanbul Kemerburgaz University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 11/2012 – 07/2014 Senior researcher in Koc University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul, Turkey 8/2012 – 06/2014 Visiting lecturer, Dogus University, Istanbul 08/2011 – 08/2012 Visiting Researcher, Cornell University, Dept. of Human Development, Ithaca, NY, USA 12/2005 – 07/2011 Research Assistant, Relationship Research Lab, METU, Psychology Department, Ankara 01/2009 – 07/2011 Research Assistant, Safety Research Lab, METU, Psychology Department, Ankara 02/2010 – 07/2010 Teaching Assistant, METU Psychology Department, Advance d Design and Statistical Procedures in the Assessment of Psychological Change; Graduate Course 09/2009 – 01/2010 -

Boğaziçi University 31Th International Sports Fest

Boğaziçi University 31th International Sports Fest Boğaziçi University Sports Committee www.busportsfest.com www.sportscommittee.com [email protected] 0090 212 257 1081 İstanbul, TURKEY 5 CONTENT INTRODUCTION 3 GENERAL PRESENTATION 4 BRANCHES 5 SCHEDULE 6 REGISTRATION & FEES 7 ACCOMMADATION 8 TRANSPORTATION 8 2 LEGAL ASPECTS 9 PROMOTIONAL SPORTS BRANCHES 9 FORMER PARTICIPANTS 10 Dear University Sports Association, The Sports Committee of Boğaziçi University is very proud of inviting you to the 31st Sports Festival (named as “Sports Fest 2011”) which is going to be held between 12th and 15th of May 2011 in Istanbul, Turkey.* The Annual International Sports Festival has been a long-standing traditional feature of the life and culture at Boğaziçi University. This festival will offer you a competitive sports meeting and also an amazing opportunity to meet sportsmen from all countries and all social backgrounds. Under the watchful eye of professional referees invited from respective federations, matches in 14 different branches of sports will take place on our school grounds and sports fields also. Besides these various matches, we will provide you with free entrances to social occasions, parties, live concerts and trips which are organized by Sports Committee. Please consider this document as an invitation to join our tournament for this year. You will find extra information about registration procedures and general organization at our web site, http://www.busportsfest.com. You can also contact us via fax, mail or telephone. 3 We would like to see you among us this May in Istanbul. Your participation will not only make the events even more competitive but perhaps most importantly more fun and enjoyable. -

Digital Seige

DIGITAL SEIGE EDITORS Ece KARADOĞAN DORUK Istanbul University, Faculty of Communication, Istanbul, Turkey Seda MENGÜ Istanbul University, Faculty of Political Sciences, Istanbul, Turkey Ebru ULUSOY Farmingdale State College, New York, USA Published by Istanbul University Press Istanbul University Central Campus IUPress Office, 34452 Beyazıt/Fatih Istanbul - Turkey www.iupress.istanbul.edu.tr Digital Seige Editors: Ece Karadoğan Doruk, Seda Mengü, Ebru Ulusoy E-ISBN: 978-605-07-0764-9 DOI: 10.26650/B/SS07.2021.002 Istanbul University Publication No: 5281 Published Online in April, 2021 It is recommended that a reference to the DOI is included when citing this work. This work is published online under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ This work is copyrighted. Except for the Creative Commons version published online, the legal exceptions and the terms of the applicable license agreements shall be taken into account. ii EDITORS Prof. Dr. Ece Karadoğan Doruk Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. Seda Mengü Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ebru Ulusoy Farmingdale State College, New York, USA ADVISORY BOARD Prof. Dr. Celalettin Aktaş Istanbul Commerce University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. Füsun Alver Istanbul Commerce University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. M. Bilal Arık Aydin Adnan Menderes University, Aydin, Turkey Prof. Dr. Oya Şaki Aydın Istanbul Commerce University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. Aysel Aziz Istanbul Yeni Yüzyıl University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. Güven N. Büyükbaykal Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. N. Melda Cinman Marmara University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr.