Breeding Biology of the Platypus Final Submission Jthomas Phd Thesis 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-21 Strategic Plan

2018-2021 Strategic plan Zoos Victoria Fighting Extinction to secure a future rich in wildlife Conservation Reach Impact Minister for Energy, Kate Vinot, Chair, Zoos Victoria Dr Jenny Gray, CEO, Zoos Victoria Environment and Climate Change, the Hon. Lily D’Ambrosio “Our zoos foster care and “Now, more than ever before, our conservation by connecting commitment is unwaveringly strong “Native wildlife are unique and people with wildlife and our to ensure that “no Victorian terrestrial, precious – and it’s important that commercial activities allow us to vertebrate species will go extinct on Victorians get involved in conserving make meaningful investments our watch.” It’s a rare privilege to and caring for our wildlife. Our zoos to protect our most vulnerable work with such amazing people in our play a vital role in achieving this goal.” species and fight extinction.” joined mission to fight extinction.” Vision Mission As a world leading zoo-based As a world leading zoo-based conservation organisation, we conservation organisation we will will fight extinction to secure a fight wildlife extinction through: future rich in wildlife. • Innovative, scientifically • Strong commercial sound breeding and recovery approaches that secure our programs to support critically financial sustainability; and endangered species; • Profound zoo-based experiences • Amplifying our voice as a that connect people with wildlife trusted champion for wildlife and enrich our world. conservation; ANIMALS CONSERVATION 1 Ensure that our efforts to care for 1 Complete the implementation of and conserve wildlife are justified, Wildlife Conservation Masterplan 1.0. humane and effective. 2 Develop and implement Wildlife 2 Advance staff skills and capacity Conservation Masterplan 2.0. -

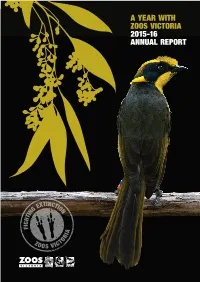

2015-16 ANNUAL REPORT Our Vision Is to Be the World’S Leading Zoo-Based Conservation Organisation

A YEAR WITH ZOOS VICTORIA 2015-16 ANNUAL REPORT Our vision is to be the world’s leading zoo-based conservation organisation. We do this by fighting wildlife extinction. Southern Corroboree Frog • Pseudophryne corroboree 2 ZOOS VICTORIA ANNUAL REPORT 2015–16 CONTENTS Chair’s Message 4 CEO’s Message 5 Our Charter and Purpose 6 Fighting Extinction 8 Animals of the Zoo 9 Highlights 2015-16 10 Five Action Areas Conservation 14 Our Animals 20 Visitors and Community 26 Our People 28 Financial Sustainability 30 Organisational Chart 32 Our Workplace Profile 33 Key Performance Indicators 34 Financial Summary 36 Board Attendance 37 Board Profiles 38 Board Committees 40 Corporate Governance and Other Disclosure 41 Our Partners and Supporters 45 Financial Report 49 ZOOS VICTORIA ANNUAL REPORT 2015–16 3 CHAIR’S MESSAGE “ We strive to profoundly influence people to take action to save wildlife.” Anne Ward, Chair Zoos Victoria More people than ever before are The Minute to Midnight Gala Ball was visiting our zoos, with record visitation one such occasion where we engaged at Melbourne Zoo, Healesville Sanctuary an audience not traditionally associated and Werribee Open Range Zoo in 2015-16. with the Zoo. The night showcased Zoos And while we continue to attract Victoria, both as a great place to visit more people through our gates, we and one that is committed to saving continue to change and develop to meet wildlife. the expectations of our visitors. 2015-16 On behalf of the Board, staff and was a year of exploration and reflection animals of Zoos Victoria, I would like at our zoos as we embarked on new to acknowledge the many people and ways to foster deeper connections organisations that have helped make between our visitors and our animals. -

Venomous Collections Kenneth D

Venomous collections Kenneth D. Winkel and Jacqueline Healy In many countries now, Stanley Cohen’s discovery of growth his work on anaphylaxis.3 Richet’s research in Universities is factors, and the 2003 chemistry work commenced with the study of under severe financial restraint. prize for Roderick MacKinnon’s the effects of jellyfish venom and led This is a short-sighted policy. structural and mechanistic studies to a new understanding of allergy. Ways have to be found to of ion channels.2 Moreover, venoms Although the scientific utility and maintain University research contributed, from ‘improbable societal fascination with venoms, untrammelled by requirements beginnings’ through ‘convoluted and venomous creatures, predates of forecasting application or pathways’, to early Nobel Prizes such the University of Melbourne, this usefulness. Those who wish to as Charles Richet’s 1913 physiology ancient theme finds expression study the sex-life of butterflies, or medicine prize in recognition of through many of its collections. or the activities associated with snake venom or seminal fluid should be encouraged to do so. It is such improbable beginnings that lead by convoluted pathways to new concepts and then, perhaps some 20 years later, to new types of drugs. —John R. Vane, 19821 More than 30 years after Nobel Prize-winner John Vane’s invocation concerning the value of curiosity- driven research, including allusion to the role snake venom played in his pathway to pharmacological discovery, this sentiment remains just as relevant. Indeed, at least two subsequent Nobel Prizes involved the use of venoms or toxins as key sources of bioactive compounds or critical molecular probes of structure-function relationships: the 1986 physiology or medicine prize for Rita Levi-Montalcini’s and Kenneth D. -

NEWSLETTER 2011 年 4 月 Vol. 3

NEWSLETTER 2011 年 4 月 Vol. 3 To Supporters of the AJWCEF Tetsuo Mizuno, Managing Director Thank you for your understanding of and cooperation towards the Australia-Japan Wildlife Conservation and Education Foundation. Looking back over the past year, in August the Foundation was fortunate to receive some funding for its activities from the Australian Commonwealth Government via a grant from the Australia Japan Foundation. We participated in our first international conference (the 10th Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, COP10) and, as a result, were able to register with the Head Office for the Convention on Biological Diversity, an organ of the United Nations. As part of our activities to educate about wildlife conservation, an important element of our work, at COP10 the Foundation presented research papers at a side event to the main conference, had a display booth and conducted a citizens’ forum to disseminate information more widely to the general public. We also visited several universities in Japan to present seminars on the current state of wildlife in Australia and their protection, etc. These were well attended, with close to 100 students gathering at some venues, and it was truly significant to be able to speak with the youth of the next generation. Currently we have two projects underway, one being the establishment of an international artificial insemination network and gene bank to maintain a healthy genetic diversity among the Australian animals that have been sent to zoos overseas. The other is eucalyptus plantations for the purpose of securing food for injured and sick wild koalas that have been hospitalized. -

Incursions/ Excursions

CMA Region Examples of Incursions/ Excursions (location) Marine and Freshwater Discovery Centre – Queenscliff Corangamite Narana Aboriginal Cultural Centre – Geelong Conservation Ecology Centre – Cape Otway Black Snake Company East Gippsland Fishcare Bug Blitz Meet the maremmas – penguin guard dogs tours at Warrnambool. Glenelg Hopkins Budj Bim tours of World Heritage listed National Heritage Landscapes at Lake Condah. Tour of Yatmerone Reserve through the Penshurst Volcanoes Discovery Centre. Winton Wetlands Euroa Arboretum Goulburn Broken Mansfield Zoo Shepparton Botanic Gardens Yea Wetlands Welcome to the Kyabram Fauna Park - Protecting Australia's Wildlife Heritage Mallee Environmental Education at the Mildura Eco Village Strathallan Landcare Group- Squirrel Glider Sanctuary Tours (Echuca area) North Central PepperGreen Farm (Bendigo Based) TZR Reptiles and Wildlife Incursions (Bendigo Based) Wild Action Zoo (Macedon based) North East SEED School Excursions & Educational Directory Friends of the Mitta Melbourne’s Living Museum of the West CERES Edithvale-Seaford Wetland Education Centre Ecolink Healesville Sanctuary Port Phillip & Mt Rothwell Western Port Phillip Island Nature Parks Port Phillip Eco Centre Marine and Freshwater Discovery Centre Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria- Melbourne and Cranbourne Serendip Sanctuary Waterwatch Bunurong Environment Centre, Inverloch West Gippsland Bass Coast’s Environmental Detectives Heart Morass with Bug Blitz Trust Little Desert Nature Lodge Wimmera Halls Gap Zoo Jamie & Kims Mobile Zoo Wildlife incursions 2021 Victorian Junior Landcare and Biodiversity Grants – Incursions/Excursions www.landcareaustralia.org.au/victorian-junior-landcare-biodiversity-grants 2021 Victorian Junior Landcare and Biodiversity Grants – Incursions/Excursions www.landcareaustralia.org.au/victorian-junior-landcare-biodiversity-grants . -

Emergency Response to Australia's Black Summer 2019–2020

animals Commentary Emergency Response to Australia’s Black Summer 2019–2020: The Role of a Zoo-Based Conservation Organisation in Wildlife Triage, Rescue, and Resilience for the Future Marissa L. Parrott 1,*, Leanne V. Wicker 1,2, Amanda Lamont 1, Chris Banks 1, Michelle Lang 3, Michael Lynch 4, Bonnie McMeekin 5, Kimberly A. Miller 2, Fiona Ryan 1, Katherine E. Selwood 1, Sally L. Sherwen 1 and Craig Whiteford 1 1 Wildlife Conservation and Science, Zoos Victoria, Parkville, VIC 3052, Australia; [email protected] (L.V.W.); [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (F.R.); [email protected] (K.E.S.); [email protected] (S.L.S.); [email protected] (C.W.) 2 Healesville Sanctuary, Badger Creek, VIC 3777, Australia; [email protected] 3 Marketing, Communications & Digital Strategy, Zoos Victoria, Parkville, VIC 3052, Australia; [email protected] 4 Melbourne Zoo, Parkville, VIC 3052, Australia; [email protected] 5 Werribee Open Range Zoo, Werribee, VIC 3030, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: In the summer of 2019–2020, a series of more than 15,000 bushfires raged across Citation: Parrott, M.L.; Wicker, L.V.; Australia in a catastrophic event called Australia’s Black Summer. An estimated 3 billion native Lamont, A.; Banks, C.; Lang, M.; animals, and whole ecosystems, were impacted by the bushfires, with many endangered species Lynch, M.; McMeekin, B.; Miller, K.A.; pushed closer to extinction. Zoos Victoria was part of a state-led bushfire response to assist wildlife, Ryan, F.; Selwood, K.E.; et al. -

Download the Annual Report 2019-2020

Leading � rec�very Annual Report 2019–2020 TARONGA ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 A SHARED FUTURE � WILDLIFE AND PE�PLE At Taronga we believe that together we can find a better and more sustainable way for wildlife and people to share this planet. Taronga recognises that the planet’s biodiversity and ecosystems are the life support systems for our own species' health and prosperity. At no time in history has this been more evident, with drought, bushfires, climate change, global pandemics, habitat destruction, ocean acidification and many other crises threatening natural systems and our own future. Whilst we cannot tackle these challenges alone, Taronga is acting now and working to save species, sustain robust ecosystems, provide experiences and create learning opportunities so that we act together. We believe that all of us have a responsibility to protect the world’s precious wildlife, not just for us in our lifetimes, but for generations into the future. Our Zoos create experiences that delight and inspire lasting connections between people and wildlife. We aim to create conservation advocates that value wildlife, speak up for nature and take action to help create a future where both people and wildlife thrive. Our conservation breeding programs for threatened and priority wildlife help a myriad of species, with our program for 11 Legacy Species representing an increased commitment to six Australian and five Sumatran species at risk of extinction. The Koala was added as an 11th Legacy Species in 2019, to reflect increasing threats to its survival. In the last 12 months alone, Taronga partnered with 28 organisations working on the front line of conservation across 17 countries. -

An Experimental Analysis of the Escape Response of the Gastropod

Pacific Science(1977), Vol. 31, No.1, p. 1-11 Printed in Great Britain An Experimental Analysis of the Escape Response of the Gastropod Strombus maculatus I LAURENCE H. FIELD 2 ABSTRACT: The escape response of Strombus maculatus is described in detail, including the apparent adaptive morphology of the foot, operculum, and eyestalks. The response is elicited by a chemical stimulus from two molluscivorous species of Conus and two gastropod-eating species of Cymatium but not from other pre datory species of these genera. Strombus habituated within three trials to a solution of "factor" from Conus pennaceus, but habituated only rarely, and then only after many trials, to contact with the live Conus. It was concluded that the eyes of S. maculatus are not used to see the Conus; however, eye removal significantly disrupted the orientation of the escape response, suggesting that the animal monitors some environmental cue such as polarized light. Tentacle removal appeared to interfere with escape response orientation but only to a variable extent. HERBIVOROUS GASTROPODS exhibit distinctive posterior end of the foot is thrust against the escape behavior from sea stars (Bauer 1913, substrate, causing the shell and head to lunge Feder and Christensen 1966) and predatory forward. Little additional work has been done gastropods (reviews by Kohn 1961, Robertson on strombid locomotion, and as Kohn and 1961, Kahn and Waters 1966, Gonor 1965, Waters (1966: 341) indicated, "the component 1966). 'Strombus has the remarkable ability to steps of the process have not been analyzed and escape from predators by rapid lunges, using the the functional morphology remains to be operculum to push against the substrate (Kohn studied in detail." Recently Berg (1972) and Waters 1966). -

FRESHWATER CRABS in AFRICA MICHAEL DOBSON Dr M

CORE FRESHWATER CRABS IN AFRICA 3 4 MICHAEL DOBSON FRESHWATER CRABS IN AFRICA In East Africa, each highland area supports endemic or restricted species (six in the Usambara Mountains of Tanzania and at least two in each of the brought to you by MICHAEL DOBSON other mountain ranges in the region), with relatively few more widespread species in the lowlands. Recent detailed genetic analysis in southern Africa Dr M. Dobson, Department of Environmental & Geographical Sciences, has shown a similar pattern, with a high diversity of geographically Manchester Metropolitan University, Chester St., restricted small-bodied species in the main mountain ranges and fewer Manchester, M1 5DG, UK. E-mail: [email protected] more widespread large-bodied species in the intervening lowlands. The mountain species occur in two widely separated clusters, in the Western Introduction Cape region and in the Drakensburg Mountains, but despite this are more FBA Journal System (Freshwater Biological Association) closely related to each other than to any of the lowland forms (Daniels et Freshwater crabs are a strangely neglected component of the world’s al. 2002b). These results imply that the generally small size of high altitude inland aquatic ecosystems. Despite their wide distribution throughout the species throughout Africa is not simply a convergent adaptation to the provided by tropical and warm temperate zones of the world, and their great diversity, habitat, but evidence of ancestral relationships. This conclusion is their role in the ecology of freshwaters is very poorly understood. This is supported by the recent genetic sequencing of a single individual from a nowhere more true than in Africa, where crabs occur in almost every mountain stream in Tanzania that showed it to be more closely related to freshwater system, yet even fundamentals such as their higher taxonomy mountain species than to riverine species in South Africa (S. -

Fighting Extinction Challenge Student Workbook Middle Years

Fighting Extinction Challenge Student Workbook Middle Years 5-8 Introduction The aim of this program is for you to: Examine a diverse range of animals and ecosystems Identify animal adaptations and classify animals using techniques to study animals in the field Identify the ecological relationships affecting the survival of a species Consider how human activities have affected the survival of a species Independently decide which local species you will advocate to conserve, through leadership back at school Learn about Wurundjeri culture and how they care for country Today’s challenge: ‘How will you help save endangered wildlife?’ The Healesville Sanctuary Learning Experiences Team respectfully acknowledges the Wurundjeri People as the Traditional Custodians of the Land on which we work, live and learn. We recognize their continuing connection to the land, water and wildlife and pay our respect to elders past, present and emerging. Endangered Species Species Endangered 2 Wurundjeri Investigation We can all be custodians of the land just as the Wurundjeri people have been for thousands of years. During your independent investigation around Healesville Sanctuary today look for ways that the Wurundjeri people lived on and cared for country. (Please record these observations in the box below). Look (tick what you saw) Hear (what you heard) I wonder…(questions to ask an expert or investigate back at school) Bunjil Waa Mindi Signs about plant uses Signs about animal dreaming stories Sculptures Scar Tree Bark Canoe Gunyah Information about Coranderrk William Barak sculpture Information about William Barak Artefacts (eg eel trap, marngrook, possum skin cloak) 3 Animal Classification and Structural Adaptations In order for us to understand how living organisms are related, they are arranged into different groups. -

Ecomorphology of Feeding in Coral Reef Fishes

Ecomorphology of Feeding in Coral Reef Fishes Peter C. Wainwright David R. Bellwood Center for Population Biology Centre for Coral Reef Biodiversity University of California at Davis School of Marine Biology and Aquaculture Davis, California 95616 James Cook University Townsville, Queensland 4811, Australia I. Introduction fish biology. We have attempted to identify generalities, II. How Does Morphology Influence Ecology? the major patterns that seem to cut across phylogenetic III. The Biomechanical Basis of Feeding Performance and geographic boundaries. We begin by constructing IV. Ecological Consequences of Functional a rationale for how functional morphology can be used Morphology to enhance our insight into some long-standing eco- V. Prospectus logical questions. We then review the fundamental me- chanical issues associated with feeding in fishes, and the basic design features of the head that are involved in prey capture and prey processing. This sets the stage I. Introduction for a discussion of how the mechanical properties of fish feeding systems have been modified during reef fish di- nce an observer gets past the stunning coloration, versification. With this background, we consider some O surely no feature inspires wonder in coral reef of the major conclusions that have been drawn from fishes so much as their morphological diversity. From studies of reef fish feeding ecomorphology. Because of large-mouthed groupers, to beaked parrotfish, barbeled space constraints we discuss only briefly the role of goatfish, long-snouted trumpet fish, snaggle-toothed sensory modalities--vision, olfaction, electroreception, tusk fish, tube-mouthed planktivores, and fat-lipped and hearingmbut these are also significant and diverse sweet lips, coral reef fishes display a dazzling array elements of the feeding arsenal of coral reef fishes and of feeding structures. -

Species Biological Report Neosho Mucket (Lampsilis Rafinesqueana)

Species Biological Report Neosho Mucket (Lampsilis rafinesqueana) Cover photo: Dr. Chris Barnhart (Missouri State University) Prepared by: The Neosho Mucket Recovery Team This species biological report informs the Draft Recovery Plan for the Neosho Mucket (Lampsilis rafinesqueana) (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2017). The Species Biological Report is a comprehensive biological status review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) for the Neosho Mucket and provides an account of species overall viability. A Recovery Implementation Strategy, which provides the expanded narrative for the recovery activities and the implementation schedule, is available at https://www.fws.gov/arkansas-es/. The Recovery Implementation Strategy and Species Biological Report are finalized separately from the Recovery Plan and will be updated on a routine basis. Executive Summary The Neosho Mucket is a freshwater mussel endemic to the Illinois, Neosho, and Verdigris River basins in Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma. It is associated with shallow riffles and runs comprising gravel substrate and moderate to swift currents, but prefers near-shore areas or areas out of the main current in Shoal Creek and Illinois River. It does not occur in reservoirs lacking riverine characteristics. The life-history traits and habitat requirements of the Neosho Mucket make it extremely susceptible to environmental change (e.g., droughts, sedimentation, chemical contaminants). Mechanisms leading to the decline of Neosho Mucket range from local (e.g., riparian clearing, chemical contaminants, etc.), to regional influences (e.g., altered flow regimes, channelization, etc.), to global climate change. The synergistic (interaction of two or more components) effects of threats are often complex in aquatic environments, making it difficult to predict changes in mussel and fish host(s) distribution, abundance, and habitat availability that may result from these effects.