Arcomb E M Ill S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formal Letter

Waters of Life Journey inside, outside, with ipse wilderness, on this gentle 4-day autumnal walking talking meander through the rich cultural history of the ancient Ouse valley in Sussex. Following the contours of the River Ouse, we will be invited to reflect on our life's journey; on the ancient flow which has sustained us, and the currents which run deep within our souls. As we stop to soak up the literary, artistic context of Charleston and Monk's House and the fascinating history of Lewes Castle and Museum, we will immerse ourselves in the riches of the landscape and our lives. Location: Sussex Ouse Valley Way; Newick to Southease, via Barcombe and Lewes, including visits to Charleston House and Monk’s House. Dates: Saturday 24th October 10:00am – Tuesday 27th October 17:00 2020. Difficulty: Nourishing; walking distance 21 miles, 4-7 miles per day, flat terrain, frequent stops, pace of 2mph. Accommodation: Shared rooms in B&B and hotel. Single supplement available on request. Cost: £400 per person. This includes all accommodation, entrance fees, transport & activities. Does not include meals, apart from breakfasts. Itinerary: Day 1: Newick to Barcombe Mills (6 miles). Meet at The Bull, Village Green, Newick. Packed lunch. Overnight at B&B in Barcombe. Pub supper. Evening circle time. Day 2: Barcombe Mills to Lewes (4 miles). Lunch at café in Lewes. Visit museum and castle. Free time. Overnight at hotel in Lewes. Supper at restaurant. Evening circle time. Day 3: Lewes to Charleston via Glynde (7 miles). Lunch at café at Charleston. Tour of house. -

Boating on Sussex Rivers

K1&A - Soo U n <zj r \ I A t 1" BOATING ON SUSSEX RIVERS NRA National Rivers Authority Southern Region Guardians of the Water Environment BOATING ON SUSSEX RIVERS Intro duction NRA The Sussex Rivers have a unique appeal, with their wide valleys giving spectacular views of Chalk Downs within sight and smell of the sea. There is no better way to enjoy their natural beauty and charm than by boat. A short voyage inland can reveal some of the most attractive and unspoilt scenery in the Country. The long tidal sections, created over the centuries by flashy Wealden Rivers carving through the soft coastal chalk, give public rights of navigation well into the heartland of Sussex. From Rye in the Eastern part of the County, small boats can navigate up the River Rother to Bodiam with its magnificent castle just 16 miles from the sea. On the River Arun, in an even shorter distance from Littlehampton Harbour, lies the historic city of Arundel in the heart of the Duke of Norfolk’s estate. But for those with more energetic tastes, Sussex rivers also have plenty to offer. Increased activity by canoeists, especially by Scouting and other youth organisations has led to the setting up of regular canoe races on the County’s rivers in recent years. CARING FOR OUR WATERWAYS The National Rivers Authority welcomes all river users and seeks their support in preserving the tranquillity and charm of the Sussex rivers. This booklet aims to help everyone to enjoy their leisure activities in safety and to foster good relations and a spirit of understanding between river users. -

BARCOMBE, SOUTHEASE. BARCOMBE Gives the Name to The

BARCOMBE, SOUTHEASE. 195 Windus, Beard, and Co. wine and spirit Wood, Mrs. Ann, gun, rifle, and pistol maker, merchants, St. Swithin's lane 194 High street Wingham, William, Lamb inn, Fisher st Wood, Mrs. Henry, baker, Mailing street Winch, Miss Elizabeth, milliner and dress Wood, William Robert, surgeon dentist, maker, 23 All Saints' 202 High street, and Carlisle house Winch, William, cooper and corn measure Pavilion buildings, Brighton maker, West street- Wood, William, baker and beer retailer, Wingbam, Henry, Crown hotel, High street Fisher street Wise William, music seller and boot maker, Station street BARCOMBE gives the name to the hundred, and is in the rape of Lewes. In 1851 there were 1075 inhabitants. The living is a rectory, in the -patronage of the Lord Chancellor, and incumbency of the Rev. R. Allen. The church is an ancient fabric, and the interior contains many monuments and brasses. The village is small, and situated about four mlles from Lewes ; when seen from the adjacent hiHs it has a pleasing effect. PosT OFFICE.-Gabriel Best, Postmaster. Letters are received through Lewes, which is the nearest office for Money Orders. Alien, Rev. R., M ..A.. Rector Richardson, Captain Thomas, Sutton Hurst Good, Mrs. Turner, Mrs. Mackay, Capt. Henry Fowler Austin, Henry, butcher Ho well, John, farmer Austin, William, -shoemaker Howell, Henry, farmer Best, Gabriel, grocer and draper Howell, John, Royal Oak Billiter, Richard Henry, miller, Barcombe Howell, Mrs. Sarah, farmer mills Kenward, George, farmer Briant, John, market gardener Knight, Thomas, farmer Budgen, Friend, farmer Martin, Mrs. farmer Burnett, James, wheelwright Martin, Mrs. Mary, miller Constable, John, builder and carpenter Norma~:~, Edward, blacksmith Cripps, James, shoemaker Peckham, J ames, farmer J<'eist, James, farmer Pumphrey, Thomas, market gardener Fielder, Stcphen, baker Reed, William, farmer Foster, Isaac, boys' school Roswell, Thomas, jun. -

Hamsey NEWS Summer 2021 EDITION

Hamsey NEWS Summer 2021 EDITION Cover photo by Andrew Miller www.hamsey.net High quality of work for all your Double Glazing and Carpentry needs at a fair price DOUBLE GLAZING CARPENTRY • Replacement of windows and doors in UPVC, • Hang doors, fit door liners, architrave, locks, aluminium and timber handles, skirting etc • Service and repairs to your existing double • Custom built in wardrobes/shelves, build flat glazed windows (e.g. replacement of old misted pack furniture etc glass units, broken handles, hinges & locks) • Stud walls, insulation board, plasterboard • Re-trim & seal old windows • Build garden sheds, summer houses, garden • Install UPVC Fascia, Soffit and Guttering - full decking etc replacement or cap over • Fit curtain poles and blinds • Install new or replace shiplap cladding in PVC or • Replace kitchen/bathroom silicone timber • Install new kitchen units/doors Ray All jobs considered - big or small Wicker Please contact Ray Wicker: DOUBLE GLAZING M: 07960 503 844 E: [email protected] RICHARD SOAN ROOFING SERVICES Flat & Pitched Roofing Quality Domestic • Heritage • Commercial • Education • Industrial Reputable for price, reliability and workmanship. All advice is free and Trades Undertaken: without obligation: - Slating & Tiling - Single Ply • Approved contractor - Reinforced - Liquid Coatings to numerous local Bituminous - Shingling authorities Membranes - Leadwork • Award winning projects - Mastic Asphalt - Green Roofs undertaken - - Telephone: 01273 486110 • Email: [email protected] • www.richardsoan.co.uk -

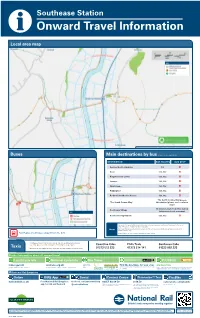

Main Destinations by Bus Local Area Map Buses Taxis

Southease Station i Onward Travel Information Local area map Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Buses Main destinations by bus (Data correct at April 2018) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP Denton/South Heighton 123 A Iford 123, 132 B Kingston-near-Lewes 123, 132 B Lewes 123, 132 B Newhaven 123, 132 A Piddinghoe 123, 132 A Rodmell (for Monk's House) 123, 132 B The South Downs Way passes 'The South Downs Way' this station (please see Local area map) 10 minutes walk from this station Southease Village (please see Local area map) Southover High Street 123, 132 B Bus route 123 operates Mondays to Saturdays only (most journeys continue in Newhaven to Denton as route 145, please contact Traveline for details). Notes Bus route 132 operates 1 journey to Lewes at 0951 and I journey to Newhaven at 1427 on Sundays & Public Holidays only. Rail Replacement buses depart from the A26. Direct trains operate to this destination from this station. Southease Station has no taxi rank or cab office. Advance booking is essential, please consider using the following local operators: Coastline Cabs Phils Taxis Seahaven Cabs Taxis (Inclusion of this number doesn’t represent any endorsement of the taxi firm) 01273 512 222 01273 514 141 01323 892 223 Further information about all onward travel www OnlineLocal Cycle Info www SustransNational Cycle Info Bus Times www PLUSBUS See timetable lewes.gov.uk sustrans.org.uk displays at bus Find the bus times for your stop. plusbus.info For more information about cycle routes. -

Kipling's Walk Leaflet

Others who have found inspiration roaming Notes on the walk ’ ’ the whale-backed Downs around South Downs Walks with more info at: www.kiplingfestivalrottingdean.co.uk Rottingean include writers Virginia Woolf, Katherine Mansfield, DH Lawrence, Oscar Bazehill Road 2 was the route Wilde, Enid Bagnold and Angela Thirkell, taken by the Kiplings in their pony cart ’ artists William and Ben Nicholson, Paul Nash, up to the motherly Downs for ’ Aubrey Beardsley and William Morris - while jam-smeared picnics . ROTTINGDEAN movie stars like Bette Davis, Errol Flynn, Cary The lost village of Balsdean 4 was Grant and Julie Andrews enjoyed stays at 800 years old when Canadian soldiers the Tudor Close Hotel. Following in their used it for target practice in WW2, footsteps with the wide sky above and the in the footsteps leaving little to see today except a pewter sea below may bring to mind , , plaque marking the chapel s altar. Kipling s personal tribute to the Downs: , of A Rifle Range at Lustrell s Vale 6 God gives all men all earth to love, Kipling was started during the Boer War by but, since man's heart is small, Kipling who was concerned about the ordains for each one spot shall prove lack of training and preparedness of beloved over all. and Company local youth. Each to his choice, and I rejoice Whiteway Lane 8 was once The lot has fallen to me the route for 17th and 18th century In a fair ground - in a fair ground - smugglers whisking their goods out of Yea, Sussex by the sea! , the village and inspiring Kiplin g s TRANSIT INFORMATION The Smuggle r,s Song: buses.co.uk nationalrail.co.uk Five and twenty ponies , Parking, W.C s, and refreshments in trotting through the dark, Rottingdean Village and on the seafront Brandy for the Parson, 'baccy for the Clerk. -

Here It Was Originally Found

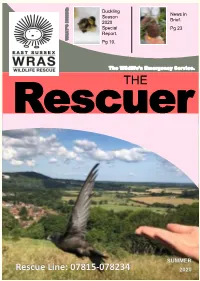

Duckling News in Season Brief: 2020 S INSIDE: S ’ Special Pg 23 Report. WHAT Pg 10. The Wildlife’s Emergency Service. RescuerTHE SUMMER Rescue Line: 07815-078234 2020 Content: Page 3 First Swift Release of the Year Happens at Lewes Page 5 Stuck Fox rescued in Eastbourne! Page 6 Tricky gull rescue on Eastbourne Beach. Page 7 Hedgehog Cake Winner! Page 8 Meet the Trustees Page 9 Volunteering during Covid-19. Page 10 & 11 Duckling Season 2020 - Special Report. Page 12 & 13 Four mums & ducklings rescues Uckfield. Page 14 Unusual Duckling Rescue Uckfield. Page 15 Haywards Heath Ducklings. Page 16 Sad outcome for Rail Deer Rescue. Page 17 A busy season so far! Page 18 Hedgehog falls in pot of glue. Page 19 Gull Season 2020. Page 20 Pigeon Post by Kathy Martyn Page 23 News in Brief Page 24 Contact Details. If you shop on Amazon, don’t forget to start shopping with Amazon Smile and select East Sussex WRAS as your chosen charity to help raise money free of charge for WRAS. Amazon Smile is now available as a mobile app too. Whats inside... Our first swift of the year was released back to the wild on Sunday 12th July with a further seven youngsters soon to follow. Members of WRAS’s Care Team took the first swift up onto the Downs above Lewes to release it back to the wild not far from where it was originally found. Swifts are very active at the moment in East Sussex and can often be seen swooping through the area gathering insects to feel their young. -

LOCUS FOCUS Forum of the Sussex Place-Names Net

ISSN 1366-6177 LOCUS FOCUS forum of the Sussex Place-Names Net Volume 2, number 1 • Spring 1998 Volume 2, number 1 Spring 1998 • NET MEMBERS John Bleach, 29 Leicester Road, Lewes BN7 1SU; telephone 01273 475340 -- OR Barbican House Bookshop, 169 High Street, Lewes BN7 1YE Richard Coates, School of Cognitive and Computing Sciences, University of Sussex, Brighton BN1 9QH; telephone 01273 678522 (678195); fax 01273 671320; email [email protected] Pam Combes, 37 Cluny Street, Lewes BN7 1LN; telephone 01273 483681; email [email protected] [This address will reach Pam.] Paul Cullen, 67 Wincheap, Canterbury CT1 3RX; telephone 01233 612093 Anne Drewery, The Drum, Boxes Lane, Danehill, Haywards Heath RH17 7JG; telephone 01825 740298 Mark Gardiner, Department of Archaeology, School of Geosciences, Queen’s University, Belfast BT7 1NN; telephone 01232 273448; fax 01232 321280; email [email protected] Ken Green, Wanescroft, Cambrai Avenue, Chichester PO19 2LB; email [email protected] or [email protected] Tim Hudson, West Sussex Record Office, County Hall, Chichester PO19 1RN; telephone 01243 533911; fax 01243 533959 Gwen Jones, 9 Cockcrow Wood, St Leonards TN37 7HW; telephone and fax 01424 753266 Michael J. Leppard, 20 St George’s Court, London Road, East Grinstead RH19 1QP; telephone 01342 322511 David Padgham, 118 Sedlescombe Road North, St Leonard’s on Sea TH37 7EN; telephone 01424 443752 Janet Pennington, Penfold Lodge, 17a High Street, Steyning, West Sussex BN44 3GG; telephone 01903 816344; fax 01903 879845 Diana -

NOTICE of POLL ELECTION of COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the CHAILEY DIVISION

EAST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL NOTICE OF POLL ELECTION OF COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the CHAILEY DIVISION 1. A poll for the election of 1 COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the above named DIVISION / COUNTY will be taken on THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 between the hours of 07:00 AM and 10:00 PM. 2. The names, in alphabetical order, of all PERSONS VALIDLY NOMINATED as candidates at the above election with their respective home addresses in full and descriptions, and the names of the persons who signed their nomination papers are as follows:- Names of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Names of Persons who have signed the Nomination Paper ATKINS 14 ST JAMES STREET, GREEN PARTY GILLIAN M LACEY MANDY J LEWIS LEWES VICTORIA E WHITEMAN HOLLY BN7 1HR SUSAN M FLEMING JOSEPHINE P PEACH TIMOTHY J HUGHES STEPHEN F BALDWIN JANE HUTCHINGS SUSANNA R STEER MARIE N COLLINS BELCHER NEALS FARM, LABOUR PARTY SIMON J PEARL COLIN B PERKINS EAST GRINSTEAD STEVIE J FREEMAN NICHOLAS ROAD, JAMES M FREEMAN GEORGE NORTH CHAILEY, SALLY D LANE LEWES FIONA M A PEARL RORY O'CONNOR BN8 4HX JOHANNA ME CHAMBERLAIN EDMUND R CHAMBERLAIN MICHELLE STONE GARDINER BROADLANDS, LIBERAL ROSALYN M ST PIERRE PAULINE R CRANFIELD LEWES ROAD, DEMOCRAT MARION J HUGHES PETER FREDERICK RINGMER JAMES I REDWOOD BN8 5ER CHARLOTTE J MITCHELL LESLEY A DUNFORD EMMA C BURNETT MICHAEL J CRUICKSHANK ALAN L D EVISON SARAH J OSBORNE SHEPPARD 1 POWELL ROAD, THE PETER D BURNIE CHRISTOPHER R GODDARD NEWICK, CONSERVATIVE MARY EL GODDARD JIM LEWES, PARTY CHRISTINE E RIPLEY EAST SUSSEX CANDIDATE NICHOLAS W BERRYMAN BN8 4LS SHEILA M BURNIE LOUIS RAMSEY JONATHAN E RAMSEY KIM L RAMSEY DAVID JM HUTCHINSON 3. -

Newhaven Transport Study Report

Newhaven Transport Study July 2011 Lewes District Council Newhaven290816 ITD Transport ITW 001 G P:\Southampton\ITW\Projects\290816\WP\Newhaven_transport_study_re port 260711 doc Study July 2011 July 2011 Lewes District Council 32 High Street, Lewes, East Sussex, BN7 2LX Mott MacDonald, Stoneham Place, Stoneham Lane, Southampton SO50 9NW, United Kingdom T +44(0) 23 8062 8800 F +44(0) 23 8062 8801, W www.mottmac.com Newhaven Transport Study Issue and revision record Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description A April 2011 N Gordon Draft B May 2011 N Gordon Draft – intro amended, sec 4.6 completed C June 2011 N Gordon I Johnston I Johnston Draft – Comments received 26/5/11 included D June 2011 N Gordon, L Dancer I Johnston I Johnston All sections completed E July 2011 N Gordon I Johnston I Johnston Scenario 1 mitigation added F July 2011 N Gordon I Johnston I Johnston Scenarios 4 and 5 added G July 2011 N Gordon I Johnston I Johnston Scenario 1 run with TEMPRO62 growth This document is issued for the party which commissioned it We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this and for specific purposes connected with the above-captioned document being relied upon by any other party, or being used project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which used for any other purpose. is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. -

Rural Settlement Distance and Sustainability Study

Rural Settlement Study: Sustainability; Distance Settlement Within 2 km walk (1¼ Miles) Within 3 km walk Within 5km drive FP indicates some footpath access on part of the route use of italics indicate settlements beyond the Lewes District boundary Barcombe Cross Barcombe FP Ringmer Barcombe Barcombe Cross FP Cooksbridge Offham Glynde Firle FP Beddingham Lewes Ringmer Chailey N Newick, Chailey Green South Street South Chailey Wivelsfield FP Wivelsfield Green FP Chailey S South Street, Chailey Green FP North Chailey Barcombe Cross FP Chailey Green (central) South Street FP South Chailey FP North Chailey Newick FP Ditchling Keymer FP Westmeston FP Streat FP Plumpton FP East Chiltington FP East Chiltington Plumpton Green FP Plumpton FP Ditchling FP Cooksbridge FP South Chailey FP South Street FP Falmer Kingston FP Brighton FP Lewes FP Firle Glynde FP Cooksbridge Hamsey FP Offham Barcombe FP Lewes Hamsey Cooksbridge FP Offham Lewes Iford Rodmell FP Kingston Lewes Kingston Iford FP Rodmell FP Lewes FP Southease FP Falmer FP Newick North Chailey Chailey Green FP South Street FP Uckfield FP Offham Hamsey Cooksbridge Plumpton Piddinghoe Newhaven Peacehaven Plumpton Westmeston East Chiltington FP Offham Plumpton Green FP Ringmer Broyle Side Upper Wellingham Lewes FP Glynde FP Barcombe Cross Barcombe FP Rodmell Southease Iford Southease Rodmell Iford South Street Chailey Green FP South Chailey FP East Chiltington FP North Chailey FP Cooksbridge FP Streat Plumpton Green FP Ditchling FP East Chiltington FP Plumpton FP Westmeston Tarring Neville South Heighton Denton Newhaven Southease FP Rodmell FP Seaford Telscombe Saltdean FP Peacehaven FP Piddinghoe FP Southese Rodmell Iford Piddinghoe Westmeston Ditchling FP Plumpton Wivelsfield Burgess Hill FP N Chailey FP Plumpton Green Wivelsfield Green Wivelsfield Burgess Hill Plumpton Green FP Haywards Heath N Chailey FP S Chailey FP Chailey Green FP . -

Artwave 2016

ARTWAVE 2016 20 August - 4 September ● www.artwavefestival.org RTWAVE continues to grow and expand across our beautiful district and surroundings every year, and with 123 different venues to visit, and almost 400 artists taking part, 2016 is no exception. The Artwave team are delighted to welcome back past artists Aand makers as well as introduce many new ones to the festival this year. Come and find some amazing, wonderful and unique work on show in a variety of venues, including a caravan, open studios and galleries; private homes, garages, cafes and gardens. Our popular trails are back again, and this year, include the Haven Trail in Peacehaven and Newhaven, three different Rural Trails and our town ones in Seaford and Lewes. For a preview of work, a selection of venues in Lewes are opening their doors on Friday 19 August between 6pm and 8pm for a private view. (p 12) There’s a great array of workshops and events happening too (p31), including alfresco life drawing, arts psychotherapy taster sessions, children’s scavenger hunts, book making, stone carving and even creating your own art masterpiece on a piece of cake. I’m delighted to support Artwave Festival, as it gives our local artists a great opportunity to showcase their talent, creativity and skills, and I plan to visit as many of them as I can. I’m also pleased to support two specific events, Artwave’s own Surrealist Art Café, raising money for Cancer Research, and the Artwave Favourite Artist Award, as voted by you. Be sure to place your vote as you might get to see their work on next year’s brochure (see p30).