Earth Science Chapter 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shaded Elevation Map of Ohio

STATE OF OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Ted Strickland, Governor Sean D. Logan, Director Lawrence H. Wickstrom, Chief SHADED ELEVATION MAP OF OHIO 0 10 20 30 40 miles 0 10 20 30 40 kilometers SCALE 1:2,000,000 427-500500-600600-700700-800800-900900-10001000-11001100-12001200-13001300-14001400-1500>1500 Land elevation in feet Lake Erie water depth in feet 0-6 7-12 13-18 19-24 25-30 31-36 37-42 43-48 49-54 55-60 61-66 67-84 SHADED ELEVATION MAP This map depicts the topographic relief of Ohio’s landscape using color lier impeded the southward-advancing glaciers, causing them to split into to represent elevation intervals. The colorized topography has been digi- two lobes, the Miami Lobe on the west and the Scioto Lobe on the east. tally shaded from the northwest slightly above the horizon to give the ap- Ridges of thick accumulations of glacial material, called moraines, drape pearance of a three-dimensional surface. The map is based on elevation around the outlier and are distinct features on the map. Some moraines in data from the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Elevation Dataset; the Ohio are more than 200 miles long. Two other glacial lobes, the Killbuck grid spacing for the data is 30 meters. Lake Erie water depths are derived and the Grand River Lobes, are present in the northern and northeastern from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data. This digi- portions of the state. tally derived map shows details of Ohio’s topography unlike any map of 4 Eastern Continental Divide—A continental drainage divide extends the past. -

Meyers Height 1

University of Connecticut DigitalCommons@UConn Peer-reviewed Articles 12-1-2004 What Does Height Really Mean? Part I: Introduction Thomas H. Meyer University of Connecticut, [email protected] Daniel R. Roman National Geodetic Survey David B. Zilkoski National Geodetic Survey Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/thmeyer_articles Recommended Citation Meyer, Thomas H.; Roman, Daniel R.; and Zilkoski, David B., "What Does Height Really Mean? Part I: Introduction" (2004). Peer- reviewed Articles. Paper 2. http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/thmeyer_articles/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UConn. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peer-reviewed Articles by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UConn. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Land Information Science What does height really mean? Part I: Introduction Thomas H. Meyer, Daniel R. Roman, David B. Zilkoski ABSTRACT: This is the first paper in a four-part series considering the fundamental question, “what does the word height really mean?” National Geodetic Survey (NGS) is embarking on a height mod- ernization program in which, in the future, it will not be necessary for NGS to create new or maintain old orthometric height benchmarks. In their stead, NGS will publish measured ellipsoid heights and computed Helmert orthometric heights for survey markers. Consequently, practicing surveyors will soon be confronted with coping with these changes and the differences between these types of height. Indeed, although “height’” is a commonly used word, an exact definition of it can be difficult to find. These articles will explore the various meanings of height as used in surveying and geodesy and pres- ent a precise definition that is based on the physics of gravitational potential, along with current best practices for using survey-grade GPS equipment for height measurement. -

Assignment: 14 Subject: - Social Science Class: - VI Teacher: - Mrs

Assignment: 14 Subject: - Social Science Class: - VI Teacher: - Mrs. Shilpa Grover Name: ______________ Class & Sec: _______________ Roll No. ______ Date: 23.05.2020 GEOGRAPHY QUESTIONS CHAPTER-2 A. Define the following terms: 1. Equator: It is an imaginary line drawn midway between the North and South Poles. It divides the Earth into two equal parts, the North Hemisphere and the South Hemisphere. 2. Earth’s grid: The network of parallels or latitudes and meridians or longitudes that divide the Earth’s surface into a grid-like pattern is called the Earth’s grid or geographic grid. 3. Heat zones: The Earth is divided into three heat zones based on the amount of heat each part receives from the Sun. These three heat zones are the Torrid Zone, the Temperate Zone and the Frigid Zone. 4. Great circle: The Equator is known as the great circle, as it is the largest circle that can be drawn on the globe. This is because the equatorial diameter of the Earth is the largest. 5. Prime Meridian: It is the longitude that passes through Greenwich, a place near London in the UK. It is treated as the reference point. Places to the east and west of the Prime Meridian are measured in degrees. 6. Time zones: A time zone is a narrow belt of the Earth’s surface, which has an east‒west extent of 15 degrees of longitude. The world has been divided into 24 standard time zones. B. Answer the following Questions: 1. What is the true shape of the Earth? The Earth looks spherical in shape, but it is slightly flattened at the North and South Poles and bulges at the equator due to the outward force caused by the rotation of the Earth. -

Why Do We Use Latitude and Longitude? What Is the Equator?

Where in the World? This lesson teaches the concepts of latitude and longitude with relation to the globe. Grades: 4, 5, 6 Disciplines: Geography, Math Before starting the activity, make sure each student has access to a globe or a world map that contains latitude and longitude lines. Why Do We Use Latitude and Longitude? The Earth is divided into degrees of longitude and latitude which helps us measure location and time using a single standard. When used together, longitude and latitude define a specific location through geographical coordinates. These coordinates are what the Global Position System or GPS uses to provide an accurate locational relay. Longitude and latitude lines measure the distance from the Earth's Equator or central axis - running east to west - and the Prime Meridian in Greenwich, England - running north to south. What Is the Equator? The Equator is an imaginary line that runs around the center of the Earth from east to west. It is perpindicular to the Prime Meridan, the 0 degree line running from north to south that passes through Greenwich, England. There are equal distances from the Equator to the north pole, and also from the Equator to the south pole. The line uniformly divides the northern and southern hemispheres of the planet. Because of how the sun is situated above the Equator - it is primarily overhead - locations close to the Equator generally have high temperatures year round. In addition, they experience close to 12 hours of sunlight a day. Then, during the Autumn and Spring Equinoxes the sun is exactly overhead which results in 12-hour days and 12-hour nights. -

Geographical Influences on Climate Teacher Guide

Geographical Influences on Climate Teacher Guide Lesson Overview: Students will compare the climatograms for different locations around the United States to observe patterns in temperature and precipitation. They will describe geographical features near those locations, and compare graphs to find patterns in the effect of mountains, oceans, elevation, latitude, etc. on temperature and precipitation. Then, students will research temperature and precipitation patterns at various locations around the world using the MY NASA DATA Live Access Server and other sources, and use the information to create their own climatogram. Expected time to complete lesson: One 45 minute period to compare given climatograms, one to two 45 minute periods to research another location and create their own climatogram. To lessen the time needed, you can provide students data rather than having them find it themselves (to focus on graphing and analysis), or give them the template to create a climatogram (to focus on the analysis and description), or give them the assignment for homework. See GPM Geographical Influences on Climate – Climatogram Template and Data for these options. Learning Objectives: - Students will brainstorm geographic features, consider how they might affect temperature and precipitation, and discuss the difference between weather and climate. - Students will examine data about a location and calculate averages to compare with other locations to determine the effect of geographic features on temperature and precipitation. - Students will research the climate patterns of a location and create a climatogram and description of what factors affect the climate at that location. National Standards: ESS2.D: Weather and climate are influenced by interactions involving sunlight, the ocean, the atmosphere, ice, landforms, and living things. -

Chapter Outline Thinking Ahead 4 EARTH, MOON, AND

Chapter 4 Earth, Moon, and Sky 103 4 EARTH, MOON, AND SKY Figure 4.1 Southern Summer. As captured with a fish-eye lens aboard the Atlantis Space Shuttle on December 9, 1993, Earth hangs above the Hubble Space Telescope as it is repaired. The reddish continent is Australia, its size and shape distorted by the special lens. Because the seasons in the Southern Hemisphere are opposite those in the Northern Hemisphere, it is summer in Australia on this December day. (credit: modification of work by NASA) Chapter Outline 4.1 Earth and Sky 4.2 The Seasons 4.3 Keeping Time 4.4 The Calendar 4.5 Phases and Motions of the Moon 4.6 Ocean Tides and the Moon 4.7 Eclipses of the Sun and Moon Thinking Ahead If Earth’s orbit is nearly a perfect circle (as we saw in earlier chapters), why is it hotter in summer and colder in winter in many places around the globe? And why are the seasons in Australia or Peru the opposite of those in the United States or Europe? The story is told that Galileo, as he left the Hall of the Inquisition following his retraction of the doctrine that Earth rotates and revolves about the Sun, said under his breath, “But nevertheless it moves.” Historians are not sure whether the story is true, but certainly Galileo knew that Earth was in motion, whatever church authorities said. It is the motions of Earth that produce the seasons and give us our measures of time and date. The Moon’s motions around us provide the concept of the month and the cycle of lunar phases. -

Reference Systems for Surveying and Mapping Lecture Notes

Delft University of Technology Reference Systems for Surveying and Mapping Lecture notes Hans van der Marel ii The front cover shows the NAP (Amsterdam Ordnance Datum) ”datum point” at the Stopera, Amsterdam (picture M.M.Minderhoud, Wikipedia/Michiel1972). H. van der Marel Lecture notes on Reference Systems for Surveying and Mapping: CTB3310 Surveying and Mapping CTB3425 Monitoring and Stability of Dikes and Embankments CIE4606 Geodesy and Remote Sensing CIE4614 Land Surveying and Civil Infrastructure February 2020 Publisher: Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences Delft University of Technology P.O. Box 5048 Stevinweg 1 2628 CN Delft The Netherlands Copyright ©20142020 by H. van der Marel The content in these lecture notes, except for material credited to third parties, is licensed under a Creative Commons AttributionsNonCommercialSharedAlike 4.0 International License (CC BYNCSA). Third party material is shared under its own license and attribution. The text has been type set using the MikTex 2.9 implementation of LATEX. Graphs and diagrams were produced, if not mentioned otherwise, with Matlab and Inkscape. Preface This reader on reference systems for surveying and mapping has been initially compiled for the course Surveying and Mapping (CTB3310) in the 3rd year of the BScprogram for Civil Engineering. The reader is aimed at students at the end of their BSc program or at the start of their MSc program, and is used in several courses at Delft University of Technology. With the advent of the Global Positioning System (GPS) technology in mobile (smart) phones and other navigational devices almost anyone, anywhere on Earth, and at any time, can determine a three–dimensional position accurate to a few meters. -

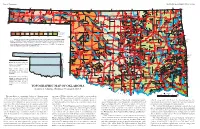

TOPOGRAPHIC MAP of OKLAHOMA Kenneth S

Page 2, Topographic EDUCATIONAL PUBLICATION 9: 2008 Contour lines (in feet) are generalized from U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps (scale, 1:250,000). Principal meridians and base lines (dotted black lines) are references for subdividing land into sections, townships, and ranges. Spot elevations ( feet) are given for select geographic features from detailed topographic maps (scale, 1:24,000). The geographic center of Oklahoma is just north of Oklahoma City. Dimensions of Oklahoma Distances: shown in miles (and kilometers), calculated by Myers and Vosburg (1964). Area: 69,919 square miles (181,090 square kilometers), or 44,748,000 acres (18,109,000 hectares). Geographic Center of Okla- homa: the point, just north of Oklahoma City, where you could “balance” the State, if it were completely flat (see topographic map). TOPOGRAPHIC MAP OF OKLAHOMA Kenneth S. Johnson, Oklahoma Geological Survey This map shows the topographic features of Oklahoma using tain ranges (Wichita, Arbuckle, and Ouachita) occur in southern contour lines, or lines of equal elevation above sea level. The high- Oklahoma, although mountainous and hilly areas exist in other parts est elevation (4,973 ft) in Oklahoma is on Black Mesa, in the north- of the State. The map on page 8 shows the geomorphic provinces The Ouachita (pronounced “Wa-she-tah”) Mountains in south- 2,568 ft, rising about 2,000 ft above the surrounding plains. The west corner of the Panhandle; the lowest elevation (287 ft) is where of Oklahoma and describes many of the geographic features men- eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas is a curved belt of forested largest mountainous area in the region is the Sans Bois Mountains, Little River flows into Arkansas, near the southeast corner of the tioned below. -

Datums in Texas NGS: Welcome to Geodesy

Datums in Texas NGS: Welcome to Geodesy Geodesy is the science of measuring and monitoring the size and shape of the Earth and the location of points on its surface. NOAA's National Geodetic Survey (NGS) is responsible for the development and maintenance of a national geodetic data system that is used for navigation, communication systems, and mapping and charting. ln this subject, you will find three sections devoted to learning about geodesy: an online tutorial, an educational roadmap to resources, and formal lesson plans. The Geodesy Tutorial is an overview of the history, essential elements, and modern methods of geodesy. The tutorial is content rich and easy to understand. lt is made up of 10 chapters or pages (plus a reference page) that can be read in sequence by clicking on the arrows at the top or bottom of each chapter page. The tutorial includes many illustrations and interactive graphics to visually enhance the text. The Roadmap to Resources complements the information in the tutorial. The roadmap directs you to specific geodetic data offered by NOS and NOAA. The Lesson Plans integrate information presented in the tutorial with data offerings from the roadmap. These lesson plans have been developed for students in grades 9-12 and focus on the importance of geodesy and its practical application, including what a datum is, how a datum of reference points may be used to describe a location, and how geodesy is used to measure movement in the Earth's crust from seismic activity. Members of a 1922 geodetic suruey expedition. Until recent advances in satellite technology, namely the creation of the Global Positioning Sysfem (GPS), geodetic surveying was an arduous fask besf suited to individuals with strong constitutions, and a sense of adventure. -

Educator Guide

E DUCATOR GUIDE This guide, and its contents, are Copyrighted and are the sole Intellectual Property of Science North. E DUCATOR GUIDE The Arctic has always been a place of mystery, myth and fascination. The Inuit and their predecessors adapted and thrived for thousands of years in what is arguably the harshest environment on earth. Today, the Arctic is the focus of intense research. Instead of seeking to conquer the north, scientist pioneers are searching for answers to some troubling questions about the impacts of human activities around the world on this fragile and largely uninhabited frontier. The giant screen film, Wonders of the Arctic, centers on our ongoing mission to explore and come to terms with the Arctic, and the compelling stories of our many forays into this captivating place will be interwoven to create a unifying message about the state of the Arctic today. Underlying all these tales is the crucial role that ice plays in the northern environment and the changes that are quickly overtaking the people and animals who have adapted to this land of ice and snow. This Education Guide to the Wonders of the Arctic film is a tool for educators to explore the many fascinating aspects of the Arctic. This guide provides background information on Arctic geography, wildlife and the ice, descriptions of participatory activities, as well as references and other resources. The guide may be used to prepare the students for the film, as a follow up to the viewing, or to simply stimulate exploration of themes not covered within the film. -

Coriolis Effect

Project ATMOSPHERE This guide is one of a series produced by Project ATMOSPHERE, an initiative of the American Meteorological Society. Project ATMOSPHERE has created and trained a network of resource agents who provide nationwide leadership in precollege atmospheric environment education. To support these agents in their teacher training, Project ATMOSPHERE develops and produces teacher’s guides and other educational materials. For further information, and additional background on the American Meteorological Society’s Education Program, please contact: American Meteorological Society Education Program 1200 New York Ave., NW, Ste. 500 Washington, DC 20005-3928 www.ametsoc.org/amsedu This material is based upon work initially supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. TPE-9340055. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2012 American Meteorological Society (Permission is hereby granted for the reproduction of materials contained in this publication for non-commercial use in schools on the condition their source is acknowledged.) 2 Foreword This guide has been prepared to introduce fundamental understandings about the guide topic. This guide is organized as follows: Introduction This is a narrative summary of background information to introduce the topic. Basic Understandings Basic understandings are statements of principles, concepts, and information. The basic understandings represent material to be mastered by the learner, and can be especially helpful in devising learning activities in writing learning objectives and test items. They are numbered so they can be keyed with activities, objectives and test items. Activities These are related investigations. -

THE EARTH. MERIDIANS and PARALLELS 2=Meridian (Geography)

THE EARTH. MERIDIANS AND PARALLELS 1=Circle of latitude 2=Meridian (geography) A circle of latitude , on the Earth , is an imaginary east -west circle connecting all locations (not taking into account elevation) that share a given latitude . A location's position along a circle of latitude is given by its longitude . Circles of latitude are often called parallels because they are parallel to each other. On some map projections, including the Equirectangular projection , they are drawn at equidistant intervals. Circles of latitude become smaller the farther they are from the equator and the closer they are to the poles . A circle of latitude is perpendicular to all meridians at the points of intersection, and is hence a special case of a loxodrome . Contrary to what might be assumed from their straight-line representation on some map projections, a circle of latitude is not, with the sole exception of the Equator, the shortest distance between two points lying on the Earth. In other words, circles of latitude (except for the Equator) are not great circles (see also great-circle distance ). It is for this reason that an airplane traveling between a European and North American city that share the same latitude will fly farther north, over Greenland for example. Arcs of circles of latitude are sometimes used as boundaries between countries or regions where distinctive natural borders are lacking (such as in deserts), or when an artificial border is drawn as a "line on a map", as happened in Korea . Longitude (λ) Lines of longitude appear vertical with varying curvature in this projection; but are actually halves of great ellipses, with identical radii at a given latitude.