The Natural Distribution of Eucalyptus Species in Tasmania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildtimes Edition 28

Issue 28 September 2006 75 years old and the Overland Track just gets better and better! The Overland Track is Australia’s most popular long-distance walk, with about 8,000 to 9,000 people making the trek each year. It’s a six- day walk travelling 65 kilometres through the heart of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area and it has earned an international reputation among bushwalkers. In recent years the growing popularity of the In this issue track has resulted in increased visitor numbers, leading to unsustainable environmental and – Celebrate 1997-2007 social pressures. Systematic monitoring by staff – New Editor and WILDCARE Inc volunteers noted increasing – New web site crowding at some campsites along the track, as The difference between previous years and this – KarstCARE Report well as overcrowding at huts, with as many 130 season (summer 2005/ 2006) was remarkable. people a night at one location. – Walking tracks in National Walkers, WILDCARE Inc volunteers and Parks Parks upgraded In June 2004, the vision for the Track was staff all enjoyed fewer crowds. While the total announced: The Overland Track will be – PWS Park Pass forms numbers of walkers using the track were similar Tasmania’s premier bushwalking experience. A to previous years, the difference was that the – Board Meetings key objective for management was to address flow of walkers was constant, rather than the – Group Reports the incidence of social crowding and to provide peaks and troughs of past seasons. – Tasmanian Devil Volunteers a quality experience for walkers. Volunteers have played a large part in the – David Reynolds - Volunteer Three key recommendations would drive the success of implementing the new arrangements Profile implementation of the vision: a booking system on the Overland Track. -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

Plant Communities of Mt Barrow & Mt Barrow Falls

PLANT COMMUNITIES OF MT BARROW & MT BARROW FALLS John B. Davies Margaret J. Davies Consultant Queen Victoria and Art and Plomley Foundation II Mt Barrow J.B. & M.J. (1990) of Mt Barrow and Mt Barrow No.2 © Queen Victoria and Art Wellington St., Launceston,Tasmania 1990 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 BACKGROUND 4 SURVEY MT BARROW 11 OF MT BARROW PLANT COMMUNITIES 14 AND THEIR RESERVATION COMPARISON THE VEGETATION AT 30 BARROW AND LOMOND BOTANICAL OF MT BARROW RESERVE 31 DESCRIPTION THE COMMUNITIES BARROW FALLS THEIR APPENDIX 1 36 APPENDIX 2 MAP 3 39 APPENDIX 4 APPENDIX 5 APPENDIX 6 SPECIES 49 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are due to a number of people for assistance with this project. Firstly administrative assistance was by the Director of the Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Mr Chris TasselL assistance was Michael Body, Kath Craig Reid and Mary Cameron. crt>''Y'it>,nt" are also due to Telecom for providing a key to the on the plateau, the Department of Lands, Parks and for providing a transparency base map of the area, and to Mr Mike Brouder and Mr John Harris Commission), for the use of 1 :20,000 colour aerial photographs of the area. Taxonomic was provided by Cameron (Honorary Research Associate, Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery) who also mounted all the plant collected, and various staff of the Tasmanian Herbarium particularly Mr Alex Dr Tony Orchard, Mr D. 1. Morris and Dr Winifred Curtis. thanks are due to Dr Brad Potts (Botany Department, of Tasmania) for assistance with data and table production and to Prof Kirkpatrick and Environmental ..J'U'U'~;'" of Tasmania) for the use and word-processing. -

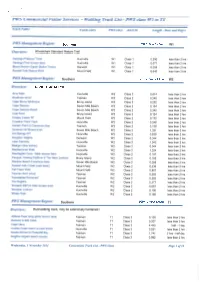

Walking Track List - PWS Class Wl to T4

PWS Commercial Visitor Services - Walking Track List - PWS class Wl to T4 Track Name FieldCentre PWS class AS2156 Length - Kms and Days PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: VV1 Overview: Wheelchair Standard Nature Trail Hastings Platypus Track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.290 less than 2 hrs Hastings Pool access track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.077 less than 2 hrs Mount Nelson Signal Station Tracks Derwent W1 Class 1 0.059 less than 2 hrs Russell Falls Nature Walk Mount Field W1 Class 1 0.649 less than 2 hrs PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: W2 Overview: Standard Nature Trail Arve Falls Huonville W2 Class 2 0.614 less than 2 hrs Blowhole circuit Tasman W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Cape Bruny lighthouse Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.252 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.154 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Beach Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.345 less than 2 hrs Coal Point Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.124 less than 2 hrs Creepy Crawly NT Mount Field W2 Class 2 0.175 less than 2 hrs Crowther Point Track Huonville W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Garden Point to Carnarvon Bay Tasman W2 Class 2 3.138 less than 2 hrs Gordons Hill fitness track Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 1.331 less than 2 hrs Hot Springs NT Huonville W2 Class 2 0.839 less than 2 hrs Kingston Heights Derwent W2 Class 2 0.344 less than 2 hrs Lake Osbome Huonville W2 Class 2 1.042 less than 2 hrs Maingon Bay lookout Tasman W2 Class 2 0.044 less than 2 hrs Needwonnee Walk Huonville W2 Class 2 1.324 less than 2 hrs Newdegate Cave - Main access -

Abcb - Annual Report - 19 - 1966-1967.Pdf

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA NINETEENTH ANNUAL REPORT AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CONTROL BOARD YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 1967 BY AUTHORITY A. J. ARTHUR, COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT PRINTER, CANBERRA: 1967 "' CONTENTS PAGE PAGE PART I: INTRODUCTORY 5 PART IV: BROADCASTING-PROGRAMME Legislation 5 SERVICES 38 Membership of the Board 6 Types of Programme 38 Functions of the Board 7 Composition of Programmes 39 Meetings of the Board . 7 Children's Programmes 40 Consultations with Licensees' Representa- News 40 tives and other Organisations 7 Religious Broadcasts 41 Staff of the Board 8 Political Broadcasts 42 State Organisation 9 Community Service 44 Location of Board's Offices 10 · Broadcasting of Telephone Conversations. 45 Broadcasts in Foreign Languages 46 Employment of Australians 46 Advertising 48 Medical Advertisements and Talks 49 PART II: BROADCASTING-ADMINISTRA- Broadcasting of Objectionable Matter 49 TION . 10 Programme Research 49 The Australian Broadcasting Services 10 Hours of Service 50 Licensing of Commercial Broadcasting Stations 10 PART V: TELEVISION- ADMINISTRATION 51 Current Licences for Commercial Broad- The Australian Television Serviees 51 casting Stations 10 Licensing of Commercial Television Stations 51 Grant of New Licences 11 Current Licences for Commercial Television Renewal of Licences 16 Stations 51 Fees for Licences for Commerical . Broad- Grant of New Licences 52 casting Stations 17 Renewal of Licences for Commercial Tele- Commercial Broadcasting Stations-Finan- vision Stations 52 .cial Results . 18 Fees for Licences for Commercial Television Transfer of Licences and Leasing of Stations 19 Stations 54 Ownership of Commercial Broadcasting Financial Results of Commercial Television Stations 19 Stations 55 Important Changes in Shareholdings in Ownership or Control of Commercial Broadcasting Stations 20 Television Stations 56 Organisations with Majority or Substantial Limitation of Interests in Commercial Tele- Interests in more than Two Commercial vision Stations 56 Broadcasting Stations 20 Important Changes in Shareholdings in Newspaper Companies . -

Verification of the Heritage Value of ENGO-Proposed Reserves

IVG REPORT 5A Verification of the heritage value of ENGO-proposed reserves Verification of the Heritage Value of ENGO-Proposed Reserves IVG Forest Conservation REPORT 5A 1 March 2012 IVG REPORT 5A Verification of the heritage value of ENGO-proposed reserves IVG Forest Conservation Report 5A Verification of the Heritage Value of ENGO-Proposed Reserves An assessment and verification of the ‘National and World Heritage Values and significance of Tasmania’s native forest estate with particular reference to the area of Tasmanian forest identified by ENGOs as being of High Conservation Value’ Written by Peter Hitchcock, for the Independent Verification Group for the Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement 2011. Published February 2012 Photo credits for chapter headings: All photographs by Rob Blakers With the exception of Chapter 2 (crayfish): Todd Walsh All photos copyright the photographers 2 IVG REPORT 5A Verification of the heritage value of ENGO-proposed reserves About the author—Peter Hitchcock AM The author’s career of more than 40 years has focused on natural resource management and conservation, specialising in protected areas and World Heritage. Briefly, the author: trained and graduated—in forest science progressing to operational forest mapping, timber resource assessment, management planning and supervision of field operations applied conservation—progressed into natural heritage conservation including conservation planning and protected area design corporate management—held a range of positions, including as, Deputy Director -

Terrestrial and Marine Protected Areas in Australia

TERRESTRIAL AND MARINE PROTECTED AREAS IN AUSTRALIA 2002 SUMMARY STATISTICS FROM THE COLLABORATIVE AUSTRALIAN PROTECTED AREAS DATABASE (CAPAD) Department of the Environment and Heritage, 2003 Published by: Department of the Environment and Heritage, Canberra. Citation: Environment Australia, 2003. Terrestrial and Marine Protected Areas in Australia: 2002 Summary Statistics from the Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database (CAPAD), The Department of Environment and Heritage, Canberra. This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Assistant Secretary Parks Australia South Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601. The views and opinions expressed in this document are not necessarily those of the Commonwealth of Australia, the Minister for Environment and Heritage, or the Director of National Parks. Copies of this publication are available from: National Reserve System National Reserve System Section Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 or online at http://www.deh.gov.au/parks/nrs/capad/index.html For further information: Phone: (02) 6274 1111 Acknowledgments: The editors would like to thank all those officers from State, Territory and Commonwealth agencies who assisted to help compile and action our requests for information and help. This assistance is highly appreciated and without it and the cooperation and help of policy, program and GIS staff from all agencies this publication would not have been possible. An additional huge thank you to Jason Passioura (ERIN, Department of the Environment and Heritage) for his assistance through the whole compilation process. -

Appendix 7-2 Protected Matters Search Tool (PMST) Report for the Risk EMBA

Environment plan Appendix 7-2 Protected matters search tool (PMST) report for the Risk EMBA Stromlo-1 exploration drilling program Equinor Australia B.V. Level 15 123 St Georges Terrace PERTH WA 6000 Australia February 2019 www.equinor.com.au EPBC Act Protected Matters Report This report provides general guidance on matters of national environmental significance and other matters protected by the EPBC Act in the area you have selected. Information on the coverage of this report and qualifications on data supporting this report are contained in the caveat at the end of the report. Information is available about Environment Assessments and the EPBC Act including significance guidelines, forms and application process details. Report created: 13/09/18 14:02:20 Summary Details Matters of NES Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act Extra Information Caveat Acknowledgements This map may contain data which are ©Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia), ©PSMA 2010 Coordinates Buffer: 1.0Km Summary Matters of National Environmental Significance This part of the report summarises the matters of national environmental significance that may occur in, or may relate to, the area you nominated. Further information is available in the detail part of the report, which can be accessed by scrolling or following the links below. If you are proposing to undertake an activity that may have a significant impact on one or more matters of national environmental significance then you should consider the Administrative Guidelines on Significance. World Heritage Properties: 11 National Heritage Places: 13 Wetlands of International Importance: 13 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park: None Commonwealth Marine Area: 2 Listed Threatened Ecological Communities: 14 Listed Threatened Species: 311 Listed Migratory Species: 97 Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act This part of the report summarises other matters protected under the Act that may relate to the area you nominated. -

M .. T-4. T N Bl{ Ttn'

M .. t-4.t N Bl{ttN' - -!i�Jt<�i.L-'- ANNUAL REPORT AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL 1978-79 '/ Annual Report Australian Broadcasting Tribunal 1978-79 Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra 1979 © Commonwealth of Australia 1979 Printed by The Courier-Mail Printing Service, Campbell Street, Bowen Hills, Q. 4006. The Honourable the Minister for Post and Telecommunications In conformity with the provisions of section 28 of the Broadcasting and Television Act 1942, I have pleasure in presenting the Annual Report of the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal forthe period 1 July 1978 to 30 June 1979. Bruce Gyngell Chairman 17 September 1979 Ill CONTENTS PART/ INTRODUCTION Page Legislation 1 Membership of the Tribunal 1 Functions of the Tribunal 2 Meetings of the Tribunal 2 Staff of the Tribunal 2 Overseas Visits 3 Addresses given by Tribunal Members and Staff 3 Location of Tribunal's Offices 4 Financial Accounts of the Tribunal 5 PART II. GENERAL Broadcasting and Television Services in operation since 1949 6 Financial Results - Commercial Broadcasting and Television Stations 7 Fees for Licences for Commercial Broadcasting and Television 9 Stations Broadcasting and Televising of Political Matter 12 Complaints from Viewers and Listeners about Programs 15 Children's Program Committee 18 Implementation of the Recommendations of the Self-Regulation 19 Report Senate Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs - 20 Freedom of Information PART III PUBLIC INQUIRIES Introduction 21 Legislation 21 Procedures forInquiries 21 Outline of -

Land Capability Survey of Tasmania

PIPERS REPORT LAND CAPABILITY SURVEY OF TASMANIA K E NOBLE 1990 PIPERS REPORT and accompanying 1:100 000 scale map Published by Department of Primary Industry, Tasmania with Published by the Department of Primary Industry, Tasmania. SBN © Copyright 1991 ISSN 1036-5249 Printed by Tasmanian Government Printing Office, Hobart Refer to this report as: Noble K. E. 1990, Land Capability Survey of Tasmania. Pipers Report. Department of Primary Industry, Tasmania, Australia. Accompanies 1:100 000 scale map, titled 'Land Capability Survey of Tasmania. Pipers' by K. E. Noble, Department of Primary Industry, Tasmania. 1990. CONTENTS PAGE 1 Introduction 5 2 Summary 6 3 Acknowledgements 7 4 How to use this Map and Report 8 5 Methodology 10 6 Land Capability Classification 11 7 Features of the Tasmanian Land Capability 13 Classification System 8 Land Capability Classes 17 9 Description of Area Mapped 22 10 Description of Land Capability Classes 34 on Pipers Map 11 Map Availability 56 1. Introduction The Department of Primary Industry in 1989 commenced a Land Capability Survey of Tasmania at a scale of 1:100 000. The primary aim of the survey is to identify and map the location and extent of different classes of agricultural land, in order to provide an effective base for land use planning decisions. In addition, the aim is to ensure that the long-term productivity of the land is maintained, through the promotion of compatible land uses and management practices. A land capability classification system has been developed specifically for Tasmania comprising seven classes, and is based on the capability of the land to support a range of agricultural uses on a long-term sustainable basis. -

A Compilation of Place Names and Their Histories in Tasmania

LA TROBE: Renamed Latrobe. LACHLAN: A small farming district 6 Km. south of New Norfolk. It is on the Lachlan Road, which runs beside a river of the same name. Sir John Franklin, in 1837, founded the settlement, and used the christian name of Governor Macquarie for the township. LACKRANA: A small rural settlement on Flinders Island. It is 10 Km. due east of Whitemark, over the Darling Range. A district noted for its dairy produce, it is also the centre of the Lackrana Wildlife Sanctuary. LADY BARRON: The main southern town on Flinders Island, 24 Km. south ofWhitemark. Situated in Adelaide Bay, it was named in honour of the wife of a Governor of Tasmania Sir Harry Barron. Places with names, which are very similar often, created confusion. LADY BAY: A small bay on the southern end of DEntrecasteaux Channel, 6 Km. east of Southport. It is almost deserted now except for a few holiday shacks. It was once an important port for the timber industry but there is very little of the wharf today. It has also been known as Lady's Bay. LADY NELSON CREEK: A small creek on the southern side of Dilston, it joins with Coldwater Creek and becomes a tributary of the Tamar River. The creek rises inland, near Underwood, and flows through some good farming country. It was an important freshwater supply in the early days of the colony. LAGOONS: An alternative name for Chain of Lagoons. It is 17 Km. south ofSt.Marys on the Tasman Highway. A geographical description of the inlet, which is named Saltwater Inlet, when the tide goes out it, leaves a "chain of lagoons". -

Picturesque Atlas of Australasia Maps

A-Signal Battery. I-Workshops. B-Observatory . K-Government House. C-Hospital. L-Palmer's Farm. .__4 S URVEY D-Prison. M-Officers ' Quarters. of E-Barracks . N-Magazine. F-Store Houses. 0-Gallows. THE SET TLEMENT ;n i Vh u/ ,S OUTN ALES G-Marine Barracks . P-Brick-kilns. H-Prisoners ' Huts. Q-Brickfields. LW OLLANI) iz /` 5Mile t4 2 d2 36 Engraved by A.Dulon 4 L.Poates • 1FTTh T i1111Tm»iTIT1 149 .Bogga 1 a 151 Bengalla • . l v' r-- Cootamundra Coola i r A aloe a 11lichellago 4 I A.J. SCALLY DEL. , it 153 'Greggreg ll tai III IJL. INDEX TO GENERAL MAP OF NE W SOUTH W ALES . NOTE -The letters after the names correspond with those in the borders of the map, and indicate the square in which the name will be found. Abercrombie River . Billagoe Mountain Bundella . J d Conjurong Lake . Dromedary Mountain. Aberdeen . Binalong . Bunda Lake C d Coogee . Drummond Mountain. Aberfoyle River . Binda . Bundarra . L c Cook (county) . Dry Bogan (creek) Acacia Creek . Bingera . Bunganbil Hill G g Coolabah . Dry Lake . Acres Billabong . Binyah . Bungarry Lake . E g Coolaburrag u ndy River Dry Lake Adelong Bird Island Bungendore J h Coolac Dry Lake Beds . Adelong Middle . Birie River Bungle Gully I c Coolah . Dry River . Ailsa . Bishop 's Bridge . Bungonia . J g Coolaman . Dubbo Creek Albemarle Black Head Bunker 's Creek . D d Coolbaggie Creek Dubbo Albert Lake . Blackheath Bunna Bunna Creek J b Cooleba Creek Duck Creek Albury . Black Point Bunyan J i Cooma Dudanman Hill . Alice Black Swamp Burbar Creek G b Coomba Lake Dudley (county) .