Topography and Settlement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prestbury Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan

DRAFT Prestbury Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan Cheltenham Borough Council Planning Policy Team Local Plan Draft Document May 2017 The Prestbury Conservation Area Appraisal is a draft document and will not come into force until the consultation stage is completed and they have been adopted by Chel- tenham Borough Council. Any suggested boundary change will not take place until that time. For any comments please contact [email protected] For more information on the existing Conservation Area Apprisails please click here. Swindon Village Prestbury Pitville Springbank Hester’s St Way Peter’s Whaddon Fiddler’s Green Oakley Fairview St Mark’s Lansdown Battledown The Reddings Bournside Hatherley The Park Charlton Park Charlton Kings Leckhampton Prestbury Conservation Area Conservation Areas (c) Crown copyright and database rights 2016 Ordanance Survey 10024384 Map 1. The location of Prestbury Conservation Area and other conservation areas in Cheltenham Prestbury Conservation Area Appraisal- Contents Contents 1.0 Introduction 01 6.0 Assessment of Condition 24 1.1 What is a Conservation Area? 01 6.1 General Condition 24 1.2 What is a Conservation Area Ap- 01 6.2 Key Threats 24 praisal and Management Plan? 6.3 Threats to Buildings 25 Implications of Conservation Area 1.3 01 6.4 Threats to Streetscape 25 Designation 1.4 Community Involvement 01 1.5 Dates of survey, adoption and pub- 01 lication 1.6 Proposed extensions 01 1.7 Statement of Special Character 02 Part 1: Appraisal 2.0 Context 05 2.1 Location and Setting -

Cambridgeshire County League Premier Division CAMBS-P

Cambridgeshire County League Premier Division CAMBS-P Chatteris Town West Street, Chatteris PE16 6HW CAMBS-P Cottenham United Cottenham Recreation Ground, King George V Playing Field, Lambs Lane, Cottenham CB24 8TB CAMBS-P Eaton Socon River Road, Eaton Socon PE19 3AU CAMBS-P Ely City reserves Unwin Ground, Downham Road, Ely CB6 1SH CAMBS-P Foxton Foxton Recreation Ground, Hardham Road, off High Street, Foxton CB22 6RP CAMBS-P Fulbourn Institute Fulbourn Recreation Grounds, Home End, Fulbourn CB21 5HS CAMBS-P Great Shelford Great Shelford Recreation Ground, Woollards Lane, Great Shelford CB22 5LZ CAMBS-P Hardwick Caldecote Recreation Ground, Furlong Way, Caldecote CB23 7ZA CAMBS-P Histon "A" Histon & Impington Recreation Ground, Bridge Road, Histon CB24 9LU Resigned CAMBS-P Hundon Hundon Recreation Ground, Upper North Street, Hundon CB10 8EE CAMBS-P Lakenheath The Pit, Wings Road, Lakenheath IP27 9HN CAMBS-P Littleport Town Littleport Sports & Leisure Centre, Camel Road, Littleport CB6 1PU CAMBS-P Newmarket Town reserves Newmarket Town Ground, Cricket Field Road, Newmarket CB6 8NG CAMBS-P Over Sports Over Recreation Ground, The Dole, Over CB24 5NW CAMBS-P Somersham Town West End Ground, St Ives Road, Somersham PE27 3EN CAMBS-P Waterbeach Waterbeach Recreation Ground, Cambridge Road, Waterbeach CB25 9NJ CAMBS-P West Wratting West Wratting Recreation Ground, Bull Lane, West Wratting CB21 5NP CAMBS-P Whittlesford United The Lawn, Whittlesford CB22 4NG Cambridgeshire County League Senior Division "A" CAMBS-SA Brampton Brampton Memorial Playing -

A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

A bus time schedule & line map A Benhall View In Website Mode The A bus line (Benhall) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Benhall: 6:33 AM - 6:33 PM (2) Cheltenham: 6:01 PM - 6:21 PM (3) Cheltenham: 6:22 AM - 10:50 PM (4) Hester's Way: 5:37 PM - 11:13 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next A bus arriving. Direction: Benhall A bus Time Schedule 38 stops Benhall Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:33 AM - 6:33 PM Cemetery, Cheltenham Tuesday 6:33 AM - 6:33 PM Whitethorn Drive, Prestbury Wednesday 6:33 AM - 6:33 PM Chiltern Road, Prestbury Thursday 6:33 AM - 6:33 PM Women's Institute Hall, Prestbury Friday 6:33 AM - 6:33 PM B4632, Cheltenham Saturday Not Operational Priors Road Junction, Prestbury Prescott Walk, Prestbury Chiltern Road, Prestbury A bus Info Direction: Benhall Cotswold Road, Prestbury Stops: 38 Trip Duration: 47 min Lynworth Exchange, Prestbury Line Summary: Cemetery, Cheltenham, Whitethorn Drive, Prestbury, Chiltern Road, Prestbury, Women's Institute Hall, Prestbury, Priors Road Junction, Cromwell Road, Cheltenham Prestbury, Prescott Walk, Prestbury, Chiltern Road, Prestbury, Cotswold Road, Prestbury, Lynworth Bouncer's Lane, Whaddon Exchange, Prestbury, Cromwell Road, Cheltenham, Bouncer's Lane, Whaddon, Community Centre, Community Centre, Whaddon Whaddon, Mersey Road, Whaddon, The Cat And Fiddle, Whaddon, Whaddon Drive, Whaddon, Mersey Road, Whaddon Whaddon Road, Cheltenham, Malden Road, Evenlode Avenue, -

Land at Leckhampton Leckhampton Gloucestershire Archaeological

Land at Leckhampton Leckhampton Gloucestershire Archaeological Evaluation for RPS Planning and Development CA Project: 3581 CA Report: 11301 January 2012 Land at Leckhampton Leckhampton Gloucestershire Archaeological Evaluation CA Project: 3581 CA Report: 11301 prepared by Stuart Joyce date 31 January 2012 checked by Cliff Bateman, Project Manager date 31 January 2012 approved by Simon Cox, Head of Fieldwork signed date 31 January 2012 issue 01 This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology Building 11, Kemble Enterprise Park, Kemble, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, GL7 6BQ t. 01285 771022 f. 01285 771033 e. [email protected] © Cotswold Archaeology Land at Leckhampton, Gloucestershire: Archaeological Evaluation CONTENTS SUMMARY........................................................................................................................ 2 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 3 2. RESULTS (FIGS 2-7) .......................................................................................... 5 3. DISCUSSION....................................................................................................... 15 4. CA PROJECT TEAM .......................................................................................... -

Folktalk Issue 58

Issue 58 FOLKtalk Autumn 2018 Friends of Leckhampton Hill & Charlton Kings Common Conserving and improving the Hill for you Inside this issue: FOLK AGM 2 The Word from Wayne 13 Walter Ballinger: Stalwart and soldier 3 Who painted the trig point? 16 Cheltenham remembers 4 Aerial photos 17 The flora and fauna on the Hill 5 Smoke Signals 17 Work party report 10 STALWARTS REMEMBERED AT THE WHEATSHEAF On Sunday September 30th, in bright sunshine with a hint of an autumn breeze, a plaque to commemorate the so called Leckhampton Stalwarts was unveiled by Neela Mann at The Wheatsheaf in Old Bath Road. A gathering of more than 50 people heard Neela, a local history expert and a FOLK member, pay tribute to Walter Ballinger and the other Stalwarts, who were imprisoned in 1906 as a result of their action to secure public access to the Hill. The Wheatsheaf was the headquarters for the Stalwarts and so it is fitting that the new plaque will be a permanent reminder of the sacrifice they made so that future generations could continue to enjoy the Hill. The Leckhampton Local History Society organised the event with their members being half of the gathering. FOLK was well represented. Martin Horwood, Leckhampton ward Borough Councillor and a supporter of FOLK was present. The current owner of the Dale Forty Piano company, Colin Crawford attended the unveiling. Colin is not related to Henry Dale, who bought the site in 1894 and was a protagonist in the drama, but he has an interest in the history. Walkers along the Cotswold Way from Hartley Lane will be able to see another plaque dedicated to a Stalwart and more information on the battle for access is available on the FOLK website www.leckhamptonhill.org.uk/site- description/history. -

Communications Roads Cheltenham Lies on Routes Connecting the Upper Severn Vale with the Cotswolds to the East and Midlands to the North

DRAFT – VCH Gloucestershire 15 [Cheltenham] Communications Roads Cheltenham lies on routes connecting the upper Severn Vale with the Cotswolds to the east and Midlands to the north. Several major ancient routes passed nearby, including the Fosse Way, White Way and Salt Way, and the town was linked into this important network of roads by more local, minor routes. Cheltenham may have been joined to the Salt Way running from Droitwich to Lechlade1 by Saleweistrete,2 or by the old coach road to London, the Cheltenham end of which was known as Greenway Lane;3 the White Way running north from Cirencester passed through Sandford.4 The medieval settlement of Cheltenham was largely ranged along a single high street running south-east and north-west, with its church and manorial complex adjacent to the south, and burgage plots (some still traceable in modern boundaries) running back from both frontages.5 Documents produced in the course of administering the liberty of Cheltenham refer to the via regis, the king’s highway, which is likely to be a reference to this public road running through the liberty. 6 Other forms include ‘the royal way at Herstret’ and ‘the royal way in the way of Cheltenham’ (in via de Cheltenham). Infringements recorded upon the via regis included digging and ploughing, obstruction with timbers and dungheaps, the growth of trees and building of houses.7 The most important local roads were those running from Cheltenham to Gloucester, and Cheltenham to Winchcombe, where the liberty administrators were frequently engaged in defending their lords’ rights. Leland described the roads around Cheltenham, Gloucester and Tewkesbury as ‘subject to al sodeyne risings of Syverne, so that aftar reignes it is very foule to 1 W.S. -

Community Connexions 278 Tetbury-Shipton Moyne

OPERATOR SERVICE ROUTE DAYS OF OPERATION COST PER YEAR The Villager Community Bus Services Ltd V2, V6, V22 Oddington - Stow - Bledington - Chipping Norton - Broadwell - Kingham - Swells - Icomb - Condicote Tues, Wed, Thur £8,000.00 Hedgehog North Cotswold Community Bus Association H3 H5 H7 Chipping Campden -Stratford- Mickleton-Evesham-Moreton in Marsh Tuesday - Friday £8,000.00 Pulham & Sons (Coaches) Ltd 802 Bourton-on-the-Water - The Rissingtons - Stow-On-The-Wold - Kingham Station Monday - Saturday £142,500.00 Pulham & Sons (Coaches) Ltd 855 Bourton-on-the-Water-Northleach-Bibury-Cirencester-Fairford Monday - Saturday £116,000.00 Pulham & Sons (Coaches) Ltd 606 Chipping Campden - Winchcombe - Cheltenham Monday - Saturday £177,685.00 Stagecoach West 50 76 77 78 50: Cirencester- Hospital-Mulberry Court - The Beeches- Ampney Crucis; 76/77: Highworth-Lechlade- Fairford- Cirencester; 78: Winson-Yanworth- Chedworth -Woodmancote -Cirencester Monday - Saturday £164,000.00 Pulham & Sons (Coaches) Ltd 803 Bourton-on-the-Water - Moreton-in-Marsh Tuesday £6,850.00 Pulham & Sons (Coaches) Ltd 804 Temple Guiting - Andoversford Tuesday £7,260.00 Pulham & Sons (Coaches) Ltd 832 Andoversford - Cold Aston Wednesday £7,350.00 Pulham & Sons (Coaches) Ltd 608 Cheltenham - Chipping Campden - Cheltenham Thursday £6,490.00 Stagecoach West B Charton Kings - Cheltenham Monday - Saturday (Evening) £21,800.00 Stagecoach West B CharltonKings - Cheltenham Sundays £19,500.00 Stagecoach West D Hatherley-Cheltenham Monday - Saturday (Evening) £24,100.00 Stagecoach -

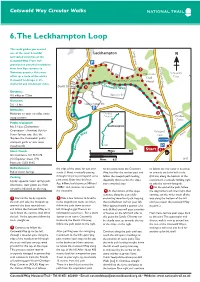

The Leckhampton Loop

Cotswold Way Circular Walks 6. The Leckhampton Loop This walk guides you around Sandy Lane one of the most beautiful Leckhampton N and varied stretches of the Cheltenham Road Cotswold Way. From rich grassland to peaceful woodlands, Cirencester Road from Iron Age remains to 5 Victorian quarries, this route Mountains Vineyards offers up a taste of the entire Knoll Farm Cotswold landscape in 4½ Charlton Kings Common Wood sheltered and windswept miles. Devil’s Chimney Cot 3 swold Way Distance: 4½ miles or 7.2km Hartley Hill Duration: 4 2½ - 3 hrs Leckhampton Hill Difficulty: Moderate to easy, no stiles, some Chipping 2 steep sections. Campden Wistley Grove Public transport: A435 No. 51 bus (Cheltenham - Leckhampton Cirencester - Swindon). Ask for y Windmill Seven Springs stop. (See the a W Farm A436 d ‘Explore the Cotswolds’ public l o BUS STOP transport guide or visit www. w s traveline.info t Bath o C Start 1 Start/Finish: 0 Miles 0.5 Grid reference SO 967/170 (OS Explorer sheet 179) 0 Kms 0.5 9/17 Postcode GL53 9NG Refreshments: the edge of the scarp for just over At this point leave the Cotswold to follow the road after it becomes Pub at Seven Springs. a mile (1.6km), eventually passing Way, head for the marker post and an unmade track for half a mile Parking through ramparts just beyond some follow the steepish path leading (0.8 km) along the bottom of the Lay-by opposite Seven springs pub. pine trees. Enter into this Iron diagonally down across the slope escarpment, eventually forking right Age hillfort, built between 500 and Alternative start points are from into a wooded area. -

THE MANORIAL ESTATES of LECKHAMPTON by Terry Moore

Reprinted from Gloucestershire History No. 16 (2002) pages 9-22 THE MANORIAL ESTATES OF LECKHAMPTON By Terry Moore-Scott Introduction their estate was held directly from the Crown by the service of dispenser in the king's household? An automatic reaction upon first encountering the At the same time, however, the Despensers' estate subject of Leckhampton's manorial history is to also included land held from the manor of think of Leckhampton Court and of the manor Cheltenham and land ‘on the hill‘ held from the with which it has been associated since earliest neighbouring manor of Coberley, then in the times. After all, the history of the manor extends hands of lords of Berkeley. Indeed these back to Saxon times and its descent is traceable relationships with Cheltenham and Coberley through the great house of Despenser and later a continued for centuries and one 16th century lord series of prominent Gloucestershire families, the of Leckhampton briefly leased Cheltenham manor Giffards, Norwoods and Tryes, related by from the Crown. In 1247 Henry III had granted marriage. Together the three families formed a Cheltenham manor, and thereby the overlordship line of mainly resident lords of Leckhampton that of Leckhampton, along with other estates to the continued for over 500 years until the estate was Norman abbey of Fecamp in retum for the ports of sold at the end of the 19th century. Less well Rye and Winchelsea. Fecamp's ownership ended known is that Leckhampton possessed two other in 1414 when Henry V seized the English estates possible manors. The first, and less recorded, can of alien abbeys. -

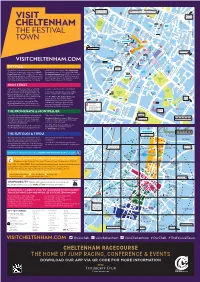

Cheltenham Racecourse (Map Ref E1) the Everyman Theatre (Map Ref D4) D H M B E Lk R S a Park Priory Th D Ed

n Tesco t e A4019 to Tewkesbury, t e e Y d r n l R e Pittville Pump Room, Leisure at Cheltenham, W d M5 North Junction 10, a e U r a EL R d L t L b B I l R T S Racecourse, Park & Ride and A435 to Evesham N G M Gallagher Retail Park ’s D T S D l s O A E D R ’ A N R R ER u l RO P T a u O A S h k D E P a R n C Y t c t U t P r i B4632 to A t e w O S t o w L e e C M a G S s r la d A W N t r L Winchcombe n e e e A 4 r n R 0 E u S S c e t u q e H l 1 L r y u l n & Broadway 9 S n a S i e O S B e r PO W l e e v d IN l E l t D t D O a v t a A e N C V i O n A l E R a M e O r P R r A u en Y t t D n ce R Winston D o R S e o BU s ad T M H g e PITTVILLE Churchill I r n ES a G n t P H i o PR r S o CIRCUS k Memorial S K t T t s M r e T ’ E t e R l S Holst t E l S Gardens E u s a e ’ t E R t r a Birthplace n r t T e e e P T S g e e e S Trinity Museum d t t r c t r n t S S o t a Long Millbrook l D S o S e S The Church q t e P Stay r r N Roundabout e i G a e t t h u v Brewery A Se h t t t n lki H B S L rk S o s S e r a B tre r i e et o n Quarter d o T L lm n r r e n R on G o o n g N y t e i o R y v f a t d G All Saints t e n O i len b e x s S t f W a n al o H s e T P i e Y l S t O t w o tre Church a u D et a g M r e rk e r S re Citizens S o t y n St t P r a T r St w B s A Warwick t e e S a n C N y s R S D Advice n o S e h t a h G Place d s W a & A h e A m g P t e R a o a e r E e n y t o St James’ r J n c T l r O K e i s o ’S d t b n a o e R R R n n n o l d O n o e a W s Roundabout p e N A e p m a r n R P n D b e n l r r S R k Chester e a C r t d o A H l -

Leckhampton Rovers Football Club Introductions

Leckhampton Rovers Football Club Introductions Enzo Scognamiglio, Club Chairman and Welfare Officer David Pitts, Club Secretary, Treasurer and Welfare Officer Mark Beaney, Team Coach and Future Development Projects Andy Pitchford, Team Coach and Future Development Projects Club History Formed in 1996 by a few Dad’s, of which Dave Pitts was one, to provide facilities for 20 boys and girls who wanted to kick a ball around. Twenty-two years later, we now have: - Teams A Veterans Team A Men’s Team – 35 players 28 Youth teams – Ages ranging from U8 to U18 A Girls Academy – SSE Wildcats An Academy – Ages 4 to 8 – 98 children, boys and girls 503 Registered Youth Players How we have grown!! Coaches and Parent Helpers We have 37 FA Level 1 in Coaching Football qualified coaches We have 7 FA Level 2 qualified coaches We have 1 coach with his Level 3 UEFA B Licence We have 41+ Parent helpers who have had DBS completed All of whom are VOLUNTEERS Current Match Day Pitches Burrows Sports Field All Saints Academy Hartpury College King George V Playing Fields Naunton Park Playing Fields Oxstalls Sports Park, Gloucester Uni of Glos, The Folley Winchcombe School Current Training Facilities All Saints Academy Balcarras School Bournside School Cheltenham College Henley Bank School, Brockworth University of Gloucestershire’s The Park Campus Winchcombe School https://leckhamptonrovers.co.uk Please follow us. Website Facebook Twitter VISION 25 What do we want LRFC to look like in 2025? Best club in Gloucestershire Fastest growing -

JCS Issues and Questions Consultation

JCS Issues and Questions Consultation Foreword In 2008 the Councils of Gloucester City, Tewkesbury Borough and Cheltenham Borough decided to prepare a joint development plan. This will have many benefits to planning a sustainable future for all three Council areas and the approach is supported by Gloucestershire County Council. This consultation document is the first stage in producing the joint development plan and has regard to the latest Draft of the Regional Spatial Strategy (RSS) for the South West. Despite Government promises, the RSS has still not been formally published. The Government advises that the Draft RSS should be used as a material planning consideration in the planning process when considering applications for proposals contained within it. The development industry therefore may not wait for the Government to publish the RSS and the Planning Inspectorate is likely to come under pressure to make decisions on planning appeals in advance of its publication. Cheltenham Borough, Gloucester City and Tewkesbury Borough together with Gloucestershire County Council have various significant objections to key aspects of the RSS, particularly in relation to unjustified urban extensions and unnecessary incursion into the Green Belt arising from its proposals for increased growth to unprecedented levels.. Although the Councils remain opposed to the RSS, we feel it is vital to put plans in place to help secure proper infrastructure should applications come forward for proposals within the Draft RSS. It is also necessary, for the good planning of the area, to ensure that an up-to-date development plan is in place to guide future sustainable development and safeguard environmental, social, economic and other key interests.