Questions in Nc Zoo Society Members Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reciprocal Zoos and Aquariums

Reciprocity Please Note: Due to COVID-19, organizations on this list may have put their reciprocity program on hold as advance reservations are now required for many parks. We strongly recommend that you call the zoo or aquarium you are visiting in advance of your visit. Thank you for your patience and understanding during these unprecedented times. Wilds Members: Members of The Wilds receive DISCOUNTED or FREE admission to the AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums on the list below. Wilds members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. Each zoo maintains its own discount policies, and The Wilds strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo. Each zoo reserves the right to limit the amount of discounts, and may not offer discounted tickets for your entire family size. *This list is subject to change at any time. Visiting The Wilds from Other Zoos: The Wilds is proud to offer a 50% discount on the Open-Air Safari tour to members of the AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums on the list below. The reciprocal discount does not include parking. If you do not have a valid membership card, please contact your zoo’s membership office for a replacement. This offer cannot be combined with any other offers or discounts, and is subject to change at any time. Park capacity is limited. Due to COVID-19 advance reservations are now required. You may make a reservation by calling (740) 638-5030. You must present your valid membership card along with your photo ID when you check in for your tour. -

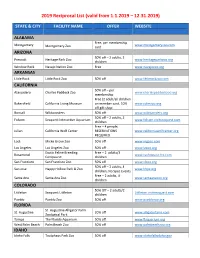

Reciprocal Zoo List 2019 for Website

2019 Reciprocal List (valid from 1.1.2019 – 12.31.2019) STATE & CITY FACILITY NAME OFFER WEBSITE ALABAMA Free, per membership Montgomery www.montgomeryzoo.com Montgomery Zoo card ARIZONA 50% off – 2 adults, 3 Prescott Heritage Park Zoo www.heritageparkzoo.org children Window Rock Navajo Nation Zoo Free www.navajozoo.org ARKANSAS Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% off www.littlerockzoo.com CALIFORNIA 50% off – per Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo www.charlespaddockzoo.org membership Free (2 adult/all children Bakersfield California Living Museum on member card, 10% www.calmzoo.org off gift shop Bonsall Wildwonders 50% off www.wildwonders.org 50% off – 2 adults, 2 Folsom Seaquest Interactive Aquarium www.folsom.visitseaquest.com children Free – 4 people; Julian California Wolf Center RESERVATIONS www.californiawolfcenter.org REQUIRED Lodi Micke Grove Zoo 50% off www.mgzoo.com Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% off www.lazoo.org Exotic Feline Breeding Free – 2 adults/3 Rosamond www.cathopuise.fcc.com Compound children San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% off www.sfzoo.org 50% off – 2 adults, 4 San Jose Happy Hollow Park & Zoo www.hhpz.org children, No Spec Events Free – 2 adults, 4 Santa Ana Santa Ana Zoo www.santaanazoo.org children COLORADO 50% Off – 2 adults/2 Littleton Seaquest Littleton Littleton.visitseaquest.com children Pueblo Pueblo Zoo 50% off www.pueblozoo.org FLORIDA St. Augustine Alligator Farm St. Augustine 20% off www.alligatorfarm.com Zoological Park Tampa The Florida Aquarium 50% off www.flaquarium.org West Palm Beach Palm Beach Zoo 50% off www.palmbeachzoo.org IDAHO Idaho Falls Tautphaus Park Zoo 50% off www.idahofallsidaho.gov 2019 Reciprocal List (valid from 1.1.2019 – 12.31.2019) Free – 2 adults, 5 Pocatello Pocatello Zoo www.zoo.pocatello.us children ILLINOIS Free – 2 adults, 3 Springfield Henson Robinson Zoo children. -

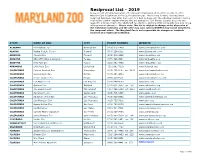

Reciprocal List

Reciprocal List - 2019 Below is a list of institutions which offer discounted admission (50% off) to members of The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore for the 2019 calendar year. Please keep in mind, zoos may have reciprocal definitions that differ from ours. It is best to check with the individual institution before your visit to confirm exactly what benefits are available to Zoo friends. Usually, discounts are applied to a group of up to two adults and two children, and any additional members in your group will pay normal admission. Please note: This list is subject to change at the discretion of the individual institution and the offer may vary. Special EVENTS may not be included in the reciprocal offers. The Maryland Zoo is not responsible for charges or incidents incurred at a reciprocal institution. STATE NAME OF ZOO CITY PHONE NUMBER WEBSITE ALABAMA Birmingham Zoo Birmingham (205) 879-0409 www.birminghamzoo.com ALASKA Alaska SeaLife Center Seward (907) 224-6355 www.alaskasealife.org ARIZONA Phoenix Zoo Phoenix (602) 914-4365 www.phoenixzoo.org ARIZONA SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium Tempe (877) 526-3960 www.visitsealife.com ARIZONA Reid Park Zoo Tucson (520) 881-4753 www.reidparkzoo.org ARKANSAS Little Rock Zoo Little Rock (501)661-7218 www.littlerock.org CALIFORNIA Charles Paddock Zoo Atascadero (805) 461-5080 ext. 2105 www.charlespaddockzoo.org CALIFORNIA Sequoia Park Zoo Eureka (707) 441-4263 www.sequoiaparkzoo.net CALIFORNIA Fresno Chaffee Zoo Fresno (559) 498-5921 www.fresnochaffeezoo.com CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Zoo Los Angeles (323) 644-4759 www.lazoo.org CALIFORNIA Oakland Zoo Oakland (510) 632-9525 ext. -

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List – Updated July 1, 2021 The following AZA-accredited institutions have agreed to offer a 50% discount on admission to visiting Santa Barbara Zoo Members who present a current membership card and valid picture ID at the entrance. Please note: Each participating zoo or aquarium may treat membership categories, parking fees, guest privileges, and additional benefits differently. Reciprocation policies subject to change without notice. Please call to confirm before you visit. Iowa Rosamond Gifford Zoo at Burnet Park - Syracuse Alabama Blank Park Zoo - Des Moines Seneca Park Zoo – Rochester Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium - Staten Island Zoo - Staten Island Alaska Dubuque Trevor Zoo - Millbrook Alaska SeaLife Center - Seaward Kansas Utica Zoo - Utica Arizona The David Traylor Zoo of Emporia - Emporia North Carolina Phoenix Zoo - Phoenix Hutchinson Zoo - Hutchinson Greensboro Science Center - Greensboro Reid Park Zoo - Tucson Lee Richardson Zoo - Garden Museum of Life and Science - Durham Sea Life Arizona Aquarium - Tempe City N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher - Kure Beach Arkansas Rolling Hills Zoo - Salina N.C. Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores - Atlantic Beach Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Sedgwick County Zoo - Wichita N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island - Manteo California Sunset Zoo - Manhattan Topeka North Carolina Zoological Park - Asheboro Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoological Park - Topeka Western N.C. (WNC) Nature Center – Asheville Cabrillo Marine Aquarium -

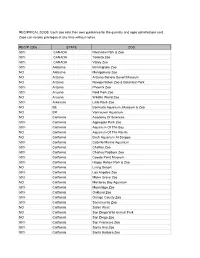

2006 Reciprocal List

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits List created by © birdsandbats on www.zoochat.com. Last Updated: 19/08/2019 African Clawless Otter (2 holders) Metro Richmond Zoo San Diego Zoo American Badger (34 holders) Alameda Park Zoo Amarillo Zoo America's Teaching Zoo Bear Den Zoo Big Bear Alpine Zoo Boulder Ridge Wild Animal Park British Columbia Wildlife Park California Living Museum DeYoung Family Zoo GarLyn Zoo Great Vancouver Zoo Henry Vilas Zoo High Desert Museum Hutchinson Zoo 1 Los Angeles Zoo & Botanical Gardens Northeastern Wisconsin Zoo & Adventure Park MacKensie Center Maryland Zoo in Baltimore Milwaukee County Zoo Niabi Zoo Northwest Trek Wildlife Park Pocatello Zoo Safari Niagara Saskatoon Forestry Farm and Zoo Shalom Wildlife Zoo Space Farms Zoo & Museum Special Memories Zoo The Living Desert Zoo & Gardens Timbavati Wildlife Park Turtle Bay Exploration Park Wildlife World Zoo & Aquarium Zollman Zoo American Marten (3 holders) Ecomuseum Zoo Salomonier Nature Park (atrata) ZooAmerica (2.1) 2 American Mink (10 holders) Bay Beach Wildlife Sanctuary Bear Den Zoo Georgia Sea Turtle Center Parc Safari San Antonio Zoo Sanders County Wildlife Conservation Center Shalom Wildlife Zoo Wild Wonders Wildlife Park Zoo in Forest Park and Education Center Zoo Montana Asian Small-clawed Otter (38 holders) Audubon Zoo Bright's Zoo Bronx Zoo Brookfield Zoo Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Dallas Zoo Denver Zoo Disney's Animal Kingdom Greensboro Science Center Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens 3 Kansas City Zoo Houston Zoo Indianapolis -

State City Zoo Or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact

Updated March 25th, 2021 State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone # CANADA Calgary -Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Katie Frost 403-232-9386 Granby - Quebe Granby Zoo 50% Mireille Forand 450-372-9113 x2103 Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Membership Dept 416-392-9101 Winnipeg - ManiAssiniboine Park Zoo 50% Leah McDonald 204-927-6062 If the zoo or aquarium to which MEXICO León Parque Zoológico de León 50% David Rocha 52-477-210-2335 you belong has 50% in the Reciprocity column, you can Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Patty Pendleton 205-879-0409 x232 expect to receive a 50% discount Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Shannon Wolf 907-224-6355 on admission at all the zoos and Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo 50% Membership Dept 602-914-4393 aquariums on this list (except, of course, those that are FREE TO Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Membership Dept 877-526-3960 THE PUBLIC). Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Membership Dept 520-881-4753 ALWAYS CALL AHEAD* Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Kelli Enz 501-371-4589 If the zoo or aquarium to which California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 100% & 50% Becky Maxwell 805-461-5080 x2105 you belong has 100% and 50% Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 100% & 50% Kathleen Juliano 707-441-4263 in the Reciprocity column, you can expect to receive free Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Membership Office559-498-5921 admission to the zoos and Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Membership Dept 323-644-4759 aquariums that also have 100% Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Membership Dept 510-632-9525 x160 and 50% in the Reciprocity column and those that are FREE Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Elisa Escobar 760-346-5694 x2111 TO THE PUBLIC; and a 50% Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Membership Dept 916-808-5888 discount on admission to the San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Jaz Cariola 415-623-5310 zoos and aquariums that have 50% in the Reciprocity column. -

Testimony Presented to the Kansas House Committee on Federal and State Affairs

Testimony Presented to the Kansas House Committee on Federal and State Affairs. March 22, 2017 in Support of HB2276: Amending statutes concerning dangerous regulated animals. Good morning. My name is Robert L. Jenkins and I am the Executive Director of the Rolling Hills Zoo in Salina, Kansas. Today I am speaking on behalf of the seven Kansas Zoos who are Accredited Members of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), the nation’s premiere accrediting body for public zoological institutions. They are the Rolling Hills Zoo/Salina, the Topeka Zoo/Topeka, the Sedgwick County Zoo/Wichita, the Sunset Zoo/Manhattan, the David Traylor Zoo/Emporia, the Lee Richardson Zoo/Garden City and the Hutchinson Zoo/Hutchinson. The directors of these seven AZA accredited institutions have had the opportunity to review the proposed amendments before you today and after discussion have agreed unanimously to the intent and language of HB2276. This is due to the fact that they are accredited members of the AZA and as such, have agreed to support the positions and policies of the AZA. In preparing my comments for you today, I wrestled with how much I should prepare and how long should I speak to the issue. In fact, there is little need for me to do so as the AZA has already prepared a position paper that has been approved by its Board of Directors in 2015 entitled Personal Possession of Non-Human Primates. This paper was developed by the membership of AZA, particularly its specialists in non-human primate care and welfare. The paper, while appearing long at first, only seems so due to the large number of scientific publications that are referenced to support the position that the personal possession of non-human primates by the general public has significant negative implications for animal health and welfare and, equally importantly, public health and safety as well. -

RECIPROCAL LIST from YOUR ORGANIZATION and CALL N (309) 681-3500 US at (309) 681-3500 to CONFIRM

RECIPROCAL LOCAL HIGHLIGHTS RULES & POLICIES Enjoy a day or weekend trip Here are some important rules and to these local reciprocal zoos: policies regarding reciprocal visits: • FREE means free general admission and 50% off means 50% off general Less than 2 Hours Away: admission rates. Reciprocity applies to A Peoria Park District Facility the main facility during normal operating Miller Park Zoo, Bloomington, IL: days and hours. May exclude special Peoria Zoo members receive 50% off admission. exhibits or events requiring extra fees. RECIPROCAL Henson Robinson Zoo, Springfield, IL: • A membership card & photo ID are Peoria Zoo members receive FREE admission. always required for each cardholder. LIST Scovill Zoo, Decatur, IL: • If you forgot your membership card Peoria Zoo members receive 50% off admission. at home, please call the Membership Office at (309) 681-3500. Please do this a few days in advance of your visit. More than 2 Hours Away: • The number of visitors admitted as part of a Membership may vary depending St. Louis Zoo, St. Louis, MO: on the policies and level benefits of Peoria Zoo members receive FREE general the zoo or aquarium visited. (Example, admission and 50% off Adventure Passes. some institutions may limit number of children, or do not allow “Plus” guests.) Milwaukee Zoo, Milwaukee, WI: Peoria Zoo members receive FREE admission. • This list may change at anytime. Please call each individual zoo or aquarium Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, IL: BEFORE you visit to confirm details and restrictions! Peoria Zoo members receive FREE general admission and 10% off retail and concessions. DUE TO COVID-19, SOME FACILITIES Cosley Zoo, Wheaton, IL: MAY NOT BE PARTICIPATING. -

RECIPROCAL LIST from YOUR ORGANIZATION and CALL N (309) 681-3500 US at (309) 681-3500 to CONFIRM

RECIPROCAL LOCAL HIGHLIGHTS RULES & POLICIES Enjoy a day or weekend trip Here are some important rules and to these local reciprocal zoos: policies regarding reciprocal visits: • FREE means free general admission and 50% off means 50% off general Less than 2 Hours Away: admission rates. Reciprocity applies to A Peoria Park District Facility the main facility during normal operating Miller Park Zoo, Bloomington, IL: days and hours. May exclude special Peoria Zoo members receive 50% off admission. exhibits or events requiring extra fees. RECIPROCAL Niabi Zoo, Coal Valley, IL: • A membership card & photo ID are Peoria Zoo members receive FREE admission. always required for each cardholder. LIST Scovill Zoo, Decatur, IL: • If you forgot your membership card Peoria Zoo members receive 50% off admission. at home, please call the Membership Office at (309) 681-3500. Please do this a few days in advance of your visit. More than 2 Hours Away: • The number of visitors admitted as part of a Membership may vary depending St. Louis Zoo, St. Louis, MO: on the policies and level benefits of Peoria Zoo members receive FREE general the zoo or aquarium visited. (Example, admission and 50% off Adventure Passes. some institutions may limit number of children, or do not allow “Plus” guests.) Milwaukee Zoo, Milwaukee, WI: Peoria Zoo members receive FREE admission. • This list may change at anytime. Please call each individual zoo or aquarium Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, IL: BEFORE you visit to confirm details and Peoria Zoo members receive FREE general restrictions! admission and 10% off retail and concessions. DUE TO COVID-19, SOME FACILITIES Cosley Zoo, Wheaton, IL: MAY NOT BE PARTICIPATING. -

Reciprocal Zoos & Aquariums

Reciprocal Zoos & Aquariums This list includes over 150 zoos and aquariums that current Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium members can visit at a reduced rate. Please contact the zoo or aquarium you are planning to visit in advance of your trip to confirm reciprocity and determine benefits. Remember to present your membership card and bring photo ID. Please note: - If you are a member of any zoo on the list below you can access Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium at a 50% discount of our general admission prices at the front gate. Please read the information at the bottom of this page before your visit. - PDZA membership reciprocity benefits DO NOT apply to Woodland Park Zoo and vice versa. - Reciprocity benefits are awarded to those individuals specifically named on your Zoo membership pass only. Guest passes and parking passes from reciprocal zoo memberships will not be honored. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA by State ALABAMA FLORIDA (cont) Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham St Augustine Alligator Farm – St. Augustine ALASKA The Florida Aquarium - Tampa Alaska Sealife Center - Seward West Palm Beach – Palm Beach Zoo ARIZONA Reid Park Zoo - Tucson ZooTampa at Lowry Park – Tampa Zoo Miami - Miami Phoenix Zoo – Phoenix GEORGIA SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium - Tempe Zoo Atlanta – Atlanta ARKANSAS IDAHO Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Idaho Falls Zoo at Tautphaus Park - Idaho Falls CALIFORNIA Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoo Boise – Boise Cabrillo Marine Aquarium – San Pedro ILLINOIS Charles Paddock Zoo - Atascadero Cosley Zoo – Wheaton CuriOdyssey - San Mateo -

Conservation & Research

CONNECT January 2013 FEATURES 8 A NEW LOOK TO THE AZA ANIMAL HEALTH COMMITTEE PAM DENNIS 10 THE GREAT APE HEART PROJECT Changing the Way Zoos Work Together RACHEL MCNABB 14 THE ROLE OF ZOOS IN ONE HEALTH SHARON L. DEEM & PAM DENNIS 16 WELCOME Y'ALL! AZA's Mid-Year Meeting Comes to Charleston, S.C. 26 CONSERVATION SPOTLIGHT 37 PARTNERS COMMITTED TO ANIMAL HEALTH IN EVERY ISSUE 3 A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT & CEO 7 CONSERVATION & RESEARCH 21 MEMBER NEWS 28 GREEN TALES 30 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR 31 BIRTHS & HATCHINGS 36 CEF UPDATE 39 EXHIBITS ON THE COVER The Great Ape Heart Project is the world’s first attempt to comprehend, diagnose, track, 40 ANNOUNCEMENTS and treat heart disease in great apes, a leading killer of some of the most charismatic ani- 44 MEMBER UPDATES mals living in AZA collections. Supported by the Great Ape Taxon Advisory Group (TAG) and bastioned by the combined efforts of four Species Survival Plans® (SSPs), the project 45 INDEX OF ADVERTISERS has become an industry model for inter-zoo collaboration. The silverback gorilla on the cover is a member of the bachelor group at Disney’s Animal Kingdom. 46 CALENDAR GORILLA © GENE DUNCAN Designs for Life From concept through completion, to troubleshooting and retrotting existing systems, public zoos and aquariums worldwide have trusted Pentair’s WaterLife Design Group. Contact us today to nd out how we can help you. Web: WaterLifeDesign.com Email: [email protected] Phone: 407-472-0525 • Fax: 407-886-1304 2395 Apopka Blvd., Apopka, FL 32703 Find us on WaterLife Design Group is now a proud member of the Pentair family.