Evolution of K-Rich Magmas Derived from a Net Veined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fingerprints of Kamafugite-Like Magmas in Mesozoic Lamproites of the Aldan Shield: Evidence from Olivine and Olivine-Hosted Inclusions

minerals Article Fingerprints of Kamafugite-Like Magmas in Mesozoic Lamproites of the Aldan Shield: Evidence from Olivine and Olivine-Hosted Inclusions Ivan F. Chayka 1,2,*, Alexander V. Sobolev 3,4, Andrey E. Izokh 1,5, Valentina G. Batanova 3, Stepan P. Krasheninnikov 4 , Maria V. Chervyakovskaya 6, Alkiviadis Kontonikas-Charos 7, Anton V. Kutyrev 8 , Boris M. Lobastov 9 and Vasiliy S. Chervyakovskiy 6 1 V. S. Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia; [email protected] 2 Institute of Experimental Mineralogy, Russian Academy of Sciences, 142432 Chernogolovka, Russia 3 Institut des Sciences de la Terre (ISTerre), Université de Grenoble Alpes, 38041 Grenoble, France; [email protected] (A.V.S.); [email protected] (V.G.B.) 4 Vernadsky Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical Chemistry, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 5 Department of Geology and Geophysics, Novosibirsk State University, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia 6 Institute of Geology and Geochemistry, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 620016 Yekaterinburg, Russia; [email protected] (M.V.C.); [email protected] (V.S.C.) 7 School of Chemical Engineering and Advanced Materials, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; [email protected] 8 Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 683000 Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Russia; [email protected] 9 Institute of Mining, Geology and Geotechnology, Siberian Federal University, 660041 Krasnoyarsk, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-985-799-4936 Received: 17 February 2020; Accepted: 6 April 2020; Published: 9 April 2020 Abstract: Mesozoic (125–135 Ma) cratonic low-Ti lamproites from the northern part of the Aldan Shield do not conform to typical classification schemes of ultrapotassic anorogenic rocks. -

Mineralogy and Chemistry of Rare Earth Elements in Alkaline Ultramafic Rocks and Fluorite in the Western Kentucky Fluorspar District Warren H

Mineralogy and Chemistry of Rare Earth Elements in Alkaline Ultramafic Rocks and Fluorite in the Western Kentucky Fluorspar District Warren H. Anderson Report of Investigations 8 doi.org/10.13023/kgs.ri08.13 Series XIII, 2019 Cover Photo: Various alkaline ultramafic rocks showing porphyritic, brecciated, and aphanitic textures, in contact with host limestone and altered dike texture. From left to right: • Davidson North dike, Davidson core, YH-04, 800 ft depth. Lamprophyre with calcite veins, containing abundant rutile. • Coefield area, Billiton Minner core BMN 3. Intrusive breccia with lamprophyric (al- nöite) matrix. • Maple Lake area, core ML-1, 416 ft depth. Lamprophyre intrusive. • Maple Lake area, core ML-2, 513 ft depth. Lamprophyre (bottom) in contact with host limestone (top). Kentucky Geological Survey University of Kentucky, Lexington Mineralogy and Chemistry of Rare Earth Elements in Alkaline Ultramafic Rocks and Fluorite in the Western Kentucky Fluorspar District Warren H. Anderson Report of Investigations 8 doi.org/10.13023/kgs.ri08.13 Series XIII, 2019 Our Mission The Kentucky Geological Survey is a state-supported research center and public resource within the University of Kentucky. Our mission is to sup- port sustainable prosperity of the commonwealth, the vitality of its flagship university, and the welfare of its people. We do this by conducting research and providing unbiased information about geologic resources, environmen- tal issues, and natural hazards affecting Kentucky. Earth Resources—Our Common Wealth www.uky.edu/kgs © 2019 University of Kentucky For further information contact: Technology Transfer Officer Kentucky Geological Survey 228 Mining and Mineral Resources Building University of Kentucky Lexington, KY 40506-0107 Technical Level General Intermediate Technical Statement of Benefit to Kentucky Rare earth elements are used in many applications in modern society, from cellphones to smart weapons systems. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9412018 Integrated approach to diamond exploration in the north-central United States Memmi, John Michael, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1993 Copyright ©1993 by Memmi, John Michael. -

Geology of the Crater of Diamonds State Park and Vicinity, Pike County, Arkansas

SPS-03 STATE OF ARKANSAS ARKANSAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Bekki White, State Geologist and Director STATE PARK SERIES 03 GEOLOGY OF THE CRATER OF DIAMONDS STATE PARK AND VICINITY, PIKE COUNTY, ARKANSAS by J. M. Howard and W. D. Hanson Little Rock, Arkansas 2008 STATE OF ARKANSAS ARKANSAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Bekki White, State Geologist and Director STATE PARK SERIES 03 GEOLOGY OF THE CRATER OF DIAMONDS STATE PARK AND VICINITY, PIKE COUNTY, ARKANSAS by J. M. Howard and W. D. Hanson Little Rock, Arkansas 2008 STATE OF ARKANSAS Mike Beebe, Governor ARKANSAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Bekki White, State Geologist and Director COMMISSIONERS Dr. Richard Cohoon, Chairman………………………………………....Russellville William Willis, Vice Chairman…………………………………...…….Hot Springs David J. Baumgardner………………………………………….………..Little Rock Brad DeVazier…………………………………………………………..Forrest City Keith DuPriest………………………………………………………….….Magnolia Becky Keogh……………………………………………………...……..Little Rock David Lumbert…………………………………………………...………Little Rock Little Rock, Arkansas 2008 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..................... 1 Geology…………………………………………………………………………………………... 1 Prairie Creek Diatreme Rock Types……………………………….…………...……...………… 3 Mineralogy of Diamonds…………………….……………………………………………..……. 6 Typical shapes of Arkansas diamonds…………………………………………………………… 6 Answers to Frequently Asked Questions……………..……………………………….....……… 7 Definition of Rock Types……………………………………………………………………… 7 Formation Processes.…...…………………………………………………………….....…….. 8 Search Efforts……………...……………………………...……………………...………..…. -

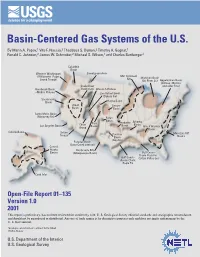

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. by Marin A

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. By Marin A. Popov,1 Vito F. Nuccio,2 Thaddeus S. Dyman,2 Timothy A. Gognat,1 Ronald C. Johnson,2 James W. Schmoker,2 Michael S. Wilson,1 and Charles Bartberger1 Columbia Basin Western Washington Sweetgrass Arch (Willamette–Puget Mid-Continent Rift Michigan Basin Sound Trough) (St. Peter Ss) Appalachian Basin (Clinton–Medina Snake River and older Fms) Hornbrook Basin Downwarp Wasatch Plateau –Modoc Plateau San Rafael Swell (Dakota Fm) Sacramento Basin Hanna Basin Great Denver Basin Basin Santa Maria Basin (Monterey Fm) Raton Basin Arkoma Park Anadarko Los Angeles Basin Chuar Basin Basin Group Basins Black Warrior Basin Colville Basin Salton Mesozoic Rift Trough Permian Basin Basins (Abo Fm) Paradox Basin (Cane Creek interval) Central Alaska Rio Grande Rift Basins (Albuquerque Basin) Gulf Coast– Travis Peak Fm– Gulf Coast– Cotton Valley Grp Austin Chalk; Eagle Fm Cook Inlet Open-File Report 01–135 Version 1.0 2001 This report is preliminary, has not been reviewed for conformity with U. S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature, and should not be reproduced or distributed. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U. S. Government. 1Geologic consultants on contract to the USGS 2USGS, Denver U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey BASIN-CENTERED GAS SYSTEMS OF THE U.S. DE-AT26-98FT40031 U.S. Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory Contractor: U.S. Geological Survey Central Region Energy Team DOE Project Chief: Bill Gwilliam USGS Project Chief: V.F. -

Diamond Evaluation of the Prairie Creek Lamproite Province, Arkansas, Usa

DIAMOND EVALUATION OF THE PRAIRIE CREEK LAMPROITE PROVINCE, ARKANSAS, USA Dennis Dunn, University of Texas at Austin, USA REGIONAL GEOLOGY from the 105 tonnes of material from the Twin Knobs 2 lamproite (Figure 2). The calculated diamond grade The Prairie Creek lamproite province consists of seven throughout the Twin Knobs 2 lamproite was known diamondiferous lamproite vents within a belt that approximately 0.04 carats per 100 tonnes. The calculated extends for 5 km, in a northeasterly direction from the average diamond content of both intrusions was an order largest of the vents, Prairie Creek (Figure 1). The Prairie of magnitude less that that observed at the Prairie Creek Creek lamproite has a K-Ar age of ~106 Ma (Gogineni lamproite which yielded an average diamond grade of and others, 1978). The northeast alignment is sub-parallel 0.57 carats per 100 tonnes (Morgan Worldwide Mining to the northeast-trending Reelfoot Rift located ~100 km Consultants, 1997), and for the Twin Knobs 1 lamproite east of the intrusions. The lamproite province straddles which yielded a grade of 0.17 carats per 100 tonnes the geologic and physiographic boundary between the (Waldman and others, 1987). Cenozoic Gulf Coastal Plain and the Paleozoic Ouachita Mountains. It is widely believed that the lamproite province lies near the southern margin of the North American craton which consists of 1.3 to 1.5 Ga granite- rhyolite terrane (Van Schmus and others, 1986). Three previously unexplored Arkansas lamproites were delineated and evaluated during the 1980’s. The three vents – Black Lick (10 hectares), Twin Knobs 2 (2 hectares) and Timberlands (<1 hectare) -- were intruded into the Lower Cretaceous Trinity Group and are overlain unconformably by the Late Cretaceous Tokio Formation rocks. -

Gems and Placers—A Genetic Relationship Par Excellence

Article Gems and Placers—A Genetic Relationship Par Excellence Dill Harald G. Mineralogical Department, Gottfried-Wilhelm-Leibniz University, Welfengarten 1, D-30167 Hannover, Germany; [email protected] Received: 30 August 2018; Accepted: 15 October 2018; Published: 19 October 2018 Abstract: Gemstones form in metamorphic, magmatic, and sedimentary rocks. In sedimentary units, these minerals were emplaced by organic and inorganic chemical processes and also found in clastic deposits as a result of weathering, erosion, transport, and deposition leading to what is called the formation of placer deposits. Of the approximately 150 gemstones, roughly 40 can be recovered from placer deposits for a profit after having passed through the “natural processing plant” encompassing the aforementioned stages in an aquatic and aeolian regime. It is mainly the group of heavy minerals that plays the major part among the placer-type gemstones (almandine, apatite, (chrome) diopside, (chrome) tourmaline, chrysoberyl, demantoid, diamond, enstatite, hessonite, hiddenite, kornerupine, kunzite, kyanite, peridote, pyrope, rhodolite, spessartine, (chrome) titanite, spinel, ruby, sapphire, padparaja, tanzanite, zoisite, topaz, tsavorite, and zircon). Silica and beryl, both light minerals by definition (minerals with a density less than 2.8–2.9 g/cm3, minerals with a density greater than this are called heavy minerals, also sometimes abbreviated to “heavies”. This technical term has no connotation as to the presence or absence of heavy metals), can also appear in some placers and won for a profit (agate, amethyst, citrine, emerald, quartz, rose quartz, smoky quartz, morganite, and aquamarine, beryl). This is also true for the fossilized tree resin, which has a density similar to the light minerals. -

Ncomms7837.Pdf

ARTICLE Received 3 Oct 2014 | Accepted 3 Mar 2015 | Published 17 Apr 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7837 Did diamond-bearing orangeites originate from MARID-veined peridotites in the lithospheric mantle? Andrea Giuliani1, David Phillips1, Jon D. Woodhead1, Vadim S. Kamenetsky2, Marco L. Fiorentini3, Roland Maas1, Ashton Soltys1 & Richard A. Armstrong4 Kimberlites and orangeites (previously named Group-II kimberlites) are small-volume igneous rocks occurring in diatremes, sills and dykes. They are the main hosts for diamonds and are of scientific importance because they contain fragments of entrained mantle and crustal rocks, thus providing key information about the subcontinental lithosphere. Orangeites are ultrapotassic, H2O and CO2-rich rocks hosting minerals such as phlogopite, olivine, calcite and apatite. The major, trace element and isotopic compositions of orangeites resemble those of intensely metasomatized mantle of the type represented by MARID (mica-amphibole- rutile-ilmenite-diopside) xenoliths. Here we report new data for two MARID xenoliths from the Bultfontein kimberlite (Kimberley, South Africa) and we show that MARID-veined mantle has mineralogical (carbonate-apatite) and geochemical (Sr-Nd-Hf-O isotopes) characteristics compatible with orangeite melt generation from a MARID-rich source. This interpretation is supported by U-Pb zircon ages in MARID xenoliths from the Kimberley kimberlites, which confirm MARID rock formation before orangeite magmatism in the area. 1 School of Earth Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, 3010 Victoria, Australia. 2 School of Physical Sciences, University of Tasmania, Hobart, 7001 Tasmania, Australia. 3 Centre for Exploration Targeting, Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Core to Crust Fluid Systems, School of Earth and Environment, University of Western Australia, Crawley, 6009 Western Australia, Australia. -

Diamondiferous Kimberlites in Central India Synchronous with Deccan flood Basalts

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 290 (2010) 142–149 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Diamondiferous kimberlites in central India synchronous with Deccan flood basalts Bernd Lehmann a,⁎, Ray Burgess b, Dirk Frei c, Boris Belyatsky d, Datta Mainkar e, Nittala V. Chalapathi Rao a,f, Larry M. Heaman g a Mineral Resources, Technical University of Clausthal, 38678 Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany b School of Earth, Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK c Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS), 1359 Copenhagen, Denmark d Precambrian Geology and Geochronology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Makarova emb. 2, 199034 St Petersburg, Russia e Directorate of Geology and Mining, Ring Road 1, 492007 Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India f Department of Geology, Banaras Hindu University, 221005 Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India g Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada T6G 2E3 article info abstract Article history: Recently discovered diamondiferous kimberlite (Group-II) pipes in central India have surprisingly young Received 9 September 2009 40Ar/39Ar whole rock and U–Pb perovskite ages around 65 million years. These ages overlap with the main Received in revised form 1 December 2009 phase of the Deccan flood basalt magmatism, and suggest a common tectonomagmatic control for both flood Accepted 4 December 2009 basalts and kimberlites. The occurrence of macrodiamonds in the pipes implies the presence of a thick Available online 12 January 2010 subcratonic lithosphere at the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary, significantly different from the present-day Editor: R.W. Carlson thickness of the Indian lithosphere. -

List H - Igneous Rocks - Alphabetical List

LIST H - IGNEOUS ROCKS - ALPHABETICAL LIST Specific rock name Group name Specific rock name Group name A-type granites granites granodiorite porphyry granodiorites absarokite trachyandesites granophyre* igneous rocks adakites volcanic rocks granosyenite granites and syenites adamellite granites graphic granite granites agglutinates* pyroclastics green tuff pyroclastics agpaite syenites griquaite pyroxenite alaskite granites harzburgite peridotites albitite syenites hawaiite alkali basalts albitophyre keratophyre hornblendite ultramafics alkali olivine basalt alkali basalts hyaloclastite pyroclastics alnoite plutonic rocks I-type granites granites andesite porphyry andesites ignimbrite pyroclastics andesite tuff pyroclastics ijolite plutonic rocks ankaramite volcanic rocks jotunite plutonic rocks ankaratrite nephelinite kakortokite syenites anorthosite plutonic rocks kamafugite igneous rocks anorthositic gabbro gabbros keratophyre volcanic rocks aplite granites kersantite lamprophyres appinite plutonic rocks kimberlite* ariegite pyroxenite komatiite volcanic rocks ash-flow tuff pyroclastics labradoritite gabbros augitite volcanic rocks lamproite plutonic rocks basanite volcanic rocks latite volcanic rocks benmoreite volcanic rocks leucitite volcanic rocks biotite granite granites leucogranite granites boninite andesites lherzolite peridotites bostonite syenites limburgite volcanic rocks bronzitite pyroxenite liparite rhyolites camptonite lamprophyres liparite porphyry rhyolites charnockite granites lujavrite syenites chromitite ultramafics -

Some Industrial Mineral Deposit Models: Descriptive Deposit Models

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Some Industrial Mineral Deposit Models: Descriptive Deposit Models edited by G.J. Orris1 and J.D. Bliss1 Open-File Report 91-11A 1991 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. ____________________ 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Tucson, Arizona TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ................................................................. iii Descriptive model of diamond bearing kimberlite pipes (Model 12), by T.C. Michalski and P.J. Modreski ................................................................ 1 Descriptive model of wollastonite skarn (Model 18g) by G.J. Orris ................................................................. 7 Descriptive model of amorphous graphite (Model 18k) by D.M. Sutphin ........................................................... 9 Descriptive model of lithium in smectites of closed basins (Model 25lc) by Sigrid Asher-Bolinder ................ 11 Descriptive model of fumarolic sulfur (Model 25m) by K.R. Long ..............................................................… 13 Descriptive model of sedimentary zeolites; Deposit subtype: Zeolites in tuffs of open hydrologic systems (Model 25oa) by R.A. Sheppard ................................... 16 Descriptive model of sedimentary zeolites; Deposit subtype: -

Fluorine in Igneous Rocks and Minerals with Emphasis on Ultrapotassic Mafic and Ultramafic Magmas and Their Mantle Source Regions

MINERALOGICAL MAGAZINE VOLUME 60 NUMBER 399 APRIL 1996 Fluorine in igneous rocks and minerals with emphasis on ultrapotassic mafic and ultramafic magmas and their mantle source regions A. D. EDGAR, L. A. PIZZOLATO AND J. SHEEN Department of Earth Sciences, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada N6A 5B7 Abstract In reviewing the distribution of fluorine in igneous rocks it is clear that F abundance is related to alkalinity and to some extent to volatile contents. Two important F-bearing series are recognized: (1) the alkali basalt-ultrapotassic rocks in which F increases with increasing K20 and decreasing SiO2 contents; and (2) the alkali basalt-phonolite-rhyolite series with F showing positive correlation with both total alkalis and SiO2. Detailed studies of series (1) show that F abundance in ultrapotassic magmas (lamproite, kamafugite, lamprophyre) occurs in descending order in the sequence phlogopite>apatite>amphibole>glass. Fluorine contents in the same minerals from fresh and altered mantle xenoliths may be several orders of magnitude less than those in the host kamafugite. For many lamproites, F contents correlate with higher mg# suggesting that F is highest in the more primitive magmas. Experiments at mantle conditions (20 kbar, 900-1400~ on simplified F-bearing mineral systems containing phlogopite, apatite, K-richterite, and melt show that F is generally a compatible element. Additionally, low F abundance in minerals from mantle xenoliths suggests that F may not be available in mantle source regions and hence is unlikely to partition into the melt phase on partial melting. Melting experiments on the compositions of F-free and F-bearing model phlogopite harzburgite indicate that even small variations in F content produce melts similar in composition to those of lamproite.