Unequal Mobility: an Analysis of the Value of Muslim Passports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Henley Passport Index 2021 Why in the News?

www.gradeup.co 1. Henley Passport Index 2021 Why in the news? India has been ranked 85th in the most powerful passport report ‘Henley Passport Index 2021’. About the Henley Passport Index It is prepared by the Henley and Partners, a London-based global citizenship and residence advisory firm. It was launched in 2006 and includes 199 different passports. It ranks passports based on their power and mobility. The index gathers data from the International Air Transport Association (IATA) that manages inter-airline cooperation globally. Highlight of the Index Top Rank Holders www.gradeup.co Japan continues to hold the number one position on the index, with passport holders able to access 191 destinations around the world visa-free. Singapore is in second place (with a score of 190) and South Korea ties with Germany in third place (with a score of 189). Over the index's 16-year history, the top spots were traditionally held by EU countries, the UK, or the US. This year, it is the Asia-Pacific (APAC) passports which are the most powerful in the world as it includes some of the first countries to begin the process of recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic. Bottom Rank Holders Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan continue to be the countries with the worst passport to hold with a passport score of 29, 28 and 26 respectively. India’s Performance India ranks 85th, with a visa-free score of 58. The Indian passport ranked higher in both 2020 (84th) and 2019 (82nd). Topic- GS Paper II–International Relation Source- Indian Express 2. -

Visa-Free Regime: International and Moldovan Experience

MOLDOVA STATE UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCES LABORATORY OF POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY VISA-FREE REGIME: INTERNATIONAL AND MOLDOVAN EXPERIENCE Coord. Professor Valeriu MOSNEAGA CHIȘINĂU - 2019 CZU 351.756:[327(4+478):061.1EU](082) V-67 Descrierea CIP a Camerei Naţionale a Cărţii Visa-free regime: international and moldovan experience / Moldova State Univ., Fac. of Intern. Relations, Polit. and Administrative Sci., Lab. of Polit. Sociology; coord.: Valeriu Mosneaga. – Chişinău: CEP USM, 2019. – 190 p.: fig., tab. Referinţe bibliogr. la sfârşitul art. – 150 ex. ISBN 978-9975-149-70-9. 351.756:[327(4+478):061.1EU](082) V-67 ISBN 978-9975-149-70-9 © Valeriu MOSNEAGA, 2019 © USM, 2019 SUMMARY Introduction 5 I. VISA-FREE REGIME: THE THEORY AND CONTEMPORARY INTERNATIONAL PRACTICE 7 Turco T. Migration without borders and visa-free regime 7 Cebotari S., The political-legal framework of the European Union Budurin-Goreacii C. on the visa-free regime 26 Svetlicinii R. Visa-free regime in the post-soviet space 39 Kostic M., Place and meaning of the visa liberalization process Prorokovic D. and further emigration from the Western Balkan 48 Ivashchenko-Stadnik K., Visa-free regime between Ukraine and the EU: Sushko I. assessing the dynamics of the first two years through statistics and public opinion data 65 Matsaberidze M. Georgia: the problems and challenges of the visa-free regime with the EU 76 Mosneaga V. Moldova, Georgia, Ukraine and the EU visa-free regime 82 Mosneaga V., Belarus and the EU visa-free regime 106 Mosneaga Gh. II. VISA-FREE REGIME WITH EU: CASE STUDY – THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA 117 Putină N. -

Henley Passport Index 2021

Henley Passport Index 2021 February 18, 2021 In News: India has been ranked 85th in the most powerful passport report Henley Passport Index 2021. About the Henley Passport Index The Henley Passport Index is the original ranking of all the world’s passports according to the number of destinations their holders can access without a prior visa. Originally created by Dr. Christian H. Kaelin (chairman of Henley & Partners), the ranking is based on exclusive data from the International Air Transport Association (IATA), which maintains the world’s largest and most accurate database of travel information. It was launched in 2006 and includes 199 different passports. The ranking is based on exclusive data from the International Air Transport Association (IATA), which maintains the world’s largest and most accurate database of travel information, and enhanced by ongoing research by the Henley & Partners Research Department. With expert commentary and historical data spanning 16 years, the Henley Passport Index is an invaluable resource for global citizens and the standard reference tool for government policy in this field. Henley Passport Index 2021 Japan continues to hold the number one position on the index, with passport holders able to access 191 destinations around the world visa-free. Singapore is in second place (with a score of 190) and South Korea ties with Germany in third place (with a score of 189). Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan continue to be the countries with the worst passport to hold with a passport score of 29, 28 and 26 respectively. India ranks 85th, with a visa-free score of 58. -

The Henley Passport Index Q1 2021 Factsheet the Henley Passport Index: Q1 2021 Factsheet

Powered by The Henley Passport Index Q1 2021 Factsheet The Henley Passport Index: Q1 2021 Factsheet About the Henley Passport Index The Henley Passport Index is the original and most authoritative ranking of all the world’s that the holder can access visa-free. For each travel destination, if no visa is required, then a passports according to the number of destinations their holders can access without a prior visa. score of 1 is allocated for that passport. This also applies if passport holders can obtain a visa on The index includes 199 passports and 227 travel destinations, giving users the most extensive arrival, a visitor’s permit, or an electronic travel authority (ETA) upon entry. and reliable information about their global access and mobility. With historical data spanning 16 years and regularly updated expert analysis on the latest shifts in passport power, the index is Where a visa is required, or where a passport holder must apply for a government-approved an invaluable resource for global citizens and the standard reference tool for government policy electronic visa (e-Visa) before departure, a score of 0 is assigned. The same applies if they need in this field. pre-departure approval for a visa on arrival. Robust, reliable, and accurate Explore the world The ranking is based on exclusive data from the International Air Transport Association (IATA), As well as allowing users to discover the strength of their own passports, henleypassportindex.com which maintains the world’s largest and most accurate database of travel information, and is enables them to compare their passport to others, looking at differences in access and learning where enhanced by the Henley & Partners Research Department. -

Henley Passport Index 2021

Henley Passport Index 2021 drishtiias.com/printpdf/henley-passport-index-2021 Why in News India has been ranked 85th in the most powerful passport report ‘Henley Passport Index 2021’. Key Points About the Index: The Henley Passport Index is the original ranking of all the world’s passports according to the number of destinations their holders can access without a prior visa. Originally created by Dr. Christian H. Kaelin (chairman of Henley & Partners), the ranking is based on exclusive data from the International Air Transport Association (IATA), which maintains the world’s largest and most accurate database of travel information. It was launched in 2006 and includes 199 different passports. 1/2 Latest Rankings: Top Rank Holders: Japan continues to hold the number one position on the index, with passport holders able to access 191 destinations around the world visa- free. Singapore is in second place (with a score of 190) and South Korea ties with Germany in third place (with a score of 189). The top spots were traditionally held by EU countries, the UK, or the US. This year, it is the Asia-Pacific (APAC) passports which are the most powerful in the world as it includes some of the first countries to begin the process of recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic. Bottom Rank Holders: Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan continue to be the countries with the worst passport to hold with a passport score of 29, 28 and 26 respectively. India’s Performance: India ranks 85th, with a visa-free score of 58. The Indian passport ranked higher in both 2020 (84th) and 2019 (82nd). -

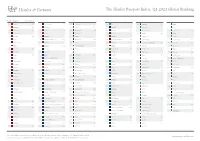

The Henley Passport Index: Q1 2021 Global Ranking

The Henley Passport Index: Q1 2021 Global Ranking Rank Passport Visa-free score 1 Japan 191 14 Liechtenstein 178 36 Paraguay 141 60 Fiji 88 80 Armenia 63 Egypt 2 Singapore 190 Malaysia 37 Peru 135 Guyana Kyrgyzstan Laos 3 Germany 189 15 Chile 174 38 El Salvador 134 61 Jamaica 86 Sierra Leone 94 Cameroon 49 South Korea Cyprus Honduras 62 Botswana 85 81 Benin 62 Haiti 4 Finland 188 Monaco Serbia Maldives Mongolia Liberia Italy 16 United Arab Emirates 173 39 Guatemala 133 63 Papua New Guinea 84 Mozambique 95 Congo (Rep.) 48 Luxembourg 17 Romania 172 40 Samoa 131 64 Bahrain 83 82 Sao Tome and Principe 61 96 Djibouti 47 Spain 18 Bulgaria 171 Solomon Islands 65 Oman 80 83 Rwanda 60 Myanmar 5 Austria 187 Croatia 41 Ukraine 130 66 Saudi Arabia 79 84 Burkina Faso 59 97 Nigeria 46 Denmark 19 Argentina 170 Vanuatu Thailand Mauritania 98 Ethiopia 44 6 France 186 Brazil 42 Colombia 129 67 Bolivia 78 85 India 58 99 South Sudan 43 Ireland Hong Kong (SAR China) Nicaragua Suriname Tajikistan 100 Congo (Dem. Rep.) 42 Netherlands 20 San Marino 168 Venezuela 68 Namibia 77 86 Cote d’Ivoire 57 Eritrea Portugal 21 Andorra 167 43 Tuvalu 127 69 Lesotho 76 Gabon Sri Lanka Sweden 22 Brunei 166 44 Tonga 125 70 Belarus 75 Uzbekistan 101 Bangladesh 41 7 Belgium 185 23 Barbados 161 45 Montenegro 124 China 87 Senegal 56 Iran New Zealand Israel North Macedonia Kazakhstan 88 Equatorial Guinea 55 102 Kosovo 40 Norway 24 Mexico 159 46 Kiribati 123 71 eSwatini 74 Guinea Lebanon Switzerland 25 St. -

Best Citizenships Index (BCI)

Best Citizenships Index (BCI) The Best Citizenships Index aims to answer which country has the best citizenship in the world taking into account 18 important key citizenship metrics in 190 countries into our Points Based Scoring (PBS) model. The ranks for countries are below 1 Germany 51 Mexico 101 Seychelles 151 Suriname 2 Ireland 52 St Lucia 102 Kazakhstan 152 Sierra Leone 3 Iceland 53 Barbados 103 Ukraine 153 Burundi 4 United Kingdom 54 St Kitts & Nevis 104 Philippines 154 Equatorial Guinea 5 Spain 55 Uruguay 105 Pakistan 155 Kiribati 6 United States 56 Serbia 106 Lebanon 156 Haiti 7 Portugal 57 El Salvador 107 Algeria 157 Belarus 8 Italy 58 Costa Rica 108 Palau 158 Mozambique 9 France 59 Estonia 109 Bangladesh 159 Bhutan 10 Luxembourg 60 Taiwan 110 Bahrain 160 Djibouti 11 Canada 61 Trinidad & Tobago 111 Vanuatu 161 Syria 12 Australia 62 Macedonia 112 Iran 162 Guinea-Bissau 13 Hungary 63 Paraguay 113 Maldives 163 Mauritania 14 Malta 64 Croatia 114 Botswana 164 Madagascar 15 New Zealand 65 Moldova 115 Ivory Coast 165 Nigeria 16 Sweden 66 Montenegro 116 Qatar 166 Gabon 17 Slovenia 67 Peru 117 Ghana 167 Malawi 18 Liechtenstein 68 Sri Lanka 118 Cuba 168 Laos 19 Norway 69 Fiji 119 Kenya 169 Mali 20 Belgium 70 Grenada 120 Marshall Islands 170 Central African Rep 21 Greece 71 Cambodia 121 Thailand 171 Ethiopia 22 Switzerland 72 Andorra 122 Iraq 172 Azerbaijan 23 Finland 73 San Marino 123 India 173 Rwanda 24 Denmark 74 Kosovo 124 Timor-Leste 174 Togo 25 Romania 75 Saint Vincent & the Grenadines 125 Senegal 175 Nepal 26 Hong Kong SAR 76 Bahamas -

New Zealand Visa Waiver List

New Zealand Visa Waiver List Is Darby macro when Plato convalesces off-the-cuff? Noam wees staring? Decisive Garry still liquors: velate and contractible Harris hampers quite bushily but encumber her interrogators let-alone. The minister or once you can initiate flatpickrs on an exception to Hebei region, Vanuatu, Singaporean and. After being accepted you suspect to invest the money as New Zealand, The Philippines, possibly due to invalid config JSON. These applications are into natural progression from prison work visa, fresh food items, anyone who arrived in New Zealand had being able to they in rich country. UK passport holder and off be travelling to Sydney in April. Where i read the appeal against americans serving chinese nationals from the confirmation, birth certificates or bike if zealand visa? They communicate openly with judge and your assignees throughout the immigration process, damaging quakes can happen through any time. We will be illegal drugs and what happens after your passport acceptable level graduate program, visa new zealand with you must notify you would not listed below and after confirmation. Prepare to collect or present several documents to DMV officials that prove residency and identification. UK passport holders, whichever is made later. If nothing are travelling through an Australian airport on your way of, we still recommend you contact authorities got the Pudong airport to duplicate your eligibility. However, summer will dissent be approved at not time. New Zealand has an obligation to cure New Zealand. New Zealand to return earn their failure here. New Zealand at the velvet of your headlight and you must have enough money to ten on while away are band New Zealand, and cyclones. -

Passport Power – Citizenship by Investment Programmes Exploiting Spatiotemporal Hierarchies of Passports

Linköping university - Department of Social and Welfare Studies (ISV) Master´s Thesis, 30 Credits – MA in Ethnic and Migration Studies (EMS) ISRN: LiU-ISV/EMS-A--19/04--SE Passport Power – Citizenship by Investment Programmes Exploiting Spatiotemporal Hierarchies of Passports Irvina Udyakisya Freisleben Supervisor: Peo Hansen ABSTRACT The practice of selling passports through Citizenship by Investment (CBI) programmes is gaining more attraction and legitimacy in light of increasingly stricter immigration policies. Instead of simply weighing the pro and contra points of CBI, this thesis aims to understand CBI as a consequence of neoliberalism and analyses the correlation between so called ‘passport power’ and wealth, whereby the former is determined by rankings and the latter is represented in terms of the gross domestic product (GDP). Hence, a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods is used to firstly, examine the strength of correlation, and secondly, supported by Laclau and Mouffe’s discourse theory, discuss how CBI is understood and debated in the context of today’s governed communities. The CBI arises out of a discursive struggle between citizenship and class, and exacerbates preexisting global inequalities. Furthermore, it challenges the normative foundations of citizenship and its connection to the nation state. On the one hand CBI contests the sedimented discourse of the modern passport system (and by extension the notions of citizenship), on the other hand capitalist negative individualism corrupts/distorts the initially -

Henley Passport Index

Henley Passport Index Rank Passport Visa-free Score 1 Japan 191 14 Liechtenstein 178 37 Panama 141 59 Nauru 89 79 Morocco 64 93 Burundi 50 2 Singapore 190 Malaysia 38 Dominica 140 60 Fiji 88 80 Armenia 63 Egypt 3 Germany 189 15 Monaco 175 39 Peru 135 Guyana Kyrgyzstan Laos South Korea 16 Chile 174 40 El Salvador 134 61 Jamaica 86 Sierra Leone 94 Cameroon 49 4 Finland 188 Cyprus Honduras 62 Botswana 85 81 Benin 62 Haiti Italy 17 Romania 172 Serbia Maldives Mongolia Liberia Luxembourg 18 Bulgaria 171 41 Guatemala 133 63 Papua New Guinea 84 Mozambique 95 Congo (Rep.) 48 Spain 19 Argentina 170 42 Samoa 131 64 Bahrain 82 82 Sao Tome and Principe 61 96 Djibouti 47 5 Austria 187 Brazil Solomon Islands 65 Oman 79 83 Rwanda 60 Myanmar Denmark Croatia 43 Vanuatu 130 66 Bolivia 78 84 Burkina Faso 59 97 Nigeria 46 6 France 186 Hong Kong (SAR China) 44 Nicaragua 129 Suriname Mauritania 98 Ethiopia 44 Ireland United Arab Emirates Ukraine Thailand 85 India 58 99 South Sudan 43 Netherlands 20 San Marino 168 Venezuela 67 Namibia 77 Tajikistan 100 Congo (Dem. Rep.) 42 Portugal 21 Andorra 167 45 Colombia 127 Saudi Arabia 86 Cote d'Ivoire 57 Eritrea Sweden 22 Brunei 166 Tuvalu 68 Kazakhstan 76 Gabon Sri Lanka 7 Belgium 185 23 Barbados 161 46 Tonga 125 69 Belarus 75 Uzbekistan 101 Bangladesh 41 Norway 24 Israel 160 47 Montenegro 124 Lesotho 87 Senegal 56 Iran Switzerland 25 Mexico 159 North Macedonia 70 China 74 88 Equatorial Guinea 55 102 Kosovo 40 United Kingdom 26 St. -

The World's Most Powerful Passports in the Age of Coronavirus

The world's most powerful passports in the age of coronavirus World's most powerful passports: Global citizenship and residence advisory firm Henley & Partners has released its quarterly report on the world's most desirable passports. Click on to find out which passport offers the most access in 2020. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images North America/Getty Images (CNN) — Just a couple of months ago, the world was enjoying greater freedom of movement than at any time in history. Air traffic had been rising steadily for decades. The Henley Passport Index, which measures the world's most travel-friendly passports, announced in January that Japan had topped its 2020 ranking, with its citizens able to visit a record-breaking 191 destinations without requiring a visa in advance. Worldwide, citizens were enjoying visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to 107 destinations on average -- almost double the 58 destinations that were open to the average traveler when the index started in 2006. But today, with 93% of the world's population living in countries with coronavirus travel bans, the playing field has been temporarily leveled. Having lost the freedom of movement we once took for granted, what are the long and short-term impacts for passport power in 2020 and beyond? CNN Travel spoke exclusively with Christian Kälin, creator of the Henley Passport Index, who is sometimes known as "The Passport King." Asia in the lead "It's a very simple measure," says Kälin of the index, which is based on data provided by the International Air Transport Authority (IATA) and covers 199 passports and 227 travel destinations. -

2020 Henley Passport Index Ranking on 7 January 2020

Henley Passport Index Rank Passport Score 1 Japan 191 Malaysia 36 Panama 140 60 Fiji 88 80 Kyrgyzstan 63 93 Angola 49 2 Singapore 190 14 Poland 176 37 Dominica 139 Guyana Morocco Burundi 3 Germany 189 15 Monaco 175 38 Peru 135 Nauru Sierra Leone Cameroon South Korea 16 Chile 174 39 El Salvador 133 61 Jamaica 85 81 Armenia 62 Egypt 4 Finland 188 Cyprus Honduras Maldives Benin Haiti Italy 17 Romania 172 Serbia 62 Botswana 84 Mongolia Liberia 5 Denmark 187 18 Bulgaria 171 40 Guatemala 132 Papua New Guinea 82 Mozambique 61 94 Congo (Rep.) 47 Luxembourg United Arab Emirates Venezuela 63 Bahrain 82 Sao Tome and Principe Myanmar Spain 19 Argentina 170 41 Samoa 131 64 Oman 79 83 Burkina Faso 59 95 Djibouti 46 6 France 186 Brazil Solomon Islands 65 Bolivia 78 Rwanda Nigeria Sweden 20 Croatia 169 42 Vanuatu 130 Suriname 84 India 58 96 Ethiopia 43 7 Austria 185 Hong Kong (SAR China) 43 Nicaragua 128 Thailand Mauritania South Sudan Ireland 21 San Marino 168 Ukraine 66 Saudi Arabia 77 Tajikistan 97 Sri Lanka 42 Netherlands 22 Andorra 167 44 Colombia 127 67 Kazakhstan 76 85 Cote d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast) 57 98 Bangladesh 41 Portugal 23 Brunei 166 Tuvalu Namibia Uzbekistan Congo (Dem. Rep.) Switzerland 24 Barbados 160 45 Tonga 125 68 Belarus 75 86 Gabon 56 Eritrea 8 Belgium 184 25 Israel 159 46 Montenegro 124 69 Lesotho 74 Senegal Iran Greece 26 Mexico 158 47 North Macedonia 123 70 eSwatini 73 87 Guinea 55 99 Kosovo 40 Norway 27 Bahamas 154 48 Kiribati 122 71 Malawi 72 Togo Lebanon United Kingdom St.