Appendix D the Lower Olentangy Watershed Inventory December 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ohiocontrolled Hunting

CONTROLLED HUNTING OHIO OPPORTUNITIES 2020-2021 Application period JULY 1, 2020 to JULY 31, 2020 OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WILDLIFE wildohio.gov OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WILDLIFE The Division of Wildlife’s mission is to conserve and improve fish and wildlife resources and their habitats for sustainable use and appreciation by all. VISIT US ON THE WEB WILDOHIO.GOV FOR GENERAL INFORMATION 1-800-WILDLIFE (1-800-945-3543) TO REPORT WILDLIFE VIOLATIONS 1-800-POACHER (1-800-762-2437) DIVISION OF WILDLIFE **AVAILABLE 24 HOURS** DISTRICT OFFICES OHIO GAME CHECK OHIOGAMECHECK.COM WILDLIFE DISTRICT ONE 1500 Dublin Road 1-877-TAG-IT-OH Columbus, OH 43215 (1-877-824-4864) (614) 644‑3925 WILDLIFE DISTRICT TWO HIP CERTIFICATION 952 Lima Avenue 1-877-HIP-OHIO Findlay, OH 45840 (1-877-447-6446) (419) 424‑5000 WILDLIFE DISTRICT THREE FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA 912 Portage Lakes Drive Akron, OH 44319 Like us on Facebook (330) 644‑2293 facebook.com/ohiodivisionofwildlife Follow us on Twitter WILDLIFE DISTRICT FOUR twitter.com/OhioDivWildlife 360 E. State Street Athens, OH 45701 (740) 589‑9930 WILDLIFE DISTRICT FIVE 1076 Old Springfield Pike Xenia, OH 45385 (937) 372‑9261 EQUAL OPPORTUNITY The Ohio Division of Wildlife offers equal opportunity regardless GOVERNOR, STATE OF OHIO of race, color, national origin, age, disability or sex (in education programs). If you believe you have been discriminated against in MIKE DeWINE any program, activity or facility, you should contact: The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Diversity & Civil Rights Programs-External Programs, DIRECTOR, OHIO DEPARTMENT 4040 N. -

February 2020

NEWSLETTER OF THE DELAWARE ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY Theflyer Volume 51 | Number 5 FEBRUARY 2020 Although the contents of the re- port confirmed many birders’ suspi- cions of a deeply troubled ecosys- IN THIS tem, the widening circle of aware- ness sparks a measure of hope. The same social media streams passing issue along the tragic news of three billion lost birds also contained many sug- GREETINGS FROM THE PRESIDENT ........... 1,3 FROM THE PRESIDENT Letter gestions for action alongside the MONTHLY MEETINGS ...................................... 2 hashtag #BringBirdsBack. Even DOS NEEDS YOU ............................................... 3 On September 19, the journal though I do not work in a lab or at a Science released a report entitled nature center, I had colleagues stop- UPCOMING FIELD TRIPS .................................. 4 “Decline of the North American Avi- ping me in the hallways to tell me GREAT BACKYARD BIRD COUNT .................... 4 fauna,” which documented a loss of how shocked they were to hear this MEMBERSHIP NEWS ........................................ 5 nearly one-third of all North Ameri- news, and what steps they were CONSERVATION SCIENCE GRANTS ............... 6 1 planning to take to help. can birds since 1970 . The report SORTING IT OUT - DE PUBLIC LANDS .......... 7 has been widely publicized by advo- One of seven actions promoted cacy organizations and research in the wake of the report includes HAWK WATCH REPORT ................................... 8 partners like American Bird Conserv- the directive to “Do Citizen Science”. FRONTIERS IN ORNITHOLOGY ....................... 9 ancy and The Cornell Lab of Orni- Indeed, citizen science efforts played thology, and even became the sub- a role in the creation of the report ject of a widely-shared op-ed in the itself -- observation data combined tions. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

For Delaware Run-Olentangy River HUC-12 (05060001 10 07)

Nine-Element Nonpoint Source Implementation Strategy (NPS-IS) for Delaware Run-Olentangy River HUC-12 (05060001 10 07) Prepared for: City of Delaware Prepared by: Civil & Environmental Consultants, Inc. Toledo, Ohio Version 1.0 Approved: June 29, 2021 This page intentionally left blank. Acknowledgements Version 1.0 prepared and written by: Deanna Bobak Civil & Environmental Consultants, Inc. 4841 Monroe Street, Suite 103 Toledo, OH 43623 Erin Wolfe Watershed & Sustainability Coordinator City of Delaware, Public Utilities Department 225 Cherry Street Delaware, OH 43015 with input from members of the Olentangy Watershed Alliance, including: • Chris Roshon, Preservation Parks • Jeff Kaufmann, Del-Co • Scott Stephens, Delaware Soil and Water Conservation District • Janelle Valdinger, City of Delaware • John Krygier, Ohio Wesleyan University • Laura Fay, Friends of the Lower Olentangy River • Heather Doherty, Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Scenic Rivers • Caroline Cicerchi, formerly of the City of Delaware The City of Delaware would like to acknowledge the collaboration of multiple partners in the preparation of this Nonpoint Source Implementation Strategy (NPS-IS) for the Delaware Run-Olentangy River HUC-12 (05060001 10 07). Thank you to the members of the Olentangy Watershed Alliance for providing financial and informational support in the planning process. The City of Delaware appreciates those individuals and organizations that contributed background information, insight into objectives and projects for inclusion in this NPS-IS. Thank you also to Rick Wilson, Ohio Environmental Protection Agency – Division of Surface Water, for guidance throughout the NPS-IS development process. This product or publication was financed in part or totally through a grant from the United States Environmental Protection Agency through an assistance agreement with the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency. -

08/19/2013 8:06 Am

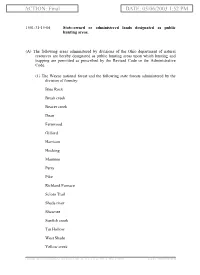

ACTION: Original DATE: 08/19/2013 8:06 AM TO BE RESCINDED 1501:31-15-04 State-owned or administered lands designated as public hunting areas. (A) The following areas administered by divisions of the Ohio department of natural resources are hereby designated as public hunting areas upon which hunting and trapping are permitted as prescribed by the Revised Code or the Administrative Code. (1) The following state forests administered by the division of forestry: Blue Rock Brush creek Beaver creek Dean Fernwood Gifford Harrison Hocking Maumee Perry Pike Richland Furnace Scioto Trail Shade river Shawnee Sunfish creek Tar Hollow West Shade [ stylesheet: rule.xsl 2.14, authoring tool: i4i 2.0 ras3 Jan 10, 2013 11:43, (dv: 0, p: 109458, pa: 189439, ra: 348825, d: 438920)] print date: 08/19/2013 09:05 PM 1501:31-15-04 TO BE RESCINDED 2 Yellow creek Zaleski *Mohican Memorial, except for the following described two-hundred-seventy-acre tract: Beginning at the intersection of the center line of route 97 and the west edge of the air strip, thence along the west edge of the air strip continuing in a straight line across Pine Run to a point on the ridge where a westerly line will intersect the west line of the Memorial forest west of Pine Run and about one-half mile south of route 97, thence north with the forest boundary to the middle of route 97, thence with said center line to the point of beginning. (2) The following lands owned, administered by or under agreement with the division of wildlife are hereby designated as public hunting areas or wildlife areas: Acadia cliffs Aldrich pond Ales run American Electric Power recreational area Aquilla lake Auburn marsh Avondale Bayshore fishing access Beach City Beaver creek (Greene county) Beaver (Marion county) **B & N Coal, Inc. -

Fort Delaware State Park New Castle County, Delaware

Historical Analysis and Map of Vegetation Communities, Land Covers, and Habitats of Fort Delaware State Park New Castle County, Delaware Lower Delaware River Watershed Submitted to: Delaware State Parks Delaware Division of State Parks 89 Kings Highway Dover, DE 19901 Completed by: Robert Coxe, Ecologist Delaware Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program Wildlife Section, Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control 4876 Hay Point Landing Road Smyrna, DE 19977 December 3, 2012 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction and Methods ............................................................................................. 4 Setting of Fort Delaware State Park ............................................................................................ 4 History and Formation of Fort Delaware State Park .................................................................. 6 Soils and Geology of Fort Delaware State Park ........................................................................ 6 Underlying Geology................................................................................................................ 6 Soils......................................................................................................................................... 6 Discussion of vegetation communities in general and why they are important in management 9 Discussion of Sea-Level Rise and why it may affect the vegetation communities at Fort Delaware State Park ................................................................................................................... -

Co-Hiker 15-08 V1

Central Ohio Hiking Club, YMCA of Central Ohio Volume 74, Issue 2 Summer 2015 The web: ymcacolumbus.org/hike email: [email protected] In This Issue … President ...................................................... John Troutman VP/Trail Master ........................................ Connie Sheridan Secretary ............................................................. Linda Coe Club News Treasurer ........................................................ Gerlinde Lott Membership ................................................... Kate Graham Hike Reports Special Events ............................................ Jeanne Barbee ! Findley State Park Historian ......................................................... Betty Bradley ! Inniswood Metro Park (Sr. Hike) Social Events ...................................................... Carol Beal ! Wolf Run Regional Park Webmaster ................................................... John Troutman ! Miami & Erie Canal Co-Hiker Editor .................................................. Jamie Abel ! M.L. Red Trabue Nature Preserve (Sr. Hike) ! Ash Cave/Cedar Falls State Park ! Narrows Preserve Park ! Slate Run Metro Park (Sr. Hike) ! Shallenberger/Rock Bridge Nature Preserves ! Delaware State Park ! Infirmary Mound Park Social Reports ! Corn Roast Tidbits from the Trail ! 10 Cool Trail Facts from AHS Report ! Two Types of Buckeye Trees in Ohio ! Puzzle destination: Hiking Quiz! At twenty-two, Cheryl Strayed (left) thought she had lost everything, so she made the most impulsive decision -

ACTION: Final DATE: 05/06/2003 1:52 PM

ACTION: Final DATE: 05/06/2003 1:52 PM 1501:31-15-04 State-owned or administered lands designated as public hunting areas. (A) The following areas administered by divisions of the Ohio department of natural resources are hereby designated as public hunting areas upon which hunting and trapping are permitted as prescribed by the Revised Code or the Administrative Code. (1) The Wayne national forest and the following state forests administered by the division of forestry: Blue Rock Brush creek Beaver creek Dean Fernwood Gifford Harrison Hocking Maumee Perry Pike Richland Furnace Scioto Trail Shade river Shawnee Sunfish creek Tar Hollow West Shade Yellow creek [ stylesheet: rule.xsl 2.13, authoring tool: i4i 1.409 Feb 7, 2002, (dv: 18, p: 8728, pa: 8379, ra: 39091, d: 35257)] print date: 05/06/2003 09:00 PM 1501:31-15-04 2 Zaleski *Mohican Memorial, except for the following described two-hundred-seventy-acre tract: Beginning at the intersection of the center line of route 97 and the west edge of the air strip, thence along the west edge of the air strip continuing in a straight line across Pine Run to a point on the ridge where a westerly line will intersect the west line of the Memorial forest west of Pine Run and about one-half mile south of route 97, thence north with the forest boundary to the middle of route 97, thence with said center line to the point of beginning. (2) The following lands owned, administered by or under agreement with the division of wildlife are hereby designated as public hunting areas or wildlife areas: Aldrich pond Ales run American Electric Power recreational area Aquilla lake Arcadia Cliffs Archbold Reservoir 01 Archbold Reservoir 02 Attica-Honey creek reservoir Auburn marsh Avondale Baird's concrete products Barnesville reservoir 1234 Battelle Darby Beach City Beaver creek (Columbiana county) Beaver creek (Greene County) 1501:31-15-04 3 Beaver Creek Reservoir Bellevue Reservoir 01 Bellevue Reservoir 02 Bellevue Reservoir 03 Bellevue Reservoir 04 Bellevue Reservoir 05 **B & N Coal, Inc. -

HISTORY of PENNSYLVANIA's STATE PARKS 1984 to 2015

i HISTORY OF PENNSYLVANIA'S STATE PARKS 1984 to 2015 By William C. Forrey Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Office of Parks and Forestry Bureau of State Parks Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Copyright © 2017 – 1st edition ii iii Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. vii CHAPTER I: The History of Pennsylvania Bureau of State Parks… 1980s ............................................................ 1 CHAPTER II: 1990s - State Parks 2000, 100th Anniversary, and Key 93 ............................................................. 13 CHAPTER III: 21st CENTURY - Growing Greener and State Park Improvements ............................................... 27 About the Author .............................................................................................................................................. 58 APPENDIX .......................................................................................................................................................... 60 TABLE 1: Pennsylvania State Parks Directors ................................................................................................ 61 TABLE 2: Department Leadership ................................................................................................................. -

Scouting in Ohio

Scouting Ohio! Sipp-O Lodge’s Where to Go Camping Guide Written and Published by Sipp-O Lodge #377 Buckeye Council, Inc. B.S.A. 2009 Introduction This book is provided as a reference source. The information herein should not be taken as the Gospel truth. Call ahead and obtain up-to-date information from the place you want to visit. Things change, nothing is guaranteed. All information and prices in this book were current as of the time of publication. If you find anything wrong with this book or want something added, tell us! Sipp-O Lodge Contact Information Mail: Sipp-O Lodge #377 c/o Buckeye Council, Inc. B.S.A. 2301 13th Street, NW Canton, Ohio 44708 Phone: 330.580.4272 800.589.9812 Fax: 330.580.4283 E-Mail: [email protected] [email protected] Homepage: http://www.buckeyecouncil.org/Order%20of%20the%20Arrow.htm Table of Contents Scout Camps Buckeye Council BSA Camps ............................................................ 1 Seven Ranges Scout Reservation ................................................ 1 Camp McKinley .......................................................................... 5 Camp Rodman ........................................................................... 9 Other Councils in Ohio .................................................................... 11 High Adventure Camps .................................................................... 14 Other Area Camps Buckeye .......................................................................................... 15 Pee-Wee ......................................................................................... -

CYSC Parent & Family Adventure Ideas

CYSC Parent & Family Adventure Ideas While your kids are at CYSC Day-Camp, we hope you take some time to explore and fall in love with our local communities as much as we have! Centerburg (>10 minutes South): - Heart of Ohio Trail: access point at Centerburg Park o Spans from Centerburg to Mount Vernon; offering close to 20 miles of walking trails with views of the Kokosing River and 19 bridges along the way - The Burg Cafe: 18 W Main St, Centerburg, OH 43011 o Hometown cafe owned by locals, with coffee and a small selection of food and baked goods - 1834 Midway Tavern: 29 N Clayton St, Centerburg, OH 43011 o Great local restaurant! Mount Vernon (~20 minutes North): - Honey Run Falls: 10855 Hazel Dell Road, Howard 43028 o Trails with view of Honey Run Falls and access to a gorge and Kokosing River - Ariel Foundation Park: 10 Pittsburgh Ave, Mt Vernon, OH 43050 o 250 acre park created on the site of a former glass making factory o It offers lakes, walking trails, observation tower, picnic areas, steel sculptures and architectural ruins - Wolf Run Park: 17621 Yauger Road Mount Vernon, OH 43050 o Nearly 10 miles of hiking trails, woodlands and a pond o Also includes a sheltered picnic area, dog park, and kids’ bouldering area - Downtown Mount Vernon (Main Street) o Town square full of coffee shops, restaurants, boutiques, antique shops, craft stores and local co-ops o Food & Coffee: - Stein Brewing Co. - North Main Cafe - Flappers Bar & Grille - Happy Bean Cafe - The Alcove - Everlasting Cup - R&M Southside Diner - Amato’s Woodfired Pizza -

Ohio 2013-14 Fishing Regulations

OHIOFishing Regulations 2013-2014 Effective MARCH 1, 2013 to FEBRUARY 28, 2014 MAY 4th & 5th ARE FREE FISHING DAYS On May 4 and 5, 2013, all Ohio residents are invited to take the opportunity to experience Ohio’s fantastic fishing without purchasing a fishing license. OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WILDLIFE • wildohio.com TABLE OF CONTENTS LICENSE FREE LICENSE Ohio residents born on or before LICENSE INFoRMAtIoN 2 REQUIREMENTS December 31, 1937 can obtain a free A fishing license is required to take fish, GENERAL INFoRMAtIoN 4 license at any license outlet, or online at frogs, or turtles from Ohio waters. wildohio.com. StAtEWIDE REGULAtIoNS 5 Persons fishing in privately owned The following Ohio residents are also oHIo RIVER REGULAtIoNS 6 ponds, lakes, or reservoirs to and from eligible for a free license, but must which fish do not migrate, are not re- submit a formal application (Form DNR MAUMEE, PoRtAGE, MAHoNING, & SANDUSkY RIVER REGS 7 quired to have a license to take fish, but 9032), which is available by calling SPECIFIC WAtER & SItE REGULAtIoNS 8 must have one to take frogs or turtles. 1-800-WILDLIFE (1-800-945-3543): Persons fishing in privately owned LAkE ERIE & ItS tRIBUtARIES REGULAtIoNS 10 Persons who are mobility impaired ponds, lakes, or reservoirs that are open and require the assistance of an- PYMAtUNING LAkE REGULAtIoNS 11 to public fishing through an agreement other person to cast and retrieve or lease with the Division of Wildlife are Holders of “Veteran” license plates FRoG & tURtLE REGULAtIoNS 11 required to have a fishing license.