The Iowa State Fair Art Salon, 1854-1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1 0-Cover.P65 the CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART

ANNUAL REPORT 2002 THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART REPORT 2002 ANNUAL 0-Cover.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:08 PM THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1-Welcome-A.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:16 PM Feathered Panel. Peru, The Cleveland Narrative: Gregory Photography credits: Brichford: pp. 7 (left, Far South Coast, Pampa Museum of Art M. Donley Works of art in the both), 9 (top), 11 Ocoña; AD 600–900; 11150 East Boulevard Editing: Barbara J. collection were photo- (bottom), 34 (left), 39 Cleveland, Ohio Bradley and graphed by museum (top), 61, 63, 64, 68, Papagayo macaw feathers 44106–1797 photographers 79, 88 (left), 92; knotted onto string and Kathleen Mills Copyright © 2003 Howard Agriesti and Rodney L. Brown: p. stitched to cotton plain- Design: Thomas H. Gary Kirchenbauer 82 (left) © 2002; Philip The Cleveland Barnard III weave cloth, camelid fiber Museum of Art and are copyright Brutz: pp. 9 (left), 88 Production: Charles by the Cleveland (top), 89 (all), 96; plain-weave upper tape; All rights reserved. 81.3 x 223.5 cm; Andrew R. Szabla Museum of Art. The Gregory M. Donley: No portion of this works of art them- front cover, pp. 4, 6 and Martha Holden Jennings publication may be Printing: Great Lakes Lithograph selves may also be (both), 7 (bottom), 8 Fund 2002.93 reproduced in any protected by copy- (bottom), 13 (both), form whatsoever The type is Adobe Front cover and frontispiece: right in the United 31, 32, 34 (bottom), 36 without the prior Palatino and States of America or (bottom), 41, 45 (top), As the sun went down, the written permission Bitstream Futura abroad and may not 60, 62, 71, 77, 83 (left), lights came up: on of the Cleveland adapted for this be reproduced in any 85 (right, center), 91; September 11, the facade Museum of Art. -

John Steuart Curry and the Kansas Mural Controversy and Grant Wood: a Study in American Art and Culture

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1988 Review of Rethinking Regionalism: John Steuart Curry and the Kansas Mural Controversy and Grant Wood: A Study in American Art and Culture. Richard W. Etulain University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Etulain, Richard W., "Review of Rethinking Regionalism: John Steuart Curry and the Kansas Mural Controversy and Grant Wood: A Study in American Art and Culture." (1988). Great Plains Quarterly. 360. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/360 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 234 GREAT PLAINS QUARTERLY, FALL 1988 statehouse in Topeka. Emphasizing the details of Curry's life and how they interlocked with national, historical, and political happenings between 1937 and 1942, Kendall focuses par ticularly on the ideological and cultural atti tudes that embroiled Curry, newspaper editors, and thousands of Kansans in the mural contro versy. Most of this smoothly written and adequately illustrated study centers on the cultural back grounds of the Coronado and John Brown panels in the Kansas murals, with less analysis of other sections and details. Placing her art history at the vortex of popular culture, the author pro vides revealing insights into the varied milieus of the 1930s, Curry's intellectual backgrounds, and Kansas history and experience that caused the debate. -

Curry, John Steuart American, 1897 - 1946

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 Curry, John Steuart American, 1897 - 1946 Peter A. Juley & Son, John Steuart Curry Seated in Front of "State Fair," Westport, Connecticut, 1928, photograph, Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum BIOGRAPHY John Steuart Curry was one of the three major practitioners of American regionalist painting, along with Thomas Hart Benton (American, 1889 - 1975) and Grant Wood (American, 1891 - 1942). Curry was born on a farm near Dunavant, Kansas, on November 14, 1897. His parents had traveled to Europe on their honeymoon, and his mother, Margaret, returned with prints of European masterworks that hung on the walls of the family home. She enrolled her son in art lessons at a young age, and his family supported his decision to drop out of high school in 1916 to study art. Curry worked for the Missouri Pacific Railroad and attended the Kansas City Art Institute for a month before moving to Chicago, where he studied at the Art Institute for two years. In 1918 he enrolled at Geneva College in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania. Curry decided to pursue commercial illustration, and in 1919 he began to study with illustrator Harvey Dunn in Tenafly, New Jersey. From 1921 to 1926, Curry’s illustrations appeared in publications such as the Saturday Evening Post and Boy’s Life. In 1923, while living in New York City, he married Clara Derrick; shortly thereafter he bought a studio at Otter Ponds near the art colony in Westport, Connecticut. In 1926 Curry stopped producing illustrations and left for Paris, where he took classes in drawing with the Russian teacher Vasili Shukhaev and studied old master paintings at the Louvre. -

BIOGRAPHIES John Antrobus

BIOGRAPHIES John Antrobus (1837–1907): Sculptor and painter of portraits, landscapes, and genre scenes (showing everyday life). Antrobus was born in England but came to Philadelphia in 1850. During his travels through the American West and Mexico, he worked as a portraitist before opening a studio in New Orleans. He served briefly with the Confederate Army during the Civil War before moving to Chicago. Antrobus sculpted both Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas and was the first artist to paint a portrait of Ulysses S. Grant (in 1863). Edward Atkinson (1827–1905): American political leader and economist who began his political career as a Republican supporter of the Free Soil movement. Atkinson fought slavery before the Civil War by helping escaped slaves and raising money for John Brown. After the Civil War, in 1886, Atkinson campaigned for future President Grover Cleveland and worked against imperialism (the movement to expand a nation’s territorial rule by annexing territory outside of the main country) after the Spanish-American War. Baker & Co (active, 19th century): Lithography firm associated with Louis Kurz. Thomas Ball (1819–1911): American sculptor who gained recognition for his small busts before creating more monumental sculptures. Notable works include one of the first statues portraying Abraham Lincoln as the Great Emancipator (1876), paid for by donations from freed slaves and African American Union veterans, which stands in Washington D.C.’s Lincoln Park. Ball also created a heroic equestrian statue of George Washington for the Boston Public Garden (1860–1864). He joined an expatriate community in Italy, where he received many commissions for portrait busts, cemetery memorials, and heroic bronze statues. -

MISSOURI ART,ARTISTS, and ARTIFACTS

MISSOURI ART,ARTISTS, And ARTIFACTS A Fourth Grade Social Studies Curricular Tour A Docent Guide to Selected Works from The Museum of Art and Archaeology University of Missouri-Columbia *Not all images are on display in the Museum* 2 Museum of Art and Archaeology University of Missouri-Columbia 1 Pickard Hall Columbia, MO 65211 Phone: 573-882-3591 Fax: 573-884-4039 Website http:/maa.missouri.edu/ Museum Hours Tuesday – Friday: 9 a.m. – 4 p.m. Saturday – Sunday: Noon – 4 p.m. Closed Mondays, University of Missouri-Columbia Holidays, and Christmas Day through New Year’s Day Admission is FREE and open to the public. The Museum is ADA accessible. The Museum is a member of AAM – American Association of Museums. 3 MISSOURI ART, ARTISTS, & ARTIFACTS A Fourth Grade Social Studies Curricular Tour Works from the Museum’s permanent collection along with items and works from relevant exhibitions have been organized into a resource book for a Docent tour focusing on Missouri Grade-Level Expectations for Fourth Grade Social Studies. What’s included in this guide? This guide includes images of the relevant art works for this tour. Teaching information includes detailed descriptions of the objects, background about their historical context, and discussions of their iconography (symbolic importance), as well as questions designed to encourage students to look more closely at the work of art and to share their responses. Tour Overview Students step back in time when they walk through the doors of the Museum of Art and Archaeology to take part in the Fourth Grade Curricular Tour. -

Review of John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood: a Portrait of Rural America by Joseph S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Winter 1985 Review of John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood: A Portrait of Rural America By Joseph S. Czestochowski Robert Spence University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Spence, Robert, "Review of John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood: A Portrait of Rural America By Joseph S. Czestochowski" (1985). Great Plains Quarterly. 1821. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1821 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 70 GREAT PLAINS QUARTERLY, WINTER 1985 John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood: A Portrait tive" (p. 12). But a three-legged stool stands of Rural America. By Joseph S. Czestochow uncertainly on two legs, and Mr. Czestochowski ski. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, is impelled to lay in some underpinning by 1981. Photographs, illustrations, notes, bib citing Benton continuously and by including as liography, index. 224 pp. $32.00. an Afterword (pp. 213-17) his autobiographical reflections "On Regionalism." This catalogue was assembled to coincide with Other underpinning, in the consolidation of an exhibition of "the best works" (p. 5) of two the text portion of the volume, is comprised of our most famous American scene painters, of a perceptive analysis by Sue Kendall (pp. -

Press Release

! ! STUART DAVIS The Punk Monk returns with Music for Mortals out August 7, 2012 North American Tour Dates Announced Stuart Davis hasn't quit his day job. He's still a full-time performing songwriter. Davis, a practicing Buddhist monk, is just a bit more hyphenated these days; he's become a Musician- Director-Comedian-Author. With 15 albums to his credit and guest appearances on NPR and syndicated radio's "Coast to Coast Live," music is still his main squeeze, and his irreverent TV show, Sex God, Rock ‘n Roll brought Stuart’s down to earth wit and irreverent humor – a mainstay of his live shows – to a larger audience. His latest release, Music For Mortals, out August 7 on SDM, is proof; the melodies are catchy and instantly memorable, intelligent songwriting in the vein of Joe Jackson, Elvis Costello, XTC, and - being a Minnesota native - Bob Dylan. The first single, "Beautiful Place," has thought-provoking lyrics and builds to a soaring, instantly memorable chorus you’ll have a hard time getting out of your head, and USA Today just selected "Not Another Lifetime" for their Playlist, saying, "the versatile, sonically inventive singer/songwriter is at his most wickedly playful on this track from Music for Mortals.” The album was funded by fans from 15 countries, who put up over $80,000, to see the project come to life, and then waited two years for it to be completed. "It was astonishing, this outpouring of support from around the world," he says. Their enthusiasm was contagious, because the new music finds Davis more on fire than ever. -

AMERICAN PAINTING 1910-1940 Frye Art Museum

INTRODUCTION TO ART HISTORY: AMERICAN PAINTING 1910-1940 Frye Art Museum Instructor: Rebecca Albiani DATES: July 28-31, 2009, 10:15 am-12:45 pm PREREQUISITES: None NUMBER OF CREDITS OR CEU’s: One credit or 10 clock hours COURSE DESCRIPTION: An introductory class designed to introduce the major trends in American painting from about 1910 to 1940. This course will discuss the impact of European modernism on the American art scene in the early years of the 20th century and the efforts made by many artists in the U.S. to be both “American” and “modern.” Furthermore, we will examine the impact of major social forces – the Great War, increasing urbanization and industry, the Jazz Age, the Great Depression – on art- making in America. COURSE OBJECTIVES: The participant will acquire a vocabulary for discussing early 20th century painting. The participant will gain a basic familiarity with a number of artistic movements including the Ashcan School, Cubism, Futurism, Precisionism, Regionalism, and Social Realism. With a heightened understanding of the social forces that shaped this art, the participant will be well positioned to use this fall’s “American Modernism” exhibition at the Frye Art Museum as a tool in his or her own teaching. STUDENT EXPECTATIONS: 1. Attend all sessions 2. Participate in discussions as appropriate 3. For credit, research one artistic development and present this research in written form INSTRUCTOR: Rebecca Albiani, formerly a Ph.D. candidate in Renaissance art history, received her M.A. from Stanford University and her B.A. from U.C. Berkeley. She has taught aesthetics and introductory art history courses covering from ancient Egypt to the 20th century. -

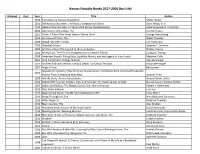

Kansas Notable Books 2017-2006 (By Title)

Kansas Notable Books 2017-2006 (by title) Ordered Cost Year Title Author 2012 8 Wonders of Kansas! Guidebook Marci Penner 2015 999 Kansas Characters : Ad Astra, a Biographical Series Dave Webb, et al 2010 Addie of the Flint Hills: A Prairie Child During the Depression Adaline Sorace, D. Prutzman 2013 Adventures of Beanboy, The Lisa Harkrader 2007 Afoot: A Tale of the Great Dakota Turkey Drive George Brandsberg 2012 Afterlives of Trees, The Wyatt Townley 2006 Airball: My Life in Briefs L.D. Harkrader 2016 Alphabet School Stephen T. Johnson 2009 Amelia Earhart: The Legend of the Lost Aviator Shelley Tanaka 2012 Amelia Lost: The Life and Disappearance of Amelia Earhart Candace Fleming 2008 American Shaolin: Flying Kicks, Buddhist Monks, and the Legend of Iron Crotch Matthew Polly 2011 Amy Barickman's Vintage Notions Amy Barickman 2011 And Hell Followed With It: Life and Death in a Kansas Tornado Bonar Menninger 2007 Angle of Yaw Ben Lerner Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality 2011 Empire That Civilized the Wild West Stepher Fried 2009 Artfully Done : Across Generations Roxann Banks Dicker 2011 Baking With Friends: Recipes, Tips, and Fun Facts for Teaching Kids to Bake Sharon Davis, Charlene Patton 2007 Ballots and Bullets: The Bloody County Seat Wars of Kansas Robert K. DeArment 2012 Bent Road: A Novel Lori Roy 2013 Beyond Cold blood: The KBI from Ma Barker to BTK Larry Welch 2014 Biting Through the Skin Nina Mukerjee Furstenau 2016 Bitter Magic, A Roderick Townley 2014 Black Country, The -

“BY POPULAR DEMAND”: the HERO in AMERICAN ART, C. 1929-1945

“BY POPULAR DEMAND”: THE HERO IN AMERICAN ART, c. 1929-1945 By ©2011 LARA SUSAN KUYKENDALL Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Charles C. Eldredge, Ph.D. ________________________________ David Cateforis, Ph.D. ________________________________ Marni Kessler, Ph.D. ________________________________ Chuck Berg, Ph.D. ________________________________ Cheryl Lester, Ph.D. Date Defended: April 11, 2011 The Dissertation Committee for LARA SUSAN KUYKENDALL certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “BY POPULAR DEMAND”: THE HERO IN AMERICAN ART, c. 1929-1945 ________________________________ Chairperson Charles C. Eldredge, Ph.D. Date approved: April 11, 2011 ii Abstract During the 1930s and 1940s, as the United States weathered the Great Depression, World War II, and dramatic social changes, heroes were sought out and created as part of an ever-changing national culture. American artists responded to the widespread desire for heroic imagery by creating icons of leadership and fortitude. Heroes took the form of political leaders, unionized workers, farmers, folk icons, historical characters, mothers, and women workers. The ideas they manifest are as varied as the styles and motivations of the artists who developed them. This dissertation contextualizes works by such artists as Florine Stettheimer, Philip Evergood, John Steuart Curry, Palmer Hayden, Dorothea Lange, Norman Rockwell, and Aaron Douglas, delving into the realms of politics, labor, gender, and race. The images considered fulfilled national (and often personal) needs for pride, confidence, and hope during these tumultuous decades, and this project is the first to consider the hero in American art as a sustained modernist visual trope. -

View the Presentation

Annelise K. Madsen | Art Institute of Chicago | 29 Oct 2016 “Something of color and imagination”: Grant Wood, Storytelling, and the Past’s Appeal in Depression-Era America Grant Wood, Parson Weems’ Fable, 1939, oil on canvas. Amon Carter Museum of American Art. 2 New York Times, January 3, 1940, p. 18. 3 Grant Wood, Parson Weems’ Fable, 1939, oil on canvas. Amon Carter Museum of American Art. 4 Gilbert Stuart, George Washington (The Athenaeum Portrait), 1796, oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; owned jointly with Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 5 Grant Wood, Parson Weems’ Fable, 1939, oil on canvas. Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Grant Wood with Parson Weems’ Fable on easel, 1939. Figge Art Museum Grant Wood Digital 6 Collection, scrapbook 8, University of Iowa Libraries. John Steuart Curry, The Oklahoma Land Rush, April 22, 1889, 1938. Department of Interior Building, Washington, D.C. Charles Goodwin, Fragment of Shaker Hall Rug, c. 1937, watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink. 7 National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Index of American Design. Grant Wood, Daughters of Revolution, 1932, oil on Masonite. Cincinnati Art Museum. 8 Grant Wood, Daughters of Revolution, 1932, oil on Masonite. Cincinnati Art Museum. Grant Wood (designer); Emil Frei Art Glass Company, Munich, Germany (fabricator), Memorial 9 Window, 1928–29, stained glass. Veterans Memorial Building, Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851, oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 10 Grant Wood, Daughters of Revolution, 1932, oil on Masonite. Cincinnati Art Museum. Grant Wood, Daughters of Revolution, 1932, oil on Masonite. -

Beach Museum of Art Exhibition Explores John Steuart Curry's Fascination with the American West

9/17/2019 Beach Museum of Art exhibition explores John Steuart Curry's fascination with the American West K-State home » DCM » K-State News » News » Beach Museum of Art exhibition explores John Steuart Curry's fascination with the American West K-State News A cowboy at heart: Beach Museum of Art exhibition explores John Steuart Curry's fascination with the American West Tuesday, Sept. 17, 2019 "The Code of the West," a 20-by-40-inch oil on canvas by John Steuart Curry from 1923, is featured in the exhibition "John Steuart Curry: The Cowboy Within" opening Sept. 24 at Kansas State University's Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art. Curry created the illustration for author Zane Grey's serialized story "The Code of the West," featured in the July 7, 1923, edition of The Country Gentleman. The work was a gift to the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas by Mrs. Ben Hibbs in memory of her husband. | Download this photo. (/media/images/sept19/code_of_the_west.jpg) MANHATTAN — One of the most noted artists to come from Kansas will be featured in a first-of-its-kind exhibition at the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art (https://beach.k-state.edu/) at Kansas State University. Using drawings, paintings, magazines and books from the Beach Museum of Art's collection and from several lenders, "John Steuart Curry: The Cowboy Within" is the first exhibition to survey Curry's vision of the American West. The exhibition opens Tuesday, Sept. 24, and runs through March 21, 2020, in the museum's Marion Pelton Gallery.