Weisgall Linernts 9425.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elektra at San Francisco Opera Encore

Turandot 2017 cover.qxp_Layout 1 8/23/17 9:17 AM Page 1 2017–18 SEASON GIACOMO PUCCINI WHO YOU WORK WITH MATTERS Consistently ranked one of the top 25 producers at Sotheby’s International Realty nationally, Neill Bassi has sold over $133 million in San Francisco this year. SELECT 2017 SALES Address Sale Price % of Asking Representation 3540 Jackson Street* $15,000,000 100% Buyer 3515 Pacific Avenue $10,350,000 150% Seller 3383 Pacific Avenue $10,225,000 85% Buyer 1070 Green Street #1501 $7,500,000 101% Seller 89 Belgrave Avenue* $7,500,000 100% Seller 1164 Fulton Street $7,350,000 101% Seller 2545-2547 Lyon Street* $6,980,000 103% Seller 3041 Divisadero Street $5,740,000 118% Seller 2424 Buchanan Street $5,650,000 94% Buyer 3984 20th Street $4,998,000 108% Seller 1513 Cole Street $4,250,000 108% Seller 1645 Pacific Avenue #4G* $2,750,000 97% Buyer *Sold off market NOW ACCEPTING SPRING 2018 LISTINGS Request a confidential valuation to find out how much your home might yield when marketed by Neill Bassi and Sotheby’s International Realty. NEILL BASSI Associate Broker 415.296.2233 [email protected] | neillbassi.com “Alamo Square Victorian Sale CalBRE#1883478 Breaks Neighborhood Record” Sotheby’s International Realty and the Sotheby’s International Realty logo are registered (or unregistered) service marks used with permission. Operated by Sotheby’s International Realty, CURBED Inc. Real estate agents affiliated with Sotheby’s International Realty, Inc. are independent contractor sales associates and are not employees of Sotheby’s International Realty, Inc. -

1 Cultual Analysis and Post-Tonal Music

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-02843-1 - Gendering Musical Modernism: The Music of Ruth Crawford, Marion Bauer, and Miriam Gideon Ellie M. Hisama Excerpt More information 1 CULTUAL ANALYSIS AND POST-TONAL MUSIC Given the vast, marvelous repertoire of feminist approaches to literary analysis introduced over the past two decades, a music theorist interested in bringing femi- nist thought to a project of analyzing music by women might do well to look first to literary theory. One potentially useful study is Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s landmark work The Madwoman in the Attic, which asserts that nineteenth-century writing by women constitutes a literary tradition separate and distinct from the writing of men and argues more specifically that writings of women, including Austen, Shelley, and Dickinson, share common themes of alienation and enclo- sure.1 Some feminist theorists have claimed that a distinctive female tradition exists also in modernist literature; Jan Montefiore, for example, asserts that in autobio- graphical writings of the 1930s, male modernists tended to portray their experi- ences as universal in contrast to female modernists who tended to represent their experiences as marginal.2 But because of the singular nature of the modernist, post-tonal musical idiom, an analytical project intended to explore whether a distinctive female tradition indeed exists in music immediately runs aground. Unlike tonal compositions, which draw their structural principles from a more or less unified compositional language, post- tonal works are constructed according to highly individualized schemes whose meaning and coherence derive from their internal structure rather than from their relation to a body of works. -

April 2008 in This Issue

The Sacred in Opera April 2008 In this Issue... Ruth Dobson For the next two editions of the SIO newsletter, we are taking an in-depth look at one-act Christmas operas which can be easily produced and are appropriate for both children and adults. This issue we will profile Amahl and the Night Visitors, Only a Miracle, St. Nicholas, Good King Wenceslas, and The Shepherd’s Play. The next issue will highlight The Christmas Rose, The Greenfield Christmas Tree, The Finding of the King, The Night of the Star, and others. Thanks to Allen Henderson for sharing his insight into a triology of operas by Richard Shephard, Good King Wenceslas, The Shepherd’s Play, and St. Nicholas, with us in this issue. As great as Amahl and the Night Visitors is, there are these and other works waiting to be discovered by all of us. We hope you will find these suggestions interesting. These operas vary in length from 10 minutes to an hour, and can be presented alone or paired with others. Amahl and the Night Visitors is almost always a successful box office draw. Pairing it with a lesser known work could make for a very enjoyable afternoon or evening presentation and give audiences an opportunity to enjoy other equally wonderful works. Several of these operas use children as cast members, while others call for only adult performers, but all have stories appropriate for children. They are written in a variety of styles and have very different production requirements. Producers would need to take into consideration the ages of the children that are the target audience. -

"Propheten" Von Kurt Weill

((Prophetenn von Kurt Weill Ende 1935 erschien in New York im Verlag «Viking Hau se» << The Eternal Road », Ludwig Lewisohns sorgfältige Überset zung von «Der Weg der Verheißung», für die man einen griffi geren und «verkaufbareren » Titel al s «The Road of Promi se» gewählt hatte. Im Vorwort dieses Buches wurde die Urauffüh rung vo n Werfels «Drama » (bzw. «Bibelspiel », wie noch auf dem ersten Manuskript zu lesen war) in Lewisohns Überset zung angekündigt, und zwar für Jänner 1936 im Manhattan Opera Hau se in einer Inszenierung von Max Reinhardt. Nur wen ige Tage vor der geplanten Premiere meldeten die Produzenten Konkurs an . Reinhardt reiste nach Hollywood ab, und Werfel kehrte nach Europa zurück. Genau ein Jahr später - am 4. Jänner 1937 - und in Abwesenheit von Werfel brach te Reinhardt eine vielfach veränderte Version von «Th e Eternal Road » am selben Schauplatz in Manhattan heraus, begleitet von einem gigantischen Werbefeldzug und unter al lgemeinem Beifall von Presse und Publikum. Schon im September 1935 hatte Reinhardt über erbarmungs losen Kürzungen eines Dramas gesessen, das über sechs Stunden dauern sollte, wobei mindestens 3 '/, Stunden Musik erklungen wären . Angeblich wegen dieser ungeheuren Länge, aber auch aus Gründen der Zweckdienlichkeit strich Reinhardt fa st den ganzen vierten und letzten Akt. in dem Weill derart von dem Stoff gefangen genommen worden war, daß er - wiewohl in großer Zeitnot - sogar noch jene Stel len vertonte, die von Werfel als Sprechtexte konzipiert worden waren . Werfel hatte den IV. Akt ursprünglich mit «Propheten » über• schrieben, nicht «Die Propheten », aber aus unbekanntem Grund hatte Lewisohn diesen unspezifischen Titel mit «The Proph ets» übersetzt und damit auf mißverständliche Weise auf die ganze Reihe von Propheten und Heiligen angespielt, die in den hebräischen Königreichen Palästinas vom 8. -

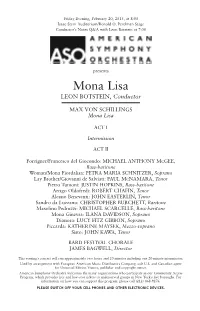

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

From "Regina" to "Juno" Indeed They Also Are in the Weill- Brecht Operas

82 MID-MONTH RECORDINGS villainy. Also, through the Kurt Weill- Bert Brecht operas, its preoccupation with verbal values. Nevertheless, Puccini is around, and Montemezzi and Alfano and Wolf-Ferrari too, as From "Regina" to "Juno" indeed they also are in the Weill- Brecht operas. They show up here in the wide By VIRGIL THOMSON and thoroughly (quite relentlessly, ranges of the vocal lines and in their indeed) Irish of cast. But for all their way of constantly working all over AEC BLITZSTEIN, a maj or con stylistic adherence to the play's back those ranges. There is little of the tributor to the English-singing ground they sound to this listener metrical cantilena in arias and still M stage (American branch), is more earth-bound than earthy. Their less of the psalm-like patter in reci both composer and word-author of performance, moreover, both by the tative that English texts invite. There two recent Columbia releases. These actors who do not really sing, like is indeed almost no recitative or aria consist of the musical numbers that Shirley Booth and Melvyn Douglas, writing in the classical sense. There framed and ornamented a play-with- and by those who do (though not in is chiefly a treatment of the text's music version of Sean O'Casey's the Irish manner) like Jack Mac- rhymed prose through a special spe "Juno and the Paycock," recently Gowran, Monte Amundsen, and Loren cies of arioso, a declamatory setting visible on Broa^vay under the title Driscoll, is nowhere air-borne by any of words and phrases that moves, in of "Juno," (Cclu5n.>ia mono OL 5380, Hibernian afflatus. -

Lavender Hill "Serious Competition for 'GUYS AND

On Wifely Constancy The Passing Show Miss Cornell Poetic Speaks Playwrights Of Those She Go on Plays Right Writing Star of Maugham Revival Sees Lesson in Classic Hits Way Is Hard and Rewards Fewer, By Mark Barron But, Like Anouilh, They Work On NEW YORK. [sake, just because it was a great A veteran from in the * By Jay Carmody trouper coast play past. to coast, Miss Katharine Cornell “It is just as Maugham writes The is that so sensitive surprise many humans go on writing in ‘The Constant Wife’ when I for the theater. was still traveling the other eve- am fighting to hold my husband The insensitive ones, no. are ning after her They gamblers, betting that their Broadway premiere from a beautiful blond who is al- literal reports on life or their broad jokes about will catch the it, in W. Somerset Maugham’s artful most stealing him from me.’’ she public fancy and make them rich. They know the odds and the comedy, "The Constant Wife.” said. consequences involved in failure and nature armed them with the This “As the wife in Maugham’s toughness to both. These are time, however, Miss Cor- play, accept the addicts and there is I am faced with nell took only a hop-skip-and- the realization little need to give them a second thought. that Jump from National every marriage needs a great It is different with the other, smaller group. They are crea- Broadway’s Theater to her deal more thought than most tive, artistic and idealistic. They write plays because they want long-established home on Manhattan’s East wives devote to it. -

Topical Weill: News and Events

Volume 15 Number 2 topical Weill Fall 1997 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news &news events Mark your calendars—18 October 1998 is Lenya’s 100th Birthday! &news events Publications CD features the legendary Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch of Cologne will publish recordings that Lenya the German edition of Speak Low (When You Speak made for Philips in Ham- Love): The Letters of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya in the burg in 1955 and 1956, and fall of 1998. Entrusted to editors and translators Kim the booklet includes never- H. Kowalke and Lys Symonette by Lenya on her before-published photos of deathbed in 1981, these letters are testimonies to one of the recording sessions. the century’s most legendary artistic partnerships. The Lenya’s performances are German version contains minor revisions along with indeed “masterworks” and some new material. continue to be held up by The University of California Press gets a head start music critics as bench- on the centenary by reissuing the English version of marks of Weill interpreta- Speak Low in a paperback edition this month. Critics tion. from around the world praised the 1996 hardcover edi- tion as an outstanding achievement. Events Overlook Press will publish Lenya the Legend: A Pic- The New York-based torial Autobiography in the summer of 1998, an illustrat- American Foundation for ed narrative of Lenya’s life, told in her own words, AIDS Research (AmFAR) assembled entirely from interviews, correspondence, will be the beneficiary of autobiographical notes, and other writings. Compiled an all-star Broadway gala and edited by David Farneth, director of the Weill-Lenya tribute to Lenya on 18 Research Center, the book features nearly 350 photos October 1998 at the Majes- (300 black-and-white and 50 color) showing Lenya’s tic Theatre. -

Weill, Kurt (Julian)

Weill, Kurt (Julian) (b Dessau, 2 March 1900; d New York, 3 April 1950). German composer, American citizen from 1943. He was one of the outstanding composers in the generation that came to maturity after World War I, and a key figure in the development of modern forms of musical theatre. His successful and innovatory work for Broadway during the 1940s was a development in more popular terms of the exploratory stage works that had made him the foremost avant- garde theatre composer of the Weimar Republic. 1. Life. Weill‟s father Albert was chief cantor at the synagogue in Dessau from 1899 to 1919 and was himself a composer, mostly of liturgical music and sacred motets. Kurt was the third of his four children, all of whom were from an early age taught music and taken regularly to the opera. Despite its strong Wagnerian emphasis, the Hoftheater‟s repertory was broad enough to provide the young Weill with a wide range of music-theatrical experiences which were supplemented by the orchestra‟s subscription concerts and by much domestic music-making. Weill began to show an interest in composition as he entered his teens. By 1915 the evidence of a creative bent was such that his father sought the advice of Albert Bing, the assistant conductor at the Hoftheater. Bing was so impressed by Weill‟s gifts that he undertook to teach him himself. For three years Bing and his wife, a sister of the Expressionist playwright Carl Sternheim, provided Weill with what almost amounted to a second home and introduced him a world of metropolitan sophistication. -

559288 Bk Wuorinen US

AMERICAN CLASSICS SONGS OF PEACE AND PRAISE Choral Music from Queens College Weisgall • Brings • Mandelbaum • Smaldone Sheng • Schober • Saylor • Kraft The New York Virtuoso Singers Harold Rosenbaum Queens College Choir and Vocal Ensemble Bright Sheng • James John SONGS OF PEACE AND PRAISE Songs of Peace and Praise Choral Music from Queens College Choral Music from Queens College Hugo Weisgall (1912–1997) Bruce Saylor (b. 1946) The choral music on this recording represents a group of Foundation. He twice served as composer-in-residence at composers who are or were at one time faculty members of the American Academy in Rome, was president of the 1 God is due praise (Ki lo noeh) (1958) 2:34 Missa Constantiae (2007) the Aaron Copland School of Music at Queens College, American Music Center for ten years, and also served as 8 Kyrie 1:31 CUNY. It was conceived as a vehicle to celebrate the long president of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Allen Brings (b. 1934) 9 Sanctus 1:03 history of composers associated with the school, through Letters. Weisgall is a former director of the composer-in- 2 In paradisum (1957) 3:15 0 Benedictus 1:30 the vocal excellence of the incomparable New York residence program for the Lyric Opera of Chicago and was ! Agnus Dei 3:06 Virtuoso Singers, and the vibrant talents of the students in professor of music at Queens College from 1961 to 1983. Joel Mandelbaum (b. 1932) the Queens College Choir and Vocal Ensemble. A Weisgall’s God is due praise (Ki lo noeh) is a musical 3 The Village – Act 1, Finale (1995) 4:53 somewhat larger selection of works was performed in April setting of one of the hymns traditionally sung by Leo Kraft (1922–2014) 2015 at Merkin Hall in NYC, and all were recorded in the Ashkenazi Jews at the conclusion of the Passover Seder. -

Chicago Jewish History

Look to the rock from which you were hewn Vol. 28, No. 3, Summer 2004 chicago jewish historical society chicago jewish history IN THIS ISSUE Ed Mazur to Speak on “Politics, 1654-2004: Celebrate Jews, and Elections, 1850-2004” 350 Years of Jewish Save the Date: Sunday, Oct. 31 Life in America! What’s Doing at Edward H. Mazur, Ph.D., nationally recognized authority on Other Jewish Historical politics and the Jewish voter, will be Societies in the USA the featured speaker at the next Isaac Van Grove— open meeting of the Chicago Jewish Chanukah, Romance, Historical Society on Sunday, and The Eternal October 31, at Temple Sholom, 3480 North Lake Shore Drive. [Rail] Road The program will begin at 2:30 From the Archives: p.m., following a social hour with (Left) Jacob Arvey and Abraham Skokie’s Cong. Bnai refreshments at 1:30, a brief review Lincoln Marovitz, important Jewish Emunah, 1953-2004 of the year’s activities by CJHS figures in Chicago politics. President Walter Roth, and the Undated. Chicago Jewish Archives. Report on June 27 election of Board members. Meeting: “History of Author of Minyans for a Prairie Chicagoan, born and raised in Cong. BJBE/Jewish City: The Politics of Chicago Jewry, Humboldt Park, who has resided in Issues and Chicago 1850-1940, and contributor to Rogers Park, Hyde Park, New Town Ethnic Chicago and The Dictionary and the Gold Coast. He is a tour Jews in the Civil War” of American Mayors, Edward Mazur guide for the Mayor’s Office of Author! Author! CJHS has written more than fifty articles Cultural Affairs. -

Liberal Or Zionist? Ambiguity Or Ambivalence? Reply to Jonathan Hogg

Eras Journal - Dubnov, A.: Liberal or Zionist? Ambiguity or Ambivalence? Reply to Jonathan Hogg Liberal or Zionist? Ambiguity or Ambivalence? Reply to Jonathan Hogg Arie Dubnov (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) Whether defined as an ideology, a dogma or a creed, or more loosely, as a set of neutral values and principles with no clear hierarchy, most interpreters would describe Liberalism as a predominantly British world-view. For that reason it is not surprising that the political thought of Sir Isaiah Berlin (1909-1997), one of the most prominent defenders of Liberalism in the twentieth century, is also interpreted in most cases through the prism of this English, or Anglo-American intellectual tradition, although he himself defined his Englishness only as one of the three strands of his life.[1] Ignoring Berlin's Russian-Jewish identity, or treating it merely as a biographical fact makes it hard for historians to reinterpret and contextualize Berlin's thought. The main merit in Jonathan Hogg's thought-provoking essay is that it insists on taking seriously two critical questions, which might help in changing this perspective.[2]First, it inquires into the nature of Isaiah Berlin's role within Cold War liberal discourse, and secondly, it seeks to comprehend the exact nature of his Zionism. By doing so Hogg offers Berlin's future interpreters two major themes upon which to focus. Moreover, he prepares the ground for a more inclusive, coherent and comprehensive study of Berlin's thought, one that would treat it as a multilayered whole. Here, however, I will try to show that although Hogg posits two essential questions, the answers he proffers are not always sufficient or convincing.