Iggy Azalea and the Reality Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARIA TOP 50 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2011 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 50 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2011 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 MAKING MIRRORS Gotye <P>2 ELEV/UMA ELEVENCD101 2 REECE MASTIN Reece Mastin <P> SME 88691916002 3 THE BEST OF COLD CHISEL - ALL FOR YOU Cold Chisel <P> WAR 5249889762 4 ROY Damien Leith <P> SME 88697892492 5 MOONFIRE Boy & Bear <P> ISL/UMA 2777355 6 RRAKALA Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu <G> SFM/MGM SFGU110402 7 DOWN THE WAY Angus & Julia Stone <P>3 CAP/EMI 6263842 8 SEEKER LOVER KEEPER Seeker Lover Keeper <G> DEW/UMA DEW9000330 9 THE LIFE OF RILEY Drapht <G> AYEM/SME AYEMS001 10 BIRDS OF TOKYO Birds Of Tokyo <P> CAP/EMI 6473012 11 WHITE HEAT: 30 HITS Icehouse <G> DIVA/UMA DIVAU1015C 12 BLUE SKY BLUE Pete Murray <G> SME 88697856202 13 TWENTY TEN Guy Sebastian <P> SME 88697800722 14 FALLING & FLYING 360 SMR/EMI SOLM8005 15 PRISONER The Jezabels <G> IDP/MGM JEZ004 16 YES I AM Jack Vidgen <G> SME 88697968532 17 ULTIMATE HITS Lee Kernaghan ABC/UMA 8800919 18 ALTIYAN CHILDS Altiyan Childs <P> SME 88697818642 19 RUNNING ON AIR Bliss N Eso <P> ILL/UMA ILL034CD 20 THE VERY VERY BEST OF CROWDED HOUSE Crowded House <G> CAP/EMI 9174032 21 GILGAMESH Gypsy & The Cat <G> SME 88697806792 22 SONGS FROM THE HEART Mark Vincent SME 88697927992 23 FOOTPRINTS - THE BEST OF POWDERFINGER 2001-2011 Powderfinger <G> UMA 2777141 24 THE ACOUSTIC CHAPEL SESSIONS John Farnham SME 88697969872 25 FINGERPRINTS & FOOTPRINTS Powderfinger UMA 2787366 26 GET 'EM GIRLS Jessica Mauboy <G> SME 88697784472 27 GHOSTS OF THE PAST Eskimo Joe WAR 5249871942 28 TO THE HORSES Lanie Lane IVY/UMA IVY121 29 GET CLOSER Keith Urban <G> CAP/EMI 9474212 30 LET'S GO David Campbell SME 88697987582 31 THE ENDING IS JUST THE BEGINNING REPEATING The Living End <G> DEW/UMA DEW9000353 32 THE EXPERIMENT Art vs. -

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson PACKET ONE 1. This character’s coach says that although it “takes all kinds to build a freeway” he is not equipped for this character’s kind of weirdness close the playoffs. This character lost his virginity to the homecoming queen and the prom queen at the same time and says he’ll be(*) “scoring more than baskets” at an away game and ends up in a teacher’s room wearing a thong which inspires the entire basketball team to start wearing them at practice. When Carrie brags about dating this character, Heather, played by Ashanti, hits her in the back of the head with a volleyball before Brittany Snow’s character breaks up the fight. Four girls team up to get back at this high school basketball star for dating all of them at once. For 10 points, name this character who “must die.” ANSWER: John Tucker [accept either] 2. The hosts of this series that premiered in 2003 once crafted a combat robot named Blendo, and one of those men served as a guest judge on the 2016 season of BattleBots. After accidentally shooting a penny into a fluorescent light on one episode of this show, its cast had to be evacuated due to mercury vapor. On a “Viewers’ Special” episode of this show, its hosts(*) attempted to sneeze with their eyes open, before firing cigarette butts from a rifle. This show’s hosts produced the short-lived series Unchained Reaction, which also aired on the Discovery Channel. -

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

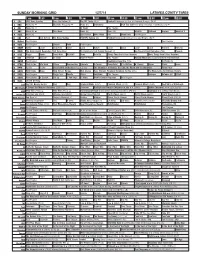

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Chart: Top25 VIDEO HIP HOP

Chart: Top25_VIDEO_HIP HOP Report Date (TW): 2012-04-29 --- Previous Report Date(LW): 2012-04-22 TW LW TITLE ARTIST GENRE RECORD LABEL 1 3 Beez In The Trap (explicit) Ft. 2 Chainz Nicki Minaj Hip Hop Cash Money Records 2 2 Leave You Alone (explicit) Ft. Ne-yo Young Jeezy Hip Hop Island Records 3 6 Faded Tyga Ft. Lil Wayne Hip Hop YMCMB 4 4 Take Care Ft. Rihanna Drake Hip Hop Cash Money Records 5 10 Bitch Betta Have My Money Tyga Ft Yg Kurupt Hip Hop YMCMB 6 13 So Good B.o.b Hip Hop Atlantic Records 7 21 Lap Dance Tyga Hip Hop YMCMB 8 14 Nobodys Perfect (explicit) Ft. Missy Elliott J. Cole Hip Hop RCA Records 9 16 Fuck Da City Up Ft. Young Jeezy (ditry) T.i. Hip Hop Grand Hustle Records / Atlantic 10 19 Fast Lane E-40 Hip Hop SickWit it Records / Warner Bros 11 15 Im In Love With A White Girl Ft. Yo Gotti Gucci Mane Hip Hop Warner Bros 12 20 Hot Wheels (dirty) T.i. Travis Porter And Young Dro Hip Hop Grand Hustle Records 13 Hyfr Ft. Lil Wayne Drake Hip Hop Cash Money Records 14 1 Ayy Ladies Travis Porter Ft. Tyga Hip Hop RCA Records 15 17 88 Ft. Jadakiss Diggy Hip Hop Warner Bros Records 16 18 Sabotage Ft. Lloyd Wale Hip Hop MayBach Music 17 22 Boobie Miles (explicit) Big K.r.i.t. Hip Hop Def Jam Records 18 23 What Yo Name Iz (remix) Kirko Bangz Ft. Big Sean, Wale And Bun B Hip Hop Warner Bros. -

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

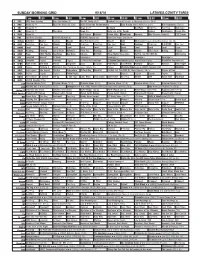

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

Fundraising, Direct & Crm Engagement

AUSTRALIAN FIRST! TOUCH MTV’S BALLS AT BIG DAY OUT 2014 CATCH ALL THE LOCALLY PRODUCED ACTION FROM THE TOUR ON-AIR AND ONLINE www.mtv.com.au/bigdayout #mtvbdo FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: In an exciting Australian first, MTV and The Creative Shop will be giving fans at this year’s Big Day Out tour the opportunity to get touchy feely with “MTV’s Balls”. The oversized beach balls will contain a series of camera’s and aerials, capturing and streaming content from the event and giving attendees a chance to relive their experience online and for fans that miss out, a chance to watch the artists live from a punters point of view directly in the crowd. A gallery of images will be available the following day on MTV’s Facebook page www.facebook.com/mtvaustralia. “MTV was recently confirmed as one of the leading social media brands in the world, and has 1.6 million connections in Australia and New Zealand. We wanted to create a new, unique way to engage with that huge audience and generate innovative fun content that’s sharable, and that we will also feature MTV,” said Simon Bates, Director of MTV Australia and New Zealand. The aptly named Social Balls are a main feature across the full 2014 Big Day Out tour having been showcased at the Auckland and Gold Coast events already, with Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide and Perth still to come. Bands involved include The Lumineers, Bluejuice, The Hives, Bliss N Eso, Mac Miller, Primus, Tame Impala and Grouplove. “It’s great to see brands move and adapt to the rapidly changing landscape of the music festival space, whilst all the time focusing on meeting the needs of the ever-connected consumer. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

Holiday Gift Guide 2007 Week One of Two Special Pullout Section P

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 November 28, 2007 • vol 23 No 11 windy city times’ holiday gift guide 2007 week one of two special pullout section p. 13-24 World AIDS page 4 DAY Events Amy and Peter Hit Toronto page 32 Carol Ronen: Past, Present and Future BY ANDREW Davis When State Sen. Carol Ronen, D-7th Dist., steps down from the Illinois General Assembly early next year, the transition will mark the end of an era. For a decade and a half, Ronen took part in the passages of numerous measures that benefit the healthcare and LGBT communities, including the landmark gay-rights bill that Gov. Military Man Rod Blagojevich signed into law in 2005. She Lou Tharp page 34 recently talked with Windy City Times about her life—including her entry into politics and her next career move. Windy City Times: You [said in an earlier conversation with the newspaper] that your The Bible goal was not to be in political office. What was your goal? pick it up Carol Ronen: I don’t know that I had a specific Tells Them So take it home Chicagoan Michael Leppen hosted a grand premiere goal; I just never thought I’d run for political of- for the new documentary For the Bible Tells Me fice. [Running for office] wasn’t something that So, a film which Leppen helped produce. The film’s I thought was a possibility, so I was always in- #920, NOVEMBER 28, 2007 director, Daniel Karslake (pictured below with terested in working on issues and [doing] public Leppen), was on hand, as were representatives service. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands