The Link Between Molecular Cloud Structure and Turbulence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:2012.09981V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 17 Dec 2020 2 O](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3257/arxiv-2012-09981v1-astro-ph-sr-17-dec-2020-2-o-73257.webp)

Arxiv:2012.09981V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 17 Dec 2020 2 O

Contrib. Astron. Obs. Skalnat´ePleso XX, 1 { 20, (2020) DOI: to be assigned later Flare stars in nearby Galactic open clusters based on TESS data Olga Maryeva1;2, Kamil Bicz3, Caiyun Xia4, Martina Baratella5, Patrik Cechvalaˇ 6 and Krisztian Vida7 1 Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences 251 65 Ondˇrejov,The Czech Republic(E-mail: [email protected]) 2 Lomonosov Moscow State University, Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Universitetsky pr. 13, 119234, Moscow, Russia 3 Astronomical Institute, University of Wroc law, Kopernika 11, 51-622 Wroc law, Poland 4 Department of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Kotl´aˇrsk´a2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic 5 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia Galileo Galilei, Vicolo Osservatorio 3, 35122, Padova, Italy, (E-mail: [email protected]) 6 Department of Astronomy, Physics of the Earth and Meteorology, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Informatics, Comenius University in Bratislava, Mlynsk´adolina F-2, 842 48 Bratislava, Slovakia 7 Konkoly Observatory, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, H-1121 Budapest, Konkoly Thege Mikl´os´ut15-17, Hungary Received: September ??, 2020; Accepted: ????????? ??, 2020 Abstract. The study is devoted to search for flare stars among confirmed members of Galactic open clusters using high-cadence photometry from TESS mission. We analyzed 957 high-cadence light curves of members from 136 open clusters. As a result, 56 flare stars were found, among them 8 hot B-A type ob- jects. Of all flares, 63 % were detected in sample of cool stars (Teff < 5000 K), and 29 % { in stars of spectral type G, while 23 % in K-type stars and ap- proximately 34% of all detected flares are in M-type stars. -

Curriculum Vitae - 24 March 2020

Dr. Eric E. Mamajek Curriculum Vitae - 24 March 2020 Jet Propulsion Laboratory Phone: (818) 354-2153 4800 Oak Grove Drive FAX: (818) 393-4950 MS 321-162 [email protected] Pasadena, CA 91109-8099 https://science.jpl.nasa.gov/people/Mamajek/ Positions 2020- Discipline Program Manager - Exoplanets, Astro. & Physics Directorate, JPL/Caltech 2016- Deputy Program Chief Scientist, NASA Exoplanet Exploration Program, JPL/Caltech 2017- Professor of Physics & Astronomy (Research), University of Rochester 2016-2017 Visiting Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester 2016 Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester 2013-2016 Associate Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester 2011-2012 Associate Astronomer, NOAO, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory 2008-2013 Assistant Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester (on leave 2011-2012) 2004-2008 Clay Postdoctoral Fellow, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics 2000-2004 Graduate Research Assistant, University of Arizona, Astronomy 1999-2000 Graduate Teaching Assistant, University of Arizona, Astronomy 1998-1999 J. William Fulbright Fellow, Australia, ADFA/UNSW School of Physics Languages English (native), Spanish (advanced) Education 2004 Ph.D. The University of Arizona, Astronomy 2001 M.S. The University of Arizona, Astronomy 2000 M.Sc. The University of New South Wales, ADFA, Physics 1998 B.S. The Pennsylvania State University, Astronomy & Astrophysics, Physics 1993 H.S. Bethel Park High School Research Interests Formation and Evolution -

Cygnus OB2 – a Young Globular Cluster in the Milky Way Jürgen Knödlseder

Cygnus OB2 – a young globular cluster in the Milky Way Jürgen Knödlseder To cite this version: Jürgen Knödlseder. Cygnus OB2 – a young globular cluster in the Milky Way. Astronomy and Astrophysics - A&A, EDP Sciences, 2000, 360, pp.539 - 548. hal-01381935 HAL Id: hal-01381935 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01381935 Submitted on 14 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Astron. Astrophys. 360, 539–548 (2000) ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS Cygnus OB2–ayoung globular cluster in the Milky Way J. Knodlseder¨ INTEGRAL Science Data Centre, Chemin d’Ecogia 16, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland Centre d’Etude Spatiale des Rayonnements, CNRS/UPS, B.P. 4346, 31028 Toulouse Cedex 4, France ([email protected]) Received 31 May 2000 / Accepted 23 June 2000 Abstract. The morphology and stellar content of the Cygnus particularly good region to address such questions, since it is OB2 association has been determined using 2MASS infrared extremely rich (e.g. Reddish et al. 1966, hereafter RLP), and observations in the J, H, and K bands. The analysis reveals contains some of the most luminous stars known in our Galaxy a spherically symmetric association of ∼ 2◦ in diameter with (e.g. -

POSTERS SESSION I: Atmospheres of Massive Stars

Abstracts of Posters 25 POSTERS (Grouped by sessions in alphabetical order by first author) SESSION I: Atmospheres of Massive Stars I-1. Pulsational Seeding of Structure in a Line-Driven Stellar Wind Nurdan Anilmis & Stan Owocki, University of Delaware Massive stars often exhibit signatures of radial or non-radial pulsation, and in principal these can play a key role in seeding structure in their radiatively driven stellar wind. We have been carrying out time-dependent hydrodynamical simulations of such winds with time-variable surface brightness and lower boundary condi- tions that are intended to mimic the forms expected from stellar pulsation. We present sample results for a strong radial pulsation, using also an SEI (Sobolev with Exact Integration) line-transfer code to derive characteristic line-profile signatures of the resulting wind structure. Future work will compare these with observed signatures in a variety of specific stars known to be radial and non-radial pulsators. I-2. Wind and Photospheric Variability in Late-B Supergiants Matt Austin, University College London (UCL); Nevyana Markova, National Astronomical Observatory, Bulgaria; Raman Prinja, UCL There is currently a growing realisation that the time-variable properties of massive stars can have a funda- mental influence in the determination of key parameters. Specifically, the fact that the winds may be highly clumped and structured can lead to significant downward revision in the mass-loss rates of OB stars. While wind clumping is generally well studied in O-type stars, it is by contrast poorly understood in B stars. In this study we present the analysis of optical data of the B8 Iae star HD 199478. -

Impact of Supernovae on Molecular Cloud Evolution Dynamics and Structure

Impact of Supernovae on Molecular Cloud Evolution Dynamics and Structure Bastian K¨ortgen1, Daniel Seifried1, and Robi Banerjee1 1Hamburger Sternwarte, Gojenbergsweg 112, 21029 Hamburg, Germany [email protected] Introduction We perform numerical simulations of colliding streams of the WNM, including magnetic fields and self{gravity, to analyse the formation and evolution of molecular clouds subject to supernova feedback from massive stars. Simulation Setup The Supernova Subgrid Model The equations of MHD together with selfgravity and heating and cooling are evolved in time using the The supernova feedback is included into the model by means of a Sedov blast FLASH code [Fryxell et al., 2000]. We use a constant heating rate Γ and the cooling function Λ according to wave solution. We define a volume of radius R = 1 pc centered on the sink [Koyama and Inutsuka, 2000] and [V´azquez-Semadeni et al., 2007]. The table below lists the initial conditions. particle. Within this volume each grid cell is assigned a certain radial veloc- ity vc. This velocity depends on the kinetic energy input. Additionally we U Sink Particle Parameter Value Parameter Value inject thermal energy, which then gives the total amount of injected energy of E = 1051 erg with 65 % thermal and 35 % kinetic energy according to the Flow Mach number Mf 2.0 Alfv´en velocity va [km/s] 5.8 sn Sedov solution. The cell velocity is Turbulent Mach number Ms 0.5 Alfv´enic Mach number Ma 1.96 r vc = Ush Temperature [K] 5000 Plasma Beta β = Pth=PB 1.93 R Number density n cm−3 1.0 Flow Length [pc] 112 Figure 1: Schematic of the where U is the shock velocity, depending on the kinetic energy input. -

Binocular Challenge Here

AHSP Binocular Observing Award Compiled by Phil Harrington www.philharrington.net • To qualify for the BOA pin, you must see 15 of the following 20 binocular targets. Check off each as you spot them. Seen # Object Const. Type* RA Dec Mag Size Nickname 1. M13 Her GC 16 41.7 +36 28 5.9 16' Great Hercules Globular 2. M57 Lyr PN 18 53.6 +33 02 9.7 86"x62" Ring Nebula 3. Collinder 399 Vul AS 19 25.4 +20 11 3.6 60' Coathanger/Brocchi’s Cluster 3.1 4. Albireo Cyg Dbl 19 30.7 +27 57 35” Color Contrasting Double 5.1 5. M27 Vul PN 19 59.6 +22 43 8.1 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 6. NGC 6992 Cyg SNR 20 56.4 +31 43 - 60'x8 Veil Nebula (east) 7. NGC 7000 Cyg BN 20 58.8 +44 20 - 120'x100' North America Nebula 8. M15 Peg GC 21 30.0 +12 10 7.5 12’ Great Pegasus Cluster 9. M39 Cyg OC 21 32.2 +48 26 4.6 32' 10. Barnard 168 Cyg DN 21 53.2 +47 12 - 100'x10' West of Cocoon Nebula 11. IC 5146 Cyg BN/OC 21 53.5 +47 16 - 12'x12' Cocoon Nebula 12. M110 And Gx 00 40.4 +41 41 10 17’x10’ 13. M32 And Gx 00 42.8 +40 52 10 8’x6’ 14. M31 And Gx 00 42.8 +41 16 4.5 178’ Andromeda Galaxy 15. NGC 457 Cas OC 01 19.1 +58 20 6.4 13’ Owl Cluster/ET Cluster 16. -

The E-MERLIN 21 Cm Legacy Survey of Cygnus OB2

This is a repository copy of COBRaS: The e-MERLIN 21 cm Legacy survey of Cygnus OB2. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/162252/ Version: Published Version Article: Morford, JC, Fenech, DM, Prinja, RK et al. (12 more authors) (2020) COBRaS: The e-MERLIN 21 cm Legacy survey of Cygnus OB2. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 637. A64. ISSN 0004-6361 https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201731379 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ A&A 637, A64 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201731379 Astronomy c ESO 2020 & Astrophysics COBRaS: The e-MERLIN 21 cm Legacy survey of Cygnus OB2 J. C. Morford1, D. M. Fenech1,2, R. K. Prinja1, R. Blomme3, J. A. Yates1, J. J. Drake4, S. P. S. Eyres5,6, A. M. S. Richards7, I. R. Stevens8, N. J. Wright9, J. S. Clark10, S. -

Useful Constants

Appendix A Useful Constants A.1 Physical Constants Table A.1 Physical constants in SI units Symbol Constant Value c Speed of light 2.997925 × 108 m/s −19 e Elementary charge 1.602191 × 10 C −12 2 2 3 ε0 Permittivity 8.854 × 10 C s / kgm −7 2 μ0 Permeability 4π × 10 kgm/C −27 mH Atomic mass unit 1.660531 × 10 kg −31 me Electron mass 9.109558 × 10 kg −27 mp Proton mass 1.672614 × 10 kg −27 mn Neutron mass 1.674920 × 10 kg h Planck constant 6.626196 × 10−34 Js h¯ Planck constant 1.054591 × 10−34 Js R Gas constant 8.314510 × 103 J/(kgK) −23 k Boltzmann constant 1.380622 × 10 J/K −8 2 4 σ Stefan–Boltzmann constant 5.66961 × 10 W/ m K G Gravitational constant 6.6732 × 10−11 m3/ kgs2 M. Benacquista, An Introduction to the Evolution of Single and Binary Stars, 223 Undergraduate Lecture Notes in Physics, DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-9991-7, © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 224 A Useful Constants Table A.2 Useful combinations and alternate units Symbol Constant Value 2 mHc Atomic mass unit 931.50MeV 2 mec Electron rest mass energy 511.00keV 2 mpc Proton rest mass energy 938.28MeV 2 mnc Neutron rest mass energy 939.57MeV h Planck constant 4.136 × 10−15 eVs h¯ Planck constant 6.582 × 10−16 eVs k Boltzmann constant 8.617 × 10−5 eV/K hc 1,240eVnm hc¯ 197.3eVnm 2 e /(4πε0) 1.440eVnm A.2 Astronomical Constants Table A.3 Astronomical units Symbol Constant Value AU Astronomical unit 1.4959787066 × 1011 m ly Light year 9.460730472 × 1015 m pc Parsec 2.0624806 × 105 AU 3.2615638ly 3.0856776 × 1016 m d Sidereal day 23h 56m 04.0905309s 8.61640905309 -

Ghost Supernova Remnants: Evidence for Pulsar Reactivation in Dusty Molecular Clouds?

Notas de Rsica NOTAS DE FÍSICA é uma pré-publicaçáo de trabalhos em Física do CBPF NOTAS DE FÍSICA is a series of preprints from CBPF Pedidos de cópias desta publicaçáfo devem ser enviados aos autores ou à: Requests for free copies of these reports should be addressed to: Divisão de Publicações do CBPF-CNPq Av. Wenceslau Braz, 71 • Fundos 22.290 - Rk> de Janeiro - RJ. Brasil CBPF-NF-034/83 GHOST SUPERNOVA RE WANTS: EVIDENCE FOR PULSAR REACTIVATION IN DUSTY MOLECULAR CLOUDS? by H.Heintzmann1 and M.Novello Centro Brasileiro de Pesquisas Físicas - CBPF/CNPq Rua Xavier Sigaud, 150 22290 - R1o de Janeiro, RJ - Brasil Mnstitut fOr Theoretische Physik der UniversUlt zu K0Tn, 5000 K01n 41, FRG Alemanha GHOST SUPERNOVA REMNANTS: EVIDENCE FOR PULSAR REACTIVATION IN DUSTY MOLECULAR CLOUDS? There is ample albeit ambiguous evidence in favour of a new model for pulsar evolution, according to which pulsars aay only function as regularly pulsed emitters if an accretion disc provides a sufficiently continuous return-current to the radio pulsar (neutron star). On its way through the galaxy the pulsar will consume the disc within some My and travel further (away from the galactic plane) some 100 My without functioning as a pulsar. Back to the galactic plane it may collide with a dense molecular cloud and turn-on for some ten thousand years as a RSntgen source through accretion. The response of the dusty cloud to the collision with the pulsar should resemble a super- nova remnant ("ghost supernova remnant") whereas the pulsar will have been endowed with a new disc, new angular momentum and a new magnetic field . -

Diffuse X-Ray Emission in the Cygnus OB2 Association

to appear in special issue ApJSS., 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style AASTeX6 v. 1.0 DIFFUSE X-RAY EMISSION IN THE CYGNUS OB2 ASSOCIATION. J. F. Albacete Colombo1, J. J. Drake2,E.Flaccomio3,N.J.Wright4, V. Kashyap2,M.G.Guarcello3,K.Briggs5,J.E.Drew6, D. M. Fenech7,G.Micela3, M. McCollough2,R.K.Prinja7,N.Schneider8,S.Sciortino3,J.S.Vink9 1Universidad de R´ıo Negro, Sede Atl´antica, Viedma CP8500, Argentina. 2Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA 02138, U.S.A 3INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo, Piazza del Parlamento 1, 90134 Palermo, Italy. 4Astrophysics Group, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire ST5 5BG, UK. 5Hamburger Sternwarte, University of Hamburg, Gojenbergsweg 112, 21029, Hamburg, Germany. 6School of Physics, Astronomy & Mathematics, University of Hertfordshire, College Lane, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, AL10 9AB, UK. 7Department of Physics and Astronomy, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK. 8I. Physik. Institut, University of Cologne, D-50937 Cologne, Germany. 9Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, College Hill, Armagh BT61 9DG, Northern Ireland, UK. ABSTRACT We present a large-scale study of diffuse X-ray emission in the nearby massive stellar association Cygnus OB2 as part of the Chandra Cygnus OB2 Legacy Program. We used 40 Chandra X-ray ACIS-I observations covering ∼1.0 deg2. After removing 7924 point-like sources detected in our survey, background-corrected X-ray emission, the adaptive smoothing reveals large-scale diffuse X-ray emission. Diffuse emission was de- tected in the sub-bands Soft [0.5:1.2] and Medium [1.2:2.5], and marginally in the Hard [2.5:7.0] keV band. -

Instruction Manual Meade Instruments Corporation

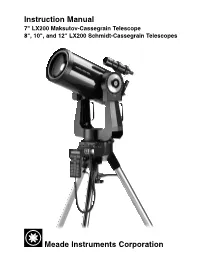

Instruction Manual 7" LX200 Maksutov-Cassegrain Telescope 8", 10", and 12" LX200 Schmidt-Cassegrain Telescopes Meade Instruments Corporation NOTE: Instructions for the use of optional accessories are not included in this manual. For details in this regard, see the Meade General Catalog. (2) (1) (1) (2) Ray (2) 1/2° Ray (1) 8.218" (2) 8.016" (1) 8.0" Secondary 8.0" Mirror Focal Plane Secondary Primary Baffle Tube Baffle Field Stops Correcting Primary Mirror Plate The Meade Schmidt-Cassegrain Optical System (Diagram not to scale) In the Schmidt-Cassegrain design of the Meade 8", 10", and 12" models, light enters from the right, passes through a thin lens with 2-sided aspheric correction (“correcting plate”), proceeds to a spherical primary mirror, and then to a convex aspheric secondary mirror. The convex secondary mirror multiplies the effective focal length of the primary mirror and results in a focus at the focal plane, with light passing through a central perforation in the primary mirror. The 8", 10", and 12" models include oversize 8.25", 10.375" and 12.375" primary mirrors, respectively, yielding fully illuminated fields- of-view significantly wider than is possible with standard-size primary mirrors. Note that light ray (2) in the figure would be lost entirely, except for the oversize primary. It is this phenomenon which results in Meade 8", 10", and 12" Schmidt-Cassegrains having off-axis field illuminations 10% greater, aperture-for-aperture, than other Schmidt-Cassegrains utilizing standard-size primary mirrors. The optical design of the 4" Model 2045D is almost identical but does not include an oversize primary, since the effect in this case is small. -

Spectroscopy of 13 High Mass Stars in the Cyg OB2 Association

will be published in Astronomy Reports, 2013, vol. 67, No. 7 Spectroscopy of 13 high mass stars in the Cyg OB2 association E.L. Chentsov, V.G. Klochkova, V.E. Panchuk, M.V. Yushkin Special Astrophysical Observatory RAS, Nizhnij Arkhyz, Russia March 15, 2018 Abstract Aiming to explore weak spectral features of stellar and interstellar origin we used the NES echelle spectrograph of the 6–m telescope to obtain high–resolution spectra for 13 hot O3–B4 stars in the Cyg OB2 association, including a high luminous star No. 12. Velocity fields in the atmospheres and interstellar medium, characteristics of optical spectra and line profiles are investigated. The cascade star formation scheme for the association is confirmed. Evidence is presented suggesting that the hypergiant Cyg OB2 No. 12 is an LBV object and that its anomalous reddening has a circumstellar nature. 1. Introduction Among hypergiants of the Galaxy, those belonging to stellar associations are most attractive for study. Membership in a stellar group makes it easier to estimate a stars age, luminosity, and center of mass radial velocity, which is needed to introduce a zero point for the system of velocities observed in the stellar atmosphere and wind. In addition, studies of stars with extreme luminosities and mass loss rates can naturally be expanded to their influence on the associations gas and dust component and the star formation process. In the present paper, we address this two-sided problem for the enigmatic star No. 12 and other members h m of the Cyg OB2 association. This association (initially named VI Cyg; α2000 = 20 33.2 , o o o δ2000 = +41.32 , l = 80.2 , b = +0.8 ) was discovered in the middle of the 20-th century and still remains one of the most actively studied objects in our Galaxy.