Canterbury Christ Church University's Repository of Research Outputs Http

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Lythans Park Brochure

St Lythans Park Two, three, four and five bedroom homes in Culverhouse Cross, Cardiff A reputation you can rely on When it comes to buying your new home it is reassuring to Today Bellway is one of Britain’s largest house building know that you are dealing with one of the most successful companies and is continuing to grow throughout the companies in the country, with a reputation built on country. Since its formation, Bellway has built and sold over designing and creating fine houses and apartments 100,000 homes catering for first time buyers to more nationwide backed up with one of the industry’s best seasoned home buyers and their families. The Group’s after-care services. rapid growth has turned Bellway into a multi-million pound company, employing over 2,000 people directly and many In 1946 John and Russell Bell, newly demobbed, more sub-contractors. From its original base in Newcastle joined their father John T. Bell in a small family owned upon Tyne the Group has expanded in to all regions of the housebuilding business in Newcastle upon Tyne. From the country and is now poised for further growth. very beginning John T. Bell & Sons, as the new company was called, were determined to break the mould. In the Our homes are designed, built and marketed by local early 1950s Kenneth Bell joined his brothers in the teams operating from regional offices managed and company and new approaches to design layout and staffed by local people. This allows the company to stay finishes were developed. -

Handbook to Cardiff and the Neighborhood (With Map)

HANDBOOK British Asscciation CARUTFF1920. BRITISH ASSOCIATION CARDIFF MEETING, 1920. Handbook to Cardiff AND THE NEIGHBOURHOOD (WITH MAP). Prepared by various Authors for the Publication Sub-Committee, and edited by HOWARD M. HALLETT. F.E.S. CARDIFF. MCMXX. PREFACE. This Handbook has been prepared under the direction of the Publications Sub-Committee, and edited by Mr. H. M. Hallett. They desire me as Chairman to place on record their thanks to the various authors who have supplied articles. It is a matter for regret that the state of Mr. Ward's health did not permit him to prepare an account of the Roman antiquities. D. R. Paterson. Cardiff, August, 1920. — ....,.., CONTENTS. PAGE Preface Prehistoric Remains in Cardiff and Neiglibourhood (John Ward) . 1 The Lordship of Glamorgan (J. S. Corbett) . 22 Local Place-Names (H. J. Randall) . 54 Cardiff and its Municipal Government (J. L. Wheatley) . 63 The Public Buildings of Cardiff (W. S. Purchox and Harry Farr) . 73 Education in Cardiff (H. M. Thompson) . 86 The Cardiff Public Liljrary (Harry Farr) . 104 The History of iNIuseums in Cardiff I.—The Museum as a Municipal Institution (John Ward) . 112 II. —The Museum as a National Institution (A. H. Lee) 119 The Railways of the Cardiff District (Tho^. H. Walker) 125 The Docks of the District (W. J. Holloway) . 143 Shipping (R. O. Sanderson) . 155 Mining Features of the South Wales Coalfield (Hugh Brajiwell) . 160 Coal Trade of South Wales (Finlay A. Gibson) . 169 Iron and Steel (David E. Roberts) . 176 Ship Repairing (T. Allan Johnson) . 182 Pateift Fuel Industry (Guy de G. -

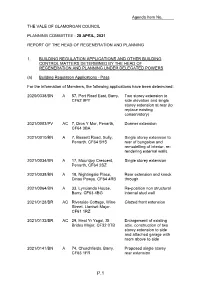

Planning Committee Report 20-04-21

Agenda Item No. THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE : 28 APRIL, 2021 REPORT OF THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING 1. BUILDING REGULATION APPLICATIONS AND OTHER BUILDING CONTROL MATTERS DETERMINED BY THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING UNDER DELEGATED POWERS (a) Building Regulation Applications - Pass For the information of Members, the following applications have been determined: 2020/0338/BN A 57, Port Road East, Barry. Two storey extension to CF62 9PY side elevation and single storey extension at rear (to replace existing conservatory) 2021/0003/PV AC 7, Dros Y Mor, Penarth, Dormer extension CF64 3BA 2021/0010/BN A 7, Bassett Road, Sully, Single storey extension to Penarth. CF64 5HS rear of bungalow and remodelling of interior, re- rendering external walls. 2021/0034/BN A 17, Mountjoy Crescent, Single storey extension Penarth, CF64 2SZ 2021/0038/BN A 18, Nightingale Place, Rear extension and knock Dinas Powys. CF64 4RB through 2021/0064/BN A 33, Lyncianda House, Re-position non structural Barry. CF63 4BG internal stud wall 2021/0128/BR AC Riverside Cottage, Wine Glazed front extension Street, Llantwit Major. CF61 1RZ 2021/0132/BR AC 29, Heol Yr Ysgol, St Enlargement of existing Brides Major, CF32 0TB attic, construction of two storey extension to side and attached garage with room above to side 2021/0141/BN A 74, Churchfields, Barry. Proposed single storey CF63 1FR rear extension P.1 2021/0145/BN A 11, Archer Road, Penarth, Loft conversion and new CF64 3HW fibre slate roof 2021/0146/BN A 30, Heath Avenue, Replace existing beam Penarth. -

Maesyfelin Chambered Tomb, St Lythans

Great Archaeological Sites in the Vale of Glamorgan 1. MAESYFELIN CHAMBERED TOMB, ST LYTHANS Although there had been Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in the Vale for millennia, the introduction of farming in the Neolithic period led to a new relationship between the land and the people who lived in it. The need to stay in one place long enough to plant seeds, look after the growing crops and bring in the harvest resulted in the creation of permanent settlements, and although very few Neolithic houses have been discovered so far in Wales do have the houses built in stone for the dead. These are known as chambered tombs. One chambered tomb stands in the valley of the River Waycock near Maesyfelin Farm outside the village of St Lythans (ST 1009 7230), from which it takes two of the names it is known by. The other is Gwal y Filiast – ‘the kennel of the greyhound bitch’, a name also given to another chambered tomb in Carmarthenshire. A large capstone perches on top of three megalithic uprights which form three sides of a short rectangle, all of the local mudstone. The other side is open. Originally this chamber stood within the eastern end of a long mound which extended westwards behind the upright that closes it off at the back, but very little now remains. There is however enough left to show that a shallow forecourt created a recess at the mound’s eastern end in front of the chamber. Although this tomb has never been properly excavated, human remains and pottery were found in 1875 in the forecourt area, presumably lying where they had been cleared out of the chamber. -

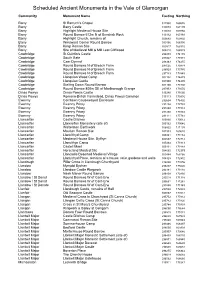

Scheduled Ancient Monuments in the Vale of Glamorgan

Scheduled Ancient Monuments in the Vale of Glamorgan Community Monument Name Easting Northing Barry St Barruch's Chapel 311930 166676 Barry Barry Castle 310078 167195 Barry Highlight Medieval House Site 310040 169750 Barry Round Barrow 612m N of Bendrick Rock 313132 167393 Barry Highlight Church, remains of 309682 169892 Barry Westward Corner Round Barrow 309166 166900 Barry Knap Roman Site 309917 166510 Barry Site of Medieval Mill & Mill Leat Cliffwood 308810 166919 Cowbridge St Quintin's Castle 298899 174170 Cowbridge South Gate 299327 174574 Cowbridge Caer Dynnaf 298363 174255 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 297025 173874 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 296929 173780 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 297133 173849 Cowbridge Llanquian Wood Camp 302152 174479 Cowbridge Llanquian Castle 301900 174405 Cowbridge Stalling Down Round Barrow 301165 174900 Cowbridge Round Barrow 800m SE of Marlborough Grange 297953 173070 Dinas Powys Dinas Powys Castle 315280 171630 Dinas Powys Romano-British Farmstead, Dinas Powys Common 315113 170936 Ewenny Corntown Causewayed Enclosure 292604 176402 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291294 177788 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291260 177814 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291200 177832 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291111 177761 Llancarfan Castle Ditches 305890 170012 Llancarfan Llancarfan Monastery (site of) 305162 170046 Llancarfan Walterston Earthwork 306822 171193 Llancarfan Moulton Roman Site 307383 169610 Llancarfan Llantrithyd Camp 303861 173184 Llancarfan Medieval House Site, Dyffryn 304537 172712 Llancarfan Llanvithyn -

Profile for Parish of Penarth and Llandough

PARISH OF PENARTH AND LLANDOUGH PARISH PROFILE St Augustine’s St Dochdwy’s Holy Nativity WELCOME Welcome to our Parish Profile. Our aim is to give you an understanding of the parish, an idea of what it might be like to be a part of our community, and what vision we have for the future of the parish. We hope it will enable you prayerfully to consider our vacancy for a new incumbent and we look forward to meeting you should you decide to apply. Church Wardens and PCC www.parishofpenarthandllandough.co.uk CONTENTS Page Page SUMMARY 2 PARISH HALL & OTHER BUILDINGS 7 PERSON SPECIFICATION 2 ADMINISTRATION 7 ABOUT PENARTH & LLANDOUGH 3 FINANCE 7 OUR PARISH PATTERN OF SERVICES 8 • Now and in the future 4 ATTENDANCE FIGURES 8 • Our churches 4 CONTACT DETAILS 8 • Spiritual tradition 5 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 9 • Music 5 PROFILE OF ALL SAINTS, PENARTH 10 • Children’s activities 5 • Lay Ministry 5 • Groups 6 • Friends of St Augustine’s 6 • Community Involvement 6 SUMMARY The Parish is located in the seaside town of Penarth and adjoining areas, five miles south-west of Cardiff. There are three well-maintained churches. The style of worship is varied but traditional, with a strong music base particularly at St Augustine’s. Main needs include developing the lay ministry and re-introducing the children’s ministry, whilst maintaining support for the faithful but largely older congregation. Links with the community and other churches also need to be strengthened. The Parish is likely to join with the adjacent parish of All Saints in the future to form a Ministry Area. -

Activaleactivale Youth Directory - Llawlyfr Gwasanaethau Ieuenctid

activaleactivale youth directory - llawlyfr gwasanaethau ieuenctid Contents - Cynnwys Introduction & Acknowledgements 2 Cyflwyniad a Chydnabyddiaeth 3 Updating Information & Contact Details 4 Diweddaru Gwybodaeth Bersonol a Manylion Cysylltu 5 Registration Form 6 Ffurflen Gofrestru 6 It’s about You! 10 Mae hyn I gyd amdanoch chi! 13 Safe Practice 16 Cadw'n Ddiogel 17 Disclaimer 18 Ymwadiad 19 Our Use of Categories 20 Categorïau yn y llyfr 21 Alphabetical Index Category Index: arts index education index employment & training index environment index family & relationships index health index housing index information & advice index law & rights index leisure index money index sport index world & travel index 1 Introduction and Acknowledgements Activale is a directory of services for young people between the ages of 11 - 25 years. The Directory has been produced by the Children & Young Person's Information Service (CYPIS) through a joint project by the Young People's Partnership (YPP) and the 14-19 Network, funded by the Welsh Assembly Government. It has been produced with the help of other organisations including: Penarth Youth Project CLIC Online Young People's Partnership (YPP) 14-19 Network Vale Learning Network Sports Development Unit (Vale of Glamorgan Council) Libraries Service (Vale of Glamorgan Council) Vale Volunteer Bureau Barry College Learning & Development Directorate (Vale of Glamorgan Council) The aim is to provide a comprehensive source of information on all services and organisations that are accessible to young people, aged 11-25 years, and living in the Vale of Glamorgan. It is appropriate for use by young people themselves, carers of young people and professionals working with young people. -

South Wales Railway. NOTICE Is Hereby Given, That Application Is

4005 South Wales Railway. sannor, Llanharry, Llanharrcn, Llanilitf, church otherwise Eglwys Llangrallo, Coychurch OTICE is hereby given, that application is higher, Coychurch lower, Pencoed, Peterston N intended to be made to Parliament in the super Montein otherwise Capel Llanbad, Llandy- ensuing session, for an Act or Acts to authorize fodwg otherwise Eglwys Glynn Ogwr, Saint the construction and maintenance of a railway or Mary Hill, Llangard, Treose, Penlline otherwise railways, with all proper approaches and con- Penlywynd, Colwinstone, Ewenny, Saint Brides veniences, and with such piers, basins, break- major, Saint Brides Lampha, Soutfcerndown, waters, landing plaeeBj and other works, as may Coyty, Coyty higher, Coyty lower, Saint Brides be necessary in connection therewith, commencing minor otherwise Llansaintfred, Ynisawdre, Llan- by a junction with the Cheltenham and Great gonoyd otherwise Llangynwd, Llangonoyd higher, "Western Union Railway, at or near the point Llangonoyd lower otherwise Boyder, Llangonoyd where the said railway crosses the turnpike road Middle, Cwmdu, Lalestone, Lalestone higher, from Gloucester to Stroud, at Standish, in the Lalestone lower, Trenewydd otherwise Newcastle, county of Gloucester, and terminating on the Newcastle higher, Newcastle lower, Oldcastle, north-western shore of the bay or harbour of Fish- Bridgend, Merthyr Mawr,. Tythegston, Tythegston guard, and near to a point there known by the higher, Tythegston lower, Newton Nottage, Pyle, name of Goodwic-pier, in the county of Pem- Sker, Kenfig otherwise Mawdland, Margam, broke; which said intended railway or railways, Hafod-y-poth, Brombill, Trissant, Kenfig, Abe- and other works connected therewith, will pass rafon, Michaelstone super Afon, Michaelstone from, in, through, or into, or be situate within the super Afon higher, Michaelstone super Afoii several parishes, townships, and extra-parochial lower, Baglan, Baglan higher, Baglan lower, or other places following, or some of them (that Britton Ferry, Glyn Corwg Blaengwrach, Neath, is to say), Standishs Oxlinch. -

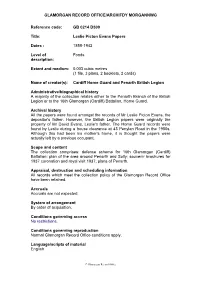

Reference Code: GB 0214 D509

GLAMORGAN RECORD OFFICE/ARCHIFDY MORGANNWG Reference code: GB 0214 D509 Title: Leslie Picton Evans Papers Dates : 1858-1942 Level of Fonds description: Extent and medium: 0.003 cubic metres (1 file, 3 plans, 2 booklets, 2 cards) Name of creator(s): Cardiff Home Guard and Penarth British Legion Administrative/biographical history A majority of the collection relates either to the Penarth Branch of the British Legion or to the 16th Glamorgan (Cardiff) Battalion, Home Guard. Archival history All the papers were found amongst the records of Mr Leslie Picton Evans, the depositor's father. However, the British Legion papers were originally the property of Mr David Evans, Leslie's father. The Home Guard records were found by Leslie during a house clearance at 43 Penylan Road in the 1980s. Although this had been his mother's home, it is thought the papers were actually left by a previous occupant. Scope and content The collection comprises: defence scheme for 16th Glamorgan (Cardiff) Battalion; plan of the area around Penarth and Sully; souvenir brochures for 1937 coronation and royal visit 1937; plans of Penarth. Appraisal, destruction and scheduling information All records which meet the collection policy of the Glamorgan Record Office have been retained. Accruals Accruals are not expected. System of arrangement By order of acquisition. Conditions governing access No restrictions. Conditions governing reproduction Normal Glamorgan Record Office conditions apply. Language/scripts of material English © Glamorgan Record Office Leslie Picton Evans Papers D509 Physical characteristics and technical requirements Fair condition Finding aids Detailed list available. Related units of description Glamorgan Home Guard records (ref. -

Trewallter Fawr, Walterston, Near Llancarfan, Vale of Glamorgan, CF62 3AS

Trewallter Fawr, Walterston, Near Llancarfan, Vale of Glamorgan, CF62 3AS Trewallter Fawr, Walterston Near Llancarfan, Vale of Glamorgan, CF62 3AS £795,000 Freehold 5 Bedrooms : 1 Bathrooms : 3 Reception Rooms An exceptional, Grade II* listed home to the very heart of the Vale offering extensive family accommodation and an immense wealth of character. Two large living rooms, both with open fires. Kitchen-breakfast room, scullery and garden room. Five bedrooms including a generous master bedroom. Includes a two-storey barn, outbuildings and large gardens, in all about 1.4 acres. Directions From our Cowbridge Office follow the A48 in an easterly direction towards Cardiff. Travel through Bonvilston, turning right at Sycamore Cross onto the A4226 ("Five Mile Lane") in the direction of Barry. Follow the road for close to 2 miles and turn right at the sign for Walterston. (This may involve some 'doubling back' whilst roadworks are being taken place). Follow this lane directly into the hamlet of Walterston, to find Trewallter Fawr to your left, set back behind a deep grass verge. A gated entrance leads into the yard to the side of the property, from which there is access to the property, to its gardens and to the barn. • Cowbridge 8.7 miles • Cardiff City Centre 10.1 miles • M4 (J33) 8.8 miles Your local office: Cowbridge T 01446 773500 E [email protected] Summary of Accommodation ABOUT THE PROPERTY * Located to the heart of the Vale yet within easy reach of Cardiff and Cowbridge * An exceptional, Grade II* listed property retaining -

Sustainable Settlements Apprai

Vale of Glamorgan Local Development Plan 2011 - 2026 Contents Page 1. Introduction 2 2. Context 3 3. Methodology 5 4. Initial Sustainability Rankings 12 5. Analysis 13 6. Conclusions 16 7. Use and Interpretation 20 Appendices Appendix 1 – Assessed Settlements Estimated Population 23 Appendix 2 – Vale of Glamorgan Revised Sustainable Settlements 25 Appraisal: Location and Boundaries of Appraised Settlements Appendix 3 – Vale of Glamorgan Revised Sustainable Settlements 26 Appraisal: Settlement Groupings Appendix 4 – Detailed Scoring of Settlements 27 Sustainable Settlements Apprai sal Review Background Paper 1 Vale of Glamorgan Local Development Plan 2011 - 2026 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Planning Policy Wales [PPW] (Fourth edition, 2011) requires Local Development Plans [LDPs] sustainable settlement strategies to be informed by an assessment of settlements to ensure they accord with the sustainable location principles contained within national planning policy (see PPW Section 4.6 Sustainable settlement strategy: locating new development). 1.2 As part of the evidence base for the Vale of Glamorgan LDP, the Council has undertaken an audit of services and facilities within the Vale of Glamorgan’s settlements in order to identify those which are potentially suitable to accommodate additional development in terms of their location, role and function. This assessment therefore forms part of the evidence base for the Vale of Glamorgan LDP Settlement Hierarchy by identifying broad groupings of settlements with similar roles and functions based upon the following research objectives: Objective 1: To assess the need for residents to commute beyond their settlement to access key employment, retail and community facilities (including education and health). Objective 2: To measure the general level of accessibility of settlements by sustainable transport. -

Why Aberthaw?

Why Aberthaw? The Aberthaw-Minehead tidal barrage location has five inherent benefits. This makes the location ideal for a 4,000 megawatt ‘green’ tidal power generating capability. (1) Electrical-power Generation The magnitude of the potential electrical-power generation capability is proportional to the product of the tidal height and the mass of water passing through a water-turbine. The Bristol Channel / Severn Estuary has the second highest tidal range in the world. At Lavernock Point the tidal range reaches about 14.5 metres in the Spring. At Aberthaw the tidal range reaches about 11.0 metres in the Spring. The magnitude and cyclic timing of the world’s tides are principally determined by the orbital path of the moon and the rotation of the earth. The gravitational forces produced during its transit cause any mass of water that is free to rise to do so and to attempt to move in the direction of the moon’s orbit. A narrowing west-to-east orientation of the channel into which it flows, such as the Severn Estuary, magnifies the resulting increase in level. The time taken for each tidal cycle varies. It is typically about 12 hours 20 minutes. Land-based hydro-generation often either replaces or works alongside waterfalls. The height through which the water falls dominates. In a choice of location, it is usually visually obvious where the maximum power generation potential exists. In tidal generation the tidal height changes simultaneously with the magnitude of the accompanying flow. The maximum power generation potential for a particular location is not immediately obvious.