Toni Braxton, Disney, and Thermodynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZALI Releases New Single "Girls Like Us" November 10Th

Oct 26, 2017 16:44 EDT ZALI releases new single "Girls Like Us" November 10th Los Angeles, CA - October 26, 2017 -- Irish Singer/Songwriter ZALI finds a new twist on losing love with her new single "Girls Like Us". She explores how women are not alone in the pain of rejection and heartbreak and will find a supportive sisterhood in the wake of heartbreak. Produced by the up-and-coming talented triple threat Keyboard Keith, with vocal production and engineering by renowned Irish producer James Darkin who has worked with artists like Hozier, Gavin James, Kanye West, Will.i.am and Rihanna, "Girls Like Us" showcases ZALI’s strength, both vocally and emotionally, as she performs her bold, unapologetic lyrics. With "Girls Like Us," ZALI has created an anthem for women, freeing them from their inhibitions, giving them permission to stop playing a role and to start getting exactly what they want. Inspired by artists like Amy Winehouse, Toni Braxton, Frank Ocean and Duffy, ZALI uses her music to tell stories and to capture the true emotion behind the music. "Girls Like Us’ for me is an anthem to girls everywhere to just let go and be. After previously recording the track earlier in the year, I went back into the Studio to re-record the track after just recently going through some heartbreak to really capture every emotion I was feeling and ‘Girls Like Us’ to me was a reaffirmation that I will be okay. And that there are no rules, except living my best life for me. What I want with my music is to create a bond between me and my listeners through our shared experiences," says ZALI about her creative process. -

Volume 1 Tracklist

VOLUME 1 TRACKLIST 1. Alicia Keys 26. Janet Jackson Showbiz Central 2. Ashton Kutcher 27. Justin Timberlake 3. Atomic Kitten 28. Katie Melua 4. Avril Lavigne 29. Kelly Clarkson 5. Basement Jaxx 30. Kelly Osbourne 6. Beverley Knight 31. Lemar 7. Bill Murray 32. LL Cool J 8. Billy Joel 33. Macy Gray 9. Blue 34. Madonna 10. Britney Spears 35. Melanie C 11. Cher 36. Ms Dynamite 12. Chesney Hawkes 37. Natalie Imbruglia 13. Craig David 38. Nelly 14. Daniel Bedingfield 39. Paul McCartney 15. Dannii Minogue 40. Rachel Stevens 16. David Schwimmer 41. Ricky Martin 17. Delta Goodrem 42. Samantha Mumba 18. Destiny’s Child 43. Scissor Sisters 19. Elton John 44. Sophie Ellis-Bextor 20. Eminem 45. Spice Girls 21. Faith Evans 46. Sting 22. Girls Aloud 47. Usher 23. Gwen Stefani 48. Vinnie Jones 24. Holly Valance 49. Will Smith 25. Jamie Oliver 50. Wyclef Jean www.bluerevolution.com/artistdrops VOLUME 2 TRACKLIST 1. 50 Cent 26. Lionel Richie Showbiz Central 2. Adam Sandler 27. Mariah Carey 3. Alanis Morisette 28. Maroon 5 4. Arnold Schwarzenegger 29. Mary J Blige 5. Ashanti 30. Missy Elliott 6. Beyoncé 31. Moby 7. Billy Idol 32. Natasha Bedingfield 8. Black Eyed Peas 33. Nelly Furtado 9. Christina Aguilera 34. Olsen Twins 10. Christina Milian 35. Outkast 11. Coldplay 36. Ozzy Osbourne 12. Cyndi Lauper 37. Pete Waterman 13. Daft Punk 38. Peter Andre 14. Darren Hayes (Savage Garden) 39. Phil Collins 15. David Bowie 40. Pink 16. Fatboy Slim 41. R Kelly 17. Hilary Duff 42. Ronan Keating 18. -

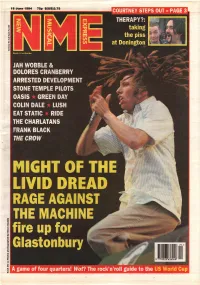

1994.06.18-NME.Pdf

INDIE 45s US 45s PICTURE: PENNIE SMITH PENNIE PICTURE: 1 I SWEAR........................ ................. AII-4-One (Blitzz) 2 I’LL REMEMBER............................. Madonna (Maverick) 3 ANYTIME, ANYPLACE...................... Janet Jackson (Virgin) 4 REGULATE....................... Warren G & Nate Dogg (Outburst) 5 THE SIGN.......... Ace Of Base (Arista) 6 DON’TTURN AROUND......................... Ace Of Base (Arista) 7 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY....................... Big Mountain (RCA) 8 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD......... Prince(NPG) 9 YOUMEANTHEWORLDTOME.............. Toni Braxton (UFace) NETWORK UK TOP SO 4Ss 10 BACK AND FORTH......................... Aaliyah (Jive) 11 RETURN TO INNOCENCE.......................... Enigma (Virgin) 1 1 LOVE IS ALL AROUND......... ...Wet Wet Wet (Precious) 37 (—) JAILBIRD............................. Primal Scream (Creation) 12 IFYOUGO ............... ....................... JonSecada(SBK) 38 38 PATIENCE OF ANGELS. Eddi Reader (Blanco Y Negro) 13 YOUR BODY’S CALLING. R Kelly (Jive) 2 5 BABYI LOVE YOUR WAY. Big Mountain (RCA) 14 I’M READY. Tevin Campbell (Qwest) 3 11 YOU DON’T LOVE ME (NO, NO, NO).... Dawn Penn (Atlantic) 39 23 JUST A STEP FROM HEAVEN .. Eternal (EMI) 15 BUMP’N’ GRIND......................................R Kelly (Jive) 4 4 GET-A-WAY. Maxx(Pulse8) 40 31 MMMMMMMMMMMM....... Crash Test Dummies (RCA) 5 7 NO GOOD (STARTTHE DANCE)........... The Prodigy (XL) 41 37 DIE LAUGHING........ ................. Therapy? (A&M) 6 6 ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS.. Absolutely Fabulous (Spaghetti) 42 26 TAKE IT BACK ............................ Pink Floyd (EMI) 7 ( - ) ANYTIME YOU NEED A FRIEND... Mariah Carey (Columbia) 43 ( - ) HARMONICAMAN....................... Bravado (Peach) USLPs 8 3 AROUNDTHEWORLD............... East 17 (London) 44 ( - ) EASETHEPRESSURE................... 2woThird3(Epic) 9 2 COME ON YOU REDS 45 30 THEREAL THING.............. Tony Di Bart (Cleveland City) 3 THESIGN.,. Ace Of Base (Arista) 46 33 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD. -

Black Women's Music Database

By Stephanie Y. Evans & Stephanie Shonekan Black Women’s Music Database chronicles over 600 Africana singers, songwriters, composers, and musicians from around the world. The database was created by Dr. Stephanie Evans, a professor of Black women’s studies (intellectual history) and developed in collaboration with Dr. Stephanie Shonekon, a professor of Black studies and music (ethnomusicology). Together, with support from top music scholars, the Stephanies established this project to encourage interdisciplinary research, expand creative production, facilitate community building and, most importantly, to recognize and support Black women’s creative genius. This database will be useful for music scholars and ethnomusicologists, music historians, and contemporary performers, as well as general audiences and music therapists. Music heals. The purpose of the Black Women’s Music Database research collective is to amplify voices of singers, musicians, and scholars by encouraging public appreciation, study, practice, performance, and publication, that centers Black women’s experiences, knowledge, and perspectives. This project maps leading Black women artists in multiple genres of music, including gospel, blues, classical, jazz, R & B, soul, opera, theater, rock-n-roll, disco, hip hop, salsa, Afro- beat, bossa nova, soka, and more. Study of African American music is now well established. Beginning with publications like The Music of Black Americans by Eileen Southern (1971) and African American Music by Mellonee Burnim and Portia Maultsby (2006), -

History of Super Bowl Halftime Entertainment

HISTORY OF SUPER BOWL HALFTIME ENTERTAINMENT SUPER BOWL HALFTIME I Universities of Arizona and Michigan Bands. II Grambling University. III “America Thanks” with Florida A&M University. IV Carol Channing. V Florida A&M Band. VI “Salute to Louis Armstrong” with Ella Fitzgerald, Carol Channing, Al Hirt and U.S. Marine Corps Drill Team. VII “Happiness Is…” with University of Michigan Band and Woody Herman. VIII “A Musical America” with University of Texas Band. IX “Tribute to Duke Ellington” with Mercer Ellington and Grambling University Bands. X “200 Years and Just a Baby” Tribute to America’s Bicentennial. XI “It’s a Small World” including crowd participation for first time with spectators waving colored placards on cue. XII “From Paris to the Paris of America” with Tyler Apache Belles, Pete Fountain and Al Hirt. XIII “Super Bowl XIII Carnival” Salute to the Caribbean with Ken Hamilton and various Caribbean bands. XIV “A Salute to the Big Band Era” with Up with People. XV “A Mardi Gras Festival.” XVI “A Salute to the 60’s and Motown.” XVII “KaleidoSUPERscope” (a kaleidoscope of color and sound). XVIII “Super Bowl XVIII’s Salute to the Superstars of the Silver Screen.” XIX “A World of Children’s Dreams.” XX “Beat of the Future.” XXI “Salute to Hollywood’s 100th Anniversary.” XXII “Something Grand” featuring 88 grand pianos, the Rockettes and Chubby Checker. XXIII “Be Bop Bamboozled” featuring 3-D effects. XXIV “Salute to New Orleans” and 40th Anniversary of Peanuts’ characters, featuring trumpeter Pete Fountain, Doug Kershaw & Irma Thomas. XXV “A Small World Salute to 25 Years of the Super Bowl” featuring New Kids on the Block. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the MIDDLE DISTRICT of NORTH CAROLINA GREENSBORO DIVISION Case No.: 1:06-Cv-00948-JAB-PTS

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA GREENSBORO DIVISION Case No.: 1:06-cv-00948-JAB-PTS ELEKTRA ENTERTAINMENT GROUP INC., ) a Delaware corporation; VIRGIN RECORDS ) AMERICA, INC., a California corporation; ) ARISTA RECORDS LLC, a Delaware limited ) liability company; BMG MUSIC, a New York ) general partnership; ATLANTIC RECORDING ) CORPORATION, a Delaware corporation; ) SONY BMG MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT, a ) Delaware general partnership; and ) INTERSCOPE RECORDS, a California general ) partnership, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) HARRISON HAYES, ) ) Defendant. ) DEFAULT JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT INJUNCTION Based upon Plaintiffs' Motion For Default Judgment, and good cause appearing therefore, it is hereby Ordered and Adjudged that: 1. Plaintiffs seek the minimum statutory damages of $750 per infringed work, as authorized under the Copyright Act (17 U.S.C. § 504(c)(1)), for each of the eleven sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint. Accordingly, having been judged to be in default, Defendant shall pay damages to Plaintiffs for infringement of Plaintiffs' copyrights in the 1 Case 1:06-cv-00948-JAB-PTS Document 13 Filed 03/12/07 Page 1 of 4 sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint, in the total principal sum of Eight Thousand Two Hundred Fifty Dollars ($8,250.00). 2. Defendant shall further pay Plaintiffs' costs of suit herein in the amount of Five Hundred Fifty Dollars ($550.00). 3. Defendant shall be and hereby is enjoined from directly or indirectly infringing Plaintiffs' rights -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1990S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1990s Page 174 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1990 A Little Time Fantasy I Can’t Stand It The Beautiful South Black Box Twenty4Seven featuring Captain Hollywood All I Wanna Do is Fascinating Rhythm Make Love To You Bass-O-Matic I Don’t Know Anybody Else Heart Black Box Fog On The Tyne (Revisited) All Together Now Gazza & Lindisfarne I Still Haven’t Found The Farm What I’m Looking For Four Bacharach The Chimes Better The Devil And David Songs (EP) You Know Deacon Blue I Wish It Would Rain Down Kylie Minogue Phil Collins Get A Life Birdhouse In Your Soul Soul II Soul I’ll Be Loving You (Forever) They Might Be Giants New Kids On The Block Get Up (Before Black Velvet The Night Is Over) I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Alannah Myles Technotronic featuring Robert Palmer & UB40 Ya Kid K Blue Savannah I’m Free Erasure Ghetto Heaven Soup Dragons The Family Stand featuring Junior Reid Blue Velvet Bobby Vinton Got To Get I’m Your Baby Tonight Rob ‘N’ Raz featuring Leila K Whitney Houston Close To You Maxi Priest Got To Have Your Love I’ve Been Thinking Mantronix featuring About You Could Have Told You So Wondress Londonbeat Halo James Groove Is In The Heart / Ice Ice Baby Cover Girl What Is Love Vanilla Ice New Kids On The Block Deee-Lite Infinity (1990’s Time Dirty Cash Groovy Train For The Guru) The Adventures Of Stevie V The Farm Guru Josh Do They Know Hangin’ Tough It Must Have Been Love It’s Christmas? New Kids On The Block Roxette Band Aid II Hanky Panky Itsy Bitsy Teeny Doin’ The Do Madonna Weeny Yellow Polka Betty Boo -

Diane Warren Is One of the Most Continuously Prolific and Successful Contemporary Songwriters of Our Time

mli^o=jrpf`=mofwb=i^rob^qb=OMOMW=af^kb=t^oobk= Diane Warren is one of the most continuously prolific and successful contemporary songwriters of our time. Her songs have been featured in more than 100 motion pictures, resulting in ten Oscar® nominations. She most recently wrote the original song “I’m Standing With You” performed by Chrissy Metz for the feature film Breakthrough. Her impressive career has garnered countless awards including an Emmy®, Grammy®, and a Golden Globe®. She has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and has been inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. Warren’s songs have charted in numerous countries and have sold over 250 million records worldwide. She has written 32 top-ten hits on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, nine of which have garnered the coveted No. 1 spot. To date, she is the only songwriter with more than one song listed amongst the top fifteen of Billboard’s The Hot 100’s All-Time Top 100 Songs. She writes songs for tremendously wide range of artists, and continues to work with many of today’s most popular acts, including Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, Adele, Justin Bieber, Christina Aguilera, Snoop Dogg, Kelly Clarkson, Carrie Underwood, Mary J. Blige, Jennifer Hudson, Paloma Faith, Andra Day, Demi Lovato, LeAnn Rimes, Common, Janelle Monae, Missy Elliott, Zendaya and Jason Derulo. She has written for iconic artists such as Whitney Houston, Cher, Aerosmith, Celine Dion, Aretha Franklin, Toni Braxton, Mariah Carey, and many more. Warren owns her own publishing company, Realsongs, the most successful female-owned and operated business in the music industry. -

The Biggest Hits of All: the Hot 100'S All-Time Top 100 Songs

The Biggest Hits of All: The Hot 100's All-Time Top 100 Songs billboard.com/articles/news/hot-100-turns-60/8468142/hot-100-all-time-biggest-hits-songs-list Adele, Rihanna, Ed Sheeran, Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Elton John, Chubby Checker, Mariah Carey, Shania Twain & Whitney Houston Getty Images; Photo Illustration by Quinton McMillan As part of Billboard's celebration of the 60th anniversary of our Hot 100 chart this week, we're taking a deeper look at some of the biggest artists and singles in the chart's history. Here, we revisit the ranking's 100 biggest hits of all-time. On Aug. 4 1958, Billboard launched the Hot 100, forever changing pop music -- or at least how it's measured. Sixty years later, the chart remains the gold-standard ranking of America's top songs each week. And while what goes into a hit has changed (bye, bye jukebox play; hello, streaming!), attaining a spot on the list -- or better yet, a coveted No. 1 -- i s still the benchmark to which artists explore, from Ricky Nelson on the first to Drake on the latest. Which brings us to the hottest-of-the-hot list the 100 most massive smashes over the charts six decades. 1/10 1. The Twist - 1960 Chubby Checker The only song to rule the Billboard Hot 100 in separate release cycles (one week in 1960, two in 1962), thanks to adults catching on to the song and its namesake dance after younger audiences popularized them. 2. Smooth - 1999 Santana Feat. Rob Thomas 3. -

VH1's Iconic Series "Behind the Music" Celebrates 15Th Anniversary Season with Eight New Episodes

VH1's Iconic Series "Behind The Music" Celebrates 15th Anniversary Season With Eight New Episodes FEATURED ARTISTS INCLUDE: TRAIN, NE-YO, CARRIE UNDERWOOD, NICOLE SCHERZINGER, GYM CLASS HEROES AND TONI BRAXTON AS WELL AS UPDATED EPISODES FEATURING T.I. AND P!NK New Season Premiering Sunday, September 16, 2012 at 9pm ET/PT VH1.com Expands the Franchise with Companion Series "Behind the Song" SANTA MONICA, Calif., Sept. 6, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- VH1's five-time Emmy Award-nominated documentary series "Behind The Music" returns to focus on eight of today's most influential icons in the music world. The series launches its landmark 15th year since inception with a roster of top artists including: NE-YO, Nicole Scherzinger, Gym Class Heroes, Toni Braxton, T.I. (updated), P!nk (updated) and the previously announced Carrie Underwood and Train. The franchise is also expanding on VH1.com with the addition of "Behind the Song," a companion series of original, standalone mini episodes where select artists discuss the inspiration behind a signature song. The new season will premiere Sunday, September 16, 2012 at 9pm ET/PT. "Behind The Music: TRAIN" Airs Sunday, September 16 at 9pm ET/PT "Behind The Music: Train" highlights the accomplishments of Pat Monahan, Jimmy Stafford, and Scott Underwood; a rock band from San Francisco, California formed in 1994. Train's original members Rob Hotchkiss and Charlie Colin, as well as Monahan, Stafford and Underwood achieved mainstream success with their debut album, Train, which was officially released in 1998 and was certified double platinum in the United States and Canada. -

Toni Braxton Download Album Music Love, Marriage & Divorce

toni braxton download album music Love, Marriage & Divorce. On Love, Marriage & Divorce, Toni Braxton and Babyface, creative partners going back to the early '90s, rekindle their musical relationship. Both endured broken marriages, and presumably it's those experiences that inform the material here -- a succinct collection of 11 songs, eight of which are duets. The emphasis is on divorce, indicated from the very beginning on "Roller Coaster," where Babyface enters with "Today I got so mad at you, it's like I couldn't control myself." The set finishes with the bittersweet "The D Word," seemingly a Sade homage, in which Babyface confesses "You still own my heart, forever and ever and ever." Moments that deviate from issues of romantic strife are few. The duo don't seem nearly as connected to them. "Sweat," a slinking groove, is like the "Love During War" to Robin Thicke's "Love After War," while "Heart Attack," near the album's end, is a retro-disco move that seems more like a throw-in than a crucial part of the album. The sequence of songs plays out like scenes on shuffle. Either that, or the relationship is extremely up and down; the singers sometimes sound as if they are addressing ex-lovers from other relationships. "Reunited" is a blissful ballad, but it's followed by the embittered "I'd Rather Be Broke," where Braxton asserts, "Just because your money's strong don't mean you can do the things that you do." Babyface is civil and clear-headed on "I Hope That You're Okay," claiming he "can't go through the motions anymore," but Braxton follows with a solo spotlight, "I Wish," that seems drawn from a different situation: "I hope she creeps on you with somebody who is 22/I swear to God, I'm gonna be laughing at you every day." As a narrative, the album can be hard to follow, but it's not as if breakups have a simple arc with a steady, unwavering decline. -

Brown Sugar Repertoire – Updated May 2021

REPERTOIRE No Song Title Artist Name Ballad or Dancing Select 1 Dance Wit Me 112 Dancing 2 Only You (Remix) 112 Dancing 3 Boogie Oogie A Taste Of Honey Dancing 4 Make Me Whole Amel Lerrieux Ballad 5 What’s Come Over Me Amel Lerriex & Glenn Lewis Ballad 6 Let’s Stay Together Al Green Ballad or Dancing 7 Fallin' Alicia Keys Ballad 8 If I Ain’t Got You Alicia Keys Ballad 9 No One Alicia Keys Ballad 10 You Don’t Know My Name Alicia Keys Ballad 11 How Come You Don’t Call Me Alicia Keys Ballad 12 I Swear All 4 One Ballad 13 Consider Me Allen Stone Ballad 14 Taste Of You Allen Stone Dancing 15 Make It Better Anderson .Paak Ballad 16 Leave The Door Open Anderson .Paak | Bruno Mars Ballad 17 Valerie Amy Winehouse Dancing 18 Best Of Me Anthony Hamilton Ballad 19 You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman Aretha Franklin Ballad 20 Respect Aretha Franklin Dancing 21 I Say A Little Prayer Aretha Franklin Ballad 22 Until You Come Back to Me Aretha Franklin Ballad 23 Rock Steady Aretha Franklin Dancing 24 Side To Side Ariana Grande Dancing 25 People Everyday Arrested Development Dancing 26 Foolish Ashanti Ballad 27 Nothing On You B.O.B & Bruno Mars Dancing 28 Change The World Babyface Ballad 29 Whip Appeal Babyface Ballad 30 Every time I Close My Eyes Babyface Ballad 31 Can’t Get Enough Of Your Love Baby Barry White Dancing 32 How Deep Is Your Love Bee Gees Ballad 33 Poison Bel Biv Devoe Dancing 34 Love on Top Beyoncé Dancing 35 Déjà vu Beyoncé Dancing 36 Work It Out Beyoncé Dancing 37 Crazy In Love Beyoncé Dancing 38 Halo Beyoncé Ballad 39 Irreplaceable