Resolving the Paradox of the Enlightenment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper and Poster Abstracts for History of Science Society Meeting – 2014

Paper and Poster Abstracts for History of Science Society Meeting – 2014 Abstracts are sorted by the last name of the primary author. Author: Fredrik Albritton Jonsson Title: Coal Futures 1789-1884 Abstract: Long before William Stanley Jevons’ The Coal Question (1865), mining engineers and natural historians sought to calculate the extent of the British coal reserves. Centennial and millennial time scales entered Victorian politics in the 1830s through debates on coal exhaustion. Coal husbandry was theorized by geologists and political economists as a problem of intergenerational equity and became the subject of policy in the case of coal tariffs. After 1870, John Ruskin developed a vision of adverse anthropogenic climate change, linked to deforestation, agriculture, glacial contraction, and coal use. In short, politicians, intellectuals, and scientists increasingly began to see industrial Britain as a carbon society, subject to unprecedented environmental pressures. Author: Janet Abbate Title: From Handmaiden to “Proper Intellectual Discipline”: Computer Science, the NSF, and the Status of Applied Science in 1960s America Abstract: From the mid-1950s to 1970, relations between academic computer scientists and the National Science Foundation underwent a significant shift. Initially regarded by NSF as merely a tool to support the more established sciences, computer science rapidly became institutionalized in university departments and degree programs in the early 1960s, and NSF responded by creating an Office of Computing Activities in 1967 to fund research and education as well as facilities. Since funding is essential to the practice of science as well as a signifier of disciplinary power and status, acquiring a dedicated government funding stream was a remarkable coup for such a young field. -

ARIFMOMETR1 an Archaeology of Computing in Russia Georg Trogemann Alexander Nitussov Wolfgang Ernst

Editorial and Historical Introduction ARIFMOMETR1 An Archaeology of Computing in Russia Georg Trogemann Alexander Nitussov Wolfgang Ernst The genealogy of the computer and computing sciences as associated with names such as Charles Babbage, Alan Turing, Norbert Wiener, Heinz v. Foerster, Claude Shannon and John v. Neumann has been the object of an impressive number of media- archaeological publications in the German-speaking and Anglo-American areas, but in general the historiography of computing is - even a decennium after the fall of the Iron Curtain - still blind in respect to Eastern Europe. This is why the combined research and publication project Arifmometr, carried out by the Academy of Media Arts in Cologne in co-operation with institutions in the former Soviet Union, tries to evaluate the role which Russia played in contributing to the development of the medium computer in comple- mentary or alternative ways on both technical and cultural horizons. Furthermore, in reconstructing the Russian case, emphasis has been put on the relationship between mathematical and cybernetic thinking on the one hand, and social, economical and poli- tical models on the other. The Historiography of Computing and Archival Evidence The introduction to one of the few articles in English which have previously been published on Soviet computer archaeology, prompted by the International Research Conference on the History of Computing at Los Alamos (New Mexico) in June 1976, is characteristic for the nature of research: ” Based on publications, personal reminiscences and the author´s own archives, this historical paper attempts to analyze the first 15 years of the formation and development of computer programming in the USSR.”2 What is missing here is the level of institutional archival evidence. -

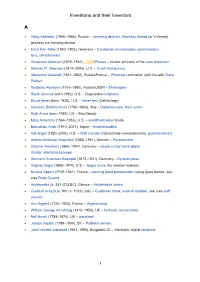

Inventions and Their Inventors A

Inventions and their Inventors A Vitaly Abalakov (1906–1986), Russia – camming devices, Abalakov thread (or V-thread) gearless ice climbing anchor Ernst Karl Abbe (1840–1905), Germany – Condenser (microscope), apochromatic lens, refractometer Hovannes Adamian (1879–1932), USSR/Russia – tricolor principle of the color television Samuel W. Alderson (1914–2005), U.S. – Crash test dummy Alexandre Alexeieff (1901–1982), Russia/France – Pinscreen animation (with his wife Claire Parker) Rostislav Alexeyev (1916–1980), Russia/USSR – Ekranoplan Randi Altschul (born 1960), U.S. – Disposable cellphone Bruce Ames (born 1928), U.S. – Ames test (Cell biology) Giovanni Battista Amici (1786–1863), Italy – Dipleidoscope, Amici prism Ruth Amos (born 1989), UK – StairSteady Mary Anderson (1866–1953), U.S. – windshield wiper blade Momofuku Ando (1910–2007), Japan – Instant noodles Hal Anger (1920–2005), U.S. – Well counter (radioactivity measurements), gamma camera Anders Knutsson Ångström (1888–1981), Sweden – Pyranometer Ottomar Anschütz (1846–1907), Germany – single-curtain focal-plane shutter, electrotachyscope Hermann Anschütz-Kaempfe (1872–1931), Germany – Gyrocompass Virginia Apgar (1909–1974), U.S. – Apgar score (for newborn babies) Nicolas Appert (1749–1841), France – canning (food preservation) using glass bottles, see also Peter Durand Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC), Greece – Archimedes' screw Guido of Arezzo (c. 991–c. 1033), Italy – Guidonian hand, musical notation, see also staff (music) Ami Argand (1750–1803), France – Argand lamp William George Armstrong (1810–1900), UK – hydraulic accumulator Neil Arnott (1788–1874), UK – waterbed Joseph Aspdin (1788–1855), UK – Portland cement John Vincent Atanasoff (1903–1995), Bulgaria/U.S. – electronic digital computer 1 Inventions and their Inventors B Charles Babbage (1791–1871), UK – Analytical engine (semi-automatic) Tabitha Babbit (1779–1853), U.S. -

Origin and Interaction of Mathematics and Mechanics

Jan Awrejcewicz Vadim A. Krysko Origin and Interaction of Mathematics and Mechanics Jan Awrejcewicz Technical University of Łódź Department of Automatics and Biomechanics 1/15 Stefanowskiego St. 90-924 Łódź, Poland e-mail: [email protected] www.p.lodz.pl/k16 Vadim A. Krysko Saratov State Technical University Department of Higher Mathematics 77 Polytechnicheskaya St. 410054,Saratov, Russia e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 83-911746-7-0 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Department of Automatics and Biomechanics, 1/15 Stefanowskiego St. 90-924 Łódź, Poland), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of informa- tion storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to property rights. © Department of Automatics and Biomechanics Press, 2007. Printed in Poland Publisher: Department of Automatics and Biomechanics, The Technical University of Łódź, 1/15 Stefanowski St., 90-924 Łódź, Poland Cover design: Marek Kaźmierczak Contents Foreword .............................................................................................1 1. The Beginning ..........................................................................7 -

100 Russian Engineers Who Changed Our Life 100 RUSSIAN ENGINEERS WHO CHANGED OUR LIFE

100 Russian Engineers Who Changed Our Life 100 RUSSIAN ENGINEERS WHO CHANGED OUR LIFE Moscow 2014 Dear Reader, The book you are holding in your hands is today more relevant than ever. It is unlikely that anyone would doubt Russia’s need in highly skilled engineers. The country requires a breakthrough in science and technology. This means that the time has come to bet on innovative development, drawing on the rich history of Russian engineering. For a number of centuries Russia enjoyed undisputed leadership in science and engineering breakthroughs. Its scientists and inventors were pioneers in many branches of science and technology. The discoveries they made changed our world, creating a new reality, earning admiration for our country and respect as a superpower. The main goal of this book is to remind people of the outstanding contributions our engineers have made towards the progress of science and technology, to teach the younger generations about Russian history and to tell them how interesting engineering can be. The generation of the 21 st century should know about our compatriots, whose inventions and discoveries made such great contributions to human knowledge, and they should strive to meet or surpass those achievements. Despite the unquestionable difficulties of modern Russian industry, the professions of engineers, designers, and science workers are still prestigious and in demand. Developing unique technologies, constantly refining them and looking for new solutions expands the limits of the possible, making the future a reality today; those are the traditional principles our brilliant engineers were guided by. These same principles should also be the basis of how work is organised in any modern company. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 24 March 2016 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Tyulenev, S. (2015) 'Resolving the paradox of the Enlightenment.', Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities social sciences., 8 (2). pp. 308-328. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.17516/1997-1370-2015-8-2-308-328 Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Sergey Tyulenev School of Modern Languages and Cultures Durham University Resolving the Paradox of the Enlightenment Abstract The focus of this article is on the role of translation in the Westernisation of eighteenth-century Russia. The emphasis is placed on the integration of Russian science into the European global science function system (Luhmann). In the global science system, translation played a part in resolving the paradox of the Enlightenment agenda, which was how to make possible the exchange of knowledge in the scholarly community (mainly in Latin), and at the same time make that knowledge accessible to any other, non-academic, linguistic community (in Russian).