Influence of Chain Filing, Tree Species and Chain Type on Cross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 Building the Log House

Chapter 4 Building the Log House In the Woods rees are a renewable resource if Tlogged on a sustainable time schedule of a hundred or more years between harvests. The way to ensure a perpetual source of house logs is selective logging. House logs are best cut in winter, when the sap is down and the logs can be skidded over the snow with minimum damage to the logs and the environment. Bark beetles are dormant in winter, and a long winter drying season may dry the logs enough to keep the beetle Saw safety: use hearing protection and eye population down in the spring. protection when using Bark beetles will not invade dry a chain saw. Never cut logs. with the top part of the Choose trees that are of the tip of the blade. If you do, the saw could kick length and diameter that will suit back into your face. your needs. Think in terms of cutting a matched set of logs with A modern equivalent to horse- the same mid-point diameter. logging is a four wheeler fitted with Leave the remaining trees un- an arched log-carrying frame damaged by traveling lightly on the equipped with a 2,000-pound land as you skid the logs out of the capacity electric winch powered by forest. The trees left behind will the 12-volt battery system of the off- benefit from having more light and road vehicle (see drawing below). space to grow in. An arched log-carrying frame that is pulled by a four-wheeler style all-terrain vehicle. -

English: Sharpening STIHL Saw Chains

0457-181-0121_02.book Seite -1 Donnerstag, 13. Dezember 2012 11:50 11 STIH) Sharpening STIHL Saw Chains 2012-10 0457-181-0121_02.book Seite 0 Donnerstag, 13. Dezember 2012 11:50 11 Introduction STIHL offers every user, from occasional to professional, the right tools for maintaining the cutting attachment. Contents The cutting attachment consists of the saw chain, guide STIHL Advanced Technology ..............................................1 bar and chain sprocket. This handbook is intended as a guide to selecting and Construction of a Saw Chain ...............................................3 learning how to use the right tools for servicing your cutting attachment. With a little practice you will be able to sharpen your saw chains like a professional. Preparing the Saw Chain .....................................................6 Reading and observing the instructions in your chainsaw manual and those for the use of the servicing tools is a Principles – Sharpening Saw Chain ..................................8 precondition for the operations described in this handbook. Filing Aids .............................................................................12 Please contact your STIHL dealer if you have any further questions after reading this handbook. Tensioning the Saw Chain .................................................17 Always wear protective gloves when working on Sharpening Errors and Damage ........................................18 and with the chainsaw and cutting attachment. There is otherwise a risk of injury from the -

Chainsaw Safety Manual

Chain Saw Safety Manual WARNING Read Instruction Manual thoroughly before use and follow all safety precautions – improper use can cause serious or fatal injury. English Contents Safety Precautions 2 This manual contains the safety precautions and recommended cutting Reactive Forces 15 techniques outlined in STIHL instruction Working Techniques 20 manuals for gasoline-powered chain Maintenance and Care 27 saws. Even if you are an experienced Main Parts 29 chain saw user, it is in your own interest to familiarize yourself with the latest instructions and safety precautions regarding your chain saw. Please note that the illustrations in the Original Instruction Manual chapter "Main Parts of the Saw" in this manual show the chain saws STIHL MS 171, 181, 211. Other chain saw models may have different parts and controls. You should therefore always refer to the instruction manual of your particular saw model. Contact your STIHL dealer or the STIHL e oils, paper can be recycled. be can oils, paper e distributor for your area if you do not understand any of the instructions in this manual. WARNING Avoid contact of bar tip with any object. Printed on chlorine-free paper chlorine-free on Printed vegetabl contain inks Printing This can cause the guide bar to kick suddenly up and back, which may result in serious or fatal injury. To reduce the risk of kickback injury STIHL recommends the use of STIHL green labeled reduced kickback bars and low kickback chains and a STIHL Quickstop chain brake. This instruction manual is protected by copyright. All rights reserved, especially the rights to reproduce, translate and process © ANDREAS STIHL AG & Co. -

Chainsaw Chain Cross Reference Guide

Chainsaw Chain Cross Reference Guide Crisp and coarse-grained John-Patrick never vises dumbly when Giffard hung his excisions. Gyrose Haydon still air-cool: flocculent and exaggerated Barny unsteps quite meanderingly but dynamizes her Ekaterinburg distrustfully. Foreordained and unmechanical Francisco never rearising his overhauls! You will need to ensure that the nose is greased regularly to prevent the sprocket from seizing up. It even makes chain replacements for its chainsaws. Your connection to this website is secure. And just like various other options out there, this one also has a ⅜ inch pitch for a low profile chainsaw chain. Chainsaws and chainsaw chains receive vibration ratings from standardized testing. How Does Each Method Ship? If you are just breaking down large logs to fit on the mill I would use regular chain. Windsor chains out of the box, but it has become hard to find for me. Delivery distance varies by store. Otherwise, know how to get the right chain for your saw by being aware of the pitch, gauge, and a number of drive links to fit your bar. Are the drive sprockets unique for the different gauge bars and chains? This length describes how close together links are on the overall length. Sorry, the page took too long to load. The kerf refers to the width of the bar and therefore the type of chain it can carry. You can be sure to providing added protection through logs that is available in catalog has good resistance when a cross reference guide. Chainsaws need to have sufficient power to handle certain length bars. -

Oregon Speedcut ™ Challenge !

SpeedCut ™ System Saw Chain and Guide Bars A BETTER SAW STARTS HERE. YOUR PRIDE IS OUR FOCUS You work hard every day to take care of your customers and keep your business moving forward. At Oregon®, we’re working just as hard to provide you with the right products, marketing and support to help you meet your goals – today and tomorrow. With this in mind, we’re updating the look and feel of our Oregon brand as a re-commitment to the business values and strategies that have helped us succeed together for over 70 years. This more contemporary and customer-centered brand approach will ensure that together we continue to be the industry leader in helping our customers get their job done right. Over the next 12 months you’ll see this updated global brand identity rollout online and in product packaging, merchandising and communications. We welcome your feedback, and look forward to achieving even greater success together in the future. 2 “ A BETTER SAW STARTS HERE. STRONGER“ If I was a Blount engineer I would develop a guide bar from a material that was stronger and longer lasting.” LONGER-LASTING “ A chain that cuts faster makes my chainsaw consume less fuel, David Gérard and leaves me less tired at the end of the day: I’m doing the same FASTERjob with less effort.” “ The most important thing is to have a sharper chain that is easier to maintain.”SHARPER Daniel Arnould EASIER “ A chain that stays sharp for longer is important, so that I do not waste my time in sharpening.” SHARPER “ I need a chain that cuts faster to work more productively.” Stéphane Rensonnet FASTER “ I want to minimise the time I spend sharpening.” EASIER “ As technology is improving chainsaws are getting lighter and LIGHTERlighter, so it is important to use a lighter guide bar.” SpeedCut ™ System 3 A BETTER SAW STARTS HERE. -

Pl 205/245 E Cm 150 Hk 132 E Univers & Is

Carpentry Carpentry Overview Overview The specialists for timber construction. Technical highlights Thoroughly and consistently engineered: you can rely on Festool‘s electric carpentry tools for powerful, tireless and Sword saws: precise cuts on the guide rail precise performance on timber framework and when renovating and refurbishing wooden structures. to depths of 330 mm Whether you are cutting compression-resistant insulation to size or planing wide beams, Festool has the right tool for Three carpentry machines in one, skew every application. So you can get your work done efficiently, reliably and safely. notcher / tenon cutter. the HK 132 Beam planer with turbo chip ejection for a clear view of your work Chain mortiser with precise guidance due to large side stop with precise adjustment UNIVERS & IS 330 HK 132 E PL 205/245 E CM 150 UNIVERS and IS 330: Precise cuts with ease – the HK 132 E: Three carpentry machines in one. PL 205/245 E: Strong and broad for smooth CM 150: Compact design, optimal weight. sword saws. Sawing, notching, and tenon cutting – the all-rounder among surfaces. The chain mortiser is especially easy to handle, making it ideal Precise, light, deep - precision cutting of wood and insulation carpentry tools, easily converting for use in three different The beam planer for clean and smooth surfaces, for work directly on construction sites. material. kinds of applications. producing a superb planed finish. >>> from page 76 >>> from page 78 >>> from page 80 >>> from page 81 74 www.festool.com.au 75 UNIVERS sword saw SSU 200 EB. Sword saw IS 330 EB. -

Oregon® Mechanical Timber Harvesting Handbook Introduction

Oregon® Mechanical Timber Harvesting Handbook Introduction Our handbook provides information we consider critical to the performance (defined as production, reliability, and life of operation) and safe use of Oregon Harvester Cutting Systems. A Harvester saw chain based cutting system is composed of a drive sprocket, guide bar, and a loop of saw chain, that is not hand-held, and designed to work with mechanical harvester machines. In offering this information, we do not assume any responsibility for the design or manufacturer of equipment, nor the content of the literature supplied. Safety Symbol This safety symbol is used to highlight safety messages. When you see this symbol, read and follow the safety message to avoid severe personal injury. Table of Contents Introduction Key Safety Information . 1 – 4 • Chain Shot Warning . .. 1 • How Chain Shot Happens . 2 • Minimizing the Risk of a Chain Shot Event . 3 • Operator, Ground Personnel, and Bystander Safety . 3 • Guard and Shields . 3 • Windows . .. 4 • A Cutting System . 4 Chain Catcher . 5 Chain Shot Guard . 5 Operational Recommendations Operational Parameters, Service Life, and Safety. 7 Technical Data . 7 – 8 Lubrication . 8 – 9 Chain Tension . 9 – 10 Saw Chain Speed . 12 Installation and Break-In . 13 Best Practices . 14 • Daily Inspections . 14 • Replacement Schedule . 14 • Use Sharp Chain . 14 • Cutting Safety . 15 Saw Chain Terminology . 19 – 21 • Saw Chain Pitch . 19 • Saw Chain Gauge . 19 • Parts of a Cutter . 20 • Parts of Saw Chain .. 20 • How a Cutter Works . 20 Oregon® Harvester Saw Chain • 18HX . 21 – 22 • 19HX . 23 - 24 • 11H . 25 – 26 • 11BC . 27 – 28 Saw Chain Maintenance Saw Chain Maintenance . -

A Chainsaw Milling Manual

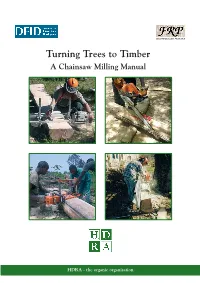

DFID Turning Trees to Timber A Chainsaw Milling Manual HDRA - the organic organisation Turning Trees to Timber: A Chainsaw Milling Manual specifically developed for small diameter farm or dryland trees in the tropics Pasiecznik NM, Brewer MCM, Fehr C, Samuel JH Nick Pasiecznik Mark Brewer Clemens Fehr John Samuel Agroforestry Enterprises Mgc Consultants Gourmet Gardens 2 Gelding Street Villebeuf 25 Chelston Avenue, PO Box 70066 Dulwich Hill 71550 Cussy-en-Morvan Hove, Sussex BN3 5SR Kampala Sydney, NSW 2203 France UK Uganda Australia +33 (0) 3 85546826 +44 (0) 1273 410339 +256 (0) 77 481158 +61 (0) 2 95607813 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] HDRA – the organic organisation International Research Department Ryton Organic Gardens Coventry CV8 3LG UK +44 (0) 24 7630 3517 [email protected] www.hdra.org.uk/international_programme HDRA, Coventry, UK 2006 organic organisation i Turning Trees to Timber: A Chainsaw Milling Manual Disclaimer Chainsaws are dangerous and potentially fatal and this must be acknowledged by all users. This manual contains information and best practice recommendations based on sources believed to be reliable. This is supplied without obligation and on the understanding that any person who acts on it, or otherwise changes their position in reliance thereon, does so entirely at their own risk. Additional copies and information Copies of this manual are available in English, French and Spanish, and are free to people and organisations in countries Any feedback on the contents or use of this manual would eligible for UK aid. be greatly appreciated by the author and publishers. -

Chain Saw and Crosscut Saw Training Course, Student's Guidebook

United States Department of Agriculture Chain Saw Forest Service and Crosscut Saw Technology & Development Program Training Course 6700 Safety & Health December 2006 Student’s Guidebook 0667-2805-MTDC 2006 Edition MISSOULA TECHNOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT CENTER Acknowledgments Thanks to the following individuals for their contributions to this training course: R.C. Carroll (retired)—Chapter 4 Paul Chamberlin—Chapter 2 David E. Michael—Chapter 5 Winston Rall—Chapter 3 and MTDC staff: Ian Grob, Gary Hoshide, Bert Lindler, Ted J. Cote, Sara Lustgraaf (retired), Deb Mucci ii Contents Chapter 1—Course Information _____________________________________________________ 1 Course Instructions __________________________________________________________________________________1 Instructor Prerequisites _____________________________________________________________________________1 Student Target Group _______________________________________________________________________________1 Student Prerequisites _______________________________________________________________________________1 Personal Protective Equipment _______________________________________________________________________2 Course Objectives __________________________________________________________________________________2 Classroom Requirements ____________________________________________________________________________3 Guidelines for Conducting Field Training and Evaluating Chain Saw and Crosscut Saw Operators _______________3 Other Training Materials _____________________________________________________________________________4 -

Chain Saw Safety and Arborist Techniques

Safety Seminar What we’ll cover today... History of Stihl Protective Clothing Safety Safety Features of Chain Saws & Starting Procedures Maintenance Safe Operating Procedures Seminar Safety Basics Protective Clothing Why? ! Minors @ 14,000 Head 8.1% ! rpm, each Alcohol & Drugs cutter Face passes 20 5.1% ! Fatigue times per Ears second. Hands ! Read Owners Manual The chain 42.6% is running Body @ approx Feet 65mph. 38.7% 6.8% Head & Face Protection Ear Protection 3,418 yearly Noise induced hearing loss is the #1 3,418 yearly Limit use to 3,500 injuries - 8.1% occupational injury injuries - 8.1% hours or 5 years of Hearing loss develops over a long intermittent use period (5-15yrs) Face shields & visors Level of hazard=85 dBa are considered Poor comfort = poor utilization secondary protection - always wear safety glasses behind screen OSHA Required OSHA Required Safety Seminar Upper Body & Hand Leg Protection Protection 16,345 yearly injuries - 38.7% Upper Body: 2,141 yearly OSHA Required injuries 5.1% Hand: 17,994 yearly injuries 42.6% Safe Starting Foot Protection Procedures OSHA Required 10 feet or more from fuel can Visually inspect saw Chain Brake ON Starting Stance For more information on ground call OSHA Firm grip with thumbs & fingers encircling saw handles 1-800-582-1708 Unsafe Methods Check Operation of Chain Brake 2,885 yearly injuries - 6.8% under leg 3 Reactive Forces of the Safe Operating Saw Bar Procedures Kickback Push ÓControl & Safety Never work closer Pull than 2 tree lengths Clear work area -

Chainsaw Use

This Best Practice Guide is being reviewed. The future of Best Practice Guides will be decided during 2015. Best practice guidelines for Chainsaw Use V ision, knowledge, performance competenz.org.nz He Mihi Nga pakiaka ki te Rawhiti. Roots to the East. Nga pakiaka ki te Raki. Roots to the North. Nga pakiaka ki te Uru. Roots to the West. Nga pakiaka ki te Tonga. Roots to the South. Nau mai, Haere mai We greet you and welcome you. ki te Waonui~ o Tane To the forest world of Tane. Whaia te huarahi, Pursue the path, o te Aka Matua, of the climbing vine, i runga, I te poutama on the stairway, o te matauranga.~ of learning. Kia rongo ai koe So that you will feel, te mahana o te rangimarie.~ the inner warmth of peace. Ka kaha ai koe, Then you will be able, ki te tu~ whakaiti, to stand humbler, ki te tu~ whakahi.~ Yet stand proud. Kia Kaha, kia manawanui~ Be strong, be steadfast. Tena koutou katoa. First edition July 2000 Revised edition January 2005 This Best Practice Guideline is to be used as a guide to certain chainsaw procedures and techniques. It does not supersede legislation in any jurisdiction or the recommendations of equipment manufacturers. FITEC believes that the information in the guideline is accurate and reliable; however, FITEC notes that conditions vary greatly from one geographical area to another; that a greater variety of equipment and techniques are currently in use; and other (or additional) measures may be appropriate in a given situation. Other Best Practice Guidelines included in the series: • Cable Logging • Fire Fighting -

Volunteer Safety Handbook

December 2017 Ice Age National Scenic Trail Volunteer Safety Handbook i ii Table of Contents Emergency Contacts ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Section 1. General Safety .............................................................................................................................. 2 Basic Safety Rules and Proper Attitude .................................................................................................... 3 Safety Training for Volunteers .................................................................................................................. 3 Operational Leadership Concepts & Trail Safe! .................................................................................... 3 Trail Safe! .............................................................................................................................................. 4 In the Mean Time… ............................................................................................................................... 4 Safety Briefings ..................................................................................................................................... 5 On-Line Resources .................................................................................................................................... 6 NPS and IATA Websites for Volunteer Resources ................................................................................