Gibraltar General Election 17Th October 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hearing on the Report of the Chief Justice of Gibraltar

[2009] UKPC 43 Privy Council No 0016 of 2009 HEARING ON THE REPORT OF THE CHIEF JUSTICE OF GIBRALTAR REFERRAL UNDER SECTION 4 OF THE JUDICIAL COMMITTEE ACT 1833 before Lord Phillips Lord Hope Lord Rodger Lady Hale Lord Brown Lord Judge Lord Clarke ADVICE DELIVERED ON 12 November 2009 Heard on 15,16, 17, and 18 June 2009 Chief Justice of Gibraltar Governor of Gibraltar Michael Beloff QC Timothy Otty QC Paul Stanley (Instructed by Clifford (Instructed by Charles Chance LLP) Gomez & Co and Carter Ruck) Government of Gibraltar James Eadie QC (Instructed by R J M Garcia) LORD PHILLIPS : 1. The task of the Committee is to advise Her Majesty whether The Hon. Mr Justice Schofield, Chief Justice of Gibraltar, should be removed from office by reason of inability to discharge the functions of his office or for misbehaviour. The independence of the judiciary requires that a judge should never be removed without good cause and that the question of removal be determined by an appropriate independent and impartial tribunal. This principle applies with particular force where the judge in question is a Chief Justice. In this case the latter requirement has been abundantly satisfied both by the composition of the Tribunal that conducted the initial enquiry into the relevant facts and by the composition of this Committee. This is the advice of the majority of the Committee, namely, Lord Phillips, Lord Brown, Lord Judge and Lord Clarke. Security of tenure of judicial office under the Constitution 2. Gibraltar has two senior judges, the Chief Justice and a second Puisne Judge. -

Monday 16Th December 2019

P R O C E E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T AFTERNOON SESSION: 3.34 p.m. – 6.19 p.m. Gibraltar, Monday, 16th December 2019 Contents Prayer ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Confirmation of Minutes .................................................................................................................. 3 Communications from the Chair ...................................................................................................... 3 Recognition of Hon. K Azopardi as Her Majesty’s Leader of the Opposition .......................... 3 Papers to be laid ............................................................................................................................... 3 Announcements ............................................................................................................................... 4 UK General Election result and Brexit – Statement by the Chief Minister ............................... 4 Questions for Oral Answer ................................................................................................... 11 Housing, Youth and Sport ............................................................................................................... 11 Q149/2019 Victoria Stadium floodlights – Responsibility for maintenance .......................... 11 Q150/2019 Newly built sports facilities – Outstanding remedial works and completion ..... 12 Q151/2019 -

Minding Gibraltar’S Business Intouch 1 CONTENTS

Issue 22 - Winter 2013 iMindingntouch Gibraltar’s Business Interview with the Minister for Financial Services Frontier Issues Centre of Digital Innovation & Incubation Small Business Saturdays Developing Local Media Health & Safety Seminar www.gfsb.gi Minding Gibraltar’s Business intouch 1 CONTENTS Issue 22 - Winter 2013 iMindingntouch Gibraltar’s Business Contents InTouch | Issue 22 | Winter 2013 GFSB Editor’s Notes 05 Meet the Board 06 Chairman’s Notes 07 GFSB’s Chair Gemma Vasquez interviews the Minister for www.gfsb.gi 08 Minding Gibraltar’s Business intouch 1 Financial Services, Albert Isola Zen and the art of Gibraltar frontier queuing 12 Federation of Small Businesses The UK’s Leading Business Organisation Frontier issues 14 Cross-border group signs ‘historical declaration’ against 15 frontier problems Developing Gibraltar’s first centre of Digital Innovation 16 & Incubation GFSB launches Small Business Saturdays 18 Glocon - wearable technology of the future 20 New to Gibraltar - Aphrodite Beauty Academy 22 intouch Greenarc goes green! 24 Editorial Director Medport Shipping - Making a name for themselves 26 Julian Byrne Content is King- Truth or Myth? 28 Designed by Piranha Designs Gibraltar An Effective Workplace 30 www.piranhadesigns.com Developing local media 32 Published by Economic benefits from filming locations and tourism 34 The GFSB Health & Safety seminar highlights need for risk assessments 36 122 Irish Town Gibraltar Calentita: GFSB Rockchef stall 38 Tel: +350 200 47722 Fax: +350 200 47733 Email: [email protected] www.gfsb.gi Disclaimer No part of this publication may be reproduced without the wirtten permission of the publishers. The Publishers and the Editor have made every effort to ensure that all of the information within this publication is accurate, but emphasise that they cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions. -

GSD Manifesto 2019

GIBRALTAR SOCIAL DEMOCRATS / ELECTION MANIFESTO 2019 4 Gibraltar Social Democrats - Manifesto 2019 OUR CORE COMMITMENTS GIBRALTAR 2050 A 30 Year Strategic Plan for Planning & Development so that there is a long term vision for a sustainable environmental and economic future. QUALITY OF YOUR LIFE – OUR ENVIRONMENT An enduring commitment to act to combat the Climate Change Emergency. A committed Green approach to your future that will protect our natural, urban and cultural environment. More rental housing to unblock the Housing Waiting Lists. A phased plan to regenerate the Dockyard from the old North Gate to the Southern End at Rosia. A review of the Victoria Keys Development and publication of all contractual arrangements entered into by the GSLP Government. No further development of the Queensway Quay basin. The sensitive regeneration of Rosia Bay and Little Bay for leisure use. A sustainable Town on the Eastside with zones for mixed use, residential and commercial. Get developers to deliver planning gains for the benefit of the community in exchange for developing land. An independent Public Health Study on the causes, effects and action to redress 5 environmental issues like pollution. A new North Mole Industrial Park. A new Central Town Park at the Rooke site. FAIRNESS & OPPORTUNITY A strategic approach to transport and We will make sure contracts are properly parking that is sensitive to the environment. awarded, supervised and that there is no waste of your money or abuse. BETTER SERVICES FOR YOU & YOUR A strong programme for workers and FAMILIES employees that protects and enhances workers’ rights. A radical and comprehensive Mental Health Strategy that works. -

Proceedings of the Gibraltar Parliament

PROCEEDINGSOFTHE GIBRALTARPARLIAMENT MORNING SESSION: 9.00 a.m. – 12.35 p.m. Gibraltar, Thursday, 15th March 2012 The Gibraltar Parliament 5 The Parliament met at 9.00 a.m. [MR SPEAKER: Hon. H K Budhrani QC in the Chair] 10 [CLERK TO THE PARLIAMENT: M L Farrell Esq RD in attendance] 15 Clerk: Mr Speaker. PRAYER Mr Speaker 20 Order of the Day 25 Clerk: Meeting of Parliament, Thursday, 15th March 2012. 1. Oath of allegiance. 2. Confirmation of the minutes of the last meeting of Parliament held on 15th and 16th February 2012. _________________________________________________________________ Published by © The Gibraltar Parliament, 2012 GIBRALTAR PARLIAMENT, THURSDAY, 15th MARCH 2012 Mr Speaker: May I sign the minutes as correct? (It was agreed.) Thank you. 30 Clerk: 3. Communications from the Chair. 4. Petitions. 5. Announcements. 35 Papers laid Clerk: 6. Papers to be laid: the Hon. the Chief Minister. 40 Hon. Chief Minister (Hon. F R Picardo): Mr Speaker, I have the honour to lay on the table a statement of Supplementary Estimates No. 1 of 2010/2011. Mr Speaker: Ordered to lie. 45 Clerk: The Hon. the Deputy Chief Minister. Hon. Deputy Chief Minister (Hon. Dr J J Garcia): Mr Speaker, I have the honour to lay on the table the Air Traffic Survey Report 2011. 50 Mr Speaker: Ordered to lie. Clerk: The Hon. the Minister for Sports, Culture, Heritage and Youth. Minister for Sports, Culture, Heritage and Youth (Hon. S E Linares): Mr Speaker: I have the honour 55 to lay on the table the report and audited accounts of the Gibraltar Heritage Trust for the year ended 31st March 2011 Mr Speaker: Ordered to lie. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

HM GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR PRESS OFFICE No.6 Convent Place Gibraltar Tel:20070071; Fax: 20043057 PRESS RELEASE No: 434/2012 Date: 9th July 2012 Attached is the full text of the Chief Minister’s Budget Speech at the House of Parliament on Monday 9 th July 2012. MONDAY 9 TH JULY 2012 Chief Minister’s Budget Speech 2012 Introduction Mr Speaker, this is my first budget address as Chief Minister and I have the honour to present the Government’s revenue and expenditure estimates for the year ending 31 st March 2013. Mr Speaker, this debate has traditionally also been about more than just numbers; this is a State of the Nation debate. I will therefore also report to this House on the state of the economy and public finances and on the specific budget measures and some of the projects that the Government will introduce, in pursuance of our manifesto commitments. Mr Speaker, having been in Opposition for 16 years, it is my pleasure to deliver for a Socialist Liberal Government, a budget to support working families and the disabled; a budget to support our youth and our senior citizens. A budget, Mr Speaker, to encourage business and enhance our public services. In short, Mr Speaker, this is a budget to deliver social justice and to improve the quality of life of all our citizens whilst making Gibraltar a great place to do business with the world. And that Mr Speaker, against a backdrop of continued economic turmoil in Europe. Mr Speaker no one in our community can have failed to appreciate the social problems that Europe’s economic woes are visiting upon ordinary citizens in economies more mature and diversified than our own. -

Queensland Flag -AUSTRALIA

MALTESE NEWSLETTER 43 MAY 2014 CONSULATE OF MALTA IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER MAY 2014 FRANK L SCICLUNA - LINKING MALTA AND AUSTRALIA EMAIL: [email protected] Website: www.ozmalta.page4.me Queensland flag -AUSTRALIA History of the State of Queensland flag The state flag was first introduced in 1876 when Queensland was a self-governing British colony with its own navy. In 1865, the Governor of Queensland was informed by the Admiralty in London that the colony's vessels of war should fly the Blue Ensign (British flag), with the colony's badge on the stern, and a blue pennant at the masthead. Other vessels in the colony's service were to fly the same flag, but not the pennant. At that time, Queensland did not have a badge https://www.qld.gov.au/about/how-government- works/flags-emblems-icons/state-badge/ . This prompted the submission to London of a proposed badge design. In 1875, the Governor received drawings of the badges of several colonies from London, which the Admiralty proposed to include in the Admiralty Flag Book. The Governor was asked to certify that the badge shown for the colony of Queensland was correct. The badge was composed of a representation of Queen Victoria's head, facing right, on a blue background and encircled by a white band, with the . word Queensland at the top. The Queensland Government believed it would be too difficult to adequately reproduce the head of the Queen on a flag. An alternative design, a Royal Crown superimposed on a Maltese Cross, was then submitted to London. -

MONDAY 24Th JUNE 2013 CHIEF

MONDAY 24th JUNE 2013 CHIEF MINISTER’S BUDGET ADDRESS 2013 Mr Speaker, This is my tenth budget session as a member of this Parliament and second budget address as Chief Minister and I now have the honour to present the Government’s revenue and expenditure estimates for the year ending 31st March 2014. Mr Speaker, this debate on the second reading of the Appropriation Bill has traditionally also been not just about economics, it is also a State of the Nation address touching areas beyond the numbers in the schedule to the Bill. I will nonetheless also of course report to this House on the state of the economy and public finances and on the revenue and expenditure out-turn for the previous financial year, which was the first full financial year under the Socialist Liberal Government. Mr Speaker, I will end my address to the House by outlining some of the more specific budget measures that the Government will introduce this year, in pursuance of manifesto commitments and new measures designed to address the social and business needs of the Community. Mr Speaker, this debate on the second reading will be historic in many ways. The substance of the economic points I will make will be, of course, the highlights of this debate. But one historic innovation today is the fact that the debate is being transmitted not just in audio, but also in video. Today, I believe, these proceedings are finally being broadcast on Parliament’s own website, on television by the public broadcaster and on the websites of such other national media outlets as may request it. -

Maltese Farmer Selling Goats' Milk the Chicken Hawker

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER – JANUARY 2014 ________________________________________________________________________________________ 27 CONSULATE OF MALTA IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER JANUARY 2014 FRANK L SCICLUNA - LINKING MALTA AND AUSTRALIA EMAIL: [email protected] Website: www.ozmalta.page4.me MALTESE FARMER SELLING GOATS’ MILK THE CHICKEN HAWKER From paintings of Chev. Edward Caruana Dingli (1876-1950) Chev.Edward Caruana Dingli was born in Valletta, Malta of a family of artists in 1876. In 1898, he was commissioned in the Royal Malta Artillery. He studied art under the celebrated Guze Cali (1846-1930) and at theBritish Academy in Rome, Italy. He excelled himself as a painter of Maltese landscape and folklore. Edward Caruana Dingli is the twentieth century painter many Maltese are likeliest to know by name and by fame, and some of his works have long attained iconic status. So highly regarded was he in his own lifetime that in the 1920s he was utilized by the officials responsible for the marketing of the fledgling tourist industry, and in fact the colourful images of Malta and of Maltese people he produced created what contemporary managers would call “branding” for Malta. 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER – JANUARY 2014 ________________________________________________________________________________________ WE FULLY AGREE WITH THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A MALTESE CULTURAL INSTITUE Many Maltese are now resident in foreign countries, resulting in an urgent need for the promotion of Maltese culture in these countries. It is a fact that there is the potential of Maltese communities abroad to contribute positively to Maltese culture and the do our utmost to facilitate and encourage their active participation. This is one of the aims of this e-newsletter. -

University of Birmingham the UN Committee of 24'S Dogmatic

University of Birmingham The UN Committee of 24’s dogmatic philosophy of recognition Yusuf, Hakeem; Chowdhury, Tanzil DOI: 10.2979/indjglolegstu.26.2.0437 License: Other (please specify with Rights Statement) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Yusuf, H & Chowdhury, T 2019, 'The UN Committee of 24’s dogmatic philosophy of recognition: toward a Sui Generis approach to decolonization', Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 437-460. https://doi.org/10.2979/indjglolegstu.26.2.0437 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility 04/01/2019 This was published as Yusuf, H.O. and Chowdhury, T., 2019. The UN Committee of 24's Dogmatic Philosophy of Recognition: Toward a Sui Generis Approach to Decolonization. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 26(2), pp.437-460. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or distributed in any form, by any means, electronic, mechanical, photographic, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Indiana University Press. For education reuse, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center <http://www.copyright.com/>. For all other permissions, contact IU Press at <http://iupress.indiana.edu/rights/>. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. -

Gibraltar Chronicle.Pdf

InfoGibraltar Servicio de Información de Gibraltar Aviso Las elecciones generales en Gibraltar se celebran el 17 de octubre. Como servicio a los medios españoles, se traduce la cobertura de las dos encuestas electorales realizadas por los periódicos locales: la del Gibraltar Chronicle (hoy) y la de Panorama (14 de octubre). La única fuente atribuible del presente Aviso es el periódico Gibraltar Chronicle. El artículo original está en el PDF. Gibraltar Chronicle La encuesta del Chronicle predice otra victoria aplastante del GSLP/Liberales Gibraltar, 11 de octubre de 2019 [La Alianza] GSLP/Liberales parece estar al borde de otra victoria aplastante en las elecciones generales de la próxima semana, según los resultados de una encuesta realizada para el Chronicle. El sondeo predice 10 escaños en el Parlamento para la Alianza, seis para el GSD y uno para Together Gibraltar. Excluyendo los votos en blanco y los “no sabe”, que no se cuentan en una elección, la encuesta personal a 622 votantes encontró que el 63,5% apoyaría al GSLP/Liberales, el 21,7% al GSD y el 14,1% a Together Gibraltar. Los candidatos independientes Robert Vásquez y John Charles Pons obtendrían el 0,4% y el 0,3% de los votos, respectivamente. El número de "no sabe" y votos en blanco en la encuesta general fue bajo, de sólo 2,7% y 0,46% respectivamente. Si se incluyen en el análisis global, los porcentajes se reducirían ligeramente hasta el 61,51% para el GSLP/Liberales, el 20,99% para la GSD y el 13,68% para Together Gibraltar. El sondeo, que fue realizado para la Crónica por Sonia Golt y su equipo durante un período de cuatro días a principios de esta semana, preguntó a los encuestados si votarían en bloque y, si no, cómo dividirían sus votos. -

Newsletter 280 August 2019

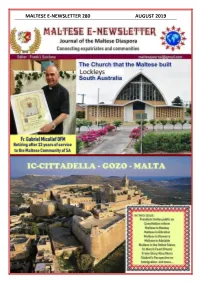

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 280 AUGUST 2019 - 2019 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 280 AUGUST 2019 Updated: President Vella launches constitutional reform public consultation exercise Jeremy Micallef President George Vella yesterday launched a public consultation exercise that will lead to the much awaited constitutional reform. The launch of a website, riformakostituzzjonali.gov.mt, will be an avenue via which recommendations and suggestions may be forwarded. The website includes links that direct the user straight to a copy of the current constitution and the process through which it will be reformed in both the English and Maltese languages. Adverts will also be shown on local media to encourage people to take part in this process. The process will not be accepting any anonymous inputs. Speaking at the press conference, President George Vella said that this must be dealt with in a holistic manner, and in a way that does not stretch on. He noted that there were "suspicions" that the two major parties will be making their own decisions on the constitutional reform, and agreed that these circumstances would never be a credible option for the people. "It must be completely open for everyone," the President insisted. The President continued by pointing out that submissions had already been made over the years, from political parties and a number of academics. This website, he said will allow everyone to have the right to express their ideas on this reform. The public will have a period of three months to send in their proposals, after which a group specially trained for this will analyse this data.