The Wes Montgomery Sound: Sonoric Individuality in Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Clippings

SAM KIRMAYER PRESS CD review and album stream, September 1st, 2017 “S’il est vrai que Sam Kirmayer ne s’éloigne pas vraiment d’un canevas bop assez bien établi, personne ne m’enlèvera le plaisir que j’ai eu à écouter Opening Statement. La musique est vibrante d’énergie et de plaisir communicatif, on sent les membres du quartette soudés et naturellement connectés.” “While it’s true that Sam Kirmayer doesn’t stray far from the well-established bop canvas, no one can take away the pleasure I had listening to Opening Statement. The music has a vibrant energy and communicative joy and the quartet feels naturally connected.” Continue reading at: http://bit.ly/2wD4TGV “35 Best Canadian Jazz Musicians Under 35”, June 22nd, 2017 “Kirmayer is probably the busiest jazz guitarist in Montreal, and one of the most in-demand sidemen, period. This is well-earned, as he is a monster musician with an incredible tone on the guitar reminiscent of greats like Wes Montgomery, George Benson and Grant Green. His sense of swing, rhythmic sophistication and melodic phrasing translate into swinging, effortless-sounding and smile-inducing jazz. Kirmayer's debut -

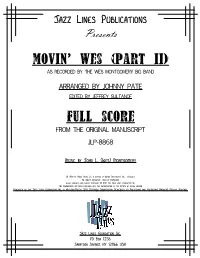

Movin Wes Part 2

Jazz Lines Publications Presents movin’ wes (part ii) as recorded by the wes montgomery big band Arranged by johnny pate edited by jeffrey sultanof full score from the original manuscript jlp-8868 Music by John L. (Wes) Montgomery © 1964 by Taggie Music Co., a division of Gopam Enterprises, Inc.. Renewed. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission. Logos, Graphics, and Layout Copyright © 2011 The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. This Arrangement Has Been Published with the Authorization of the Estate of Oliver Nelson. Published by the Jazz Lines Foundation Inc., a Not-for-Profit Jazz Research Organization Dedicated to Preserving and Promoting America's Musical Heritage. Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA wes montgomery big band series movin’ wes (part II) (1964) Background: Having solidified his stature as the most exciting and influential guitarist on the jazz scene, Wes Montgomery moved in a more commercial direction in 1963 with his recording date titled Fusion! (with string arrangements by Jimmy Jones). Wes would then be signed by Verve Records and continued to move in this direction with a big band record in 1964 titled Movin’ Wes (arrangements by Johnny Pate); Bumpin’ (string arrangements by Don Sebesky) and Goin’ Out of My Head (big band arrangements by Oliver Nelson) in 1965; and in 1966, his final two large-scale recording dates for Verve: Tequila (string arrangements by Claus Ogerman) and California Dreamin’ (string arrangements by Don Sebeksy). While many have criticized the direction that Wes moved in during what would be become his final years, there is no disputing that his playing remained consistently impressive. -

COMPLETE CATALOG with All Information

Available Pat Martino transcription books: PM #1 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: Solos 1968-1974 Bebop & Beyond: Sideman Years I (40 pages) PM #2 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: Solos 1963-1964 Swing To Bop: Sideman Years II (42 pages) PM #3 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: Solos 1964/1965 More Swing To Bop: Sideman Years III (38 pages) PM #4 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: Solos 1965 - 1967 Organ Standards: Sideman Years IV (41 pages) PM #5 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: Solos 1973-1977 In The Seventies: Sideman Years V (43 pages) PM #6 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: EL HOMBRE [1967] (34 pages) PM #7 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: STRINGS! [1967] (27 pages) PM #8 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: EAST! [1968] (35 pages) PM #9 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: FOOTPRINTS [1972] (36 pages) PM #10 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: LIVE! [1972] (29 pages) PM #11 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: CONSCIOUSNESS [1974] (38 pages) PM #12 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: WE'LL BE TOGETHER AGAIN [1976] (34 pages) PM #13 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: JOYOUS LAKE [1976] (32 pages) PM #14 € 14,95/$ 22,95 Pat Martino: THE RETURN [1987] (58 pages) PM #15 € 5,95/$ 8,95 P.M.'s solos on Bob Kenmotsu's BRONX TALE [1994] (17 pages) PM #16 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: INTERCHANGE [1994] (44 pages) PM #17 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: NIGHTWINGS [1994] (32 pages) PM #18 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: THE MAKER [1994] (32 pages) PM #19 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: STONE BLUE [1998] (36 pages) PM #20 € 9,95/$ 15,95 Pat Martino: EXIT [1976] (35 pages) PM #21 € 19,95/$30,95 Pat Martino: LIVE AT YOSHI's [2000] (70 pages) PM -

Robert Glasper's In

’s ION T T R ESSION ER CLASS S T RO Wynton Marsalis Wayne Wallace Kirk Garrison TRANSCRIP MAS P Brass School » Orbert Davis’ Mission David Hazeltine BLINDFOLD TES » » T GLASPE R JAZZ WAKE-UP CALL JAZZ WAKE-UP ROBE SLAP £3.50 £3.50 U.K. T.COM A Wes Montgomery Christian McBride Wadada Leo Smith Wadada Montgomery Wes Christian McBride DOWNBE APRIL 2012 DOWNBEAT ROBERT GLASPER // WES MONTGOMERY // WADADA LEO SmITH // OrbERT DAVIS // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2012 APRIL 2012 VOLume 79 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

20Questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker

20questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker If Benny Goodman was the “King of Swing” periodically to continue his studies over the B-Town and Edward Kennedy Ellington was “the Duke,” next decade, leading a renowned IU-based then David Baker could be called “the Dean big band while expanding his artistic and Hero and Jazz of Jazz.” Distinguished Professor of Music at compositional horizons with musical scholars Indiana University and conductor of the Smithso- such as George Russell and Gunther Schuller. nian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, he is at home In 1966 he settled in the city for good and Legend performing in concert halls, traveling around the began what is now a world-renowned jazz world, or playing in late-night jazz bars. studies program at IU’s Jacobs School of Music. Born in Indianapolis in 1931, he grew up A pioneer of jazz education, a superlative in a thriving mid-20th-century local jazz scene trombonist forced in his early 30s to switch that begat greats such as J.J. Johnson and Wes to cello, a prolific composer, Pulitzer and Montgomery. Baker first came to Bloomington Grammy nominee and Emmy winner whose as a student in the fall of 1949, returning numerous other honors include the Kennedy 56 Bloom | August/September 2007 Toddler David in Indianapolis, circa 1933. Photo courtesy of the Baker family Center for the Performing Arts “Living Jazz Legend Award,” he performs periodically in Bloomington with his wife Lida and is unstintingly generous with the precious commodity of his time. -

Identification and Analysis of Wes Montgomery's Solo Phrases Used in 'West Coast Blues'

Identification and analysis of Wes Montgomery's solo phrases used in ‘West Coast Blues ’ Joshua Hindmarsh A Thesis submitted in fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Masters of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music The University of Sydney 2016 Declaration I, Joshua Hindmarsh hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person except for the co-authored publication submitted and where acknowledged in the text. This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of a higher degree. Signed: Date: 4/4/2016 Acknowledgments I wish to extend my sincere gratitude to the following people for their support and guidance: Mr Phillip Slater, Mr Craig Scott, Prof. Anna Reid, Mr Steve Brien, and Dr Helen Mitchell. Special acknowledgement and thanks must go to Dr Lyle Croyle and Dr Clare Mariskind for their guidance and help with editing this research. I am humbled by the knowledge of such great minds and the grand ideas that have been shared with me, without which this thesis would never be possible. Abstract The thesis investigates Wes Montgomery's improvisational style, with the aim of uncovering the inner workings of Montgomery's improvisational process, specifically his sequencing and placement of musical elements on a phrase by phrase basis. The material chosen for this project is Montgomery's composition 'West Coast Blues' , a tune that employs 3/4 meter and a variety of chordal backgrounds and moving key centers, and which is historically regarded as a breakthrough recording for modern jazz guitar. -

NPR Music's 50 Favorite Albums of 2010 Recommended by NPR

Best Music Of 2010: The Complete List Use the list below to browse NPR's best music of 2010 recommendations. Each critic's list is presented separately. Click on the article names to read our critics' comments about the albums. NPR Music's 50 Favorite Albums Of 2010 Recommended by NPR Music Staff Thomas Ades, Tevot Agalloch, Marrow Of The Spirit Aloe Blacc, Good Things Khaira Arby, Timbuktu Tarab Arcade Fire, The Suburbs Erykah Badu, New Amerykah, Pt. 2: Return Of The Ankh Big Boi, Sir Lucious Leftfoot...The Son Of Chico Dusty The Black Keys, Brothers Brooklyn Rider, Dominant Curve Buke & Gass, Riposte Carolina Chocolate Drops, Genuine Negro Jig Regina Carter, Reverse Thread Chancha Via Circuito, Rio Arriba Deerhunter, Halcyon Digest Issac Delgado, Love Joyce DiDonato, Rossini: Colbran, The Muse Flying Lotus, Cosmogramma Four Tet, There Is Love In You Vittorio Grigolo, The Italian Tenor Gyptian, Hold You Hilary Hahn, Higdon & Tchaikovsky: Violin Concertos Mary Halvorson Quintet, Saturn Sings Rita Indiana, El Juidero Jamey Johnson, The Guitar Song Jonsi, Go Seu Jorge And Almaz, Seu Jorge And Almaz King Sunny Ade, Baba Mo Tunde Ray LaMontagne And The Pariah Dogs, God Willin' And The Creek Don't Rise LCD Soundsystem, This Is Happening Lower Dens, Twin Hand Movement Alexander Melnikov, Shostakovich Janelle Monae, The ArchAndroid Jason Moran, Ten Carla Morrison, Mientras Tu Dormias The National, High Violet Owen Pallett, Heartland Sondra Radvanovsky, Verdi Arias Josh Ritter, So Runs The World Away Robyn, Body Talk Kermit Ruffins, Happy Talk Christian Scott, Yesterday You Said Tomorrow Gil Scott-Heron, I'm New Here Sleigh Bells, Treats Esperanza Spalding, Chamber Music Society Mavis Staples, You Are Not Alone Sufjan Stevens, The Age Of Adz The Tallest Man On Earth, The Wild Hunt Titus Andronicus, The Monitor Sharon Van Etten, Epic Kanye West, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy Top 10 Jazz Albums Of 2010 Recommended By Patrick Jarenwattananon, A Blog Supreme 1. -

Resonance Records to Release Long Lost Wes Montgomery Tapes, Echoes of Indiana Avenue, on March 6, 2012

RESONANCE RECORDS TO RELEASE LONG LOST WES MONTGOMERY TAPES, ECHOES OF INDIANA AVENUE, ON MARCH 6, 2012 FIRST FULL ALBUM OF PREVIOUSLY UNHEARD MONTGOMERY MUSIC IN OVER 25 YEARS RELEASE COINCIDES WITH MONTGOMERY'S 88TH BIRTHDAY With a lot of sleuthing and a team of experts on the case, long lost tapes of Wes Montgomery have been discovered and restored. Resonance Records will release Echoes of Indiana Avenue - the first full album of previously unheard Montgomery music in over 25 years - on March 6, 2012, which would have been Montgomery's 88th birthday. Over a year and a half in the making, the release will provide a rare, revealing glimpse of a bona fide guitar legend. The tapes are the earliest known recordings of Montgomery as a leader, pre-dating his auspicious 1959 debut on Riverside Records. The album showcases Montgomery in performance from 1957-1958 at nightclubs in his hometown of Indianapolis, Indiana, as well as rare studio recordings. The release is also beautifully packaged, containing previously unseen photographs and insightful essays by noted music writers and musicians alike, including guitarist Pat Martino and Montgomery's brothers Buddy and Monk. On this scintillating discovery, Montgomery plays it strictly straight ahead, swinging with a momentum and ferocity that is positively visceral - a clear display of Montgomery's bebop side. Listening to these recordings only reaffirms how Montgomery exerted such a profound influence over generations of guitarists - from George Benson, Pat Martino and Joe Pass to John Scofield, Pat Metheny, Kevin Eubanks, and Russell Malone to Kurt Rosenwinkel. Joined by such Naptown colleagues as drummer Paul Parker and keyboardist Melvin Rhyne (who would later appear on Montgomery's first Riverside release), pianist Earl Van Riper, bassist Mingo Jones and drummer Sonny Johnson, as well as brothers Monk on acoustic bass and Buddy on piano (the brothers featured on one track), Montgomery swings with blistering abandon on a program of burners and ballads. -

Milt Jackson & Wes Montgomery – Bags Meets Wes (1961)

Milt Jackson & Wes Montgomery – Bags Meets Wes (1961) Written by bluesever Tuesday, 18 October 2011 18:26 - Last Updated Wednesday, 11 February 2015 15:37 Milt Jackson & Wes Montgomery – Bags Meets Wes (1961) 1. S.K.J. 2. Stablemates 3. Stairway To The Stars (take 3) play 4. Stairway To The Stars (take 2) 5. Blue Roz pl ay 6. Sam Sack 7. Jingles (take 9) 8. Jingles (take 8) 9. Delilah (take 4) 10. Delilah (take 3) Personnel: Milt Jackson (vibraphone); Wes Montgomery (guitar); Wynton Kelly (piano); Sam Jones (bass); Philly Joe Jones (drums). It’s unfair to blame Wes Montgomery for the soulless work of those who claim him as an influence; his trademark octave runs became a cash cow for the smooth jazz associated with the piped-in music of doctor’s offices and grocery stores. In reality, Montgomery was a much sought-after player by many; even Coltrane played with him for a time. Montgomery gives the impression that playing the guitar requires no less concentration than tying your shoes, fashioning a style admired (and imitated) by many. Milt Jackson, an amateur guitarist himself, reportedly leapt at the chance to play with him on this outing. Jackson seems to enjoy escaping the restrictive confines of the systematic Modern Jazz Quartet for some hard bop workouts, and the rhythm section is filled with perfect choices to achieve this goal. Nothing is taken at a tempo that would quicken the pulse, yet the metallic chime of the vibes is a perfect foil for the snap of Montgomery’s guitar. -

Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery”— Wes Montgomery (1960) Added to the National Registry: 2016 Essay by Maristella Feustle (Guest Post)*

“The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery”— Wes Montgomery (1960) Added to the National Registry: 2016 Essay by Maristella Feustle (guest post)* Album cover Original label Wes Montgomery “The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery” was the breakthrough recording that brought Wes Montgomery (1923-1968) to the attention of a wider audience and kept him there. Critically acclaimed in the year of its release, with a five-star review by Ira Gitler in “DownBeat” magazine, the album has remained a landmark recording in the history of jazz guitar, and one of timeless artistry. It is noteworthy for its creativity, its impact in securing Montgomery’s place among legendary jazz guitarists, and for its enduring inspiration to musicians and listeners. Recorded January 28 and 30, 1960 in New York City, at the storied Reeves Sound Studios, the album was one of many Riverside titles which featured Montgomery as a leader or a sideman between 1959 and 1963, and part of several Riverside sessions that included Montgomery that were made during that week. Those sessions resulted in Nat Adderley’s “Work Song” and “The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery,” both of which were produced by Orrin Keepnews. Only months earlier, Nat’s brother, Julian “Cannonball” Adderley had brought Montgomery to Keepnews’ attention after hearing him in Montgomery’s hometown of Indianapolis. While Montgomery’s debut album for Riverside and Keepnews, “The Wes Montgomery Trio” heralded “a dynamic new sound,” it was “The Incredible Jazz Guitar” with which that new sound became a permanent fixture of jazz guitar. The album itself is a study in versatility, as Montgomery excels equally on up-tempo tunes, blues, ballads, jazz waltz, and medium swing, with the support of Tommy Flanagan on piano, Percy Heath on bass, and Albert Heath on drums. -

Ted Greene's Insight About Wes Montgomery

(Some of) T ed Greene’s Insight about Wes Montgomery Physical Technique ● In regards to his left hand, Wes Montgomery never played with a pinky with single-note solos (if not extremely rare). With octave runs Wes fingered it with every other finger (1 and 3 or 2 and 4) because his hands were big enough to cover it.1 ○ His hands were pretty big. His hands could work around/cover 5 frets. ● Wes’ right hand was more a strum like sound. He would not simply go across the strings but go down and across aiming more into the sound board. It’s rounder with a bigger sound.2 ○ His thumb on single notes had a ‘flapping’ sound when struck harder. It gives a different kind of pop. ○ There is a difference in horizontal and more angled inward thumb picking. When you press more inward and then release (with an arched hand (angled angled down wrist)) you get a new kind of attack. It’s fuller in sound (hence why Wes played that way). ○ You do not want to do octaves with two fingers. It may be clearer in pitch, but it loses that percussive sound. Ted described it as a “little drum sound.”3 ○ Wes could pick fast with his thumb. He could do down and upstrokes. One way to relieve that strain of overdoing it (especially on up tempo tunes) was slurring. ○ Some of Wes’ fast chord lines he was known for only used really fast downstrokes. ○ “I’m not 100% convinced, but I tend to think (with octave playing) he’s watching the lowest note because his brother’s bass thing. -

Jazz Guitar: the History, the Players

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 4-2002 Jazz Guitar: The History, The Players James Aubrey Crawford University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Crawford, James Aubrey, "Jazz Guitar: The History, The Players" (2002). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/528 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM .I 'J SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL Name: __~.)~'~~~~C:~~~4~~~~~~~~~---------- ____________________________ __ College: &b + SciCNtc..c..-S Faculty Mentor: -Pcp.y..\ U.4!C I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project com . ors level undergraduate research in this field. Signed: , Faculty Mentor Date: 4 W/ 0:2 Comments (Optional): Jazz Guitar: The History, The Players Jim Crawford Paul Haar, Faculty Mentor, UT Jazz Faculty Thomas Broadhead, Director, University Honors Thanks to Paul Haar of the UT Jazz Facultyfor his help, guidance, and his ability to manufacture time from thin air in order to meet with me. Thanks also goes to Konrad Whitt for allowing me to burn CDs at his expense, and steal his stereo for my presentations.