Tecumseh's Confederacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincoln AL Star Food Mart #110 1315 Hyw 269 Jaspe

Name Location City State Citgo Lincoln Super Mart 1-20 Exit 168 (76022 Hwy 77) Lincoln AL Star Food Mart #110 1315 Hyw 269 Jasper AL Lakeside Oil Hwy 1 / 431 & Cecil Dr (3281 S Eufaula Ave) Eufaula AL Citgo Food Store # 109 Hwy 1 / Hwy 431 & Hwy 27 Abbeville AL Hobo Pantry #24 Hwy 10 / 53 / 231 & 438 SA Graham Blvd Brundidge AL Brundidge Amoco Hwy 10 / 53 / 231 N Brundidge AL Big Little Store #612 Hwy 12 / 55 / 84 (11183 Hwy 84) Andalusia AL Sun Valley Market Hwy 12 / 84 & Elmer Rd (9416 Hwy 84 E) Ashford AL Big Little Sunstop #619 Hwy 12 / 84 / 92 / 134 & CR 1 (3724 Hwy 84 W) Daleville AL Oc's Quick Stop (Citgo) Hwy 13 / 43 & Wayne Davis Rd (20270 Hwy 43) Mount Vernon AL Jones Truck Stop Hwy 14 (1627 West Highland) Selma AL Moulton Cowboys Hwy 157 & Coffee Rd (11327 Highway 157) Moulton AL Mac's Minit Mart Vernon Hwy 17 (44390 Hwy 17) Vernon AL Lovett Chevron Hwy 195 & Hwy 278 (14908 Hwy 278) Double Springs AL Fackler Texaco Truckstop Hwy 2 / 72 & Hwy 42 (13750 CR 42) Fackler AL Uncle Joe's Sprint Mart #40 Hwy 2 / 72 & Hwy 53 (21731 Hwy 72 W) Tuscumbia AL Quick Stop Market #107 Hwy 2 / 72 & Veterans Blvd (1021 Hwy 72 E) Tuscumbia AL Arnold's Truck Stop Hwy 20 & Hwy 43 (1460 Hwy 20) Tuscumbia AL Texaco Fuel Stop #9 Hwy 20 / 157 & Hwy 77 Muscle Shoals AL Sibley Food and Fuel Hwy 20 / 72 & 13241 HWY 150 Courtland AL Quick Mart Travel Center #18 Hwy 20 / 72 & Vine St (2125 Hwy 20 / 72) Tuscumbia AL Kangaroo Express #1577 Hwy 21 & Hwy 84 (20 Hwy 21 S) Monroeville AL Flying J Travel Plaza #603 Hwy 210 / 231 & S Oats St (2190 Ross Clark Cir) -

Creating a Frontier War: Harrison, Prophetstown, and the War of 1812. Patrick Bottiger, Ph.D., [email protected] Most Scholars

1 Creating a Frontier War: Harrison, Prophetstown, and the War of 1812. Patrick Bottiger, Ph.D., [email protected] Most scholars would agree that the frontier was a violent place. But only recently have academics begun to examine the extent to which frontier settlers used violence as a way to empower themselves and to protect their interests. Moreover, when historians do talk about violence, they typically frame it as the by-product of American nationalism and expansion. For them, violence is the logical result of the American nation state’s dispossessing American Indians of their lands. Perhaps one of the most striking representations of the violent transition from frontier to nation state is that of Indiana Territory’s contested spaces. While many scholars see this violence as the logical conclusion to Anglo-American expansionist aims, I argue that marginalized French, Miamis, and even American communities created a frontier atmosphere conducive to violence (such as that at the Battle of Tippecanoe) as a means to empower their own agendas. Harrison found himself backed into a corner created by the self-serving interests of Miami, French, and American factions, but also Harrison own efforts to save his job. The question today is not if Harrison took command, but why he did so. The arrival of the Shawnee Prophet and his band of nativists forced the French and Miamis to take overt action against Prophetstown. Furious that the Shawnee Prophet established his community in the heart of Miami territory, the French and Miamis quickly identified the Prophet as a threat to regional stability. -

The General William Henry Harrison Trail Through Portions of Vermillion County and Warren County in Indiana Modified July 7, 2019 by Curtis L

The General William Henry Harrison Trail through Portions of Vermillion County and Warren County in Indiana Modified July 7, 2019 by Curtis L. Older The Battle of Tippecanoe – November 7, 1811 Warren County Reflections, a Journal magazine published by the Warren County (Indiana) Historical Society, indicates on page one, “Where Harrison entered Warren County 1 1/2 miles southeast of State Line, a large delegation of citizens met the pilgrimage and accompanied them through the county.”1 The Warren County Reflections article contains the following on page two as follows: Harrison proceeded to the west bank, entering Warren County in the southwestern part of Mound Township on the land now owned by F.A. Lynch, in Section 32. Thence he proceeded in a northeasterly direction passing a mile east of State Line City, through the dooryard of G. H. Lucas’ home. The army camped in a small grove and here two men died and were buried and the place is now called the Gopher Hill Cemetery. This is an old Indian trail that can be traced some ten or twelve miles and is sometimes fifteen or eighteen feet wide and a foot deep. It seems reasonable to believe Harrison's Army stayed about two or three miles west of the Wabash River as they continued their march north from present day Cayuga. This was done to avoid trees growing along the area adjacent to the river and to avoid detection from Indians who may have been watching for boats on the Wabash River or for individuals following along the banks of the river. -

The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative Written by Shirley E

THE EMIGRANT MÉTIS OF KANSAS: RETHINKING THE PIONEER NARRATIVE by SHIRLEY E. KASPER B.A., Marshall University, 1971 M.S., University of Kansas, 1984 M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1998 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2012 This dissertation entitled: The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative written by Shirley E. Kasper has been approved for the Department of History _______________________________________ Dr. Ralph Mann _______________________________________ Dr. Virginia DeJohn Anderson Date: April 13, 2012 The final copy of this dissertation has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii ABSTRACT Kasper, Shirley E. (Ph.D., History) The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Ralph Mann Under the U.S. government’s nineteenth century Indian removal policies, more than ten thousand Eastern Indians, mostly Algonquians from the Great Lakes region, relocated in the 1830s and 1840s beyond the western border of Missouri to what today is the state of Kansas. With them went a number of mixed-race people – the métis, who were born of the fur trade and the interracial unions that it spawned. This dissertation focuses on métis among one emigrant group, the Potawatomi, who removed to a reservation in Kansas that sat directly in the path of the great overland migration to Oregon and California. -

Peace of Mind Solutions for Life

October 2016 FREE Northwest Edition Reaching Seniors Throughout Lake And Porter Counties 26,500 Circulation Spotlight 4 Faith 15 In God We TrustTrust www.seniorlifenewspapers.comwww.seniorlifenewspapers.com SERVINGERVING ADULTSDULTS 50 YEARSEARS AND BETTER. Vol. 21, No. 12 MEMBERS — Joel and Lee Ebert of Crown AUTO CLUB Point stand in front of their 1941 Chevy outside Suzy’s Diner in Hebron during a recent car show and fundraiser for the Wi- namac Old Auto Club. — Kent Widener of Hobart sits BEHIND THE WHEEL behind the wheel of his white-over-seafood-green 1954 Chevy Bel Air with hish wife, Kathy, beside him. Text and Photos Photos had events eventss atat churches and for church models,d l andd vehicle hi l styles t l when h one clublb hash otherth indoor i d events, t liklike a By CARRIE STEINWEG food banks and Alzheimer’s research. goes to one of the shows or events. February valentine’s event. Pettit Feature Writer “We’re a very giving club,” he said. “We have everything from a 1908 said the club is always looking for Sometimes at the events, they accept Buick to 1970s Dodges — just any- members and invites those interested Indiana’s first car club was founded freewill donations and sometimes it’s thing classic. We have a lot of cars in to visit the website, winamacoldauto- in 1950, and it’s still going strong generous donations from members the club. One was a lead car in the club.weebly.com, where one will find with about 141 members and about that help support charitable groups. -

Pioneer Founders of Indiana 2014

The Society of Indiana Pioneers "To Honor the Memory and the Work of the Pioneers of Indiana" Pioneer Founders of Indiana 2014 The Society of Indiana Pioneers is seeking to identify Indiana Pioneers to recognize and honor their efforts in building early Indiana foundations. Each year, 15-20 counties are to be selected for honoring pioneers at each annual meeting. The task of covering all 92 counties will be completed by 2016, the year we celebrate the centennial of the founding of the Society of Indiana Pioneers. For 2014, the Indiana counties include the following: Adams, Decatur, Fountain, Grant, Jasper, Jay, Jennings, LaGrange, Marion Martin, Owen, Pulaski, Ripley, Spencer, Steuben, Vermillion, Wabash, Warrick Office: 140 North Senate Avenue, Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2207 (317) 233-6588 www.indianapioneers.org [email protected] The Pioneer Founders of Indiana Program 2014 “To honor the memory and the work of the pioneers of Indiana” has been the purpose and motto of The Society of Indiana Pioneers from the very beginning. In fact, these words compose the second article of our Articles of Association. We carry out this mission of the Society in three distinct ways: 1.) we maintain a rich Pioneer Ancestor Database of proven ancestors of members across one hundred years; 2.) Spring and Fall Hoosier Heritage Pilgrimages to significant historic and cultural sites across Indiana; and 3.) educational initiatives, led by graduate fellowships in pioneer Indiana history at the master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation levels. To commemorate the Society’s centennial and the state’s bicentennial in 2016, the Society is doing something new and dipping its toes in the world of publishing. -

The Indians and the Michigan Road

The Indians and the Michigan Road Juanita Hunter* The United States Confederation Congress adopted on May 20, 1785, an ordinance that established the method by which the fed- eral government would transfer its vast, newly acquired national domain to private ownership. According to the Land Ordinance of 1785 the first step in this transferral process was purchase by the government of all Indian claims. In the state of Indiana by 1821 a series of treaties had cleared Indian title from most land south of the Wabash River. Territory north of the river remained in the hands of the Miami and Potawatomi tribes, who retained posses- sion of at least portions of the area until their removals from the state during the late 1830s and early 1840s.’ After a brief hiatus following 1821, attempts to secure addi- tional cessions of land from the Indians in Indiana resumed in 1826. In the fall of that year three commissioners of the United States government-General John Tipton, Indian agent at Fort Wayne; Lewis Cass, governor of Michigan Territory; and James Brown Ray, governor of Indiana-met with leading chiefs and warriors of the Potawatomi and Miami tribes authorized in part “to propose an exchange of land. acre for acre West, of the Mississippi . .’’z The final treaty, signed October 26, 1826, contained no provision for complete Indian removal from the state. The Potawatomis agreed, however, to three important land cessions and received cer- tain benefits that included payment of debts and claims held against * Juanita Hunter is a graduate of Indiana State Teachers College, Terre Haute, and was a social studies teacher at Logansport High School, Logansport, Indiana, at the time of her retirement. -

Peace, Power and Persistence: Presidents, Indians, and Protestant Missions in the American Midwest 1790-1860

PEACE, POWER AND PERSISTENCE: PRESIDENTS, INDIANS, AND PROTESTANT MISSIONS IN THE AMERICAN MIDWEST 1790-1860 By Rebecca Lynn Nutt A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History—Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT PEACE, POWER AND PERSISTENCE: PRESIDENTS, INDIANS, AND PROTESTANT MISSIONS IN THE AMERICAN MIDWEST 1790-1860 By Rebecca Lynn Nutt This dissertation explores the relationships between the Shawnee and Wyandot peoples in the Ohio River Valley and the Quaker and Methodist missionaries with whom they worked. Both of these Indian communities persisted in the Ohio Valley, in part, by the selective adoption of particular Euro-American farming techniques and educational methods as a means of keeping peace and remaining on their Ohio lands. The early years of Ohio statehood reveal a vibrant, active multi-cultural environment characterized by mutual exchange between these Indian nations, American missionaries, and Euro- and African-American settlers in the frontier-like environment of west-central Ohio. In particular, the relationships between the Wyandot and the Shawnee and their missionary friends continued from their time in the Ohio Valley through their removal to Indian Territory in Kansas in 1833 and 1843. While the relationships continued in the West, the missions themselves took on a different dynamic. The teaching methods became stricter, the instruction observed religious teaching more intensely, and the students primarily boarded at the school. The missionary schools began to more closely resemble the notorious government boarding schools of the late-nineteenth century as the missions became more and more entwined with the federal government. -

HPSA Geographic Area: East Baton Rouge LSU Gardere Area Facility: Baton Rouge Primary Care Collaborative, Inc

PRIMARY CARE: Alabama County and County Equivalent Listing Autauga County Geographic Area: Autaugaville Population Group: Low Income - Montgomery/Prattville Baldwin County Population Group: Low Income - South Baldwin Barbour County Geographic Area: Barbour County Facility: Easterling Correctional Facility Facility: Ventress Correctional Facility Bibb County Geographic Area: Bibb County Facility: Bibb Correctional Facility Facility: BIBB MEDICAL ASSOCIATES Facility: Cahaba Medical Care Foundation Blount County Geographic Area: Blount County Bullock County Geographic Area: Bullock County Facility: Bullock Correctional Facility Facility: EPEDIATRICS AND FAMILY CARE CLINIC Butler County Geographic Area: Butler County Calhoun County Population Group: LI - Calhoun County Chambers County Geographic Area: La Fayette Population Group: Low Income - Valley Cherokee County Geographic Area: Cherokee County Chilton County Geographic Area: Chilton County Choctaw County Geographic Area: Choctaw County Clarke County Geographic Area: Clarke County Facility: GROVE HILL HEALTH CARE Clay County Geographic Area: Clay County Cleburne County Geographic Area: Cleburne County Colbert County Population Group: Low Income - Colbert/Lauderdale Counties Conecuh County Geographic Area: Conecuh County Coosa County Geographic Area: Coosa County Covington County Population Group: LI - Covington County Crenshaw County Geographic Area: Crenshaw County Cullman County Population Group: Low Income - Cullman County Dale County Geographic Area: Dale County Dallas County Geographic Area: Dallas County Facility: Rural Health Medical Program, Inc. DeKalb County Geographic Area: Dekalb County Facility: FORT PAYNE PEDIATRICS - WATERWORKS Elmore County Geographic Area: Tallassee Service Area Population Group: Low Income - Montgomery/Prattville Facility: CF-Draper Correctional Facility Facility: Julia Tutwiler Prison for Women Facility: Staton Correctional Facility Facility: WETUMPKA FAMILY RURAL HEALTH CLINIC Escambia County Geographic Area: Escambia County Facility: Buford L. -

General Picture Collection Ca. 1860S–1980S

Collection # P 0411 GENERAL PICTURE COLLECTION CA. 1860S–1980S Collection Information 1 Scope and Content Note 3 Series Contents 5 Cataloging Information 75 Processed by Barbara Quigley and Barbara Zimmer 17 November 2004 Revised: 24 January 2005, 16 March 2005, 13 April 2011, 29 April 2015, 18 March 2016, 9 May 2018 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 25 boxes COLLECTION: COLLECTION Ca. 1860s–1980s DATES: PROVENANCE: Multiple RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 0000.0395, 0000.0396, 0000.0401, 0000.0414, 1932.0201, 1932.0301, NUMBER: 1935.0502, 1935.1105, 1936.0203, 1936.0712, 1937.0608, 1937.0804, 1937.0903, 1938.0244, 1938.0617, 1938.0703, 1938.0803, 1938.0804, 1939.0805, 1941.1008, 1943.0603, 1946.0012, 1946.0412, 1946.0702, 1946.0802, 1946.1216, 1947.0907, 1947.1101, 1947.1106, 1948.0318, 1948.1111, 1949.0522, 1949.0805, 1950.0002, 1950.0514, 1950.0606, 1952.1122, 1953.0015, 1953.0016, 1953.0205, 1953.0221, 1953.0526, 1954.0005, 1954.0414, 1955.0509, 1955.0906, 1955.0907, 1956.0418, 1956.1204, 1957.0029, 1957.0212, 1957.1111, 1960.0005, 1961.0309, 1961.0702, 1962.0028, 1962.0029, 1962.1212, 1962.1213, 1963.0012, 1963.0031, 1963.0047, 1963.0064, 1963.0606, 1964.0064, 1964.0108, 1964.0213, -

Turner's the Frontier in American History Is Considered by Many

HOW AMERICA REMEMBERS: ANALYSIS OF THE ACADEMIC INTERPRETATION AND PUBLIC MEMORY OF THE BATTLE OF TIPPECANOE Brent S. Abercrombie Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University December 2011 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________________ Philip V. Scarpino, Ph. D., Chair ___________________________ Modupe Labode, Ph. D. Master’s Thesis Committee ___________________________ Marianne S. Wokeck, Ph. D. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank for several people their efforts throughout my thesis process. The first individual I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Philip Scarpino, for his insight, encouragement, and patience in helping me construct my thesis from its very rough origins. I would also like to thank the members of my thesis committee, Dr. Modupe Labode and Dr. Marianne Wokeck, for agreeing to work with me and helping make my thesis clearer and more comprehensive. I would also like to express appreciation to the library staffs at the Indiana State Library, Indiana Historical Society, Lilly Library at Indiana University, and the William Clements Library at the University of Michigan for their help with my research. I would also like to extend a special thank you to Marcia Caudell, whose ability to ask critical questions forced me to strengthen and refine my argument. I am also deeply indebted to her for her help with editing and being my sounding board. I would also like to thank my family and friends for their continued support and words of encouragement. -

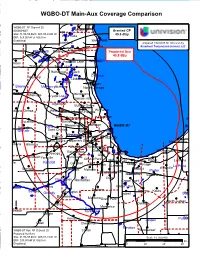

WGBO CP-Aux Comparison.Pdf

Menomonee Falls Sussex Oconomowoc Whitefish Bay e Lake Mills Delafield Jefferson WGBO-DT Main-Aux Coverage Comparison Jefferson DousmanWaukeshaWaukesha Milwaukee Milwaukee Greenfield Fort Atkinson North Prairie WGBO-DT RF Channel 35 Franklin 0000034007 Palmyra Mukwonago Granted CP erton Site:Whitewater 41-53-55.98 N 087-37-23.01 W 40.8 dBµ ERP: 615.00 kW at 418.0 m Wind Lake MiltonDirectional East Troy WindRacine Point Waterford prepared 1/30/2018 for Univision by Racine Broadcast Transmission Services, LLC nesville WalworthElkhorn Burlington Union Grove Proposed Aux Delavan 40.8 dBµ Lake Geneva KenoshaKenosha Clinton Paddock Lake Walworth Twin Lakes Beloit Richmond Antioch kton ZionLake Roscoe Harvard Lindenhurst Johnsburg sney Park Waukegan Boone McHenryMcHenry North Chicago ord Belvidere Mundelein Marengo Crystal Lake Vernon Hills Lake M Algonquin Buffalo Grove Benton Winnetka Kirkland Genoa West Dundee Arlington Heights Elgin Evanston Schaumburg Stevensvi Sycamore Bartlett Bloomingdale Norridge WGBO-DT BerrienBridgman elle De Kalb Kane DeKalb Saint Charles Elmhurst Cook WheatonDuPage Batavia WestchesterChicago B North Aurora Downers Grove New Buffalo Shabbona Hinckley Aurora Woodridge Bridgeview Bolingbrook Oak Lawn Michigan City New Carl Oswego Alsip Whiting SandwichYorkville Romeoville Orland Park Calumet City Porter La Porte Earlville Kendall Lockport Gary Tinley Park Lansing Portage La Porte a Westville North Sheridan Joliet Mokena Hobart Chicago Heights Porter MerrillvilleLake Valparaiso Walker Will Crete Channahon Manhattan