Sexuality Education in Sweden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adressat Göteborg XX Januari 1995

Utbildningsgruppen Göteborg 17 juni 2010 Helene Odenjung (fp), Göteborg, ordförande Marie Lindén (v), Göteborg, vice ordförande Ann Lundgren (s), Göteborg Kristina Tharing (m), Göteborg Peter Ohlsson (s), Ale Jan Österdahl (m), Kungsbacka Pär Göran Björkman (s), Alingsås Camilla Waltersson Grönvall (m), Lilla Edet Ing-Marie Samuelsson (s), Härryda Staffan Gustavsson (mp), Lerum Anne-Lie Sundling (kd), Öckerö Carola Granell (s), Stenungsund Anders Holmensköld (m), Kungälv Torsten Gustafsson (s), Tjörn Kent Vahlén (fp), Partille Claes Olsson (m), Mölndal Kallelse till sammanträde i Utbildningsgruppen Tid: Torsdag 24 juni 2010, kl 09.00-12.00 Plats: GR-Huset, Rum 255 (samt 253) Samling kl 08.30-09.00 med morgonkaffe. Sammanträdet äger rum enligt följande arbetsordning 09.00-11.00 Föredragningar 11.00-11.30 Gruppmöten 11.30-12.00 Sammanträde Förslag till ärendelista: Föredragningar Margrethe Kristensson finns tillgänglig kl i början av sammanträdet för att svara på frågor kring förskoleavtalet. 09.00-10.00 Definitivintagning till gymnasieskolan 2010 (Susanne Carlström) 10.00-10.15 Paus 10.15-10.30 Regional sfi (Sten Janson) 10.30-11.00 Regional samverkan för kvalitet och utveckling (Peter Holmström, Margaretha Allen) Beslutsärenden 1. Val av protokollsjusterare 2. Definitivintagning till gymnasieskolan 2010 (Handling bifogas) 3. Direktiv för gymnasieintagningen inför 2011 (Handling bifogas) 4. Tidpunkter för Utbildningsgruppens junisammanträden 2011 och kommande mandatperiod (Handling bifogas) 5. Betr särskilda varianter (Handling bifogas) -

Bedömningsh Andboken

Bedömningshandboken förantagningtillhögskoleutBildning2013–2014 Produktion Universitets- och högskolerådet, UHR Layout & Original Birgitta Klingsäter Foto Olle Melkerhed BedömningshandBoken 2013/2014 Under våren 2013 kommer den digitala bedömningshandboken att presenteras. Någon tryckt upplaga för 2013 kommer alltså inte utan detta något uppdaterade pdf-dokument finns tillgänglig tills vidare. Målgruppen för bedömningshand- böcker är i första hand personal vid landets högskolor och universitet i sitt arbete med antagning och studievägledning. Vår strävan är att göra innehållet lättläst. Under arbetsåret kan du följa vårt kontinuerliga arbete genom protokollen från bedömningshandboksgruppens mö- ten, vilka du hittar på UHRs webbplats, www.uhr.se för NyA användare, bedömningshandböcker. Där hittar du också den e-postadress, till vilken synpunkter och frågor på innehållet i handböcker kan sändas. Bedömningshandboken är framtagen och bearbetad av en arbetsgrupp utsedd av Sveriges universitets- och högskoleförbund, SUHF, och den utgör, vid sidan om högskoleförordning och Högskoleverkets föreskrifter, underlaget för antagning till utbildning på grundnivå och avancerad nivå. Samma arbetsgrupp har uppdraget att ta fram bedömningshandböcker för utländsk förutbildning på gymnasial nivå samt för grundläggande behörighet för program på avancerad nivå liksom riktlinjer för verifiering av meriter för kurser och program på avancerad nivå. Dessa två senare delar av bedömningshandböcker nås via UHRs webbplats, www.uhr.se. Vi som arbetar med de tre -

Clarence Wret –

B [email protected] Í www.pas.rochester.edu/~cwret Clarence Wret clarenc3 Employment 07/16/2018 —. Today Postdoctoral Researcher, Robert Marshak fellow, University of Rochester, Based at FNAL, working on T2K, DUNE and MINERvA. T2K I convene the main T2K oscillation analysis and the near-detector constraints group. As such, I co-supervise about 7 Ph.D. students. Aside from convening, I have continued to develop the interaction model and oscillation analysis at T2K and remain an active developer and manager of key T2K analysis software. I primarily work on the joint near and far detector oscillation framework, developing the near-detector selections, the NEUT neutrino interaction generator, the T2KReWeight systematics package, and the neutrino interaction comparison tool NUISANCE. DUNE Lending from my T2K experience, I was a central player in developing and implementing the DUNE interaction model, used in the DUNE long baseline analysis for the DUNE Technical Design Report. I also advised and discussed with the DUNE LBL analysers on methods and statistical techniques used on T2K. I am heavily involved in the prototype for the DUNE near-detector, in which we are recycling MINERvA as a rock muon tagger, tracker and calorimeter for the proposed ArgonCube 2x2 demonstrator. I am supervising the reassembling of MINERvA and am responsible for modifying and integrating the updated MINERvA DAQ into the demonstrator system. T2K-NOvA Being a T2K collaborator at FNAL has opened doors for the future T2K-NOvA joint analysis, of which I have been partaking in since its conception. I have significantly contributed to unifying the interaction model and statistical framework. -

Slutantagningen 2019

Slutantagningen 2019 Slutantagningen 2019 Antagningspoäng och betygsmedelvärde • Kommunvis med skolor i bokstavsordning • Kommunvis med utbildningar i bokstavsordning I följande dokument kan du se den slutliga antagningspoängen för kommunala och fristående gymnasieskolor i Göteborgsregionen. För att lättare hitta i dokumentet kan du välja att visa Bokmärken, då ser du kommunerna uppdelade per skola och därefter kommunerna uppdelade per utbildning. De kommuner som ingår i Göteborgsregionen är: Ale, Alingsås, Göteborg, Härryda, Kungsbacka, Kungälv, Lerum, Lilla Edet, Mölndal, Partille, Stenungsund, Tjörn och Öckerö. Förklaring: Antagningspoäng (slut) = Slutlig antagningspoäng, vilket motsvarar den sist antagna elevens betyg. Vid ansökan till program med färdighetsprov ingår även provresultatet i denna summa, d v s summan av den sist antagna elevens slutbetyg och eventuella provresultat. Medelvärde (slut) = Utbildningens medelvärde, vilket motsvarar medelvärdet av de antagna elevernas slutbetyg. 1 = Alla behöriga sökande är antagna. 2 = Enbart test. Utbildningen har inte antagning på betyg utan enbart på test. 3 = Ingen antagen på poäng. 4= Till introduktionsprogram görs ingen preliminärantagning. 5 = Placering sker manuellt, ingen antagningspoäng. Slutantagningen 2019 2019-06-19 - Antagningsår 2019 Antagningspoäng Kommun: Ale Antagningspoäng Medelvärde Antagningspoäng Medelvärde Antagningspoäng Medelvärde Utbildning (prel) (prel) (slut) (slut) (reserv) (reserv) Ale gymnasium,Introduktionsprogram IM - Individuellt alternativ 4) 5) Ale gymnasium,Introduktionsprogram -

Institution Code Institution Title a and a Co, Nepal

Institution code Institution title 49957 A and A Co, Nepal 37428 A C E R, Manchester 48313 A C Wales Athens, Greece 12126 A M R T C ‐ Vi Form, London Se5 75186 A P V Baker, Peterborough 16538 A School Without Walls, Kensington 75106 A T S Community Employment, Kent 68404 A2z Management Ltd, Salford 48524 Aalborg University 45313 Aalen University of Applied Science 48604 Aalesund College, Norway 15144 Abacus College, Oxford 16106 Abacus Tutors, Brent 89618 Abbey C B S, Eire 14099 Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar Sc 16664 Abbey College, Cambridge 11214 Abbey College, Cambridgeshire 16307 Abbey College, Manchester 11733 Abbey College, Westminster 15779 Abbey College, Worcestershire 89420 Abbey Community College, Eire 89146 Abbey Community College, Ferrybank 89213 Abbey Community College, Rep 10291 Abbey Gate College, Cheshire 13487 Abbey Grange C of E High School Hum 13324 Abbey High School, Worcestershire 16288 Abbey School, Kent 10062 Abbey School, Reading 16425 Abbey Tutorial College, Birmingham 89357 Abbey Vocational School, Eire 12017 Abbey Wood School, Greenwich 13586 Abbeydale Grange School 16540 Abbeyfield School, Chippenham 26348 Abbeylands School, Surrey 12674 Abbot Beyne School, Burton 12694 Abbots Bromley School For Girls, St 25961 Abbot's Hill School, Hertfordshire 12243 Abbotsfield & Swakeleys Sixth Form, 12280 Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge 12732 Abbotsholme School, Staffordshire 10690 Abbs Cross School, Essex 89864 Abc Tuition Centre, Eire 37183 Abercynon Community Educ Centre, Wa 11716 Aberdare Boys School, Rhondda Cynon 10756 Aberdare College of Fe, Rhondda Cyn 10757 Aberdare Girls Comp School, Rhondda 79089 Aberdare Opportunity Shop, Wales 13655 Aberdeen College, Aberdeen 13656 Aberdeen Grammar School, Aberdeen Institution code Institution title 16291 Aberdeen Technical College, Aberdee 79931 Aberdeen Training Centre, Scotland 36576 Abergavenny Careers 26444 Abersychan Comprehensive School, To 26447 Abertillery Comprehensive School, B 95244 Aberystwyth Coll of F. -

Beviljade Atlas Partnerskap 2019 (Pdf)

Atlas partnerskap 2019, dnr. 3.3.1.42-00160-2019 Diarienummer Organisation Län Samarbetsland Partnerorganisation Beviljat antal Bifallet bidrag 3.3.1.42.11239-2019 Duveholms gymnasiesärskola Södermanlands län Kina Yunnan Vocational College of Special Education 30 334 375 3.3.1.42.11240-2019 Nösnäsgymnasiet Västra Götalands län Bosnien-Hercegovina Prva gimnazija 26 114 945 3.3.1.42.11241-2019 De Geergymnasiet Östergötlands län Sydafrika Kliptown Youth Program 24 224 200 3.3.1.42.11242-2019 Ulriksdalsskolan Stockholms län Kina The Affiliated High School of UIBE (Beijing No 94 High School) 48 202 875 3.3.1.42.11251-2019 YBC Stockholms län Uganda Sunrise preparatory school 35 236 888 3.3.1.42.11254-2019 IHGR, Utbildningsförvaltningen Göteborgs kommun Västra Götalands län Uganda High Standard secondary school 12 103 000 3.3.1.42.11257-2019 Klinnekärr Förskola Hallands län Tanzania SOS Children´s Villages Association Zanzibar 6 44 490 3.3.1.42.11265-2019 Helsjöns folkhögskola Västra Götalands län Japan The YMCA Kobe, Japan 15 125 500 3.3.1.42.11272-2019 Fischerströmska gymnasiet Karlskrona Blekinge län Indien Little Lambs School 16 133 500 3.3.1.42.11276-2019 Birger Sjöberggymnasiet Västra Götalands län Bosnien-Hercegovina JU Gimnazija Mustafa Novalic 30 146 250 3.3.1.42.11278-2019 TF Sandbergska Stockholms län Argentina National School of Monserrat 17 148 500 3.3.1.42.11286-2019 Olympiaskolan Skåne län Uganda Kisoro Vision Secondary School 24 159 994 3.3.1.42.12293-2019 Roslagsskolan Stockholms län Indien St John School 20 232 280 3.3.1.42.12295-2019 -

Berättelser Som Förändrar Utvärdering Och Didaktisk Diskussion Kring Ett Nationellt Läsprojekt För Ungdomar

Nr 35 Berättelser som förändrar Utvärdering och didaktisk diskussion kring ett nationellt läsprojekt för ungdomar Olle Nordberg 2019 Abstract Olle Nordberg: Berättelser som förändrar. Utvärdering och didaktisk diskussion kring ett nationellt läsprojekt för ungdomar. Svenska i utveckling nr 35. Uppsala universitet, Uppsala. Narratives that change. Evaluation and pedagogical discussion on a national literary reading project for young people. During 2017, a comprehensive national project concentrating on literary reading was performed in secondary and upper secondary schools all over Sweden. Around 30,000 teenagers were involved, reading novels as whole classes with the literary discussion in the centre. This report is an evaluation of that project, made with the participant experiences in focus, and from a literary teaching point of view. The project was initiated and designed by the foundation Läsrörelsen. The aim of the project was to highlight the discussion around the content of books, bookclub-style, not fixating on technical details, grades and tests, biographical details or similar. Accordingly, ten novels with rather “strong” or even poignant content were part of the project. Each school or teacher then made their own choice among the titles available. The rich evaluation material submitted by the participating pupils, teachers, librarians and principals clearly shows that the project really had numerous beneficial effects. This was seen most of all among young readers who expressed the meaning by discussing, disagreeing, engaging, empathising, reflecting and making references to the world around them, all based on the current novel. From a literary pedagogical perspective, the outcome of the project points out several opportunities for teaching literature in schools of today. -

Erasmus+ Contact Seminar on Vocational Education and Training

Erasmus+ Contact Seminar on Vocational Education and Training WORKBASED LEARNING IN VET Reykjavík, Iceland 14 – 16 January 2015 SEMINAR COMPENDIUM; Information on participants and project ideas 14 January 2015 Belgium Virginia Dafos Rodrigo Institution and position: Ministère de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles - Centre de Coordination et de gestion des programmes européens Chargée de Mission programme Ersamus+ Type of institution: Public authority Web site: www.enseignement.be Email address: [email protected] Project idea: To Establish relationships with transnational partners in connection with the Programm Ersamus+ ( K1). Sectors: - Wood - Electronics - Animal care - Sale - Technicians of office(desk) - Mechanics of garage - Electricity Description of The CCG PE-CGEO for secondary vocational education, secondary alternately education organisation: and training, and secondary education for specific needs, was set up by the decree of the French speaking Community of the 1/02/2008. It is chaired by a representative of the Minister of compulsory Education. The CCG is a service of the Ministry of Education. The CCG is an intermediate between the schools organizing a vocational education, the different services and organizations involved in the VET system and, on one hand the Minister, on the other hand the Agency and the European decision-making structures, regarding the programs of the European Social Fund, initiative programs and the various action programs of the European Union for actions whose objectives are to facilitate the professional integration of persons under twenty-five years. Under the Decree of 17 October 2013, the role of intermediary organization is vested in CCGPE DGEO regarding mobility projects for the benefit of vocational and technical schools. -

Matematisk Statistik 6 Personal 8 Centra Och Andra Enheter 13

Årsberättelse 2011 Stationen Rita i cirklar på Vetenskapsfesti- valens experimentverkstad Foto: Laura Fainsilber Matematiska vetenskaper Chalmers tekniska högskola och Göteborgs universitet 412 96 Göteborg Göteborg, februari 2012 Innehållsförteckning Organisation och personal Matematiska vetenskaper 3 Matematik 4 Matematisk statistik 6 Personal 8 Centra och andra enheter 13 Utbildning Grundutbildning Göteborgs universitet 18 Grundutbildning Chalmers tekniska högskola 21 Forskarutbildning 25 Forskning Forskargrupper och seminarieserier 28 Publikationer 41 Konferenser 52 Gäster och gästforskning 59 Samverkan Projekt 61 Uppdrag 62 Populärvetenskap 63 Ekonomisk rapport Resultaträkning 66 2 Matematiska vetenskaper Ännu ett år har förfl utit. Ett fi nt år sett ur ett verksamhetsperspektiv. Flera personer har blivit speciellt prisade såsom Jeff Steif som tilldelats Eva och Lars Gårdings pris samt Johan Wästlund som förärats med Wallenbergs- priset. Även framgångar inom undervisningen har belönats, Jan-Alve Svensson har erhållit Chalmers stora pedagogiska pris medan Thomas Wernstål fi ck motsvarigheten bland V-teknologerna. Förutom de ovan nämnda pristagarna har fl era gjort strålande forsk- ningsinsatser. Detta gäller även doktorander. Årets forskningsresultat är fullt i nivå med förra årets framgångar uppvisade i en VR-utvärdering. Beträffande engagemang inom styrkeområden har optimeringsgruppen kommit längst, de uppvisar ett stort antal publikationer med styrkeom- rådena Energi och Transport. Inom våra gemensamma forskningfält mel- lan MV och FCC (Fraunhofer Chalmers Centre for Industrial Mathema- tics) förekommer enbart ett ringa samarbete. När det gäller grundutbildningen är våra lärare inte enbart engagerade i undervisningen utan deltar med stor lust i utvecklingen av våra program. I detta sammanhang är det lämpligt att lovorda FCC:s engagemang med att skapa examensarbeten och även delta i handledningen. -

Pdf, 43.47 KB

Rasmus Blanck University of Gothenburg Email: [email protected] Department of Philosophy, Linguistics, and Theory of Science Box 200 40530 Gothenburg, Sweden Education 2017 Ph.D., Logic, University of Gothenburg 2012 Fil. lic., Logic, University of Gothenburg 2009 B.A., Logic, University of Gothenburg Academic employment 2021–2022 Senior lecturer in logic and theoretical philosophy (6 months) Dept. of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg 2021 Senior lecturer in logic and theoretical philosophy (6 months) Dept. of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg 2020–2021 Senior lecturer in logic and theoretical philosophy (6 months) Dept. of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg 2020 Visiting lecturer (6 months) Dept. of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg 2018–2020 Postdoctoral researcher in computational linguistics (2 years) Centre for Linguistic Theory and Studies in Probability Dept. of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg 2017 Lecturer (3 months) Dept. of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg 2012–2013 Lecturer (18 months) Dept. of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg 2006 Lecturer (1 year) Dept. of Philosophy, University of Gothenburg 2004–2005 Lecturer (7 months) Dept. of Philosophy, University of Gothenburg 2003–2016 Part-time fixed-term teacher 9 positions ranging between 20 and 45% of full time, University of Gothenburg Publications 2021 “Hierarchical incompleteness results for arithmetically definable extensions of frag- ments of arithmetic”, accepted for publication in The Review of Symbolic Logic. 2020 “A Logic with Measurable Spaces for Natural Language Semantics” [with J.-P. -

Preliminärantagningen 2021

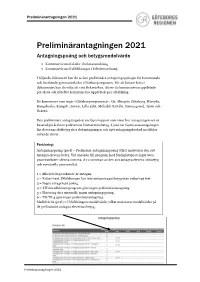

Preliminärantagningen 2021 Preliminärantagningen 2021 Antagningspoäng och betygsmedelvärde • Kommunvis med skolor i bokstavsordning • Kommunvis med utbildningar i bokstavsordning I följande dokument kan du se den preliminära antagningspoängen för kommunala och fristående gymnasieskolor i Göteborgsregionen. För att lättare hitta i dokumentet kan du välja att visa Bokmärken, då ser du kommunerna uppdelade per skola och därefter kommunerna uppdelade per utbildning. De kommuner som ingår i Göteborgsregionen är: Ale, Alingsås, Göteborg, Härryda, Kungsbacka, Kungälv, Lerum, Lilla Edet, Mölndal, Partille, Stenungsund, Tjörn och Öckerö. Den preliminära antagningen är en lägesrapport som visar hur antagningen ser ut baserad på årskurs 9 elevernas höstterminsbetyg. I juni när Gymnasieantagningen får elevernas slutbetyg sker slutantagningen och nytt antagningsbesked meddelas sökande elever. Förklaring: Antagningspoäng (prel) = Preliminär antagningspoäng vilket motsvarar den sist antagna elevens betyg. Vid ansökan till program med färdighetsprov ingår även provresultatet i denna summa, d v s summan av den sist antagna elevens slutbetyg och eventuella provresultat. 1 = Alla behöriga sökande är antagna. 2 = Enbart test. Utbildningen har inte antagning på betyg utan enbart på test. 3 = Ingen antagen på poäng. 4 = Till introduktionsprogram görs ingen preliminärantagning. 5 = Placering sker manuellt, ingen antagningspoäng. 6 = Till TE 4 görs ingen preliminärantagning. Medelvärde (prel) = Utbildningens medelvärde, vilket motsvarar medelvärdet på de preliminärt -

2020 Antagningspoäng Och Medelvärde

Reservantagningen 2020 Reservantagningen 2020 Antagningspoäng och betygsmedelvärde • Kommunvis med skolor i bokstavsordning • Kommunvis med utbildningar i bokstavsordning I följande dokument kan du se reservantagningspoängen för kommunala och fristående gymnasieskolor i Göteborgsregionen. För att lättare hitta i dokumentet kan du välja att visa Bokmärken, då ser du kommunerna uppdelade per skola och därefter kommunerna uppdelade per utbildning. De kommuner som ingår i Göteborgsregionen är: Ale, Alingsås, Göteborg, Härryda, Kungsbacka, Kungälv, Lerum, Lilla Edet, Mölndal, Partille, Stenungsund, Tjörn och Öckerö. Förklaring: Antagningspoäng (reserv) = Reservantagningspoäng, vilket motsvarar den sist antagna elevens betyg. Vid ansökan till program med färdighetsprov ingår även provresultatet i denna summa, d v s summan av den sist antagna elevens slutbetyg och eventuella provresultat. Medelvärde (reserv) = Utbildningens medelvärde, vilket motsvarar medelvärdet av de antagna elevernas slutbetyg. 1 = Alla behöriga sökande är antagna. 2 = Enbart test. Utbildningen har inte antagning på betyg utan enbart på test. 3 = Ingen antagen på poäng. 4= Till introduktionsprogram görs ingen preliminärantagning. 5 = Placering sker manuellt, ingen antagningspoäng. 6 = Meddelas på annat sätt. Reservantagningen 2020 2020-09-07 - Antagningsår 2020 Antagningspoäng Kommun: Ale Antagningspoäng Medelvärde Antagningspoäng Medelvärde Antagningspoäng Medelvärde Utbildning (prel) (prel) (slut) (slut) (reserv) (reserv) Ale gymnasium,Introduktionsprogram IM - Individuellt