Three Key Things in Health Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

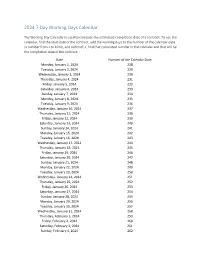

2024 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2024 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Monday, January 1, 2024 228 Tuesday, January 2, 2024 229 Wednesday, January 3, 2024 230 Thursday, January 4, 2024 231 Friday, January 5, 2024 232 Saturday, January 6, 2024 233 Sunday, January 7, 2024 234 Monday, January 8, 2024 235 Tuesday, January 9, 2024 236 Wednesday, January 10, 2024 237 Thursday, January 11, 2024 238 Friday, January 12, 2024 239 Saturday, January 13, 2024 240 Sunday, January 14, 2024 241 Monday, January 15, 2024 242 Tuesday, January 16, 2024 243 Wednesday, January 17, 2024 244 Thursday, January 18, 2024 245 Friday, January 19, 2024 246 Saturday, January 20, 2024 247 Sunday, January 21, 2024 248 Monday, January 22, 2024 249 Tuesday, January 23, 2024 250 Wednesday, January 24, 2024 251 Thursday, January 25, 2024 252 Friday, January 26, 2024 253 Saturday, January 27, 2024 254 Sunday, January 28, 2024 255 Monday, January 29, 2024 256 Tuesday, January 30, 2024 257 Wednesday, January 31, 2024 258 Thursday, February 1, 2024 259 Friday, February 2, 2024 260 Saturday, February 3, 2024 261 Sunday, February 4, 2024 262 Date Number of the Calendar Date Monday, February 5, 2024 263 Tuesday, February 6, 2024 264 Wednesday, February -

Pricing*, Pool and Payment** Due Dates January - December 2021 Mideast Marketing Area Federal Order No

Pricing*, Pool and Payment** Due Dates January - December 2021 Mideast Marketing Area Federal Order No. 33 Class & Market Administrator Payment Dates for Producer Milk Component Final Pool Producer Advance Prices Payment Dates Final Payment Due Partial Payment Due Pool Month Prices Release Date Payrolls Due & Pricing Factors PSF, Admin., MS Cooperative Nonmember Cooperative Nonmember January February 3 * February 13 February 22 December 23, 2020 February 16 ** February 16 February 17 Janaury 25 January 26 February March 3 * March 13 March 22 January 21 * March 15 March 16 March 17 February 25 February 26 March March 31 * April 13 April 22 February 18 * April 15 April 16 April 19 ** March 25 March 26 April May 5 May 13 May 22 March 17 * May 17 ** May 17 ** May 17 April 26 ** April 26 May June 3 * June 13 June 22 April 21 * June 15 June 16 June 17 May 25 May 26 June June 30 * July 13 July 22 May 19 * July 15 July 16 July 19 ** June 25 June 28 ** July August 4 * August 13 August 22 June 23 August 16 ** August 16 August 17 July 26 ** July 26 August September 1 * September 13 September 22 July 21 * September 15 September 16 September 17 August 25 August 26 September September 29 * October 13 October 22 August 18 * October 15 October 18 ** October 18 ** September 27 ** September 27 ** October November 3 * November 13 November 22 September 22 * November 15 November 16 November 17 October 25 October 26 November December 1 * December 13 December 22 October 20 * December 15 December 16 December 17 November 26 ** November 26 December January 5, 2022 January 13, 2022 January 22, 2022 November 17 * January 18, 2022 ** January 18, 2022 ** January 18, 2022 ** December 27 ** December 27 ** * If the release date does not fall on the 5th (Class & Component Prices) or 23rd (Advance Prices & Pricing Factors), the most current release preceding will be used in the price calculation. -

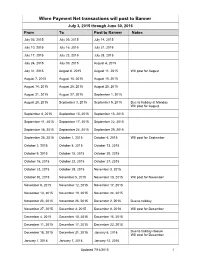

Transactions Posted to Pathway

When Payment Net transactions will post to Banner July 3, 2015 through June 30, 2016 From To Post to Banner Notes July 03, 2015 July 09, 2015 July 14, 2015 July 10, 2015 July 16, 2015 July 21, 2015 July 17, 2015 July 23, 2015 July 28, 2015 July 24, 2015 July 30, 2015 August 4, 2015 July 31, 2015 August 6, 2015 August 11, 2015 Will post for August August 7, 2015 August 13, 2015 August 18, 2015 August 14, 2015 August 20, 2015 August 25, 2015 August 21, 2015 August 27, 2015 September 1, 2015 August 28, 2015 September 3, 2015 September 9, 2015 Due to holiday at Monday Will post for August September 4, 2015 September 10, 2015 September 15, 2015 September 11, 2015 September 17, 2015 September 22, 2015 September 18, 2015 September 24, 2015 September 29, 2015 September 25, 2015 October 1, 2015 October 6, 2015 Will post for September October 2, 2015 October 8, 2015 October 13, 2015 October 9, 2015 October 15, 2015 October 20, 2015 October 16, 2015 October 22, 2015 October 27, 2015 October 23, 2015 October 29, 2015 November 3, 2015 October 30, 2015 November 5, 2015 November 10, 2015 Will post for November November 6, 2015 November 12, 2015 November 17, 2015 November 13, 2015 November 19, 2015 November 24, 2015 November 20, 2015 November 26, 2015 December 2, 2015 Due to holiday November 27, 2015 December 3, 2015 December 8, 2018 Will post for December December 4, 2015 December 10, 2015 December 15, 2015 December 11, 2015 December 17, 2015 December 22, 2015 December 18, 2015 December 31, 2015 January 6, 2016 Due to holiday closure Will post for December -

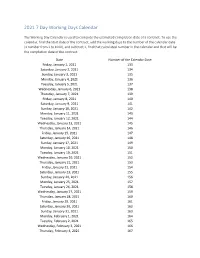

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

PAYROLL PERIODS PAYROLL CALENDAR for Fiscal Year 2022

PAYROLL CALENDAR for Fiscal Year 2022 (July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022) PLEASE NOTE: To ensure payment on the following distribution dates all appropriate paperwork must be received by the due date shown below! PAY Paperwork Time Entry dates Approval Direct Deposit PAYROLL Type, # deadline for employees & Deadline Distribution Dates PERIODS see below to HR originators 11:59 PM DATES SM14 ª³ July 1-15, 2021 7-Jul **Jul 14 Jul-16 Thursday, July 22, 2021 SM15 ª³ July 16-31, 2021 21-Jul Jul 16-31 Aug-02 Friday, August 6, 2021 SM16 ª³ Aug. 1-15, 2021 4-Aug Aug 1-15 Aug-16 Friday, August 20, 2021 SM17 ª Aug. 16-31, 2021 18-Aug Aug 16-31 Sep-01 Tuesday, September 7, 2021 SM18 ª Sept. 1-15, 2021 8-Sep Sep 1-15 Sep-16 Wednesday, September 22, 2021 SM19 ª Sept. 16-30, 2021 22-Sep Sep 16-30 Oct-01 Thursday, October 7, 2021 SM20 ª Oct. 1-15, 2021 6-Oct Oct 1-15 Oct-18 Friday, October 22, 2021 SM21 ª Oct. 16-31, 2021 20-Oct Oct 16-31 Nov-01 Friday, November 5, 2021 SM22 ª Nov. 1-15, 2021 4-Nov Nov 1-15 Nov-16 Monday, November 22, 2021 SM23 ª Nov. 16-30, 2021 18-Nov Nov 16-30 Dec-01 Tuesday, December 7, 2021 SM24 ª Dec. 1- 15, 2021 8-Dec Dec 1-15 Dec-16 Wednesday, December 22, 2021 SM1 Dec. 16-31, 2021 22-Dec Dec 16-31 Jan-03 Friday, January 7, 2022 SM2 ª² Jan. -

September 22, 2020 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Kevin

September 22, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives H-232, U.S. Capitol Building H-204, U.S. Capitol Building Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: We write to express our concerns about the status of ongoing negotiations for a relief package to confront the dual public health and economic crises Americans are facing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. It has been suggested by some that Members of Congress are anxious to return to their districts to campaign in advance of the November 3rd election, even if that means leaving Capitol Hill without passing another COVID-19 relief bill. We want to be very clear that we do not in any way agree with this position. We strongly believe that until the House has successfully sent new, bipartisan COVID-19 relief legislation to the Senate, our place of duty remains here in the People’s House. We were elected to represent the best interests of our constituents and the country. Our constituents' expectations in the midst of this crisis are that we not only rise to the occasion and stay at the table until we have delivered the relief they so desperately need, but also that we set aside electoral politics and place the needs of the country before any one region, faction, or political party. Our constituents do not want us home campaigning while businesses continue to shutter, families struggle to pay the bills, food bank lines lengthen, schools struggle to reopen, pressures grow on hospital systems, and state and local budget shortfalls mean communities consider layoffs for first responders and teachers. -

Pay Week Begin: Saturdays Pay Week End: Fridays Check Date

Pay Week Begin: Pay Week End: Due to UCP no later Check Date: Saturdays Fridays than Monday 7:30am week 1 December 10, 2016 December 16, 2016 December 19, 2016 December 30, 2016 week 2 December 17, 2016 December 23, 2016 December 26, 2016 week 1 December 24, 2016 December 30, 2016 January 2, 2017 January 13, 2017 week 2 December 31, 2016 January 6, 2017 January 9, 2017 week 1 January 7, 2017 January 13, 2017 January 16, 2017 January 27, 2017 week 2 January 14, 2017 January 20, 2017 January 23, 2017 January 21, 2017 January 27, 2017 week 1 January 30, 2017 February 10, 2017 week 2 January 28, 2017 February 3, 2017 February 6, 2017 week 1 February 4, 2017 February 10, 2017 February 13, 2017 February 24, 2017 week 2 February 11, 2017 February 17, 2017 February 20, 2017 March 3, 2017 week 1 February 18, 2017 February 24, 2017 February 27, 2017 ***1 Week Pay Period Transition*** week 1 February 25, 2017 March 3, 2017 March 6, 2017 March 17, 2017 week 2 March 4, 2017 March 10, 2017 March 13, 2017 week 1 March 11, 2017 March 17, 2017 March 20, 2017 March 31, 2017 week 2 March 18, 2017 March 24, 2017 March 27, 2017 week 1 March 25, 2017 March 31, 2017 April 3, 2017 April 14, 2017 week 2 April 1, 2017 April 7, 2017 April 10, 2017 week 1 April 8, 2017 April 14, 2017 April 17, 2017 April 28, 2017 week 2 April 15, 2017 April 21, 2017 April 24, 2017 week 1 April 22, 2017 April 28, 2017 May 1, 2017 May 12, 2017 week 2 April 29, 2017 May 5, 2017 May 8, 2017 week 1 May 6, 2017 May 12, 2017 May 15, 2017 May 26, 2017 week 2 May 13, 2017 May 19, 2017 May -

COVID-19 Update September 22, 2020

COVID-19 Update September 22, 2020 As of September 21, 2020, at 8:30 PM, the total of laboratory-confirmed and probable COVID-19 cases reported among Connecticut residents is 56160, including 53814 laboratory-confirmed and 2346 probable cases. Seventy patients are currently hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19. There have been 4496 COVID-19-associated deaths. In Connecticut during the early months of this pandemic, it became increasingly clear that it would be necessary to track probable COVID-19 cases and deaths, in addition to laboratory-confirmed (RT-PCR) cases and deaths. This was needed to better measure the burden and impact of this disease in our communities and is now part of the national surveillance case definition for COVID-19. Probable cases of COVID-19 involve persons who have not had confirmatory laboratory testing (RT-PCR) performed for COVID-19, but whose symptoms indicate they are likely to have a COVID-19 infection. In Connecticut, most of the probable COVID-19 cases involve persons whose death certificates list COVID-19 disease or SARS-CoV-2 as a cause of death or a significant condition contributing to death. Prior to June 1, probable and confirmed cases were reported together. Overall Summary Total** Change Since Yesterday COVID-19 Cases 56160 +136 COVID-19-Associated Deaths 4496 +1 Patients Currently Hospitalized with COVID-19 70 +2 COVID-19 PCR Tests Reported 1477478 +12044 **Includes confirmed plus probable cases COVID-19 Cases and Associated Deaths by County of Residence As of 09/21/20 8:30pm. COVID-19 -

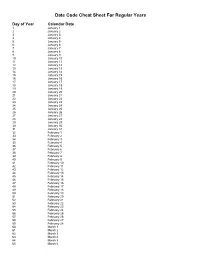

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

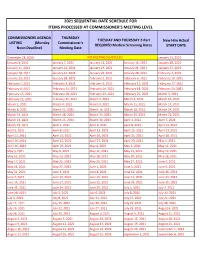

2021 Sequential Date List

2021 SEQUENTIAL DATE SCHEDULE FOR ITEMS PROCESSED AT COMMISSIONER'S MEETING LEVEL COMMISSIONERS AGENDA THURSDAY TUESDAY AND THURSDAY 2-Part New Hire Actual LISTING (Monday Commissioner's REQUIRED Medical Screening Dates START DATE Noon Deadline) Meeting Date December 28, 2020 NO MEETING SCHEDULED January 13, 2021 January 4, 2021 January 7, 2021 January 12, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 20, 2021 January 11, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 19, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 27, 2021 January 18, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 26, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 3, 2021 January 25, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 2, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 10, 2021 February 1, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 9, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 17, 2021 February 8, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 16, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 24, 2021 February 15, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 23, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 3, 2021 February 22, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 2, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 10, 2021 March 1, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 9, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 17, 2021 March 8, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 16, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 24, 2021 March 15, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 23, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 31, 2021 March 22, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 30, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 7, 2021 March 29, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 6, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 14, 2021 April 5, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 13, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 21, 2021 April 12, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 20, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 28, 2021 April 19, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 27, 2021 April -

RG 01.01: Board of Trustees Stored in Black Filing Cabinets in HCC Archives Room # = Some Electronic Files; ! = Missing Minutes

RG 01.01: Board of Trustees Stored in Black Filing Cabinets in HCC Archives Room # = some electronic files; ! = missing minutes Background Information Dates: 1981-present Extent: 6 filing cabinet drawers, 86 MB Name of Creator: Members of the HCC Board of Trustees Language: English Conditions Governing Access: Unrestricted Scope & Content: This sub-series contains meeting agendas, minutes, and associated materials. Administrative/Biographical History: The Board of Trustees was formed in 1981 with the authority of the Board of Regents. The first Chairman of the Board was John T. Hickey. The first meeting of the Board was on March 13, 1981. Originally the board was to meet on the fourth Tuesday of every month. System of Arrangement: Chronologically by year, and then by month. Access Points (keywords): BOT, Board of Trustees, John T. Hickey, David M. Bartley Meeting Minutes and Associated Material 1981 1982 1983 1984 January 5 January 25 January 24 February 23 February 22 February 28 March 13 March 23 March 22 March 27 April 28 April 27 April 26 April 24 May 26 May 25 May 22 June 23 June 22 July 28 July 27 August 25 August 24 August 9 August 7 September 22 September 28 September 27 September 25 October 27 October 26 October 25 October 23 November 23 November 22 November 27 December 22 December 29 1985 1986 1987 1988 January 22 January 28 !January 27 January 26 February 26 February 25 February 24 February 23 March 26 March 25 March 24 March 22 April 23 April 22 April 28 April 26 May 28 May 27 May 26 May 24 June 25 June 24 June 23 June 28 -

Poses of Section 4 of the Act of September 22, 1959, Panagiotis

868 PRIVATE LAW 87-B2-JUNE 21, 1961 [75 ST AT. poses of section 4 of the Act of September 22, 1959, Panagiotis Sotiropoulos shall be deemed to have oeen registered on a consular waiting list pursuant to section 203(c) of the Immigration and 8 use 1153. Nationality Act under a priority date earlier than December 31,1953. Approved June 21, 1961. Private Law 87-52 June 21, 1961 AN ACT [H. R. 210 I] For the relief of Evelina Scarpa. Be it enacted hy the Senate cmd House of Representatives of the Evelina Scarpa. 66 Stat. 166, 180. United States of America in Congress assembled^ That, for the 8 use 110 1, purposes of sections 101(a) (27) (A), and 205 of the Immigration 1155. and Nationalitv Act, Evelina Scarpa shall be held and considered to be the natural-oom alien minor child of Mr, and Mrs. Angelo Scarpa, citizens of the United States: Provided^ That the natursd parents of the beneficiary shall not, by virtue of such parentage, be accorded any right, privilege, or status under the Immigration and Nationality Act. Approved June 21, 1961. Private Law 87-53 June 21, 1961 AN ACT [H. R. 2107] For the relief of Pietro DiGregorio Bruno. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the Pletro DlGrego- rio Bruno. United States of America in Congress assembled^ That, for the 66 Stat. 166, 180. purposes of sections 101(a) (27) (A) and 205 of the Immigration 8 use 1101, 1155. and Nationality Act, the minor cnild, Pietro DiGregorio Bruno, shall be held and considered to be the natural-bom alien child of Mr.