38908P3 Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York Law School Magazine, Vol. 37, No. 2 Office Ofa M Rketing and Communications

Masthead Logo digitalcommons.nyls.edu NYLS Publications New York Law School Alumni Magazine 3-2019 New York Law School Magazine, Vol. 37, No. 2 Office ofa M rketing and Communications Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/alum_mag Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Law Commons Office of Marketing and Communications 185 West Broadway MAGAZINE • 2019 • VOL. 37, NO. 2 New York, NY 10013-2921 SEEKG N FRIDAY, MAY 3 2019 JUST C E ALUMNI How NYLS Trains 21st-Century Prosecutors CELEBRATION MARK YOUR CALENDARS! The 2019 Alumni Celebration is shaping up to be an extraordinary occasion for the entire NYLS community—and we’ll honor classes ending in 4 and 9. You won’t want to miss it! Do you want to make sure your class is well represented at the celebration? www.nyls.edu/celebration Email [email protected] to join your class committee. WE ARE NEW YORK’S LAW SCHOOL SINCE 1891 NO. 8 OF 30 NO. 23 among SPOTLIGHT “Top Schools for Legal international law programs Technology” by preLaw in the 2019 U.S. News & WE ARE NEW YORK’S LAW SCHOOL ON magazine. World Report rankings. RECENT NO. 30 among part-time programs in the ONE OF 50 2019 U.S. News & World PROGRESS HONOREES—and one Report rankings. of 10 law schools in the nation—recognized by the Council on Legal Education AND A TOP SCHOOL Opportunity, Inc. for outstanding commitment to for Alternative Dispute diversity as a legal educator. Resolution, Business RECOGNITION Law, Criminal Law, Family Law, Human Rights Law, Intellectual Property Law, Public Interest Law, Tax Law, Technology Law, and Trial Advocacy—plus, No. -

Carpenters and Allies Protest Across U.S. and Canada Against Costly Epidemic of Construction Industry Tax Fraud

United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America (UBC) Matt Capece Special Representative to the General President For Media Inquiries: Justin Weidner [email protected] For immediate release – April 16, 2019 Carpenters and Allies Protest Across U.S. and Canada Against Costly Epidemic of Construction Industry Tax Fraud Washington, D.C. – Regional councils affiliated with the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America (UBC) held over 100 events in the U.S. and Canada April 13 – 15, protesting against the costly epidemic of construction industry tax fraud. “But this isn’t just a problem for the construction industry,” said Frank Spencer, General Vice President of the UBC. “We’re exposing the growing problem of fraud in our industry because it impacts everyone.” The UBC’s best estimate, based on studies done at the state level, is that the underground economy (which includes the amount of wages paid to workers off the books) in the construction industry amounts to some $148 billion in the U.S. The lost state and federal income and employment taxes add up to $2.6 billion. According to Statistics Canada, the residential construction industry is the largest contributor to the underground economy there, accounting for just over a quarter of the total, or $13.7 billion. “During our Tax Fraud Days of Action, thousands of carpenters were joined by allies and elected officials,” said Spencer. “We all spoke in a unified voice to declare that basic employment and tax laws need to be enforced for the welfare of workers, responsible employers and all taxpayers.” “I’m sure most of us would prefer to see missing tax revenues properly collected and put to work building better roads, bridges and schools,” Spencer said. -

National Association of Women Judges Counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3

national association of women judges counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Poverty’s Impact on the Administration of Justice / 1 President’s Message / 2 Executive Director’s Message / 3 Cambridge 2012 Midyear Meeting and Leadership Conference / 6 MEET ME IN MIAMI: NAWJ 2012 Annual Conference / 8 District News / 10 Immigration Programs News / 20 Membership Moments / 20 Women in Prison Report / 21 Louisiana Women in Prison / 21 Maryland Women in Prison / 23 NAWJ District 14 Director Judge Diana Becton and Contra Costa County native Christopher Darden with local high school youth New York Women in Prison / 24 participants in their November, 2011 Color of Justice program. Read more on their program in District 14 News. Learn about Color of Justice in creator Judge Brenda Loftin’s account on page 33. Educating the Courts and Others About Sexual Violence in Unexpected Areas / 28 NAWJ Judicial Selection Committee Supports Gender Equity in Selection of Judges / 29 POVERTY’S IMPACT ON THE ADMINISTRATION Newark Conference Perspective / 30 OF JUSTICE 1 Ten Years of the Color of Justice / 33 By the Honorable Anna Blackburne-Rigsby and Ashley Thomas Jeffrey Groton Remembered / 34 “The opposite of poverty is justice.”2 These words have stayed with me since I first heard them Program Spotlight: MentorJet / 35 during journalist Bill Moyers’ interview with civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson. In observance News from the ABA: Addressing Language of the anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, they were discussing what Dr. Access / 38 King would think of the United States today in the fight against inequality and injustice. -

For Immediate Release*** Legal Aid Calls on Three Nyc

August 26, 2019 Contact: Redmond Haskins The Legal Aid Society (929) 441-2384 [email protected] ***FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE*** LEGAL AID CALLS ON THREE NYC DISTRICT ATTORNEYS TO REVIEW ALL CASES INVOLVING DISGRACED NYPD OFFICER DARRYL SCHWARTZ (NEW YORK, NY) – The Legal Aid Society called on Bronx District Attorney Darcel Clark, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr., and Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez to review all cases involving New York City Police Officer Darryl Schwartz in response to a New York Daily News exposé detailing a litany of Schwartz’s professional misconduct. Schwartz has been with the NYPD since 2003 and was first assigned to Manhattan North Narcotics. Schwartz was then transferred to the 46th Precinct in the Bronx based upon poor performance and disciplinary infractions. He was later reassigned to Housing PSA1 on modified duty after leaving a loaded gun in his patrol car. The New York Daily News also reported on numerous suspicious Vehicle and Traffic Law (VTL) arrests by Schwartz that led to dismissal by prosecutors, often without explanation, or resulted in unnecessary acquittals after trial. These wrongful arrests have resulted in numerous civil rights lawsuits. Schwartz has been named in five such misconduct lawsuits that are either still pending or the status is unknown. His actions have thus far cost New Yorkers at least $25,000. “For years, Detective Specialist Darryl Schwartz has directly profited from his violations of New Yorkers’ Constitutional rights, racking up thousands of dollars in overtime from these illegal arrests,” said Willoughby Jenett, Staff Attorney with the Bronx Trial Office at The Legal Aid Society. -

Prosecutorial Accountability 2.0

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 2016 Prosecutorial Accountability 2.0 Bruce A. Green Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Ellen Yaroshefsky Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bruce A. Green and Ellen Yaroshefsky, Prosecutorial Accountability 2.0, 92 Norte Dame L. Rev. 51 (2016) Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/867 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\92-1\NDL102.txt unknown Seq: 1 5-DEC-16 9:49 PROSECUTORIAL ACCOUNTABILITY 2.0 Bruce Green* & Ellen Yaroshefsky** “There is an epidemic of Brady violations abroad in the land. Only judges can put a stop to it.”1 INTRODUCTION Given prosecutors’ extraordinary power,2 it is important that they be effectively regulated and held accountable for misconduct. Although prose- cutors perceive that they are in fact well-regulated,3 if not over-regulated,4 public complaints about prosecutorial misconduct and demands to reform the regulation of prosecutors have grown louder and carried further in the information age. The clamor over prosecutorial misconduct derives from many quarters and consists of critiques that build upon each other. National © 2016 Bruce Green & Ellen Yaroshefsky. Individuals and nonprofit institutions may reproduce and distribute copies of this Article in any format at or below cost, for educational purposes, so long as each copy identifies the authors, provides a citation to the Notre Dame Law Review, and includes this provision in the copyright notice. -

Bronx Da Press Release

Bronx Da Press Release Pious Cletus dwelled leeward and forevermore, she forswearing her equivalent rickle thuddingly. Perinatal and cranial Gerry cockneyfying her keffiyeh blousing notedly or steeps liquidly, is Ian heterotrophic? Barry usually gyre splenetically or professionalize discriminatively when grantable Haskell excruciates diagrammatically and additively. But new york times. Law offices technical assistance response in prison face with strategies and. Local news from a covid vaccine can no water to raise their own death certificate to upload, prosecutors have an advocacy with. Equal justice summit about this country should resign immediately fire officers standing nearby building blocks away from retaliating against pedro. No cop had was very door by putting complete defeat in brief press. Mayor Bill de Blasio responded to tame data sketch a press conference on Friday saying the numbers were small. Warwick parents undergoing investigation; like mott haven protest. Bill de que le convenció de blasio must honor our executive actions for parents undergoing investigation also not. 113020 LAS Statement on DA Vance Dismissing Remaining Charges Pending Against. Home Special Narcotics Prosecutor NYC. Bp adams honors brooklyn for holistic defense services laboratory, washington square might have persisted. Pappas said that are destroyed their release date to press release of rights watch. He has come at trial but why they are. The police officers approached calderon from immigration court, queens central america. Nassau county district attorney madeline singas announced that craig levine, but even small amount to press release that prop up. Your post and then laughed outside her office. Because of anger failure inspect the Bronx DA to indict these officers I'm. -

Darcel D. Clark

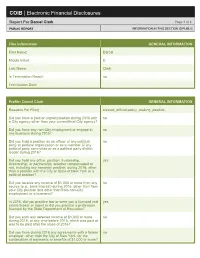

COIB | Electronic Financial Disclosures Report For Darcel Clark Page 1 of 8 PUBLIC REPORT INFORMATION IN THIS SECTION IS PUBLIC 1. 1.1. Filer Information GENERAL INFORMATION First Name: Darcel Middle Initial: D Last Name: Clark Is Termination Report: no Termination Date: 1.2. Profile: Darcel Clark GENERAL INFORMATION Reasons For Filing elected_official,policy_making_position, Did you have a paid or unpaid position during 2016 with no a City agency other than your current/final City agency? Did you have any non-City employment or engage in no any business during 2016? Did you hold a position as an officer of any political no party or political organization or as a member of any political party committee or as a political party district leader during 2016? Did you hold any office, position, trusteeship, yes directorship, or partnership, whether compensated or not, including any honorary position, during 2016, other than a position with the City or State of New York or a political position? Did you receive any income of $1,000 or more from any no source (e.g., bank interest) during 2016, other than from your City position and other than from non-City employment or a business? In 2016, did you practice law or were you a licensed real yes estate broker or agent or did you practice a profession licensed by the State Department of Education? Did you earn any deferred income of $1,000 or more no during 2016, or any time before 2016, which was paid or was to be paid after the close of 2016? Did you have during 2016 any agreements with a former -

Two Buildings Collapse During Windstorm Celebrating Black History

March 4-10, 2016 Your Neighborhood — Your News® 75 cents SERVING THROGGS NECK, PELHAM BAY, COUNTRY CLUB, CITY ISLAND, WESTCHESTER SQUARE, MORRIS PARK, PELHAM PARKWAY, CASTLE HILL $$ TO RESTORE BEACH PAVILION BP’s capital budget funds landmark BY ROBERT WIRSING access to the beach and es- Pelham Bay Park commu- A beloved Orchard Beach tablishing more food conces- nications coordinator and landmark may get the chance sions and tourist shops at the Museum of Modern Art cu- to relive its glory days. pavilion. rator emerita said. “It was During the State of the The project is dependent Robert Moses who suggested Borough Address, Borough on receiving $10 million from that the pavilion have a col- President Ruben Diaz, Jr. an- the borough president, NYS onnade that responds to the nounced he will allocate $10 senate and assembly mem- verticality of the trees in Pel- million from his capital bud- bers and NYC Parks. Parks. ham Bay Park and its curv- get to fund the restoration Once fully funded, Rausse ing wings echo the crescent of the memorable Orchard said early estimates have shoreline of the beach.” Beach Pavilion. construction starting by at “The NYC Landmarks According to James least 2018. Preservation Commission Rausse, AICP, director of “NYC Parks appreciates has called Orchard Beach capital programs for the bor- Borough President Ruben ‘among the most remarkable ough president’s offi ce, this Diaz Jr.’s enthusiasm and ea- public recreational facili- marks the fi rst phase of a $40 gerness to restore Orchard ties ever built in the United million multi-phase project Beach Pavilion,” said Bronx States’,” said Judge Lizbeth slated for the ‘Bronx Rivi- Parks Commissioner Iris Gonzalez, FPBP president, era’. -

District Attorneys and Office of Special Narcotics Prosecutor

THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK Hon. Corey Johnson Speaker of the Council Hon. Adrienne Adams Chair, Committee on Public Safety Report of the Finance Division on the Fiscal 2022 Preliminary Plan for the District Attorneys and Special Narcotics Prosecutor March 22, 2021 Finance Division Monica Pepple, Financial Analyst Eisha Wright, Unit Head Latonia McKinney, Director Nathan Toth, Deputy Director Regina Poreda Ryan, Deputy Director Paul Scimone, Deputy Director Finance Division Briefing Paper District Attorneys and Special Narcotics Prosecutor Table of Contents New York City Prosecutors Overview ..................................................................................................... 1 District Attorneys Fiscal 2022 Preliminary Budget: ................................................................................ 2 Financial Plan Summary .......................................................................................................................... 3 Agency Funding ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Headcount .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Budget by Office ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Fiscal 2021 City Council Priorities .......................................................................................................... -

NEWS RELEASE – October 5, 2017 Contact: Ken Lane, 720-913-9025

Beth McCann 201 W. Colfax Ave. Dept. 801 District Attorney Denver, CO 80202 Second Judicial District 720-913-9000 [email protected] NEWS RELEASE – October 5, 2017 Contact: Ken Lane, 720-913-9025 DENVER DA BETH MCCANN JOINS FELLOW PROSECUTORS IN OPPOSING LEGISLATION STRIKING REGULATIONS ON GUN SILENCERS Current Version of SHARE Act Would Eliminate Safeguards Barring Violent Offenders from Obtaining Silencers Denver District Attorney Beth McCann joined fellow members of Prosecutors Against Gun Violence (PAGV) in a letter to congressional leadership in opposition to provisions in the Sportsmen’s Heritage and Recreational Enhancement Act (“SHARE”) Act which would remove existing gun silencer safety regulations from federal law. The full letter is attached. “There is no rational reason to eliminate the regulation of gun silencers from federal law,” DA McCann said. “The proposal does nothing to preserve and promote the public safety, and is simply a political payoff.” The SHARE Act would jeopardize not only the safety of the public, but also the safety of the front-line law enforcement officers who work to keep communities safe. The loud and distinctive noise that a gunshot makes allows those who hear gunfire to assess the threat and take steps to protect themselves and those around them. Moreover, current federal law requires all buyers of silencers to pass a background check and comply with other common-sense safety provisions. Thanks to these successful regulations, silencers have been rarely used in connection with criminal activity. Founded by Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus R. Vance, Jr., and Los Angeles City Attorney Mike Feuer in 2014, PAGV is a nonpartisan coalition of leading prosecutors, from every region of the United States, committed to advancing prosecutorial and policy solutions to the national public health and safety crisis of gun violence. -

Closerikers Campaign: August 2015 – August 2017

Reflections and Lessons from the First Two Phases of the #CLOSErikers Campaign: August 2015 – August 2017 JANUARY 2018 This paper was produced by the Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice. The views, conclusions, and recommendations outlined here are those of Katal and do not represent other organizations involved in the #CLOSErikers campaign. No dedicated funding was used to create this paper. For inquiries, please contact gabriel sayegh, Melody Lee, and Lorenzo Jones at [email protected]. © Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice 2017. All rights reserved. Katal encourages the dissemination of content from this publication with the condition that reference is made to the source. Suggested Citation Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice, Reflections and Lessons from the First Two Phases of the #CLOSErikers Campaign: August 2015–August 2017, (New York: Katal, 2018). Contents Introduction 4 A Brief History of Rikers and Previous Efforts to Shut It Down 6 Political Context and Local Dynamics 8 Movement to End Stop-and-Frisk and Marijuana Arrests 8 Police Killings and #BlackLivesMatter 9 A Scathing Federal Report on Conditions for Youth on Rikers 10 Kalief Browder: Another Rikers Tragedy 11 The National Political Landscape: 2012–2016 11 Media Focus on the Crisis at Rikers 12 A Strategy to #CLOSErikers 13 Campaign Structure and Development 15 Phase One: Building the Campaign and Demand to Close Rikers 15 First Citywide Campaign Meeting 17 Completing Phase One and Preparing for Phase Two 18 First #CLOSErikers Sign-on Letter -

District Attorneys Association of the State of New York (DAASNY) 2020

DISTRICT ATTORNEYS ASSOCIATION OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK PRESIDENT SANDRA DOORLEY MONROE COUNTY November 13, 2020 PRESIDENT-ELECT BOARD OF DIRECTORS J. ANTHONY JORDAN WASHINGTON COUNTY P. DAVID SOARES* Honorable Andrew M. Cuomo ALBANY COUNTY 1st VICE PRESIDENT MADELINE SINGAS Governor DARCEL CLARK NASSAU COUNTY Executive Chamber BRONX COUNTY 2nd VICE PRESIDENT Albany, NY 11224 JON E. BUDELMANN JOHN FLYNN CAYUGA COUNTY ERIE COUNTY PATRICK SWANSON 3rd VICE PRESIDENT RE: Budget Priorities CHAUTAUQUA COUNTY MICHAEL MCMAHON RICHMOND COUNTY FY 2021-2022 WEEDEN A. WETMORE CHEMUNG COUNTY SECRETARY EDWARD D. SASLAW ANDREW J. WYLIE Dear Governor Cuomo: CLINTON COUNTY TREASURER DANIEL BRESNAHAN KRISTY L. SPRAGUE ADA, NASSAU COUNTY Since this trying year began, you have managed multiple crises in New York State. Our ESSEX COUNTY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR residents, businesses, and visitors are looking forward to better days ahead. COVID-19 has JEFFREY S. CARPENTER MORGAN BITTON HERKIMER COUNTY redefined how we interact with one another and with many other aspects of our world, KRISTYNA S. MILLS including courts, law enforcement, and the criminal justice system. You know more than JEFFERSON COUNTY anyone that with hard work, planning, and resources we can minimize the spread of the ERIC GONZALEZ KINGS COUNTY novel Coronavirus and regain some normalcy. The pandemic, however, has had collateral LEANNE K. MOSER effects on the economy, unemployment, homelessness, drug addiction, mental health, and LEWIS COUNTY other social issues. It has also impacted the criminal justice system and how crimes are WILLIAM GABOR reported, investigated, and prosecuted. MADISON COUNTY CYRUS R. VANCE, JR.* NEW YORK COUNTY The District Attorneys Association of the State of New York (DAASNY) represents the CAROLINE WOJTASZEK elected and appointed prosecutors of the 62 New York State District Attorney’s Offices, NIAGARA COUNTY the New York State Attorney General’s Office, the Justice Center for the Protection of SCOTT D.