The Development and Application of Water Governance Matrix: a Case of Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PPB GROUP (PEP MK, PEPT.KL) 11 Dec 2020

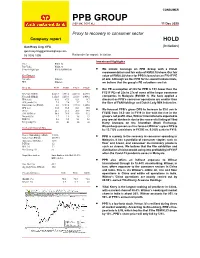

CONSUMER PPB GROUP (PEP MK, PEPT.KL) 11 Dec 2020 Proxy to recovery in consumer sector Company report HOLD Gan Huey Ling, CFA (Initiation) [email protected] 03 2036 2305 Rationale for report: Initiation Investment Highlights Price RM18.74 Fair Value RM20.30 52-week High/Low RM19.96/RM15.00 We initiate coverage on PPB Group with a HOLD recommendation and fair value of RM20.30/share. Our fair Key Changes value of RM20.30/share for PPB is based on an FY21F PE Fair value Initiation of 22x. Although we like PPB for its sound fundamentals, EPS Initiation we believe that the group’s PE valuations are fair. YE to Dec FY19 FY20E FY21F FY22F Our PE assumption of 22x for PPB is 15% lower than the Revenue (RMmil) 4,683.8 3,952.6 4,492.0 4,691.0 FY21F PEs of 25x to 27x of some of the larger consumer Net profit (RMmil) 1,152.6 1,239.8 1,310.8 1,404.1 companies in Malaysia (Exhibit 1). We have applied a EPS (sen) 81.0 87.1 92.1 98.7 discount as PPB’s consumer operations are smaller than EPS growth (%) 7.2 7.6 5.7 7.1 the likes of F&N Holdings and Dutch Lady Milk Industries. Consensus net (RMmil) 0.0 1,152.0 1,291.0 1,345.0 DPS (sen) 31.0 33.0 34.0 35.0 PE (x) 23.1 21.5 20.3 19.0 We forecast PPB’s gross DPS to increase to 33.0 sen in EV/EBITDA (x) 58.8 78.9 55.8 51.2 FY20E from 31.0 sen in FY19 in line with the rise in the Div yield (%) 1.7 1.8 1.8 1.9 group’s net profit. -

Simplified Consolidated Statements of Financial Position

SIMPLIFIED CONSOLIDATED STATEMENTS OF FINANCIAL POSITION Expansion Consistency THE VALUE PROPOSITION STORY OF PPB GROUP is about how PPB Group’s heritage of values and culture translate to growth, Growth consistency and care. The enduring passion of everyone within the Group has helped build a strong customer base and supportive stakeholders. Today, we are equally proud and humbled to tell the story of PPB Group’s value proposition. Quality Passion Care The Corporation 001 OUR PRODUCTS, OUR VALUE PROPOSITION. CONTENTS THE CORPORATION 008 Chairman’s Statement 016 Group Financial Highlights THE 017 Simplified Consolidated Statements FINANCIALS Of Financial Position 018 Directors’ Profiles 054 5-Year Group Financial Statistics 022 Group Corporate Structure 056 Segmental Analysis 024 Corporate Information 057 Share Performance 025 PPB’s Corporate Events And Investor Relations Activities 058 Additional Financial Information 026 Financial Calendar 059 Directors’ Responsibility 027 Corporate Governance Statement Statement 036 Audit Committee Report 060 Directors’ Report 039 Statement On Risk Management And Internal Control 041 Corporate Sustainability Statement 050 Additional Compliance Information THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 066 Consolidated Income Statement 067 Consolidated Statement Of Comprehensive Income 068 Consolidated Statement Of Financial Position THE 070 Consolidated Statement Of Changes In Equity PROPERTIES & SHAREHOLDINGS 072 Consolidated Statement Of Cash Flows 074 Income Statement 164 Properties Owned By PPB And Its Subsidiaries 074 -

Malaysian Invited Companies Company Name Country Robecosam Industry AMMB Holdings Bhd Malaysia BNK Banks Astro Malaysia Holdings

Malaysian invited companies Company_Name Country RobecoSAM_Industry AMMB Holdings Bhd Malaysia BNK Banks Astro Malaysia Holdings Bhd Malaysia PUB Media Axiata Group Bhd Malaysia TLS Telecommunication Services Batu Kawan Bhd Malaysia CHM Chemicals British American Tobacco Malaysia Bhd Malaysia TOB Tobacco Bumi Armada Bhd Malaysia OIE Energy Equipment & Services CIMB Group Holdings Bhd Malaysia BNK Banks Dialog Group Bhd Malaysia CON Construction & Engineering Digi.com Bhd Malaysia TLS Telecommunication Services Felda Global Ventures Holdings Bhd Malaysia FOA Food Products Gamuda Bhd Malaysia CON Construction & Engineering Genting Bhd Malaysia CNO Casinos & Gaming Genting Malaysia Bhd Malaysia CNO Casinos & Gaming Hong Leong Bank Bhd Malaysia BNK Banks Hong Leong Financial Group Bhd Malaysia BNK Banks IHH Healthcare Bhd Malaysia HEA Health Care Providers & Services IJM Corp Bhd Malaysia CON Construction & Engineering IOI Corp Bhd Malaysia FOA Food Products IOI Properties Group Bhd Malaysia REA Real Estate Kuala Lumpur Kepong Bhd Malaysia FOA Food Products Lafarge Malaysia Bhd Malaysia COM Construction Materials Malayan Banking Bhd Malaysia BNK Banks Malaysia Airports Holdings Bhd Malaysia TRA Transportation and Transportation Infrastructure Maxis Bhd Malaysia TLS Telecommunication Services MISC Bhd Malaysia TRA Transportation and Transportation Infrastructure Nestle Malaysia Bhd Malaysia FOA Food Products Petronas Chemicals Group Bhd Malaysia CHM Chemicals Petronas Dagangan BHD Malaysia OIX Oil & Gas Petronas Gas BHD Malaysia GAS Gas Utilities -

Financial Hegemony, Diversification Strategies and the Firm Value of Top 30 FTSE Companies in Malaysia

Asian Social Science; Vol. 12, No. 3; 2016 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Financial Hegemony, Diversification Strategies and the Firm Value of Top 30 FTSE Companies in Malaysia Wan Sallha Yusoff1, Mohd Fairuz Md. Salleh2, Azlina Ahmad2 & Norida Basnan2 1 School of Business Innovation and Technopreneurship, Universiti Malaysia Perlis, Malaysia 2 School of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Management, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia Correspondence: Wan Sallha Yusoff, School of Business Innovation and Technopreneurship, Universiti Malaysia Perlis, Malaysia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 8, 2015 Accepted: January 18, 2016 Online Published: February 23, 2016 doi:10.5539/ass.v12n3p14 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v12n3p14 Abstract This study investigates the relationships between financial hegemony groups, global diversification strategies and firm value of the Malaysia’s 30 largest companies listed in FTSE Bursa Malaysia Index Series during 2009 to 2012 period. We chose Malaysia as an ideal setting because the findings contribute to the phenomenon of the diversification–performance relationship in the Southeast Asian countries. We apply hegemony stability theory to explain the importance of financial hegemony groups in deciding international locations for operations. By using panel data analysis, we find that financial hegemony groups are significantly important in international location decisions. Results reveal that the stability of financial hegemony in BRICS and G7 groups enhances the financial value of the Malaysia’s 30 largest companies, whereas the stability of financial hegemony in ASEAN groups is able to enhance the non-financial value of the firms. -

PROMOTION of ARTS & CULTURE ”Music Can Communicate in a Few Notes a Message That Would Take a Thousand Speeches to Deliver

PROMOTION OF ARTS & CULTURE ”Music can communicate in a few notes a message that would take a thousand speeches to deliver. Music is the literature of the heart and gives us joy where words cannot reach.” – Tan Sri Dato’ (Dr) Francis Yeoh Sock Ping, CBE, FICE, Managing Director of YTL Corporation Berhad 56 YTL CORPORATION BERHAD CORPORATE EVENTS 20 OCT 2016 UNVEILING OF NEW KLIA TRANSIT TRAINS Express Rail Link Sdn Bhd, a 45% associate of YTL Corporation Berhad, unveiled its new KLIA Transit train at its depot in Salak Tinggi, officiated by Malaysia’s Minister of Transport, YB Dato’ Sri Liow Tiong Lai. The six new train- sets, manufactured by CRRC Changchun Railway Vehicles Company Limited, will increase total service capacity by fifty percent. From left to right, Tan Sri Dato’ Seri (Dr) Yeoh Tiong Lay, Executive Chairman of YTL Corporation Berhad; YB Dato’ Sri Liow Tiong Lai, Minister of Transport; YB Datuk Ab Aziz Kaprawi, Deputy Minister of Transport; Tan Sri Mohd Nadzmi Mohd Salleh, Executive Chairman of Express Rail Link Sdn Bhd; and Puan Noormah Mohd Noor, Chief Executive Officer of Express Rail Link Sdn Bhd. 27 OCT 2016 ISETAN’S 1ST INTERNATIONAL FLAGSHIP JAPAN STORE OPENS IN LOT 10 SHOPPING CENTRE Isetan Mitsukoshi Holdings Ltd, Japan’s largest department store group, launched its first flagship Japan Store outside of Tokyo in Lot 10 Shopping Centre. Based on the ‘Cool Japan’ concept and occupying the store’s six floors, with a total floor area of about 11,000 square meters, the store features a range of high-quality and designer products from around Japan. -

ESG Ratings of Plcs Assessed by FTSE Russell# in Accordance with FTSE Russell ESG Ratings Methodology

ESG Ratings of PLCs assessed by FTSE Russell# in accordance with FTSE Russell ESG Ratings Methodology Definition Top 25% by ESG Ratings amongst PLCs in FBM EMAS that have been assessed by FTSE Russell Top 26-50% by ESG Ratings amongst PLCs in FBM EMAS that have been assessed by FTSE Russell Top 51%- 75% by ESG Ratings amongst PLCs in FBM EMAS that have been assessed by FTSE Russell Bottom 25% by ESG Ratings amongst PLCs in FBM EMAS that have been assessed by FTSE Russell Stock Company Name Sector F4GBM ESG Grading Code (sorted By Alphabetical) Index Band 6599 AEON CO. (M) BHD CONSUMER PRODUCTS & SERVICES ** 5139 AEON CREDIT SERVICE (M) BHD FINANCIAL SERVICES Yes *** 7078 AHMAD ZAKI RESOURCES BHD CONSTRUCTION *** 5099 AIRASIA GROUP BERHAD CONSUMER PRODUCTS & SERVICES *** 5238 AIRASIA X BERHAD CONSUMER PRODUCTS & SERVICES ** 2658 AJINOMOTO (M) BHD CONSUMER PRODUCTS & SERVICES Yes *** 2488 ALLIANCE BANK MALAYSIA BERHAD FINANCIAL SERVICES Yes *** 5293 AME ELITE CONSORTIUM BERHAD CONSTRUCTION * 1015 AMMB HOLDINGS BHD FINANCIAL SERVICES Yes **** 6556 ANN JOO RESOURCES BHD INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTS & SERVICES * 6399 ASTRO MALAYSIA HOLDINGS BERHAD TELECOMMUNICATIONS & MEDIA Yes **** 6888 AXIATA GROUP BERHAD TELECOMMUNICATIONS & MEDIA Yes *** 5106 AXIS REITS REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT TRUSTS ** 3395 BERJAYA CORPORATION BHD INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTS & SERVICES ** 1562 BERJAYA SPORTS TOTO BHD CONSUMER PRODUCTS & SERVICES ** 5248 BERMAZ AUTO BERHAD CONSUMER PRODUCTS & SERVICES Yes **** 2771 BOUSTEAD HOLDINGS BHD INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTS & SERVICES ** 4162 BRITISH AMERICAN -

ASEAN Asset Class Publicly Listed Companies 2019 (Score 97.50 Points and Above - by Alphabetical Order)

ASEAN Asset Class Publicly Listed Companies 2019 (score 97.50 points and above - by alphabetical order) NAME OF PUBLICLY LISTED COMPANY COUNTRY 1 2GO GROUP, INC. Philippines 2 ADVANCE INFO SERVICE PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 3 AIRPORTS OF THAILAND PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 4 ALLIANCE BANK MALAYSIA BHD Malaysia 5 ALLIANZ MALAYSIA BHD Malaysia 6 AMATA CORPORATION PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 7 AMMB HOLDINGS BHD Malaysia 8 ASTRO MALAYSIA HOLDINGS BERHAD Malaysia 9 AXIATA GROUP BERHAD Malaysia 10 AYALA CORPORATION Philippines 11 AYALA LAND, INC. Philippines 12 BANGCHAK CORPORATION PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 13 BANGKOK AVIATION FUEL SERVICES PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 14 BANK OF AYUDHYA PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 15 BANK OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS Philippines 16 BDO UNIBANK, INC. Philippines 17 BELLE CORPORATION Philippines 18 BIMB HOLDINGS BHD Malaysia 19 BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO (MALAYSIA) BHD Malaysia 20 BURSA MALAYSIA BHD Malaysia 21 CAHYA MATA SARAWAK BHD Malaysia 22 CAPITALAND LIMITED Singapore 23 CENTRAL PATTANA PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 24 CHAROEN POKPHAND FOODS PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 25 CHINA BANKING CORPORATION Philippines 26 CIMB GROUP HOLDINGS BHD Malaysia 27 CITY DEVELOPMENTS LIMITED Singapore 28 COL PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 29 COMFORTDELGRO CORP LIMITED Singapore 30 DBS GROUP HOLDINGS LTD Singapore NAME OF PUBLICLY LISTED COMPANY COUNTRY 31 DIGI.COM BHD Malaysia 32 DMCI HOLDINGS, INC. Philippines 33 EASTERN WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT PCL. Thailand 34 ELECTRICITY GENERATING PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 35 FAR EAST ORCHARD LIMITED Singapore 36 FRASER AND NEAVE LIMITED Singapore 37 FRASERS PROPERTY LIMITED Singapore 38 GLOBAL POWER SYNERGY PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Thailand 39 GLOBE TELECOM, INC. -

Hong Leong Bank Berhad

January 9, 2019 Global Markets Research Fixed Income Fixed Income Daily Market Snapshot UST US Treasuries Tenure Closing (%) Chg (bps) US Treasuries dipped yet again yesterday for the 3rd session; 2-yr UST 2.59 4 causing yields led by the front-end to settle sharply higher as the 5-yr UST 2.58 4 curve continued flattening. Overall benchmark yields ended 2-4bps 10-yr UST 2.73 3 higher with the 2Y spiking by 4bps at 2.59% whilst the much- 30-yr UST 3.01 2 watched 10Y ended 3bps up at 2.73%. The first coupon sale auction for 2019 saw $38b of 3Y notes end with a weaker BTC ratio MGS GII* of 2.44x versus previous six auction average of 2.59x. Meanwhile, investors and analysts concerns remain on the inversion and parish Tenure Closing (%) Chg (bps) Closing (%) Chg (bps) yield levels on the front-end of the curve on lesser rate hike 3-yr 3.57 0 3.64 0 possibility and optimsm of trade talks between US and China. 5-yr 3.73 0 3.80 -1 7-yr 3.98 0 4.04 0 MGS/GII 10-yr 4.07 0 4.19 -4 Trading momentum in local govvies maintained traction on high 15-yr 4.38 0 4.49 -3 volume of RM4.16b amid a solid 10Y GII bond auction with interest 20-yr 4.59 1 4.72 -1 seen maily in both the old and current 10Y benchmark GII/MGS 30-yr 4.79 -2 4.91 0 bonds followed by the shorter off-the-run 19’s and 24’s. -

Executive Summary

BM056-3-5.2-FMGT Individual Assignment Asian Pacific University EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This documentation provides two companies within Bursa Malaysia (KLSE), representing two different sectors. Astro Holdings Berhad is a leading integrated consumer media entertainment group and is classified under the trading and serve sector. Sunway Berhad is engaged in two businesses: property and construction and is classified under the infrastructure sector. Both companies financial sources/resource are obtained from Bank loans and shareholders. In addition, Astro and Sunway Berhad have a significant amount of debt however, Astro has a reduced debt amount as compared to Sunway, with Astro sitting on RM3671 million while Sunway sits on RM2.33 billion. Astro’s debt profile is categorized into three (3) main contributors; USD term loan, RM term loan and Finance lease. It seems that Astro and Sunway have different challenges that are being faced. Astro’s operating expenses will peak in FY14 as the company focuses on reinvesting for growth. On the other hand, Sunway’s Group’s balance sheet is expected to weaken further as it gears up for property development and to build up its investment properties portfolio. Sunway Berhad’s debts are projected to rise between RM2.91 billion and RM3.30 billion in the next 1-2 years (according to RAM holdings Berhad 2012). This documentation will included important figures and tables such as the company’s liabilities, Assets, debts profile, financial ratio’s, institutional shareholders, financial summary and total debts of -

Corporate Earnings Improved in 2Q

Headline Corporate earnings improved in 2Q MediaTitle The Malaysian Reserve Date 03 Sep 2021 Language English Circulation 12,000 Readership 36,000 Section Companies Page No 10 ArticleSize 399 cm² Journalist S BIRRUNTHA PR Value RM 12,569 Corporate earnings improved in 2Q Expectations of a more robust commented the FBM KLCI component stocks delivered a set of 2Q21 results that recovery in the coming quarters had yet to show meaningful improvement could be on hold sequentially. He views this as due to the reintroduc- by S BIRRUNTHA tion of various pandemic restrictions against a backdrop of surging Covid-19 THE corporate sector's second-quarter infections which weighed on corporate (2Q) financial results reporting season financial performance. appears to be healthier in terms of face According to Ng, six FBM KLCI compo- value, with the number of companies nent stocks, namely, CIMB Group Holdings meeting and/or exceeding expectations Bhd (lower operating expenditure), Sime trumping those that missed, Public Invest- Darby Group Bhd (stronger vehicle and ment Bank Bhd (Publiclnvest) stated results heavy equipment sales), Sime Darby Plan- from the banking, plantation and consu- tation Bhd (higher crude palm oil prices), mer sectors exceeded expectations. IHH Healthcare Bhd (Covid-19-related "A closer look into the results will reveal patients and effective cost-saving initia- some extremes. Be it a function of over- •S^SL, * tives), Petronas Chemicals Group Bhd pessimism or under-estimation, results (higher product prices) and Tenaga Nasional -

Ac 2021 61.Pdf

Accounting 7 (2021) 1033–1048 Contents lists available at GrowingScience Accounting homepage: www.GrowingScience.com/ac/ac.html Can investors benefit from corporate social responsibility and portfolio model during the Covid19 pandemic? Ternence T. J. Tana* and Baliira Kalyebarab aFaculty of Business, Economics and Social Development, University of Malaysia Terengganu, Kuala Nerus, Terengganu, Malaysia bDepartment of Accounting and Finance, School of Business, American University of Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates C H R O N I C L E A B S T R A C T Article history: Since late 2019 and throughout 2020, the global economy has been experiencing difficult times due Received: November 15, 2020 to the outbreak of the lethal Coronavirus (COVID-19). This study looks at the financial impact of Received in revised format: this epidemic on the global economy using Malaysian market index i.e., FTSE Bursa Malaysia KLCI January 28 2021 before and during COVID-19. Measuring the financial impact of this epidemic on the Malaysia Accepted: March 2, 2021 Available online: economy may help policy makers to develop measures to avert similar financial catastrophic impacts March 2, 2021 on the global economy. The study uses Sharpe optimal and naïve diversification model to solve a scenario that factors in the level of corporate social responsibility (CSR) exhibited before and during Keywords: Corporate Social Responsibility the epidemic to measure the financial impact on the stock portfolio. The results show that the Naïve Diversification emergence of COVID-19exacerbated the already weak Malaysian economy. Our findings may help Optimal Portfolio the policy makers in Malaysia to develop and maintain techniques and policies that may mitigate the Sharpe Ratio negative financial impact and handle similar epidemics in the future. -

FTSE Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 28 October 2020 FTSE Malaysia Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 27 October 2020 Constituent Index weight (%) Country Constituent Index weight (%) Country Constituent Index weight (%) Country AirAsia Group Berhad 0.16 MALAYSIA Hong Leong Bank 1.83 MALAYSIA Press Metal Aluminium Holdings 2.07 MALAYSIA Alliance Bank Malaysia 0.48 MALAYSIA Hong Leong Financial 0.66 MALAYSIA Public Bank BHD 9.5 MALAYSIA AMMB Holdings 1.1 MALAYSIA IHH Healthcare 2.99 MALAYSIA QL Resources 1.31 MALAYSIA Astro Malaysia Holdings 0.22 MALAYSIA IJM 0.87 MALAYSIA RHB Bank 1.3 MALAYSIA Axiata Group Bhd 2.49 MALAYSIA IOI 2.73 MALAYSIA Sime Darby 1.65 MALAYSIA British American Tobacco (Malaysia) 0.27 MALAYSIA IOI Properties Group 0.31 MALAYSIA Sime Darby Plantation 3.39 MALAYSIA CIMB Group Holdings 4.14 MALAYSIA Kuala Lumpur Kepong 2.05 MALAYSIA Sime Darby Property 0.38 MALAYSIA Dialog Group 3.3 MALAYSIA Malayan Banking 8.28 MALAYSIA Telekom Malaysia 0.93 MALAYSIA Digi.com 2.8 MALAYSIA Malaysia Airports 0.74 MALAYSIA Tenaga Nasional 7.53 MALAYSIA FGV Holdings 0.41 MALAYSIA Maxis Bhd 2.65 MALAYSIA Top Glove Corp 8.82 MALAYSIA Fraser & Neave Holdings 0.64 MALAYSIA MISC 1.9 MALAYSIA Westports Holdings 0.8 MALAYSIA Gamuda 1.48 MALAYSIA Nestle (Malaysia) 1.69 MALAYSIA YTL Corp 0.72 MALAYSIA Genting 1.34 MALAYSIA PETRONAS Chemicals Group Bhd 3.28 MALAYSIA Genting Malaysia BHD 1.11 MALAYSIA Petronas Dagangan 1.18 MALAYSIA Hap Seng Consolidated 0.93 MALAYSIA Petronas Gas 1.79 MALAYSIA Hartalega Holdings Bhd 5.25 MALAYSIA PPB Group 2.49 MALAYSIA Source: FTSE Russell 1 of 2 28 October 2020 Data Explanation Weights Weights data is indicative, as values have been rounded up or down to two decimal points.