Callaway Golf Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caddie Flyer 8.5X11 20180112.3

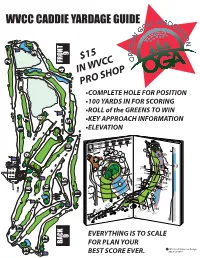

WVCC CADDIE YARDAGE GUIDE $15 VCC IN W PRO SHOP •COMPLETE HOLE FOR POSITION •100 YARDS IN FOR SCORING •ROLL of the GREENS TO WIN •KEY APPROACH INFORMATION •ELEVATION Yellow Orange White Blue 423 Black 464 1 517 1 55 1 30 47 4 yard 6 1 2 6 3 7 29 hdcp 1 PAR 5 N 50 ’ 100 5 0 G 30 5 N I T 126 1 Boulder T I F 4 29 140 123 2 2 3 240 14 153 Oak 7 150 216 200 Boulder Oak 50 200 27 285 blu 350 blk 325 blu 400 blk 285 blu Carry 160 Oak 200 350 350 blk from wht 250 Carry from wht 275 from wht C 2017 C 2017 ’ 0 2 EVERYTHING IS TO SCALE FOR PLAN YOUR C 2018 Scott Peterson Design BEST SCORE EVER. 503-612-1717 My hope is that you can use this information to get the most of your time Playing WVCC. This is an exact user guide to the course. You can liter- ally plan which clubs to use on each hole before show- ing up. 0 33 1’ Straight putts on green, 32 14 slope direction 50 Exact location of water, hazard… 24 3’ 5’ 50 100 100 B 100 YARD Slope on fairways 150 A 150 YARD Sand Trap diculty rating 150 Graphic showing the diculty of humps 200 and drop os around greens 200 WVCC amenities, Club house, Practice 250 Areas, Drinking Water, Rest Room… Exact location of trees 300 (not graphic eye candy) From Tees to 300 Marker A B 5’ Ylw 95 142 350 Org 91 139 Wht 140 187 Blu 182 227 400 Tee Marker to First challenge Blk 247 292 3’ on that Hole 450 Tee Marker to First challenge on that Hole Elevation along the length of the hole Ruler matching the scale on each hole C 2018 Scott Peterson Design 503-612-1717 CADDIE COURSE GUIDE YARDAGE, FAIRWAY ELEVATION, GREEN SLOPE -

JULY 2021 Message from the Director of Golf

JULY 2021 Message from the Director of Golf Rick Price, PGA This time of the year, hydration is extremely important during the summer heat. Let’s also be prepared for thunderstorms, flash floods, and lightning. It’s official “Monsoon Season” in Southern Arizona, which means we need to be careful. Be sure to follow the following suggestions to keep yourself safe while heading out on the course during the monsoon season. Check the forecast and check it often. Download a reliable radar app, seek shelter immediately if you’re not able to get off the golf course in time. Don’t worry if you can’t finish your round; we are happy to give you a rain check “credit” to complete your round another time. The important thing is to be safe and use your best judgment when the weather is questionable. How to Purchase or Renew a Membership It’s the start of our fiscal year and time to renew or purchase a membership. If this is your first time purchasing an annual membership, visit the Pro Shop or call for more information. To renew an Annual Membership, you can go online to www.theviewsgolfclub.com to purchase or contact the Pro Shop at 520-825-3110. Our new rates for daily play and memberships are now available online. Here are some benefits of becoming an annual member. 18-hole memberships receive 9-day advance tee times and 8-day advance for 9- hole memberships. Unlimited driving range privileges. Receive 25% off Pro Shop apparel and 10% off accessories, equipment, shoes, hats, and golf balls (excluding sale items). -

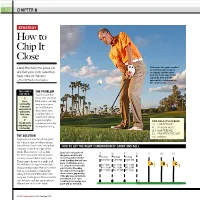

How to Chip It Close

126 CHAPTER 6 STRATEGY How to Chip It Close Land the ball one pace on Determine the yards needed to land the ball one pace and let your club selection on (carry), and the yards from the front edge to the take care of the rest cup (roll), then pull the —Top 100 Teacher Scott Sackett appropriate club based on the chart below. THIS STORY IS THE PROBLEM FOR YOU IF... You’re aware that 1 every chip shot you You’re hit features varying confused by amounts of carry how much and roll, but you carry and roll you need to don’t know how land chips to select clubs or close. adjust your swing 2 to get the right Club Guide (Carry:Roll) You hit every combination for the <1:1 LOB WEDGE chip with your shot you’re facing. sand wedge. 1:1 SAND WEDGE 1:1.5 GAP WEDGE 1:2 PITCHING WEDGE THE SOLUTION >1:2 9-IRON Regardless of how far off the green the ball is sitting, or where the pin is positioned, try to land every chip HOW TO GET THE RIGHT COMBINATION OF CARRY AND ROLL one pace on the front edge of the green. That gives you a baseline Say you’re 10 yards off 15 10 5 0 5 10 15 for determining the exact amount the green, and the pin of carry versus roll for every shot. is cut 10 yards from the TO FLAG TO FLAG TO FLAG (Carry: Roll) (Carry: Roll) (Carry: Roll) Then, using the guide at right, pull front. -

$75,000 in CASH & PRIZES*

$75,000 in CASH & PRIZES* st th August 31 – Sept. 4 , 2011 Wednesday, Aug.31st - Charity Pro-am 2010 Van Open Champion: Adam Hadwin Fraserview Golf Course – 1pm Shotgun Thursday, Sept.1st - Practice Rounds (Details on practice round rates TBA) Friday, Sept.2nd - Round One McCleery Golf Course – 7:30 am Start Professionals and Championship Amateurs Langara Golf Course – 7:30 am Start Flight A and B Amateurs Saturday, Sept.3rd - Round Two Langara Golf Course – 7:30am Start Professionals and Championship Amateurs The 54-Hole Championship includes: McCleery Golf Course – 7:30 am Start Flight A and B Amateurs Great tee-gift; Buffet lunch each day you compete th Guaranteed 36 holes of golf (18 holes at McCleery Sunday, Sept.4 - Final Round and 18 holes at Langara). Fraserview Golf Course – 7:30am Start Live Leaderboard screens on course Driving range warm-up at McCleery and 36-Hole Cut: Fraserview Professionals: Top 60% and ties make the 36-hole cut Fantastic Prize table for top gross and net scores Amateurs: Top 60% and ties in each Amateur Flight (Gross scores in Championship; Net scores in Flight A 2010 Amateur Champion: Kris Yardley (L) and B) make the cut to play the final round. Eligibility Open to Pros & Amateurs with RCGA Factor 18.0 or less. Full Field: 224 golfers (100 pros; 124 amateurs). Pro Purse: $50,000* 1st Place: $10,000* *Based on Full Field Championship Entry Fees Professionals: VGT Preferred Members: $350 + tax CPGA/Can Tour Members: $400 + tax Non-VGT/CPGA/Can Tour: $500 + tax Amateurs: VGT Preferred Members: $225 + tax Spectator Tickets: VGT Basic or Non-Members: $275 + tax $10/per day or $20 for full week pass. -

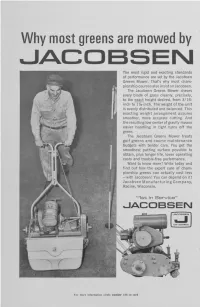

Why Most Greens Are Mowed By

Why most greens are mowed by The most rigid and exacting standards of performance are set by the Jacobsen Greens Mower. That's why most cham- pionship courses also insist on Jacobsen. The Jacobsen Greens Mower shears every blade of grass cleanly, precisely, to the exact height desired, from 3/16- inch to lVs-inch. The weight of the unit is evenly distributed and balanced. This exacting weight arrangement assures smoother, more accurate cutting. And the resulting low center of gravity means easier handling in tight turns off the green. The Jacobsen Greens Mower treats golf greens and course maintenance budgets with tender care. You get the smoothest putting surface possible to obtain, plus longer life, lower operating costs and trouble-free performance. Want to know more? Write today and find out how the expert care of cham- pionship greens can actually cost less —with Jacobsen! You can depend on it! Jacobsen Manufacturing Company, Racine, Wisconsin. "1st in Service" JACOBSEN Spray time-proven Tersan OM and be sure Du Pont "Tersan" OM* turf fungicide applied late in the fall will prevent snow mold from developing in late winter and/or early spring. • "Tersan" OM, a mercurial-organic sulphur combination prevents snow mold and other major turf diseases. • Thoroughly tested..."provides long-term residual protection. • Large safety factor under all conditions. • Disease prevention is obtained with an application of 8 ozs. of "Tersan" OM per 1000 sq. ft. as late as possible prior to snowfall. Follow with 3 ozs. per 1000 sq. ft. in early spring during freezing and thawing. For full information on "Tersan" OM and other dependable Du Pont Turf Products, consult your golf course supplier...your service agency. -

2200 Year Old Mathematical Theory Combines with Space Age Computer ® Design and CNC Manufacturing to Produce the Putting Arc

2200 year old mathematical theory combines with space age computer ® design and CNC manufacturing to produce The Putting Arc . Now you can feel, see and learn the Perfect Putting Stroke. Learn the 'arc type' stroke used by the vast majority of the modern day touring pros. For a 'Quick Start' and simple instructions, go to the back page. The Putting Arc works because… 1. It is based on a natural body movement which can be quickly learned and repeated. Results can be seen in several days ... thousands of repetitions are not required. 2. The clubhead travels in a perfect circle of radius R, on an inclined plane. The projection (or shadow) of this circle on the ground is a curved line called an ellipse, and this is the curve found on The Putting Arc . 3. The putter is always on plane (the sweet spot/spinal pivot plane). The intersection of this plane with the ground is a straight line, the ball/target line. (See Iron Archie - page 11) 4. The clubface is always square to the above plane. It is only square to the ball/target line at the center line on The Putting Arc . You are learning an inside to square to inside putting stroke. (See Iron Archie - page 11) 5. The lines on the top of The Putting Arc show the correct club face angle throughout the stroke, including a square initial alignment. This concept is as important as the arc itself , and it is a patented feature of The Putting Arc . 6. In this perfect putting stroke, there is only one moving part. -

Titleist Introduces New Scotty Cameron Phantom X Putters

⏲ 10 February 2021, 09:49 (GMT) Titleist Introduces New Scotty Cameron Phantom X Putters Updated Tour-Inspired Designs and New Models Strengthen Mallet Family FAIRHAVEN, Mass. (Feb. 9, 2021) – Drawing on his extensive experience with golf’s greatest players, Scotty Cameron has bolstered the high-tech Phantom X family with four new tour- inspired setups. The updated Phantom X 5 and Phantom X 5.5 replace current in-line models, while the new Phantom X 11 and Phantom X 11.5 - compact wingback mallets - add new options engineered for performance. Available March 26 in golf shops worldwide, the new Phantom X putters are inspired by the designs that Master Putter Maker Scotty Cameron has crafted for tour players around the globe. All four putters feature solid stainless steel faces and bodies with new shapes and neck configurations. The Phantom X 5 and Phantom X 5.5 models have been completely revamped and replace the current putters as a rolling change. The new Phantom X 11 and Phantom X 11.5 were developed based on player requests for a slightly smaller setup in the spirit of the Phantom X 12 and 12.5 models. QUOTING SCOTTY CAMERON “Working with our game’s best players gives me great perspective into what they are looking for in a mallet putter. From the types of metals used to the subtle changes in shaft bends, these new Phantom X models offer brand new, highly requested options that build on our most popular models from 2020. I’ve had so many people asking for a putter like Justin Thomas’ gamer – and the Phantom X 5.5 is my direct answer. -

One Man's Quest to Stay Dry and Comfortable in the Wettest Conditions

by Scott McCredie photos by Gregg Bleakney SINGIN’’d always been a fair-weather cyclist, we loaded up our bikes with test gear — IN THE RAINremained on the inside. At most, I’d felt but living in the Pacific Northwest including rain-ready bicycles, panniers, only a sheen of moisture along the shoul- meant I could only ride for five lights, and outerwear — for an overnight ders of the Gore jacket, after a particularly months of the year. What would it tour of the southern shore of the mighty rigorous Seattle hill ride. Itake, I wondered, to extend my riding Quinault. Call it a dry run. It seemed to me that eVent might have season into the monsoon season? Was it The Olympics, however, were just one been a little drier than Gore-tex, but I want- possible to be comfortable riding in the of the proving grounds for rain testing that ed more scientific evidence. So I delved rain and wind without having to pump out took place over several months in 2009. into research the U.S. Army has done in a a gazillion kilocalories of muscular effort to I took several wet-weather rides around quest for the best rainwear for soldiers. Its stay warm? Could cycling in a downpour Washington, including a week-long spring conclusion was that eVent beats Gore-tex in ever be fun — or at least pleasant? The tour from Seattle to the coast. Here’s what the breathability department. But what did only way to find out was to go out and test I learned… that really mean? cycling gear designed to do just that. -

Golf Glossary by John Gunby

Golf Glossary by John Gunby GENERAL GOLF TERMS: Golf: A game. Golf Course: A place to play a game of golf. Golfer,player: Look in the mirror. Caddie: A person who assists the player with additional responsibilities such as yardage information, cleaning the clubs, carrying the bag, tending the pin, etc. These young men & women have respect for themselves, the players and the game of golf. They provide a service that dates back to 1500’s and is integral to golf. Esteem: What you think of yourself. If you are a golfer, think very highly of yourself. Humor: A state of mind in which there is no awareness of self. Failure: By your definition Success: By your definition Greens fee: The charge (fee) to play a golf course (the greens)-not “green fees”. Always too much, but always worth it. Greenskeeper: The person or persons responsible for maintaining the golf course Starting time (tee time): A reservation for play. Arrive at least 20 minutes before your tee time. The tee time you get is the time when you’re supposed to be hitting your first shot off the first tee. Golf Course Ambassador (Ranger): A person who rides around the golf course and has the responsibility to make sure everyone has fun and keep the pace of play appropriate. Scorecard: This is the form you fill out to count up your shots. Even if you don’t want to keep score, the cards usually have some good information about each hole (Length, diagrams, etc.). And don’t forget those little pencils. -

2007 Catalog

CLUB SPECIFICATIONS COBRA GOLF 1818 ASTON AVENUE CARLSBAD CA 92008 1.800.917.3300 WWW.COBRAGOLF.COM © 2007 Acushnet Company. Acushnet Co. is an operating company of Fortune Brands, Inc. NYSE: FO. Graphite Design, Golf Pride, Winn Grip, Fujikura Vista, True Temper, Aldila, AccuSport Speed Monitor, Nippon and Mitsubishi Rayon are trademarks of Graphite Design International, Inc., Eaton Corporation, Winn Inc., Fujikura Rubber Ltd., True Temper Sports Technologies, Aldila Inc., AccuSport International, Inc., Nippon Shaft Company, Ltd., and Mitsubishi Rayon Company, Ltd., respectively. 1 // Cobra® Product Guide 2007 Club Specifications // 2 KING COBRA SPEED LD DRIVERS // Men’s Specifications KING COBRA SPEED LD FAIRWAY METALS // Seniors’ Specifications SPEED LD/F SPEED LD/M OFFSET SENIORS’ HEAD MATERIAL: 6-4 Titanium with Milled Dual-Rhombus Face Insert HEAD MATERIAL: 17-4 Steel with Face Insert GRIP: Cobra Speed/Golf Pride Tour Velvet 50D Durometer SHAFT: Cobra/Aldila NV-F, 55g GRIP: Cobra Speed/Golf Pride Tour Velvet 45D Durometer SHAFT: Cobra/Mitsubishi Bassara, 45g Loft Head Size/Face Angle Length Lie Swing Weight Shaft Weight Stock Flex RH/LH Model Loft Head Size Length Lie Swing Weight Shaft Weight Stock Flex RH/LH 9.0º 460cc/2.0º Slight Draw 45.00'' 59.0º D3 55g R, S RH/LH 3 18.0º 159cc 43.00'' 57.0º D0 45g Lite RH/LH 10.5º 460cc/2.0º Slight Draw 45.00'' 59.0º D3 55g R, S RH/LH 5 21.0º 149cc 42.50'' 58.0º D0 45g Lite RH/LH 7 24.0º 139cc 42.00'' 59.0º D0 45g Lite RH/LH SPEED LD/M STRAIGHT NECK 9 27.0º 130cc 41.50'' 59.0º D0 45g Lite -

C:\Documents and Settings\Owner

2 / AMERICAN ANTIQUITIES JOURNAL Volume 28, Spring/Summer 2021 AMERICAN ANTIQUITIES JOURNAL Volume 28, Spring/Summer / 3 Enjoy your next road trip to one of our 500+ client cities. Let this be your guide for AboutAbout thethe CoCovverer shopping, dining, lodging, recreation, entertainment & historic points of interest for the AMERICAN HERITAGE TOURIST www.AmericanAntiquities.com The history of sports in sport and protection, and it America shows that Ameri- was believed that knocking can football, indoor American down these kegels, or pins, football, baseball, softball, with a rock would pardon and indoor soccer evolved out their sins. of older British (Rugby foot- Golf’s history in the U.S. ball, British baseball, Round- dates to at least 1657, when ers, and association football) two drunk men were arrested sports. American football and for breaking windows by baseball differed greatly from hitting balls with their clubs the European sports from in Albany, New York. which they arose. Baseball However, no real traction was has achieved international gained until the early 19th popularity, particularly in century. In 1894 the United East Asia and Latin America, States Golf Association was while American football is formed to become exactly that, American Football. ambassadors for the game in Lacrosse and surfing arose the states, which by 1910 was from Native American and host to 267 golf clubs. Native Hawaiian activities Fishing is an important part that predate Western contact. of American history. It helped Horse racing remained the people survive long before the leading sport in the 1780-1860 United States was ever formed. era, especially in the South. -

Slice Proof Swing Tony Finau Take the Flagstick Out! Hot List Golf Balls

VOLUME 4 | ISSUE 1 MAY 2019 `150 THINK YOUNG | PLAY HARD PUBLISHED BY SLICE PROOF SWING TONY FINAU TAKE THE FLAGSTICK OUT! HOT LIST GOLF BALLS TIGER’S SPECIAL HERO TRIUMPH INDIAN GREATEST COMEBACK STORY OPEN Exclusive Official Media Partner RNI NO. HARENG/2016/66983 NO. RNI Cover.indd 1 4/23/2019 2:17:43 PM Roush AD.indd 5 4/23/2019 4:43:16 PM Mercedes DS.indd All Pages 4/23/2019 4:45:21 PM Mercedes DS.indd All Pages 4/23/2019 4:45:21 PM how to play. what to play. where to play. Contents 05/19 l ArgentinA l AustrAliA l Chile l ChinA l CzeCh republiC l FinlAnd l FrAnCe l hong Kong l IndIa l indonesiA l irelAnd l KoreA l MAlAysiA l MexiCo l Middle eAst l portugAl l russiA l south AFriCA l spAin l sweden l tAiwAn l thAilAnd l usA 30 46 India Digest Newsmakers 70 18 Ajeetesh Sandhu second in Bangladesh 20 Strong Show By Indians At Qatar Senior Open 50 Chinese Golf On The Rise And Yes Don’t Forget The 22 Celebration of Women’s Golf Day on June 4 Coconuts 54 Els names Choi, 24 Indian Juniors Bring Immelman, Weir as Laurels in Thailand captain’s assistants for 2019 Presidents Cup 26 Club Round-Up Updates from courses across India Features 28 Business Of Golf Industry Updates 56 Spieth’s Nip-Spinner How to get up and down the spicy way. 30 Tournament Report 82 Take the Flagstick Out! Hero Indian Open 2019 by jordan spieth Play Your Best We tested it: Here’s why putting with the pin in 60 Leadbetter’s Laser Irons 75 One Golfer, Three Drives hurts more than it helps.